disadvantage of those who think no amount of study too great for the attainment of a thorough acquaintance with the arcana taught by the Great Masters.

We therefore counsel the Student to make a bold attack upon the difficulties we have pointed out; and, after having acquired the power of reading Clarinet Parts, to go on bravely to those written for the Corno di Bassetto; playing from the Scores of Mozart, Schubert, Beethoven, Weber, Mendelssohn, and Spohr, in the order in which we have here mentioned them; and, if need be, proceeding from these to the works of more modern writers, and even to Compositions scored for a Military Band. His progress, after the first steps are surmounted, will depend mainly upon the amount of experience he is able to gain, from careful listening to the performance of the Orchestral Works of Great Masters. The reproduction of an effect once heard is an easy matter, compared to the operation of imagining one suggested only by the appearance of the Score: and it is by carefully noting such effects, and remembering the combinations which produce them, that the Student strengthens his judgment, and eventually becomes an accomplished Player from Score.

SCORING. The term Scoring is applied to the process of displaying the various Parts of an Orchestral Composition upon a single page, in order that the whole may be read at a glance. [See Score.]

To the copyist, this process is a purely mechanical operation. He scores an Overture, or a Symphony, by transcribing its separate Parts, one above the other, in the order indicated in one of the schemes shown at pp. 430–433; and, in so doing, has to contend with no difficulty whatever, beyond that of counting his bars correctly.

To the Composer, the Scoring of an orchestral work is a much more serious matter. He does not, as a general rule, begin the process, until he has, in great measure, determined upon the effects he intends to produce, and the office he intends to assign to his principal Instruments.[1] Having settled these points satisfactorily, he usually writes out the more important Parts at once, without waiting to fill in those that are of less consequence; and, when the plan of the whole is thus sketched out, he proceeds to supply the minor details, at his leisure, frequently with considerable modifications of his original intention.

The autograph Scores of the great Masters exhibit this process, in all its successive phases. For instance, in the original Score of 'La Sonambula,' the Recitative which precedes 'Tutto è sciolto' is introduced by a long passage for two Valve Trumpets, which Bellini afterwards entirely crossed out.

But, it is from unfinished Scores that we derive the most valuable instruction on this important point. In the unfinished Score of Mozart's 'Requiem,' known as the Urschrift, and now preserved in the Imperial Library at Vienna, we find the Composer beginning to Score his several Movements by writing out the Vocal Parts in full, with the Basso continuo, for the Organ and Basses; the Parts for the other Instruments being only filled in where the Voices are silent, or, for the purpose of indicating, at the beginning of a Movement, some special figure in the Accompaniment, intended to be fully written out at a future time.

No less interesting and instructive is the unfinished Score of Schubert's Seventh Symphony, in E, now in the possession of the Editor of this Dictionary, and which is fully described under the head of Sketch.

These two invaluable MSS. would serve to give us a very clear idea of the method of working pursued by the Great Masters, even if they stood alone: but, fortunately, their testimony is corroborated by that of many similar documents, in the handwriting of Beethoven, and other Classical Composers, who, notwithstanding their individual peculiarities, all proceeded upon very nearly the same general principles. The study of these precious records puts us in possession of secrets that we could learn by no other means; and, by carefully comparing them with complete Scores, by the same great writers, we may gain a far deeper insight into the mysteries of Scoring than any amount of oral instruction could possibly convey.

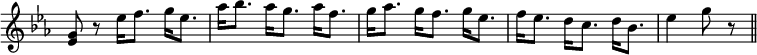

SCOTCH SNAP or CATCH is the name given to the reverse of the ordinary dotted note which has a short note after it—in the snap the short note comes first and is followed by the long one. It is a characteristic of the slow Strathspey reel rather than of Scotish vocal music, though as Burns and others wrote songs to some of these dance-tunes, it is not infrequently found in connection with words. 'Green grow the rashes,' 'Roy's wife,' 'Whistle o'er the lave o't,' and above all, Hook's excellent imitation of the Scotish style, 'Within a mile of Edinburgh,' contain examples of the snap. It was in great favour with many of the Italian composers of last century, for Dr. Burney—who seems to have invented the name—says in his account of the Italian Opera in London, in 1748, that there was at this time too much of the 'Scots catch or cutting short of the first of two notes in a melody.' He blames Cocchi, Perez and Jomelli 'all three masters concerned in the opera Vologeso' for being lavish of the snap. An example of it will be found in the Musette of Handel's Organ Concerto in G minor (1739); he also uses it occasionally in his vocal music.

SCOTCH SYMPHONY, THE. Mendelssohn's own name for his A minor Symphony (op.

- ↑ See Orchestration, vol. ii. pp. 567–573.