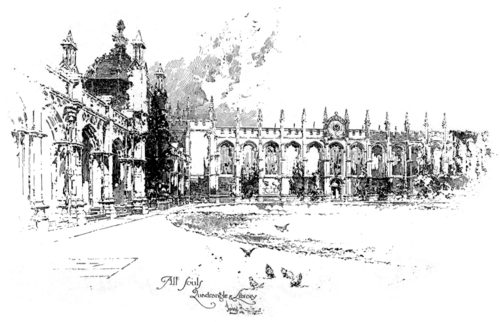

ALL SOULS

The full name of "All Souls" is "The College of the Souls of All the Faithful Persons Deceased in Oxford," It was founded in 1437, as a Memorial to the Brave Warriors who fell at Agincourt in 1415; and it thereby antedates the discovery of America by over half a century.

It took seven years to complete the buildings, at a cost of a little over four thousand pounds. The account-books, which have been preserved, make very pleasant reading to those of us who have, in recent days, been paying for the erection of private homes, or of public institutions, in the New World. The workmen were the most skilful that could be procured; and we learn that sawyers and carpenters were paid sixpence a day; masons eight pence; laborers four pence half penny; daubers—otherwise painters—five pence, and all female laborers five pence. A horse, purchased for the Warden, in 1451, cost sixty shillings; a pair of boots two and eight pence; and,most interesting of all, the bill for a small pig and a capon—it is not recorded for whose consumption—amounted to twelve pence—say a quarter of a dollar—for the pair.

All Souls, despite its comparative antiquity and its annual income now of eighteen thousand and eighty-six pounds sterling, is not particularly rich in Literary Associations. Linacre, Jeremy Taylor, Sir Christopher Wren, Edward Young, Blackstone and Heber may be counted among its Fellows; but its Undergraduates, and Graduates, seem to have left very few Landmarks on the Road of Letters.

It is not an easy matter, even for the Oxford man himself, to say exactly what a Fellow is. There are, in Oxford, all sorts of Fellows. Good Fellows, Bad Fellows, Odd Fellows, and just plain Fellows. "The Century Dictionary" thus defines him: "In England [a Fellow is] a graduate member of a college, who shares its revenues."

The Oxford Fellow differs in different times and in the different colleges. He is elected; he is appointed. He must be a single man; he may marry a wife. He must be in residence; he may board and lodge wherever he sees fit. He cannot leave Oxford; he need not remain in Oxford. He may be a Tutor, a Lecturer, a Professor; he may be a Fellow and nothing more. He must be a Graduate of the college in which he holds his Fellowship; he may be a Graduate of one college and a Fellow of another. He may be an Honorary Fellow, with no Oxford degree at all. But he must, in most cases, have taken at least the degree of Bachelor of Arts, or of a Student in the Civil Law, from some College or University. His income from his college varies from thirty to two hundred and fifty pounds a year. And he is bound to be a gentleman and a scholar, with certain duties, privileges, and responsibilities; and not a little unusual amount of learning.

Thomas Linacre, Physician and Classical Scholar, is supposed to have been sent to Oxford as a student in his twentieth year; but it is not known to what college, if to any college. He became a Fellow of All Souls in 1484; and Anthony Wood asserts that he was a Lecturer there about the year 1510. One of his favorite pupils was Erasmus, with whom, however, he quarrelled over a Latin Grammar, which was prepared by Linacre for St. Paul's School, but was not satisfactory, in all respects, to the heads of that institution. It is impossible now, of course, to estimate Linacre's skill and powers as a physician; but Erasmus declared that his Latin translations of Galen and Aristotle had a grace of style which was hardly equalled in the original Greek.

Erasmus went to Oxford, according to Anthony Wood, in 1497, and remained until 1499; learning Latin, in Oxford, according to one of his Oxford detractors, in order to teach it in Cambridge. He is said to have lodged in Frewen Hall, only a small portion of which is left. Its entrance is a pretty little gateway, at the end of Frewen Court, a narrow passage on the west side of the present Cornmarket Street, running towards New Inn Hall Street, and just beyond the house of the Union Society. Frewen Hall is known now only as the Oxford residence, during his undergraduate life, of Albert Edward, Prince of Wales, a student who will soon be entirely forgotten, except as a King of Great Britain; while Erasmus, concerning whom Oxford knows and cares almost nothing, will live almost forever.

In his "Praise of Folly" Erasmus speaks of the Grammar Teachers of the Middle Ages, particularly in Oxford, as a "race of men the most miserable, who grow old in penury and filth in their schools (—schools did I say? prisons, dungeons! I should have said) among their boys, deafened with din, poisoned by a fetid atmosphere; but, thanks to their folly, perfectly self-satisfied, so long as they can bawl and shout to their terrified boys, and box, and beat, and flog them; and so indulge, in all kinds of ways, their cruel dispositions." Thus, in the days of Erasmus, was the twig bent, and applied, in the formation of the common mind.

Jeremy Taylor was a native, and a student, of

Cambridge. In 1636 he was made a Perpetual Fellow of All Souls, where, it is said, he studied books rather than men, and was apt to slight, much too much, the arguments of those with whom he discussed. Nevertheless one of his contemporaries and admirers declared that "he had the good humor of a gentleman; the eloquence of an orator; the fancy of a poet; the acuteness of a school-man; the profoundness of a philosopher; the wisdom of a chancellor; the sagacity of a prophet; the reason of an angel, and the piety of a saint." Which leaves very little more to be said in favor of Jeremy Taylor.

Sir Christopher Wren, a graduate of Wadham, became a Fellow of All Souls in 1653; enriching the latter college, as he enriched everything he touched, by building a great sun-dial, still to be seen, and consulted, in the Back Quadrangle, and by bequeathing to the Library a collection of his own architectural drawings, which are now almost beyond price. The dial, which bears, in Latin, a motto explaining that "The Hours pass away, and are counted against us," was, and is, so reliable that it has set the time, during many generations, for all the clock-makers, and watch-makers, and time-keepers of Oxford.

Edward Young was appointed to a Law Fellowship of All Souls in 1708, where he is supposed to have been already distinguished for superior learning. He had been a student at New College, and at Corpus Christi.

William Blackstone, the famous and almost immortal Commentator, was educated at Pembroke; but he became a Fellow of All Souls in 1744, and Professor of Common Law in 1758.

He is described as possessing a curious combination of physical sloth and mental irritability. Boswell says that he wrote the "Commentaries" with a bottle of port wine before him, "being invigorated and supported in the fatigue of his great work by the moderate use of it." He was ever ready to confess, and to regret, his bad temper; but he never overcame his dislike for any sort of bodily exercise; and he seems to have died, literally, from the lack of it. He was too lazy to take the trouble to live. This is a solemn warning against even the moderate use of port wine, in cases of great works!

These Commentaries of Blackstone, by the way, were first uttered in the form of Lectures, to the students of All Souls; and they thus established a pleasant precedent to this present writer, whose words originally spoken, were intended, later, to find a larger market in print.

Blackstone, inspired, no doubt, by his temperate use of port wine, is said, also, to have established

another precedent, perhaps as pleasant, but not perhaps so wholesome as lecturing future works. He introduced the corkscrew into college-life in Oxford; and he set the example of the establishment of college wine-cellars, and the natural abolishment of the obnoxious habit of running to the tavern, across the road, for a poorer, and more harmful, grade of sherry or sack. Remains of an old tavern, across the road, in the High Street, exceedingly rich in old oak carvings and hewn beams, are still extant, and are well worth careful study. But there are at present opposite All Souls in the High Street no actual public-houses which date back to the period of Blackstone's great reformation; although The Mitre, in High Street, is not many steps away. With The Mitre the contemporary Oxford undergraduate is not altogether unfamiliar, despite the solemn fact that the statutes demand of him to refrain from all taverns, wineshops, and houses in which they sell wine, or any other drink, and the herb called nicotina or tobacco.

It may be mentioned that in the History of Lincoln we read how, in 1488, by an agreement with Margaret Parker, widow of William Dagville, that college came into possession of considerable property in Oxford, including Dagville's Inn [now The Mitre] in High Street, which was already an ancient inn when Dagville inherited it, about the year 1450. This gives The Mitre no small claims to a ripe old age, and shows that it has been familiar to a great many generations of students.

Reginald Heber became a Fellow of All Souls in 1805; but he was afterward more intimately associated with Brazenose, his Alma Mater.

The following letter sounds very much like a piece of contemporary American prose. It is addressed to the Undergraduates of All Souls, and it says: "The Feast of Christmas drawing now to an end, doth put one in mind of the great outrage which, as I am informed, was last year committed in your College, where although matters had formerly been conducted with some distemper, yet men did never before break into such intolerable liberty as to tear down doors and gates, and disquiet their neighbors, as if it had been a camp, or a town in war." This letter was not written, at the end of the Nineteenth or at the beginning of the Twentieth Century, by President Patton or President Wilson of Princeton, by President Eliot of Harvard, or by President Hadley of Yale; it was written, early in the Seventeenth Century, by Archbishop Abbott, who was then acting in a position somewhat like to that of our Overseers or Trustees; and thus doth history repeat itself! The great outrage referred to was not the distemper natural to the winning of some occasional champion ball game, when furniture smashes itself, and benches and fences get themselves burned up, of their own accord! But it was the annual, formal, pretended search, at midnight, with torches, by the students, for their tutelary bird, a mallard duck, which, according to tradition, sprang out of a drain when the first stone of the original college building was laid.

They hunted for their duck in this distempered manner, it is said, for three or four hundred years; and one irreverent historian of Oxford, who was rash enough to insinuate that this highly honored bird was not a huge and classic drake, but a middle-sized, common, barn-yard goose, was pelted with pamphlets by all All Souls for his pains.

Many and various are the titles given in Oxford to the Rulers of the Colleges. The Warden of All Souls, for instance, would be the Master of Balliol, the Dean of Christ Church, the Provost of Oriel, the President of Trinity, the Rector of Lincoln, and the Principal of Jesus. And if one of the American College Presidents had been—and, happily for the Americans, he is not—the Rector of Brazenose, the Warden of Wadham, or the Provost of Queen's, the perplexed citizens of the United States would be guilty of a gross breach of social collegiate etiquette if they addressed him as "Mr. President."