(7) The most difficult note of the Scale to answer is the Supertonic. It is frequently necessary to reply to this by the Dominant; and when the Tonic is immediately followed by the Supertonic, in the Subject, it is often expedient to reiterate, in the Answer, a note, which, in the original idea, was represented by two distinct Intervals; or, on the other hand, to answer, by two different Intervals, a note which, in the Subject, was struck twice. The best safeguard is careful attention to Rule 3, neglect of which will always throw the whole Fugue out of gear.

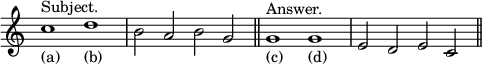

(a) Tonic, answered by Dominant, at (c).

(b) Supertonic, answered by Dominant, at (d).

Simple as are the foregoing Rules, great judgment is necessary in applying them. Of all the qualities needed in a good Tonal Subject, that of suggesting a natural and logical Tonal Answer is the most indispensable. But some Subjects are so difficult to manage that nothing but the insight of genius can make the connection between the two sufficiently obvious to ensure its recognition. The Answer is nothing more than the pure Subject, presented under another aspect: and, unless its effect shall exactly correspond with that produced by the Subject itself, it is a bad answer, and the Fugue in which it appears a bad Fugue. A painter may introduce into his picture two horses, one crossing the foreground, exactly in front of the spectator, and the other in such a position that its figure can only be truly represented by much foreshortening. An ignorant observer might believe that the proportions of the two animals were entirely different; but they are not. True, their actual measurements differ; yet, if they be correctly drawn, we shall recognise them as a well-matched pair. The Subject and its Answer offer a parallel case. Their measurement (by Intervals) is different, because they are placed in a different aspect; yet, they must be so arranged as to produce an exactly similar effect. We have shown the principle upon which the arrangement is based to be simply that of answering the Tonic by the Dominant, and the Dominant by the Tonic, whenever these two notes follow each other in direct succession; with the farther proviso, that all passages of Melody formed upon the Tonic Harmony shall be represented by passages formed upon the Dominant Harmony, and vice versâ. Still, great difficulties arise, when the two characteristic notes do not succeed each other directly, or, when the Harmonies are not indicated with inevitable clearness. The Subject of Handel's Chorus, 'Tremble, guilt,' shows how the whole swing of the Answer sometimes depends on the change of a single note. In this case, a perfectly natural reply is produced, by making the Answer proceed to its second note by the ascent of a Minor Third, instead of a Minor Second, as in the Subject—i.e. by observing Rule 4, with regard to the Sixth of the Tonic.

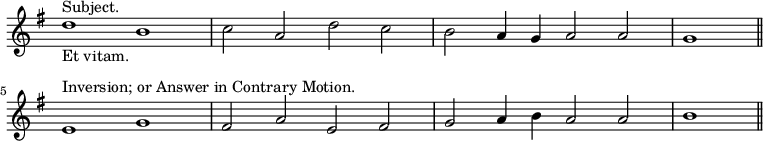

The Great Masters frequently answered their Subjects in Contrary Motion, giving rise to an apparently new Theme, described as the Inverted Subject (Inversio; Rivolta, Rivolzimento; Umkehrung). This device is usually employed to keep up the interest of the Composition, after the Subject has been discussed in its original form: but some Masters bring in the Inverted Answer at once. This was a favourite device with Handel, whose Inverted Answers are so natural, as to be easily mistaken for regular ones. The following example is from Cherubini's 'Credo' already mentioned.

Another method of answering is by Diminution, in which each note in the Answer is made half the length of that in the Subject. This, when cleverly done, produces the effect of a new Subject, and adds immensely to the spirit of the Fugue; as in Bach's Fugue in E, No. 33 of the XLVIII, bars 26–30; in the Fugue in C♯ minor, No. 27 of the same set; and, most especially, in Handel's Chorus, 'Let all the Angels.'

![{ \relative e'' { \key d \major \time 4/4

<< { r2^"Subject." r4 e | a e fis e8 d\noBeam | cis } \\

{ r2 r8 d,_"Answer, by diminution" a'\noBeam e |

fis e16 d cis8 b16 cis d8[ fis] gis8. gis16\noBeam | a2 } >> } }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/6/0/60ca5il2qf27qa0q1dxlf9cpw2s1mhu/60ca5il2.png)

Allied to this, though in the opposite direction, is a highly effective form of treatment by Augmentation, in which each note in the Answer is twice the length of that in the Subject, or in Double Augmentation, four times its length. The object of this is, to give weight to massive passages, in which the lengthened notes produce the effect of a Canto fermo. See Bach's Fugue

- ↑ The 'Answer' here might with equal propriety be considered as the 'Subject'; in which case the answer would be by Augmentation.