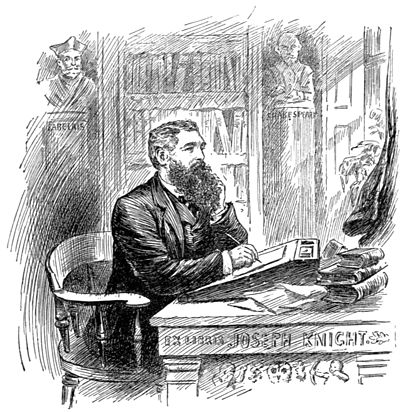

JOSEPH KNIGHT.

His father and mother.Joseph Knight was born on the 24th of May, 1829, at Leeds, where his father was in business as a cloth merchant. His brother John describes the father as being one of the most handsome men he has ever seen, and both sons "worshipped him, for his beautiful life fell in no wise short of his beautiful face, and we never heard from him a shady or ungracious word." The mother also was handsome and a charming woman; but at the early age of thirty-nine she lost her sight, and remained blind all her life. Notwithstanding her terrible affliction, she was one of the brightest and happiest of women, and lived to the age of seventy-three. Joseph Knight inherited from her his high social qualities, and his early life is described by his brother as being "very interesting and distinctly high-souled"; he was a student and an inveterate reader, his special favourite being poetry.

His education.He received his education at a very popular North-Country school, Bramham College, near Tadcaster. With Knight were some 150 boarders. The school buildings and master's residence a fine old Hall were of considerable importance, and the surrounding scenery was singularly beautiful. The head of the school, Dr. Haigh, was a great linguist, being master of twenty-two languages, and a born schoolmaster, both honoured and feared by the boys. He was most enthusiastic in his teaching, and had a great belief in training the memory, requiring every boy to learn poetry and to stand up and declaim it before the whole school. One year he offered a prize of £5 to the boy who at one effort repeated the most lines. This caused great excitement in the school, and expectation soon centred on two youths, these being a boy named Wilson, from Sheffield, and Joe Knight. Wilson started off with eight hundred lines of 'The Lady of the Lake,' ending with a torrent of applause. Knight followed with 'Paradise Lost,' and when he had completed the first book without a stumble, and was complacently starting on the second, Dr. Haigh cried "Enough!" and awarded him the prize.

Dr. Haigh, believing in the possibility that "some mute inglorious Milton here may rest" under the shadow of the College walls, required each boy to compose weekly a minimum of eight lines of original poetry, good, bad, or indifferent; and when a poem of exceptional ability presented itself, he would have it printed hi dainty form and distributed among the boys' parents. Knight secured this honour by composing the following poem, of which a few copies were printed by J. H. Greaves, Snig Hill, Sheffield, 1848. It is now hardly obtainable.

THE SEA BY MOONLIGHT.

His first printed poem.

The setting sun had sunk beneath the tide,

And, glittering in her starry diadem,

The silver crescent, like an Eastern bride,

As fair, as pure, as the bright diamond gem,

Unveiled her lovely head; the billows hem,

With glittering spray and foam, the rocky shore,

Whose beetling crags the gathering waters stem,

Which, fretting, break with wild tumultuous roar,

While towards the azure Heavens their crested summits soar.

Hark! o'er the moonlit waters borne along—

Now loud, now soft, as swells or dies the gale—

Rises some lone advent'rer's distant song,

Blending with the hoarse sea-birds' dismal wail,

Singing, as 'neath the moonbeams glistening pale,

His little skiff dances along the sea,

The scattered spray kissing her snowy sail,

The waters' wide waste heaving on her lee,

While the young Rover sings, exulting, careless, free.

And now she nears the shore: upon the prow,

With youth elate, the daring sailor stands;

Fair hope sits laughing on his open brow;

He grasps her cable in his manly hands,

He feels her keel graze on the shelving sands;

A moment more, and from the deck he springs,

And on the yielding beach in safety lands;

Then his frail bark far on the shore he brings,

And, to beguile his task, still cheerfully he sings.

But now his strain in distance dies away;

All human sounds have ceased, and peaceful sleep

Enwraps the smiling scene, save where, in play,

The calmed billows of the surging deep

Responsive whisper to the winds, that sweep

Along the sea, or in the briny tide

The hoarse sea-mews their glossy plumage steep,

And, gaily sporting, onward now they glide,

Like a swift arrow's flight across the waters wide.

Can there be one whose spirit will not melt,

Listening to the waves' wild harmony?

Nor feel a charm he n'er before has felt—

A wild ecstatic pleasure through him fly—

Thrill every nerve, and chain his wondering eye

Unto the spot, and, gazing on this scene,

Viewing the placid ocean rearing high

Her billowy breast, unmoved the waves has seen

Foam on the sea-girt coast, and scatter wide their sheen?

See, from yon lofty promontory's brow,

The beacon's pale light flickers o'er the main,

And strews the hidden rocks that lie below;

Where many a noble bark, which strove in vain

The adjacent harbour's shelter safe to gain,

Has sunk, alas! upon the treacherous shore!

And many a gallant sailor's corse has lain

Within thy blue waves, mid the water's roar,

Or, by thy rough waves tost, lies blackening on the shore.

But now the blustering winds are hushed in peace;

No storms disturb the calm and tranquil deep;

The hoarsely roaring billows' murmurs cease,

And shrouded seems the ocean now in sleep,

The brine is dripping from each craggy steep;

Silence unbroken reigns; not e'en a gull

Does o'er the heaving waves her swift course keep;

Still the moon's beams the enraptured spirit lull,

Ne'er could be ought on earth more wild, more beautiful.

"King of the College."Dr. Haigh, with all his scholarship, was quite unable to speak in public. This had been a source of great humiliation to him, and he determined that the boys in his school should, if possible, be saved from this disadvantage. To this end he instituted a yearly election of a "King of the College." On a certain day the boys were invited to write on a slip of paper the name of the candidate they voted for, and each boy had to return thanks for the number of votes he had received. Knight secured the 25 votes necessary to become a successful candidate, and there were two others, one being a son of George Leeman, M.P. for York and Chairman of the North-Eastern Railway. After the nomination the candidates each selected six speakers, and both candidates and speakers had a week's holiday to prepare for the great day of election. Hustings were erected in front of the College. A distinguished "old scholar" was invited to act as sheriff. Parents and friends were present, and the neighbouring gentry were invited. The grounds were crowded, and open house kept. Each candidate had his own special colours, with banners and scarves, the former being of silk with richly painted designs. Knight's father expended £30 on his son's show. Mr. Knight informs me that his brother won the election, and became "King of the College." He had as a boy at school the charming manners he preserved all through life, and was universally esteemed. At this time Mr. Stephen Wilson, one of the masters of the College, made the pen-and-ink sketch of which I have obtained a copy from the original, lent me by Mrs. Knight for the purpose. Wilson was greatly attached to Knight, was beloved by every boy in the school.

Knight's father wished that on leaving school he should remain with him and learn the cloth trade. For a time he acceded to this, although it was distasteful to him. His health was far from good, and was a cause of much anxiety for many years, and when he first came to London it was anticipated that his life would be but short. His health being so precarious, his father allowed him much freedom, and he devoted all the time he could to acquiring knowledge. This he did to a marvellous extent, and those who knew him in after life, with his wide range of learning, would never imagine that he received only a few years' schooling as a boy.

The Counter ReformationWhen about eighteen, Knight, along with other bright young fellows, including the present Poet Laureate, and notably Edward Hewitt, founded a Mechanics' Institute in Leeds. This was financially aided by a fine old member of the Society of Friends, Mr. Pease, a member of the Pease family of Darlington. The young men delivered lectures at the Institute. "My brother," writes Mr. Knight, "gave one on 'The Counter Reformation,' and much amusement was caused by the shopkeepers and their customers flocking to it, expecting to hear of shortened shop hours and improvements in the construction of their shop counters."

Hewitt gave a scientific lecture with illustrations, and borrowed apparatus from the Leeds Philosophical Hall. Mr. Pease was in the chair. Hewitt was in the act of emptying the air-pump when it exploded with a terrific report, and Mr. Pease was discovered flat on his back on the floor. Fortunately he was unhurt, but he naturally took the precaution not to occupy the chair again, and seated himself far away from the table where the lecturer was performing his experiments.

'THE FAIRIES OF ENGLISH POETRY.'

'The Fairies of English Poetry.'Among lectures delivered by Knight at this time was one on 'The Fairies of English Poetry,' before the Leeds Philosophical and Literary Society, of which he was the President, on the 7th of April, 1854. The original MS. of this, beautifully written, was purchased by his nephew Mr. A. Langford Knight, who has kindly lent it to me. From beginning to end it shows the patient care and research which characterized all Knight's work. It opens thus:—

"That man's mind is essentially superstitious is the natural and inevitable result of the circumstances in which he finds himself placed. . . . He knows not who or what he is, has been, or shall be, whence comes he, and where he goes. . . . These are questions which must always be recurring to his mind, and with which all his boasted science and 'nice' philosophy will be unable to grapple. Our religion itself, while it informs him of all that is necessary to fit him for that world to which he hastens, yet leaves him purposely ignorant of its nature and of that of its inhabitants. Thus situated, who can marvel that man has peopled this unknown universe with his own ideal conceptions? Upon the shapes and attributes of these imaginary denizens of 'that undiscovered country' the countless generations of mankind have lavished all the treasures of their imagination."

He claims that the true home of the fairy is England, for its lovely scenery and its wide moors, so bountifully covered with the rich heath bells, "have always attracted these charming and unearthly little creatures, so generous in their friendships, and yet so capricious, so implacable in their resentments against whoso shall break in upon" their concealed solemnity. After turning aside to give a little word-lore, Knight refers to "the beautiful romance of Orfeo and Heurodis" as being a great curiosity in fairy literature, "one of the most beautiful of the Fairy Romances we possess," and "analyzed by Scott in the second volume of his 'Border Minstrelsy,'" in which he gives it as an instance of "Gothic mythology engrafted on the fables of Greece."

The paper shows a most ultimate knowledge of Chaucer, Shakespeare, Herrick, and Spenser. With Spenser Knight is angry, for he "indeed calls his poem 'The Faerie Queen,' and talks about the land of Faerie; but as far as regards any reference it contains to the 'good folk,' he might as well have called it 'The Queen of Tahite' or 'Queen Dido.' Throughout the whole of Spenser's great poem there are but two incidental allusions to the popular attributes of the Faeries. . . . Spenser's account of the origin and genealogy of his Faeries is totally different from anything we meet with in any other work, prose or poetical, on the subject. He seems in its formation to have drawn as largely upon the rich and varied stores of his imagination as he has in any of the marvellous adventures with which his enchanting work is stored. He seems to have studiously put on one side all that his predecessors had said or sung concerning them, and to have given them an origin and pedigree of his own, and one which should enable him to adhere consistently to one of the (we are sorry to record it) main objects of his poem that of paying a long and elaborate compliment to that most beflattered of all women, Queen Elizabeth."

Knight complains of the neglect of Drayton, who is "now only known to the student of early English literature, or the antiquary," but who "has done most after Shakespeare to secure to the Faeries an immortality of beauty." After making reference to "many beautiful allusions scattered through his works," Knight calls special attention to his poem entitled 'Nymphidia; or, The Court of the Fairy,' in which "a high degree of poetical merit is blended with a lively style and wit, and a playful turn of fancy almost Shakespearian."

At Leeds Knight's ready wit and powers of conversation gained him hosts of friends. Some of these would frequently meet and dine together, when all the evening the wit would sparkle across the walnuts and the wine. Chief among the houses where the friends met was that of Edward Hewitt at Headingley. Hewitt's only brother William was the dearest friend of my youth. Edward Hewitt and the Prince Consort.Edward Hewitt, like Knight, was a man of very handsome presence, and was thought a great deal of in Leeds, being chosen to show Prince Albert the cloth exhibits on the occasion of the Queen's visit to open the new Town Hall in 1858. The Prince was so well informed that Hewitt, with his comparatively limited technical knowledge, found many of the questions the Prince put to him regular "posers."

The wits included George William Conder, Minister of Belgrave Chapel, Leeds, where the Knight family attended. Among the wives of the wits was a lady who was very proud of her plate, and was always assuring her friends that it was "solid silver." Knight, ever keen for a joke, would frequently pretend to admire some special article for the fun of hearing the emphatic way in which she would assure him that "it is solid silver." We have often laughed together over this.

W. E. Forster. While at Leeds he formed a great friendship for W. E. Forster, and when Forster made his first attempt to enter Parliament, he contested Leeds, Knight seconding his nomination. During the contest Forster resided at Knight's house. Marquis of Ripon.The present Marquis of Ripon, then Lord Goderich, was another friend who stayed with him, drawn there by the fine library of books that even then, so early in his life, Knight had got together. Lord Goderich became a member of the Leeds Club on Knight's nomination.

Knight's uncle, James Young Knight, and his family were also living at Leeds at this time. James's only son, John C. Knight, and Joseph and his brother were greatly attached to one another, being, indeed, more like brothers than cousins. John was a "man of great culture, a good classic," and, Mr. Knight tells me, "one of the most interesting conversationalists I ever knew, save and excepting my brother." The father was a deacon at East Parade Chapel, and Dr. Reynolds, when he became its minister in 1849, formed a very close friendship both with father and son. In the life of Dr. Reynolds, published by Hodder & Stoughton, eighteen letters from John C. Knight and his wife are inserted; and it is stated that "both were his valued friends, and from the heart and mind of the younger man he derived stimulus, support, and consolation." John C. Knight in one letter to Reynolds writes: "No one ever made holiness so lovely, hope so bright, faith so much like sight, as you" (p. 130).

Knight's marriageOn the 3rd of June, 1856, Knight was married at the Parish Church, Leeds, to Rachel, younger daughter of John Wilkinson, of Gledhow Mount, near Leeds. He remained at Leeds until 1860, when he left for London. Although then just over thirty, he came full of the assurance of youth, and he often laughingly told his friend Mr. W. L. Courtney that he then "felt capable of either editing The Times or commanding the Channel Fleet." However, it was not long before he was "found out," and he almost at once began writing for The Literary Gazette, then under the direction of John Morley.

J. A. Heraud.Joseph Knight succeeded John Abraham Heraud as dramatic critic of The Athenæum. Edmund Yates describes Heraud as "the long-haired epic poet," and as one of the theatrical critics he knew by sight, and says he "used to sit gaping at them with wonder and admiration." When Carlyle first came to London in 1834, Heraud lived in Ampton Street, close by Carlyle, who describes him as being exceedingly kedge about me, anxious beyond measure for golden opinions of his God-dedicated Epic of which I would not tell him any lie, greatly as he tempted me." Heraud was for a time assistant editor of Fraser; he also contributed to The Quarterly, and was dramatic critic of The Illustrated London News for thirty years. When he retired from The Athenæum the proprietors gave him a pension, and many a pleasant chat I have enjoyed with him when he came to receive it. He often spoke of the Carlyles and of his going with them over the house in Cheyne Row which they afterwards took, and where they lived for the remainder of their lives.

Heraud became a Charterhouse brother in 1873, and died there in 1887. He was eighty-eight years of age, and had survived all his friends. I was the only one from the outside world to follow his remains to the grave in St. Pancras Cemetery on a stormy afternoon in March. Of his daughter Edith he was very proud; her impersonations of Shakespearian characters are thought by many to have been extremely fine.

DRAMATIC CRITIC OF 'THE ATHENÆUM.'

Knight as dramatic critic.Knight's first contribution to The Athenæum was printed on the 25th of September, 1869. In those days the musical and dramatic gossip appeared together, so we have paragraphs from Chorley interspersed with those of Knight. Knight at once, with the greatest energy, supplied the paper with every detail of interest in his department, and we find in its pages a record of the drama of the day. During the last three months of 1869 it is mentioned that a new theatre is to be erected on the site of the Bentinck Club. 'The Octoroon' is being played at the Royal Alfred Theatre, and 'It is Never too Late to Mend' at the Grecian. 'Forbidden Fruit' at the Lyceum receives this censure: "M. Augier since his 'Mariage d'Olympe' has produced no work so unhealthy as this." Phelps is at Sadler's Wells. Mr. H. J. Byron makes his first appearance in London at the Globe on Saturday, October 23rd, in his own drama 'Not such a Fool as He Looks.' At the Surrey is a farce 'Who's Who?' a title now used for a very different subject; and at the same theatre is "a drama of the old-fashioned Surrey stamp, 'The Watch Dog of the Walsinghams,'" by Mr. Palgrave Simpson, in which "Madame Celeste appears in a variety of striking situations." Mr. J. R. Planché is superintending the stage arrangements at the St. James's, which is under the management of Mrs. John Wood.

Fechter as HamletIn December Fechter is giving twelve farewell performances at the Princess's previous to his departure for America. Of his impersonation of Hamlet it is stated that it "has not greatly altered during the years he has resided in England. It has all its old intelligence, beauty, and inadequacy. Many of the readings are good. The gestures and attitudes are almost without exception admirable; but the whole lacks inspiration. Instances of misconception of the meaning of Hamlet might easily be quoted. The words 'Into my grave' are given with a sadness out of keeping with the irony with which all Hamlet's speeches addressed to Polonius are coloured. It is clear from what Polonius afterwards says that Hamlet's words sounded like a query rather than a lament. In the First Folio, and in most editions, they are followed by a note of interrogation, which, however, in the edition of Messrs. Clark and Wright is omitted. When Hamlet, addressing Rosencrantz and Guildenstern, says, 'Is it not very strange? for mine uncle is King of Denmark, and those that would make mows at him while my father lived give twenty, forty, fifty, an hundred ducats apiece for his picture in little,' Mr. Fechter takes hold, with marks of contempt, of such a picture hanging from the neck of Guildenstern. This is a very pitiful piece of stage realism, and is as antagonistic to probability as to poetry. Mr. Fechter was supported by Miss Leclercq as Ophelia, Miss Elsworthy as the Queen, and Mr. H. Marston as the Ghost. On Wednesday Mr. Fechter appeared as Claude Melnotte, and on Friday as Ruy Bias."

Other events recorded are Mr. Burnand's new drama 'Mordern Grange,' to be produced at the Queen's; and Sothern's first novelty at the Haymarket, a two-act comedy by H. T. Craven. Charles Mathews is announced to leave for Australia on the 31st of January, 1870; and what seems now a regular old-world announcement is made, to the effect that "Mr. W. S. Woodin has returned to London, and is now giving at the Egyptian Hall his amusing entertainment 'My Carpet-Bag and Sketch-Book.'" Knight's presence at theatres was from the first hailed with pleasure by his comrades on the press, and so remained all through his life. A writer in Black and White on the 25th of November, 1899, well described him as "seeming to grow cheerier and jollier every day of his jolly life. Between the acts one hears his deep and hearty voice thundering out some almost Titanic laugh over amusing recollections of Phelps or Charles Mathews, Buckstone, Webster, Sothern, or any of the old gods who link us with Charles Kean or Macready."

'Theatrical Notes.'Knight has fortunately, in a volume with the modest title of 'Theatrical Notes,' given to the world in a concise form a selection from his articles on the drama which appeared in The Athenæum from November 7th, 1874, to December 27th, 1879. This was published by Lawrence & Bullen in 1893. The volume opens with Irving as Hamlet at the Lyceum. Fechter is referred to as "the most distinguished of his immediate predecessors in the role he now assumes. . . . Irving as Hamlet.Mr. Fechter rose slowly, through successive stages, looking carefully to his foothold. Mr. Irving has gone lightly and easily over the ground, and has reached the summit with but little exertion."

In the Introduction Knight states how he had watched for thirty years the average of a generation "the development of the stage in England. Thirty years constitute a long time as regards human observation and artistic progress. The first thirty years of the acted drama carry us from 'Ferrex and Porrex; or, Gammer Gurton's Needle,' to Marlowe's 'Edward II.'; another 'generation' gives us the First Folio Shakspeare. As civilization proceeds alteration is less evident. None the less the last thirty years of the English stage have witnessed more than one change, amounting practically to a revolution. Public interest in things theatrical, at the outset slumbering and apparently extinct, has flowered out afresh. The dramatist, once the most underpaid of literary craftsmen, has now the ball at his feet, and new theatres in the parts of London suited to their growth rise like exhalations."

Visit of the Comédie Française.But modest reference is made by Knight to the great services he rendered in bringing before the British public the high merits of the Comédie Française. Their first visit here was during the siege of Paris in 1870, when "a mere fraction of the public assembled to visit performances absolutely unequalled. It was not, indeed, until a movement for a complimentary banquet, the inception and execution of which belong to The Athenæum, had been set on foot that the playgoing world understood the opportunities of artistic enjoyment and education placed within its reach."

Knight states that materials are in hand for a second volume which will bring the matter up to date. Unfortunately, ill-health and over-pressure of work prevented this being accomplished.

Chairman of first Readers' Dinner.Knight had always highly appreciated, as all engaged in literature must, the services rendered by the proof-reader, and on the 11th of April, 1891, he took the chair at the dinner held to celebrate the foundation of the first Readers' Pension. Since then he had watched with great interest the work of the Readers' Pensions Committee, of which Lord Glenesk was President until his lamented death on November 24th, 1908. Four pensions have been founded, at a cost of just over two thousand pounds, and placed in the charge of the Printers' Pension Corporation. At the dinner in 1899, at which the Hon. W. F. Danvers Smith presided, it was resolved to establish, in addition, a pension specially for members of the Association of Correctors of the Press, and the third of these pensions has just been completed, the first recipient being Mr. Carbery, who was for more than forty years a reader on The Daily News.

THE FRENCH ACADEMY'S DICTIONARY.

To The Athenæum, in addition to criticisms of performances, Knight contributed reviews of books on the drama, and of others on subjects concerning which he had special knowledge. He occupied so prominent a position as a dramatic critic that his vast learning and his love for other studies are apt to be overlooked. I therefore make the following lengthy extract from a review which appeared on the 22nd of March, 1902, on a subject for which he had a great affection, that of philology. Knight in the French Academy's Dictionary.The occasion for it was the facsimile reprint of the famous 'Dictionnaire de l'Académie Françoise,' Paris, 1694:—

"No effort to supply the philological derivation of words was made in this first edition or in many after it, a subject for no special regret, considering that for much more than a century and a half after its appearance philological knowledge was in its infancy. No attempt at historical treatment is exhibited, and, a point more to be deplored, no illustrations of use are quoted, except from current speech. Those who hope from the first edition to reap such definitions, cynical, humorous, or prejudiced, as abound in the first edition of Johnson, and render its possession enviable when its authority has disappeared, will be disappointed. Everything is as decorous as it can be. Coarseness of speech is rarely to be found. There is no proof of the existence of that esprit gaulois which it was the joy of the nineteenth century to revive. All is in fact academic, respectable, and worthy of that roi soleil now old, persecuting, and sadly shorn of his beams to whom, in language of supreme adulation, the book is dedicated. . . .

"With all its faults and shortcomings on its head, the 'Dictionnaire de l'Academie Françoise' is what Prof. Dupont, of the University of Lille, to whom the reproduction is due, calls it, 'un monument tres venerable et un document tres precieux.' For reasons already in part exposed, it is all but useless to those who seek a dictionary for general purposes: to the student of what has been called the Augustan period of French literature it is invaluable. The language with which it deals is that of the acknowledged masters of French style, and the prophecy of Fénelon, in his 'Lettre à l'Académie,' is to a great extent fulfilled:—

"'Quand notre langue sera changée, il servira à faire entendre les livres dignes de la postérité qui sont écrits en notre temps. . . .Un jour on sentira la commodité d'avoir un Dictionnaire qui serve de clef à tant de bons livres. Le prix de cet ouvrage ne peut manquer de croitre à mesure qu'il vieillira.'

"In this respect even it is far from complete. Purely academic in origin, it has the fault of much academic work of omitting those current locutions which are most apt to change in form, the preservation of which is most to be desired. One has only to compare with the dictionary the special lexicons of authors who have come to be regarded as classic which are numerous in France. That or rather those to Molière are scarcely in point. Molière's writings were of course accessible, and he himself had been a score years dead at the time when his language was noted. A lexicon composed by the early Academicians was, however, little likely to pay attention to the utterances of an actor and a playwright. One has only to look at the list of Academicians prefixed to the work to see what ecclesiastical influence was arrayed against the actor to whom the rites of Christian burial were denied. True, the list includes Jean de la Fontaine, Nicolas Boyleau Despreaux, Thomas Corneille, Bernard de Fontenelle, François de la Mothe Fenelon, and others of equal eminence in literature. Ecclesiastical and aristocratic influences were, however, sure to prevail. Few words employed by Molière, and to be found in the 'Lexique' of M. Livet or that of MM. Despois and Mesnard, are missing, though among those which do not appear is 'canons,' so frequent during the seventeenth century in a particular sense: 'Sont-ce ses grands canons qui vous le font aimer?' ('Le Misanthrope,' II. i.) Loret, 'La Muze Historique,' under the date 1656, speaks of a man

par extravagance

Portant des canons d'importance,

Chacun plus grand qu'un parasol.

The word 'canons' was applied to several different portions of dress appertaining to the leg. About 1668 this sense of it fell, according to Richelet, into disuse, and at the time when the dictionary first saw the light was supposedly obsolete. It should, of course, have been retained, as is attested by its appearance in later editions. From modern dictionaries of to-day it has almost disappeared. . . .

"A dictionary of a given date is in the full sense a contribution to the history of language, a fact the full significance of which philologists have now realized. The idea of tracing that history by means of quotations successive in date belongs wholly to to-day. In few things is the dictionary before us more instructive than with regard to the growth of accents. The very first word in the preface, itself unaccented, is aprés, with the accent acute. Among the words unaccented on the first page are rhetorique, premiere, celebres, siecles, &c. In poëtique and similar words diæresis takes the place of other accent. A study of the first and following editions might help to settle the time when the acute accent or the circumflex took the place of the elided s in words such as estourdi, ctourdi; arrest, arrêt.

"The charge that the dictionary makers had too far expurgated the language by omitting expressive words employed by early writers was often advanced, La Bruyere and Fenelon being among those by whom it was brought. La Fontaine, a constant attendant at the meetings of the Academic, could not obtain admission for words from Marot and Rabelais. Froissart was too early, the dictionary beginning practically with Montaigne. Among the words that appear is effervescence, under 'ferveur.' It should be remembered, however, that Madame de Sevigne, on hearing it employed by her daughter, said, 'Comment dites-vous cela, ma fille? Voila un mot dont je n'avais jamais oui parler.' Savoir-faire, according to Le Père Bouhours, is a new term, which will not last is perhaps already out of date."

The review closes with warm words of commendation of Prof. Paul Dupont, who owns his indebtedness to M. Leon Moy, who died doyen of the Faculty of Letters of the University of Lille.

'HYPNEROTOMACHIA POLIPHILI.'

'Hypnerotomachia Poliphili'Knight was a thorough bibliophile, and this side of his character is exhibited by a review which appeared on the 31st of December, 1904, of a book which he characterized as "an unprecedented boon to the scholar and the artist. No lover of fine works will be content to be without it." This was the famous 'Hypnerotomachia Poliphili; or, Strife of Love as seen in a Dream by Polifilo,' issued for the first time in facsimile by Messrs. Methuen:—

"Over a book of the kind the scholar will rejoice and the artist jubilate. The work, though virtually unread, is known to be in many respects unique. It is a notable product of the Aldine press, and the masterpiece of Venetian book-illustration. Everything about it is mystery and problem; its authorship, long obscure, was only ascertained when a close student discovered that the first letters of the thirty-eight chapters into which the book is divided gave the following device: 'Poliam frater Franciscvs Colvmna peramavit.'

"A Dominican of the name of Francisco Colonna died in Venice in July, 1525, at the age of over eighty years. Little or nothing definite is known about him, though Renaissance Italian literature abounds in conjecture concerning him, much of it demonstrably inaccurate, and almost all of it void of authority. Rabelais mentions the author under the name Polyphile in the ninth chapter of the first book of 'Gargantua,' misnaming his book, which he calls songe d'amours, and coupling him with Orus Apollon [Horapollo], a Greek grammarian of the fourth century, the author of 'Hieroglyphica,' a work printed by Aldus in 1505 with the 'Vitæ et Fabellæ Æsopi.' Temanza, the biographer of Venetian architects, who flourished in the eighteenth century, devotes to him some space, and assigns him to the illustrious family of the Colonna. Crediting Columna, or Colonna, himself with the adventures of Poliphilus, he builds up a love romance and makes Polia a contraction of the name of Ippolita, niece of Teodoro Lelio, a bishop of Feltre. Against this supposition, founded upon a MS. note now no longer traceable in a copy of the work formerly existing in the library of the Dominican fathers delle Zatere, it may be urged that Polia herself declares her baptismal name to have been Lucretia: 'Et postomi il præstante nome della casta Romana che per il filio del superbo Tarquino se occise.' By the same ingenious fiction Polia is said to have been attacked by the plague which ravaged Treviso, to have vowed to take the veil in case she recovered, and, keeping her oath, to have driven her lover into the cloister. This ingenious and indefensible theory inspired Charles Nodier, who founded on it in the Bulletin des Amis des Arts his last nouvelle. A much more plausible interpretation is that favoured by M. Claudius Popelin, the latest and best translator of the work, that Polia is the name of an imaginary mistress, such as the great Italian poets, and, after them, the writers constituting the Pléiade, devised, transmitting the fashion to English successors of Tudor and Stuart times. Now the name Polia, which the author expressly assigns his mistress, is the Greek adjective πολία, indicating grey hair, and used to express antiquity. A lover of Polia is, then, a lover of antiquity. This view is not only ingenious, but also defensible. It is borne out by the whole tenor of the work, which has been supposed to be, among other things, a protest in favour of classical architecture against the aggression of Gothic, at that time overwhelmingly manifest. . . .

"Perfect copies, especially in Grolier bindings—Grolier appears to have greatly admired the work—are of high value. The finest existing copy must be that on vellum, and in a Grolier binding, belonging to the Duke of Devonshire. Other Grolier copies are, or were, in the possession of Lord Spencer, in a French collection, and elsewhere. In the British Museum, which has no Grolier copy, is one which belonged to Grolier's great rival, Tommaso Maioli. The work, which originally appeared in a superb folio, a shape it now resumes, has been frequently reprinted, and in a sense translated."

The copy of the original edition of the 'Hypnerotomachia Poliphili' referred to, Mr. Guppy informs me, is now in the possession of the John Rylands Library. Mr. Guppy says: "It is a very fine copy of the original edition of 1499, which was formerly in the library of the famous patron of literature and learning Grolier, and is clothed in one of his sumptuous bindings. That in the Duke of Devonshire's library at Chatsworth is the only perfect copy of the work printed on vellum. Apparently three copies were printed on vellum, but the other two are imperfect. Our copy, I need scarcely add, is on paper."

'FESTUS.'

'Festus.'Knight was a great lover of poetry, and from his schooldays knew, as we have seen, much of Milton by heart. He was also a warm admirer of 'Festus,' every line of which was familiar to him. The obituary notice of Philip James Bailey which appeared in The Athenæum on the 13th of September, 1902, was from his pen. Knight describes Bailey as "sweet, gentle, and rather timid in nature—qualities he seems to have inherited from his father. Though not wanting in resolution, Bailey was a little alarmed at the pother his book had caused and at the further innovations to which it gave rise. While philosophical in basis, it has a strongly sensuous turn which in the later editions becomes less evident. A work of youth, it is infused throughout with imagination and passion.

"In the dedication to his father, preserved in the various English editions, he says:—

Life is at blood-heat every page doth prove.

So much babbling of lovers is there that Lucifer feels bound to protest and declare:—

And we might trust these youths and maidens fair,

The world was made for nothing but love—love.

Now I think it was made but to be burned.

"According to his teaching, which is, of course, in no respect individual, youth is the period for love, and Festus asks in an inspired rhapsody:—

And if I love not now, while woman is

All bosom to the young, when shall I love?

Who ever paused on passion's fiery wheel?

Or, trembling by the side of her he loved,

Whose lightest touch brought all but madness, ever

coldly short to reckon up his pulse?

The car comes and we lie and let it come:

It crushes kills what then ? It is joy to die.

These ecstasies and others even more pronounced did not prevent Bailey from regarding with something like dismay the subtler and even more fervent utterances of Mr. Swinburne, Rossetti, and younger poets of their schools. The reputation he had won as an amourist faded in later days, and it is as a didactic poet that he has of late been most worshipped. In his gnomical utterances he has much in common with Walter Savage Landor, whom in single line and distich he occasionally recalls. There is little conscious imitation, the only poet whose method he directly follows being Milton. Where he talks of men

Huger than those our childhood's chap-books brand;

Or all whose deeds till now defile romance;

Albadan and those monstrous, sire and son,

Whom Amadis, the flower of knights, o'erthrew,

.......so to win

His Oriana bright as Miréfleur,

it is impossible not to recall the lines in 'Paradise Lost' concerning

. .all who since, baptized or infidel,

Jousted in Aspramont or Montalban,

Damasco or Marocco or Trebisond;

and 'Paradise Regained,' when Agrican besieged Albracca,

thence to win

The fairest of her sex, Angelica.

Short passages of signal beauty and Landor-like grace of utterance are numerous. A few must suffice:—

Just when the stars falter forth, one by one,

Like the first words of love from a maiden's lips.

There was no discord—it was music ceased.

Locks which have

The golden embrownment of a lion's eye,

a simile alike bold and happy.

Mountain-tops, where only snow

Dwells and the sunshine hurries coldly by.

The grand old legend of humanity.

"We are not now dwelling on the claims of 'Festus,' tempting as is the task in the case of a work which is slipping from the ken of modern readers, and for which is reserved a glorious revival. Were it otherwise we could fill pages. We find in our favourite edition of 'Festus' more passages marked for approval or quotation than in any work of its class. The modern reader forgets, or has never heard, that on its first appearance Tennyson said he could scarcely trust himself to say how much he admired it for fear of falling into extravagance, that Thackeray, then a power in the land, said it had poetry enough to set up fifty poets; that, in fact, all the recognized critics whose opinions survive bore testimony to its supreme gifts. When one takes into account that it was written between twenty and twenty-three it may count as in its way unique. Unfortunately, it was at once blossom and fruit, and what its author subsequently accomplished is far from being of equal interest or value. . . .

"Many of the lyrics in 'Festus' are noteworthy, and one or two of them are inspired. Though a desirable possession, the first edition is not always the best form in which to read it. In later editions some crudities are rectified, and some metrical advance is recognizable."

Knight wrote an occasional poem himself, and his sonnet 'Love's Martyrdom' is No. CXIX. in William Sharp's 'Sonnets of the Century.' By the kind permission of the Walter Scott Publishing Company, I am able to reproduce it here:—

LOVE'S MARTYRDOM.

Sweet we will hold to Love for Love's sweet sake,

Seeing Love to us must be his own reward:

Haply we shall not find our task too hard,

Nor suffer from intolerable ache.

Yea, though henceforth our lives asunder break,

From every comfort-giving hope debarr'd,

Love may support his martyrs, and the scarr'd

And wounded heart may triumph at the stake.

Sweet not for us Love's guerdons : not for us

The boons which wont Love's constancy requite;

No whisper of low voices tremulous,

Kiss, or caress,; no breath of Love's delight:

Yet will we hold our joyless troth, and thus

Achieve Love's victory in Fate's despite.

Another instance of Knight's love of the sonnet is given in The Athenæum for the 13th of January, 1906, where he quotes the following sonnet of Félix Arvers, and afterwards "ventures on a free and inadequate" rendering of it:—

SONNET D'ARVERS,

'Sonnet d'Arvers.'

Mon âme a son secret; ma vie a son mystère,

Un amour éternel en un moment conçu:

Le mal est sans espoir aussi j'ai du le taire,

Et celle qui l'a fait; n'a jamais rien su.

Hélas! j'aurai passé pres d'elle inapercu,

Toujours à ses côtés et pourtant solitaire;

Et j'aurai jusqu'au bout fait mon temps sur la terre,

N'osant rien demandé et n'ayant rien reçu.

Pour elle, quoique Dieu l'ait fait douce et tendre,

Elle suit son chemin, distraite et sans entendre

Ce murmure d' amour soulevé [élevé?] sur ses pas.

A l'austère devoir pieusement fidele,

Elle dira, lisant ses vers tout remplis d'elle,

"Quelle est donc cette femme?" et ne comprendra pas.

Translation by Joseph Knight

One sweet, sad secret holds my heart in thrall;

A mighty love within my breast has grown,

Unseen, unspoken, and of no one known;

And of my sweet, who gave it, least of all.

Close as the shadow that doth by her fall

I walk beside her evermore alone,

Till to the end my weary days have flown,

With naught to hope, to wait for, to recall.

For her, though God hath made her kind as sweet,

Serene she moves, nor hears about her feet

These waves of love which break and overflow,

Yea! she will read these lines, where men may see

A whole life's longings, marvelling, "Who is she

That thus can "move him?" and will never know.

EDITOR OF 'NOTES AND QUERIES.'

Editor of 'N. & Q.'It was in July, 1883, on the death of Turle, that Knight became Editor of Notes and Queries, and from that date until the time of his death our friendship and affection yearly increased. At first the enormous amount of correspondence Knight had to wade through as editor proved very irksome to one who was used to so much activity; but as he began to know those with whom he corresponded, many became his friends. His vast learning they held in respect, while his lovable nature and courteous manners endeared him to all, and rendered him peculiarly fitted for the Editorship of a paper with such special characteristics as 'N. & Q.,' of which the Jubilee was celebrated in the number for the 4th of November, 1899, Mr. Knight contributing the following introductory article:—

Jubilee of 'N. & Q.'"It has fallen to my lot to superintend the production of the one hundredth volume of Notes and Queries, and thus in a sense to preside over its jubilee. Fifty years constitute a considerable period in the life of any man, and it is scarcely to be expected that the originator of a periodical will take any personal share in the proceedings at its fiftieth birthday. In the case of a work such as Notes and Queries the probabilities of any such active participation are reduced to a minimum. Not at all the sort of idea to germinate in the mind of active strenuous youth is that of a work of this class. It is necessarily the conception of the ripe scholar seeking further to gratify that thirst for knowledge which is the strength or the 'infirmity of noble minds.' How much effort of how many men has been necessary in order to bring Notes and Queries to its present standpoint of efficiency and to its position as the indispensable companion of every earnest literary writer Mr. Francis, in his admirably zealous and competent record of its past history a work which he alone could have accomplished—now tells us, supplying a bright and conscientious record of things beyond editorial ken, and taking on himself a burden of which the editor was incapable. To that labour of love, as he rightly styles it, and to the assistance rendered him by other attached friends such as Notes and Queries has happily been ever able to boast, I draw the reader's attention. Of my own connexion with Notes and Queries it behoves me, even when bidden to speak, to say little. My easy and agreeable duty has been to maintain, so far as I was able, the traditions of my predecessors. If the task has been satisfactorily accomplished, and if Notes and Queries, as I venture to think, stands now as proudly eminent as it has ever stood, the merit is not in any sense mine. A staff of brilliant contributors keeps a constant and sometimes overflowing and unmanageable supply of matter, with which I have only so far to deal as to prevent frequent and needless repetition. These contributors consist of erudite and, in a sense, leisured scholars such as were, to mention two only who have passed away during my tenure of office, the Rev. W. E. Buckley and the Rev. E. Marshall, with others still happily living. Beside these come the ripest scientists, antiquaries, philologists, and folk-lorists. I do not hold an occasion such even as the present to justify any revelations of the identity hidden behind familiar pseudonyms or initials. I may say, however, that this cloak of anonymity has again and again shrouded the most illustrious individualities the principal statesmen, senators, warriors, ecclesiastics, and thinkers of the day, Prime Ministers, Commanders-in-Chief, and sommités of every description. If I might be allowed, indeed, to renew a request which, as Mr. Francis shows, has previously been made, it would be that some of those who obscure themselves behind a single letter would, to paraphrase Waller, 'come forth' and suffer themselves 'to be admired' and helped. The search after knowledge is as honourable as it is fascinating, and the most eminent in the land need not blush to appeal to the all-embracing wisdom or information possessed by the aggregated contributors to Notes and Queries.

"Nothing could be more grateful to me than to thank those who during my tenure of office have kept Notes and Queries at its present splendid height, and won for its editor in some outside circles a credit for erudition he is as far from claiming as from meriting—since, indeed, those are not wanting who hold that the editor is bound to possess the omniscience which his contributors supply. 'You the editor of Notes and Queries! ' spoken with flattering wonder, say those who marvel 'how one small brain could carry all he' was supposed to know. I have, however, as I have previously said, no more right to express my gratitude than any other who benefits. Name and work speak aloud for themselves, and my only responsibility is that of the peacemaker who tries to prevent discussion passing the bounds of courtesy and employing terms that may rankle, or words that may gall a task, on the whole, lighter than might be imagined.

"It seems but yesterday that I stepped into the shoes of my amiable and accomplished friend and predecessor Turle, yet I now see that no long time needs elapse before I might be in the position of seeing myself the longest occupant of the editorial chair. During the years in which I have sat in this seat of honour, the two great national undertakings of the 'New English Dictionary' and the 'Dictionary of National Biography,' now rapidly approaching completion, have made their public appearance, together with that other and hardly less important work 'The Dialect Dictionary.' With these I am proud to find Notes and Queries closely connected. Association with them has added greatly to its claims to recognition. Under the influence of the studies thus prosecuted, knowledge of our illustrious dead is widely disseminated, and sound views on philology are beginning to spread beyond the narrow limits of professors and class-men. There still are philological free-lances who, refusing to join any regularly constituted force, fight for their own hand; but their cause is hopeless and their protests are vain. In the growth, expansion, and progress of these works what is of most interest and importance in Notes and Queries is found. The rest, so far as I am concerned, consists of records of pleasant and honouring intimacies formed and of others broken by the great and inevitable disrupter of all things.

"One more change, however, with which I have been associated is the third migration of Notes and Queries, in common with the Athenæum, in March, 1892, from its old premises in Took's Court, now occupied by Government offices, to its present quarters, and the appearance of a series of views illustrating the old offices and other spots of antiquarian interest in the neighbourhood. See 8 S. i. 261 et seq. "Contributors to the First Series are still in our midst. They may be more even than we are aware for who shall say under what disguises some who now sign their names at first concealed themselves? Such must, however, be comparatively few. Those who remain and those who are coming on are animated by the same spirit, preserve the same traditions, and hold aloft the same banner. Thoughts of battle are at present in men's minds, and the fact may justify an illustration not likely otherwise to be employed. The ranks of a corps are depleted and are filled again, yet the regiment is the same. Its men are still preux, its colours are unchanged, or when torn to shreds are renewed, the esprit de corps endures, and the very nicknames—heroic, comic, or affectionate—are preserved. Through the changes Mr. Francis so graphically depicts, Notes and Queries remains Notes and Queries, renders the same service, inspires the same devotion. I might almost address my associates and supporters as Henry V. addressed his scanty force at Agincourt :

- We few, we happy few, we band of brothers.

A band of brothers the writers in Notes and Queries have always constituted, and there is, I venture to think, no other periodical in the world in which exist such bonds of sympathy among its contributors and such cordial support of those in a position of 'brief authority.'"

The affection with which he was regarded by its contributors was worldwide, and friends across the seas wrote to me not long before his death, wishing him to be invited to a banquet in 1909 to celebrate the Golden Jubilee of Notes and Queries. His own contributions to the paper were so modestly put that they are difficult to trace, but notable among these was his tribute to our late beloved Queen Victoria, which appeared in 'N. & Q.' on Saturday, the 26th of January, 1901. Knight was desirous that fitting tribute should be rendered, but was nervous about writing one to appear the same week, the time being so short. I telegraphed to him how anxious I was that it should appear, and in a couple of hours he brought me the following, which was printed on the first page of the number. I mention these details to show how truly Knight had the pen of a ready writer:

VICTORIA REGINA ET IMPERATRIX.

Death of

Queen

Victoria."The saddest task that has yet fallen to Notes and Queries is the record of the national loss.

"Born 24 May, 1819 ; died 22 January, 1901. These are the simple outlines of fact which an empire's love and an unparalleled historic record have filled in until a picture is constituted the noblest, the grandest, the most splendid upon which the world has gazed. The reign has been longer as it has been more brilliant than that of any previous sovereign. At present Britain may say with Queen Constance.

- To me and to the state of my great grief

- Let kings assemble.

All rivalries and jealousies are forgotten, the rulers of the whole world of civilization bring homage and tribute. No chronicle attests a state of affairs so solemn, so sorrowful. Our thoughts are wholly occupied with the illustrious dead. Yet even when so absorbed what temptation to swelling pride presents itself! What, beside Victoria, are Semiramis and Cleopatra? What even is our own Elizabeth, who presided over the birth of empire, compared with the Queen who has borne its full state and burden?

"That the tragedy of recent days has shortened and clouded her life there is cause to fear. Her personal empire has, however, been that of peace. Conspicuous and exceptional as in all respects has been her career, its chief glory is that it has maintained, in a time when licence prevails, the purity of womanhood, the sanctity of the family. On the wisdom of Victoria, her recognition of the principles of constitutional rule, the gain to her councils of her personal sway, history will speak. The meanest of her subjects know, however, how her personal life has been worthy and pure, how it has been founded on morality and established in righteousness, an example of the principles on which national greatness is founded and safe-guarded. As queen, as wife, as mother, in all that is typical of England at its best, she claims and receives our homage, our admiration, our tears."

'THE DAILY GRAPHIC.'

The Daily

GraphicFor twelve years (1894 to 1906) Knight was the dramatic of The Daily Graphic, and I am indebted to Mr. Hammond Hall, who was editor during the whole of that period, and to Mr. Lionel F. Gowing, the present editor, for the following reminiscences.

Mr. Hammond Hall speaks of Knight's extreme conscientiousness in his work, and the affection which he inspired in everybody with whom he came in contact:

"His duties on The Daily Graphic were very trying because, owing to the exigencies of morning newspaper production, it was necessary that his copy should be in the hands of the printers at an hour little later than that of the fall of the curtain; but his criticism was never scamped; it was always scholarly and thoughtful. Whenever it was possible to do so, he would attend the dress rehearsal of a new play. Then he would be present at the public representation until the time for him to make his way to The Daily Graphic. His daughter, or some other deputy upon whose judgment he could rely, waited in the theatre until the curtain fell, and brought on to him impressions of the closing scenes and of the demeanour of the audience which sometimes, but not often, induced him to make alterations in, or additions to, his proof.

"The critical value of his written notices was diminished somewhat by his exceeding good nature. He could not forget that the failure of a play, while a matter of merely passing interest to the public for whom he wrote, might entail serious loss and suffering to the producer and the players. I have known him to come into the office bubbling over with indignation. 'This is absolutely the worst play I have ever seen. It is an insult to offer it to the public, and I hope you will let me say so in The Daily Graphic' 'Certainly,' I would reply; 'I rely entirely upon your judgment. If the play is a bad one, say so as emphatically as you like.' I knew well that the unkindest word Joe Knight would deliberately write about the honest work, however imperfect, of any human creature would give him more pain than it would give its object. His judgment, however, was always sound. He knew not only whether a play was good or bad from the point of view of dramatic art, but whether it would satisfy the public. He would have made the fortune of any theatrical manager who could have retained him as adviser, and acted upon his advice.

"How beloved he was! One might have supposed that the younger members of the editorial staff had nothing else to do, so ready were they to wait upon him on his arrival from the theatre. They had their reward when his writing was finished and he would regale them from his store of anecdote and reminiscence.

Death of

William

Terriss."At one of the excellent dinners he sometimes gave at the Garrick Club, a message was brought to one of the guests I think it was Mr. Pinero who announced that Terriss the actor had just

been assassinated at the entrance to his theatre. Knight was silent for many minutes, took no notice of remarks addressed to him, and seemed to be oblivious of his duties as host. Then he began in a low voice to talk his thoughts, full of appreciation of the dead man, and of sympathy for those who would suffer most severely by his loss.

Mafeking

night."No one who was in London on the night on which the news arrived that Mafeking had been relieved can forget the astonishing

swiftness with which the news spread, and how streets which a minute before had been half-empty, seemed to be instantly filled

with a wildly exultant crowd. Knight was at a theatre where the news was proclaimed from the stage. There was a scene of great

enthusiasm, the audience standing up, waving their handkerchiefs, and singing the National Anthem. Knight was as much pleased as anybody, but not unduly excited, and settled himself down with his customary calm to criticize the remainder of the play. On his coming out of the theatre, however, the shouting mass of humanity in the street brought home to him the full significance of the news of the night. The contagion of collective emotion overpowered him. 'My eyes were streaming with tears,' he told me, 'and I was in danger of being mobbed for a pro-Boer before I could get into a cab.'

"What a memory the man had! I never knew him to consult a work of reference or make a misquotation. He seemed to have all the classics by heart, and his recollections of the interesting people he had known, and the interesting things they had said and done, appeared to be inexhaustible.

Dinner at the

Savoy."I had the privilege of taking the chair at the dinner which his colleagues gave him at the Savoy on the occasion of his retirement from The Daily Graphic. He made a speech full of personal anecdote of a deeply interesting character, and after dinner the most of us gathered round to listen to an exchange of reminiscences between him and his old friend Ashby-Sterry."

Mr. Gowing tells me that "Knight always remained to correct his proof—a necessary precaution, as his handwriting was not of the most legible—and frequently he would then go to the Garrick and write a notice of the play for the next day's Globe, before going home to bed," so that it should appear the same afternoon. He never wrote a line in the theatre.

The Radical defeat in 1895 tempted him to the following jeu d'esprit, which appeared in The St. James's Gazette on July 23rd, 1895, and which I give with the cordial permission of Mr. C. Arthur Pearson. The same day Knight brought the paper and read the lines to me, laughing so heartily that he could hardly get through them:

THE BANNERMAN'S LAMENT.

'The

Bannerman's

Lament.'

Wherefor, wherefor do ye greet,

Tammy Ellis, Tammy Ellis?

At the Radical defeat?

Tammy Ellis mine.

Weel we ken ye were at faut,

Tammy Ellis, Tammy Ellis;

Nappin' this time ye've been caught,

Tammy Ellis mine.

'Tisna for the siller lost,

Tammy Ellis, Tammy Ellis,

I maun wail and count the cost.

Tammy Ellis mine.

But my merry men so true,

Tammy Ellis, Tammy Ellis,

Ruined, vanquished, all through you,

Tammy Ellis mine.

Ken ye weel, ye feckless loon,

Tammy Ellis, Tammy Ellis,

What men of micht ye've overthrown!

Tammy Ellis mine.

Within Dalmeny's gilded bowers,

Tammy Ellis, Tammy Ellis,

What vanquished victor groans and glowers?

Tammy Ellis mine.

In Hawarden how the grand old chief,

Tammy Ellis, Tammy Ellis,

Not e'en in post-cards finds relief?

Tammy Ellis mine.

And there are woes more sacred yet,

Tammy Ellis, Tammy Ellis,

Thine offspring of Plantagenet,

Tammy Ellis mine.

Thine too Newcastle's doughty Knight,

Tammy Ellis, Tammy Ellis.

Dour in council, fierce in fight,

Tammy Ellis mine.

Irish boroughs bought and sold,

Tammy Ellis, Tammy Ellis

Celtic seats wi' Saxon gold,

Tammy Ellis mine

Canna make amends, I wot,

Tammy Ellis, Tammy Ellis,

For evil sic as ye hae wrought,

Tammy Ellis mine.

Hide, mon, yere dishonoured pow,

Tammy Ellis, Tammy Ellis,

Where nae man may see and know,

Tammy Ellis mine.

Where nae mortal sees or hears,

Tammy Ellis, Tammy Ellis,

And leave me, leave me to my tears,

Tammy Ellis mine.

'DICTIONARY OF NATIONAL BIOGRAPHY.'

'D.N.B.'Of Knight's writings apart from the daily and weekly press, his contributions to the 'Dictionary of National Biography' stand pre-eminent. In this monumental work, which we owe to the patriotism of George Smith, there are no fewer than five hundred biographies of actors and actresses by him, his name appearing in the list of contributors in all but four of the sixty-six volumes. Thanks to the courtesy of my friends Messrs. Smith, Elder & Co., I am able to give a complete list of these, and I have placed it at the end of this memoir.

LIFE OF D. G. ROSSETTI.

D.G. Rossetti.Another work of Knight's, the life of Dante Gabriel Rossetti, published by Walter Scott in 1887, has been pronounced by many the best life of Rossetti that has yet been written; and Mr. William Michael Rossetti in his 'Reminiscences' (published by Messrs. Brown, Langham & Co. in 1906), in mentioning how his "brother valued his [Knight's] discernment in poetical and other matters, and liked his manly geniality, harmonizing with a very handsome exterior," states regarding this life that "among all the records of him [his brother] which have appeared, none is written in a kindlier or fairer spirit than that of Mr. Knight—who can understand a man of genius, prize his fine personal and intellectual qualities, and make reasonable allowance for his peculiarities and defects" (vol. ii. pp. 331–2).

The following letter from Dante Rossetti to Knight appears in Knight's life of Rossetti, and is inserted by permission of the Walter Scott Publishing Company: it is in reference to an article written by Knight which appeared in Le Livre:—

- Westcliff Bungalow, Birchington-on-Sea, Kent

- 5 March, /82.

- Westcliff Bungalow, Birchington-on-Sea, Kent

MY DEAR KNIGHT, Curiously enough, I had not till to-day seen Le Livre for December and read (though I had heard of it from Watts) your generous and unforgetful praise of one, whom you could not speak of more warmly if we met as often as I could wish. Of the article's purport I hardly have a right to speak further, but can more pardonably dwell on its true literary quality. I do not gather, of course, whether the French is your own or rendered by another. In either case the tone could not be more akin to the language. I have come here for a short time, being much out of health. Watts is with me to-day, and sends his truest remembrances from the sofa where he is reading your article. I have not seen the Marstons for some time, but must try to do so on my return to London, and I do hope you and I may yet again foregather. I have been penning a few verses to-day in lack of other occupation. I write with this to Ellis & White to send you a copy of the new edition of my old Poems. In 'Sister Helen' (which I remember you always liked) there is an addition which (though it sounds alarming at first) has quite secured Watts' suffrage.

- With love from what is left of me,

- Yours affectionately,

- D. G. Rossetti.

- Yours affectionately,

This was probably the last letter Dante Rossetti ever wrote. He died on Easter Sunday, the 9th of April, 1882. Mr. Theodore Watts-Dunton, in an affectionate appreciation which appeared in The Athenæum of the following Saturday, describes him as "one of the most rarely gifted men of our time," and says that "a life more devoted to literature and art than his it is impossible to imagine."

Mr. William Rossetti says that when Knight was preparing the life of his brother he "undertook to show him any letters in my possession. My wife got some together, which I read not at all, or only very cursorily. She handed the bundle over to Knight, including a letter by Gabriel to [Christian name ?] Brown. In this Gabriel cautioned Brown not to mention some particular detail to Knight, he being (the phrase was this, or something like it) 'an awful old gossip.' Knight read the letter in my wife's presence, and my wife then returned it to me, both laughing and confused, and told me of the small pitfall into which she had dropped."

Mr. Rossetti informs me that the time he saw Knight oftenest was at his brother's house from 1864 to 1868, and "he was then a remarkably handsome, prepossessing-looking man, free from any sort of affectation, open and amusing in talk, without being bitter or unkind. Occasionally he read to Gabriel and me some verses of his composition, and we both thought them, and I think Swinburne did too, of a degree of merit much surpassing the average."

CYRANO DE BERGERAC.

Cyrano de

Bergerac.In August, 1898, Knight gave me a copy of The Fortnightly Review for that month containing an article of his on 'The Real Cyrano de Bergerac.'[1] In it he states:—"That next to nothing

concerning the real Cyrano is known, not only to Englishmen who have written concerning M. Rostand's play, but to the vast majority of Frenchmen, is but too evident. Numerous as are the editions of his works which were published shortly after his death, they are now, for the most part, unknown or inaccessible, and the modern editions by which they have been replaced are untrustworthy, emasculated, unedited, and abridged. . . . Whatever may have been the extravagances, the mannerisms, and the faults of Cyrano, he was a man of high intellect, and not a buffoon: he was in scientific knowledge far in advance of his time, and he is to be remembered among the most fearless advocates of freedom of thought. His friends were men of capacity and eminence, and if some of his

boldest utterances were, on account of licence or even obscenity, so emasculated that the world even now is not in possession of his geniune works, it is because, though Cyrano, like Rabelais, was

prepared to speak the truth and the whole truth, jusqu'au feu exclusivement, his friends, to whom the care of his reputation was left, and especially his clerical editor, were neither so bold nor so enlightened."

In the notice of the play as performed at the Lyceum, which appeared in The Athenæum on the 9th of July, 1898, Knight accords to M. Rostand full praise for the high quality and conspicuous merit of the play, although its merits are not wholly or principally dramatic:—

"As literature its position is unassailable, and the beauty and flexibility of its versification are held to promise a new lease of life to a form of composition that is necessarily conventional, and in this country has been regarded as artificial. . . .

"The deeds of Cyrano as preserved in history constitute the greater portion of the play; his imaginary adventures in the sun and the moon are introduced into the action; and the style, 'pointu et précieux à sa plus haute expression,' as Gautier says, is admirably caught. In showing Cyrano in love with a précieuse and animated by a spirit of self-denial the most exemplary, not to say inconceivable, in literature, M. Rostand is, of course, justified. Cyrano was in fact a libertine as well as a swashbuckler and a ruffler. He was also, as his portraits attest, a handsome man of a Southern type, with a nose large, no doubt, but in nowise preposterous not larger, for instance, than that of M. Hyacinthe, over which Parisian wits made merry a generation ago. Jesting on the nose of Cyrano was the readiest way to obtain four inches of steel in the ribs, and was accordingly seldom practised. . . .

Coquelin."As a whole, however, 'Cyrano de Bergerac' is picturesque and spectacular rather than dramatic. It has scenes that are dramatic, and others that are tender. It must be remembered, moreover, that the work was written for the Porte Saint-Martin, and not for the Comedie Francaise. It supplies M. Coquelin with a part into which, as M. Rostand tells us, the soul of Cyrano has passed. Without opposing a statement the full significance of which we scarcely comprehend, we concede that M. Coquelin's

performance is remarkable in picturesqueness, and marvellous as a revelation of method. Happier in portraying the comic aspects than the romantic, he fails to assign the part the distinction which is, at least, among its potentialities. He reminds us of Don Annibal or of Antient Pistol rather than of Don Quixote or D'Artagnan." SHERIDAN.

Garrick and

Sheridan.Knight also wrote a life of Garrick, published by Kegan Paul in 1894, and edited 'The Dramatic Works of Sheridan,' issued by Henry Frowde in 1906. On the last day of the latter year he

wrote to me in reference to it:—

"To-day I left with Mr. Randall for you a copy of the Sheridan, which, though of little worth, you will prize as in fact mine. To-morrow will begin 1907, which I trust will be a happy and prosperous year for yourself and all who belong to you. I left for your perusal a very kind and effusive letter of our good friend Ebsworth. Your nephew will tell you my views on that. I am very proud of his good opinion, which is indeed a much coveted and very honouring tribute. I don't want, however, to push myself or blow my own trumpet in 'N. & Q.' Do with the matter, however, as you wish. God bless you at this and every other time."

First

Circulating

Library.Although his contribution to the Sheridan volume is limited to 32 pages, he brings much of his own special knowledge and research

to the brief and succinct notes. For instance, in reference to the formation of a Public Circulating Library in London he quotes the first entry relating to circulating libraries in the 'New English Dictionary,' being an advertisement dated June 12th, 1742, Librarian Samuel Fancourt; and in 1783 The Gentleman's Magazine, p. 941, mentions a statement that "the first circulating library was opened by the Rev. Mr. Fancourt. . . . fifty or sixty years ago. It was afterwards removed to Crane Court, Fleet Street " ('N.E.D.,' ii. p. 427). Mr. Fancourt died in poverty in London at the age of

ninety in 1768. There is a full and interesting account of him and his projects in the 'Dictionary of National Biography.'

Ebsworth's praise of the Sheridan book was specially gratifying to Knight, as Ebsworth's grandfather Robert Fairbrother (p. 290) had been an intimate friend of the dramatist.

'THE GENTLEMAN'S MAGAZINE.'

Sylvanus

Urban.A correspondent in The Times on the 1st of July, 1907, called attention, in the following terms, to the fact that no mention had been made of Knight's "Sylvanus Urban" papers in The Gentleman's Magazine:—

"Few men were so well fitted to fill the historic chair of that writer as Mr. Knight; he combined the urbanity of a true man of letters with the sylvanity (if it may be called so) of a Yorkshireman who never allowed the traces of his origin to be whittled away by a long life in

London. . . . His minute intimacy with English and French literature of all dates was the more surprising in that he had enjoyed none of the visual facilities of education, and had acquired it entirely of his own initiative." On the purchase of The Gentleman's Magazine by Messrs. Chatto & Windus from Mr. Richard Gowing, who had edited it from 1874 to 1877, Knight became a contributor, and his articles appeared till within a very short time before his death. My friend Mr. Andrew Chatto has kindly shown me Knight's letters received by him during that period. These breathe all through the most kindly friendship and mutual regard. In a letter of the 17th of June, 1878, we find Knight ready to stand to his guns:—

"The paragraph about the Ministry you must read and judge about. I think it very important, but I cannot give up my authority. If you think it will cause an injury, I must stand it myself, as I will not bring others into a scrape. I am told it on good authority, and I think, if the newspapers don't get it, it is very important for us. . . . The few lines about my poor friend Sir Thomas Hardy might go also."

On the 12th of December, 1881, Knight writes:—

"Thanks for the 'Mary Stuart.' I have made a reference or two to it in 'Table Talk.'

'Joseph's

Coat."My object in writing is just to say that I have only to-day been able to finish 'Joseph's Coat.' It certainly is a strikingly powerful, ingenious, and original novel. It is sympathetic also. Once or twice in the book I smell artifice, my scent being particularly keen, as it ought to be; but I think the author one of the first

men of the day among novelists, and I paid him the compliment of shedding a few tears." The author was the late David Christie Murray.

THE LAUREATESHIP.

The Post

LaureateAnother publication of Messrs. Chatto & Windus to which

Knight occasionally contributed was The Idler. In 1895 the editor invited literary friends to contribute about two hundred words each on the selection of the next Poet Laureate. The following were those who complied : Sir Edwin Arnold, William Sharp, F. W. Robinson, Oscar Wilde, Coulson Kernahan, George Gissing, Norman Gale, Aaron Watson, Joseph Knight, I. Zangwill,

Grant Allen, George Manville Fenn, William Archer, John Strange Winter, Clement Scott, Barry Pain, Richard Le Gallienne, Clark Russell, G. B. Burgin, Bernard Shaw, John Davidson, and E. Nesbit. Each of the replies, which appeared in the April number of The Idler, was illustrated by a small portrait of the author by Louis Gunnis and Penryn Stanley. Knight thus stated his views:—

"The only man who could accept the Laureateship is Mr. Swinburne, Mr. Morris's politics putting him out of the running. I cannot think the gentlemen who supply us with a constant stream of verse—epic, lyric, dramatic, what not—possessing every attraction and quality except the essential, could seriously challenge the verdict of the ages upon their presumption. To do so would show a lack of the sense of humour, with which I hesitate to credit them.

Among our fledgeling bards, I find none who has, as yet, beaten out his music, or whose young wings have carried him near the higher peaks of Parnassus. There is abundance of excellent verse.

Almost everybody, nowadays, writes it. Poetry in these days is the blossom of most intelligent minds. Only when it becomes fruit is the world concerned with it. A single lyric in 'Atalanta' or 'Songs and Ballads' outweighs all the remaining verse issued in the United Kingdom. These opinions will, I know, if read, be

distasteful to many worthy gentlemen whom I greatly respect. It is not my fault. It was not I who wrote:—

Mediocribus esse poetis,

Non homines, non Di, non concessere columnæ.

As this is a popular magazine, I give Conington's translation:

But gods and men and booksellers agree

To place their ban on middling poetry.

If I were one of our minor bards, whom somebody approached on the subject of my claim to the Laureateship, I should look for the tongue in the cheek, or wonder whether I had incurred some concealed animosity. If Mr. Swinburne may not have the post, and I know there are some difficulties, let it be abolished. I do not wish to reduce the meagre recognition awarded to letters, but to fall from the height it has attained to its former level would be a dangerous experiment even for the Laureateship."

It would be pleasant to dwell upon the friendships formed by Knight, but these were so numerous that I find it impossible even to give the names of those by whom he was surrounded. It could truly be said of him:—

O well for him that finds a friend,

Or makes a friend, where'er he come;

And loves the world from end to end,

And wanders on from home to home.

Marston.At the Sunday evening gatherings at the house of his dearest of all friends , John Westland Marston, he met hosts of literary and interesting people, and for years Knight and his wife would dine at Marston's on Christmas Day. In later years, when Dr. Marston and his son Philip Bourke were alone left, they would dine at Knight's house and keep Christmas there. Mrs. Knight tells me: "I was very intimate with them all. There is not one of them left; even Dr. Garnett and his wife are gone. Miss Purnell was a special friend of mine, but she died soon after her brother."