Mode II. Transposed

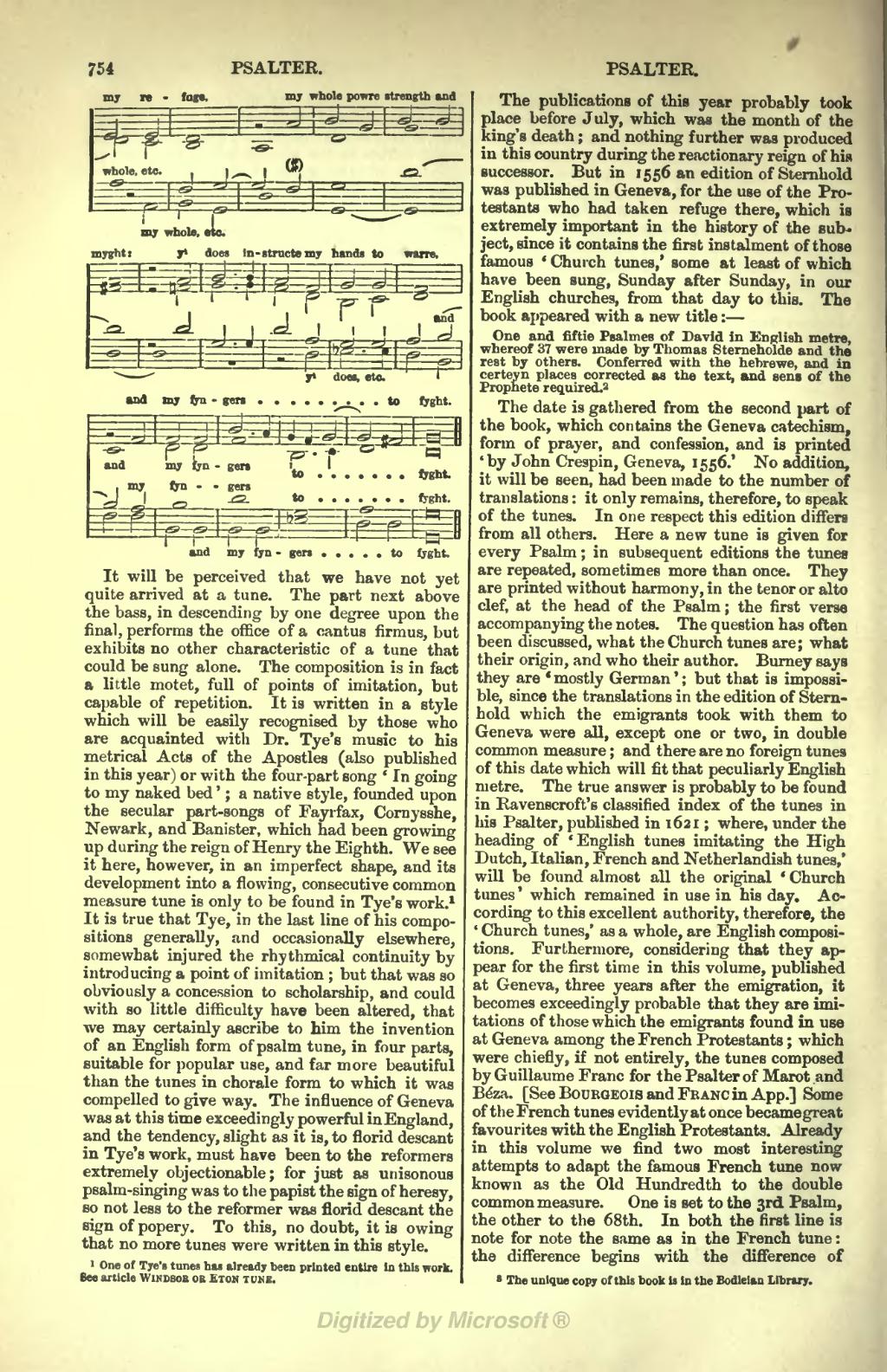

It will be perceived that we have not yet quite arrived at a tune. The part next above the bass, in descending by one degree upon the final, performs the office of a cantus firmus, but exhibits no other characteristic of a tune that could be sung alone. The composition is in fact a little motet, full of points of imitation, but capable of repetition. It is written in a style which will be easily recognised by those who are acquainted with Dr. Tye's music to his metrical Acts of the Apostles (also published in this year) or with the four-part song 'In going to my naked bed'; a native style, founded upon the secular part-songs of Fayrfax, Cornysshe, Newark, and Banister, which had been growing up during the reign of Henry the Eighth. We see it here, however, in an imperfect shape, and its development into a flowing, consecutive common measure tune is only to be found in Tye's work.[1] It is true that Tye, in the last line of his compositions generally, and occasionally elsewhere, somewhat injured the rhythmical continuity by introducing a point of imitation; but that was so obviously a concession to scholarship, and could with so little difficulty have been altered, that we may certainly ascribe to him the invention of an English form of psalm tune, in four parts, suitable for popular use, and far more beautiful than the tunes in chorale form to which it was compelled to give way. The influence of Geneva was at this time exceedingly powerful in England, and the tendency, slight as it is, to florid descant in Tye's work, must have been to the reformers extremely objectionable; for just as unisonous psalm-singing was to the papist the sign of heresy, so not less to the reformer was florid descant the sign of popery. To this, no doubt, it is owing that no more tunes were written in this style.

The publications of this year probably took place before July, which was the month of the king's death; and nothing further was produced in this country during the reactionary reign of his successor. But in 1556 an edition of Sternhold was published in Geneva, for the use of the Protestants who had taken refuge there, which is extremely important in the history of the subject, since it contains the first instalment of those famous 'Church tunes,' some at least of which have been sung, Sunday after Sunday, in our English churches, from that day to this. The book appeared with a new title:—

One and fiftie Psalmes of David in English metre, whereof 37 were made by Thomas Sterneholde and the rest by others. Conferred with the hebrewe, and in certeyn places corrected as the text, and sens of the Prophete required.[2]

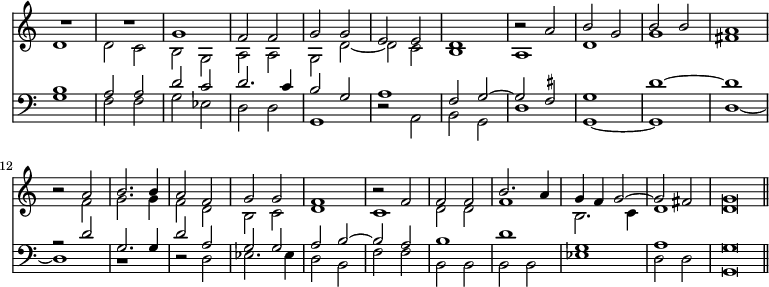

The date is gathered from the second part of the book, which contains the Geneva catechism, form of prayer, and confession, and is printed 'by John Crespin, Geneva, 1556.' No addition, it will be seen, had been made to the number of translations: it only remains, therefore, to speak of the tunes. In one respect this edition differs from all others. Here a new tune is given for every Psalm; in subsequent editions the tunes are repeated, sometimes more than once. They are printed without harmony, in the tenor or alto clef, at the head of the Psalm; the first verse accompanying the notes. The question has often been discussed, what the Church tunes are; what their origin, and who their author. Burney says they are 'mostly German'; but that is impossible, since the translations in the edition of Sternhold which the emigrants took with them to Geneva were all, except one or two, in double common measure; and there are no foreign tunes of this date which will fit that peculiarly English metre. The true answer is probably to be found in Ravenscroft's classified index of the tunes in his Psalter, published in 1621; where, under the heading of 'English tunes imitating the High Dutch, Italian, French and Netherlandish tunes,' will be found almost all the original 'Church tunes' which remained in use in his day. According to this excellent authority, therefore, the 'Church tunes,' as a whole, are English compositions. Furthermore, considering that they appear for the first time in this volume, published at Geneva, three years after the emigration, it becomes exceedingly probable that they are imitations of those which the emigrants found in use at Geneva among the French Protestants; which were chiefly, if not entirely, the tunes composed by Guillaume Franc for the Psalter of Marot and Béza. [See Bourgeois and Franc in App.] Some of the French tunes evidently at once became great favourites with the English Protestants. Already in this volume we find two most interesting attempts to adapt the famous French tune now known as the Old Hundredth to the double common measure. One is set to the 3rd Psalm, the other to the 68th. In both the first line is note for note the same as in the French tune: the difference begins with the difference of

- ↑ One of Tye's tunes has already been printed entire in this work. See article Windsor or Eton Tune.

- ↑ The unique copy of this book is in the Bodleian Library.