thoughts in a larger mould. But the versatility with which the small forms are treated is a testimony to the magnitude of his creative faculty. The predominance of the small forms is explained by his earlier method of composing. Diligent and constant though he was in later years, in early life his way of working was fitful and inconstant. The compositions of this period seem as if forced out of him by sudden impulses of genius. As he subsequently says of his early works, 'the man and the musician in me were always trying to speak at the same time.' This must indeed be true of every artist; if the whole personality be not put into a work of art, it will be utterly worthless. But by those words Schumann means to say that as a youth he attempted to bring to light in musical form his inmost feelings with regard to his personal life-experiences. Under such circumstances it is but natural that they should contain much that was purely accidental, and inexplicable by the laws of art alone; but it is to this kind of source that they owe the magic freshness and originality with which they strike the hearer. The variations, op. 1, are an instance of this. The theme is formed of the following succession of notes:—

the names of which form the word 'Abegg.' Meta Abegg was the name of a beautiful young lady in Mannheim, whose acquaintance Schumann when a student had made at a ball. Playful symbolism of this kind is not unfrequent in him. To a certain extent it may be traced back to Sebastian Bach, who expressed his own name in a musical phrase; as Schumann afterwards did Gade's. (See 'Album für die Jugend, op. 68, no. 41). In the same way (Ges. Schriften, ii. 115) he expresses the woman's name 'Beda' in musical notes, and also in the 'Carnaval' tried to make those letters in his own name which stand as notes—s (es), c, h, a—into a musical phrase. But the idea really came from Jean Paul, who is very fond of tracing out such mystic connections. Schumann's op. 2 consists of a set of small pianoforte pieces in dance-form under the name of 'Papillons.' They were written partly at Heidelberg, partly in the first years of the Leipzig period which followed. No inner musical connection subsists between them. But Schumann felt the necessity of giving them a poetical connection, to satisfy his own feelings, if for nothing else, and for this purpose he adopted the[1] last chapter but one of Jean Paul's 'Flegeljahre,' where a masked ball is described at which the lovers Wina and Walt are guests, as a poetic background for the series. The several pieces of music may thus be intended to represent partly the different characters in the crowd of maskers, and partly the conversation of the lovers. The finale is written designedly with reference to this scene in Jean Paul, as is plain from the indication written above the notes found near the end—'The noise of the Carnival-night dies away. The church clock strikes six.' The strokes of the bell are actually audible, being represented by the A six times repeated. Then all is hushed, and the piece seems to vanish into thin air like a vision. In the finale there are several touches of humour. It begins with an old Volkslied, familiar to every household in Germany as the Grossvatertanz.[2]

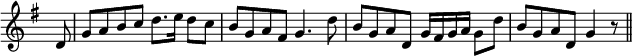

This is immediately followed by a fragment of; second Volkslied, in another tempo—

also old, and sung in Saxony in the early part of the 18th century. Sebastian Bach employed the whole of it, also in a humorous way, in his 'Bauercantate.'

Schumann, notwithstanding his intimate acquaintance with much of Bach's music, can scarcely have known of this, and so the fact of their both lighting on the theme is only an interesting coincidence.[3] In contrast to these two old-fashioned love-tunes is placed the soft and graceful melody of No. 1 of the 'Papillons,' which is afterwards worked contrapuntally with the 'Grossvatertanz.' The name 'Papillons' is not meant to indicate a light, fluttering character in the pieces, but rather refers to musical phases which, proceeding from various experiences of life, have attained the highest musical import, as the butterfly soars upwards out of the chrysalis. The design of the title-page in the first edition points towards some such meaning as this; and the explanation we have given corresponds with his usual method of composing at that time. There exists however no decisive account of it by the composer himself.

In a kind of connection with the 'Papillons' is the 'Carnaval,' op. 9. Here again Schumann has depicted the merriment of a masquerade in musical pictures and a third and somewhat similar essay of the same kind is his 'Faschingsschwank[4] aus Wien,' op. 26. The 'Carnaval' is a collection of small pieces, written one by one

- ↑ In a letter to his friend Henrietta Volgt, Schumann calls it the last chapter. This, although obviously a slip of the pen, has led several writers to wonder what grand or fanciful idea lurks behind the 'Papillons.'

- ↑ See Grossvatertanz, vol. i. p. 634a.

- ↑ Dehn's edition of the Bauercantate was published in 1839, 8 years after Schumann had composed the 'Papillons.'

- ↑ Fasching is a German word for the Carnival.