"Oh, bother the old books!"

And as if to bother them, though more likely to break their backs, Lance Penwith closed two with a sharp clap, rose from his seat at the table, and then, holding one flat in each hand, he walked round behind his cousin, who was bent over another, with his elbows on the study-table, a finger in each ear, and his eyes shut as if to keep in the passage he was committing to memory. But the next moment he had started up, hurting his knees, and stood glaring angrily at Lance, who was roaring with laughter.

For the hearty-looking sunburned boy had passed behind his fellow-student's chair with the intention of putting his books on one of the shelves, but seeing his opportunity, a grin of enjoyment lit up his face, and taking a step back, he stood just at his cousin's back, and brought the two books he carried together, cymbal fashion, but with all his might, and so close to the reader's head that the air was stirred and the sharp crack made him spring up in alarm.

"What did you do that for?"

"To wake you up, Alfy. There, put 'em away now, and let's go down to the cliff."

"And leave my lessons half done?—Don't you do that again. You won't be happy till I've given you a sound thrashing."

"Shouldn't be happy then," said Lance, with a laugh; "and besides, you couldn't do it, Alfy, my lad, without I lay down to let you."

"What! I couldn't?"

"Not you. Haven't got strength enough. Jolly old molly-coddle, why don't you come out and bathe and climb and fish?"

"And hang about the dirty old pilchard houses and among the drying hake, and mix with the rough old smugglers and wreckers."

"How do you know they're smugglers and wreckers?"

"Everybody says they are, and uncle would be terribly angry if I told him all I know about your goings on."

"Tell him, then: I don't care. Father doesn't want me to spend all my time with my nose in a book, my eyes shut, and my ears corked up with fingers."

"Uncle wants you to know what Mr. Grimston teaches us."

"Course he does. Well, I know my bits."

"You don't: you can't. You haven't been at work an hour."

"Yes, I have; we sat down at ten, and it's a quarter past eleven, and I know everything by heart. Now, then, you listen."

"Go on, then," cried the other.

"Not likely. I've done. Come on and let's do something. The rain's all gone off and it's lovely out."

"There, I knew you didn't," cried the other. "You can't have learned it all. And look here, if you do that again I shall certainly report it to uncle."

"Very well, report away, sneaky. Now then, will you come? We'll get Old Poltree's boat and make Hezz come and row." The student reseated himself, frowning, and bent over his book again.

"Look here," cried his cousin, "I'll give you one more chance. Will you come?"

No answer.

"One more chance. Will you come?"

"Will you leave off interrupting me?" cried the other furiously.

"Certainly, sir. Very sorry, sir. Hope you will enjoy yourself, sir. Poor old Alf! He'll want specs soon."

Then pretending great alarm, the speaker darted out into the hall, and thrust his head through a door on the right, which he half opened, and stood looking in at a slightly grey-haired lady who was bending over her work.

"Going out, mother," he said.

The lady looked up and smiled pleasantly.

"Don't be late for dinner, my dear. Two o'clock punctually, mind."

"Oh, I shall be back," said the boy, laughing.

"And don't do anything risky by the cliff."

"Oh no, I'll mind."

The boy closed the door and crossed the hall, just as a shadow darkened the porch, and a tall, bluff-looking man entered.

"Hullo, you, sir!" he cried; "how is it you are not at your studies?—Going out?"

"Yes, father; down to the shore a bit. Done lessons."

"Why don't you take your cousin with you?"

"Won't come, father. I did try."

It was only about half a mile to the cliff, where a few fishermen's cottages stood on shelves of the mighty granite walls which looked as if they had been built up of blocks by the old Cornish ogres, weeded out by the celebrated Jack the Giant-killer; and here Lance made his way to where in front of one long whitewashed granite cot, perched a hundred feet above the shore, there was a long protecting rail formed of old spars planted close to the edge of the cliff, just where a tiny river discharged itself into the sea. This opened sufficiently to form a little harbour for half-a-dozen fishing luggers, the rocks running out sufficiently to act as a breakwater and keep off the huge billows which at times came rolling in from the south-west, so that on one side of the cliffs lay piled up a slope of wave-washed and rounded boulders, many as big as great Cheshire cheeses, while on the other, where the luggers lay, there were pebbles and sand.

Upon this rail four men were leaning with folded arms, apparently doing nothing but stare out at the bright, clear sea; but every eye was keenly on the look-out for one of those dark-cloud, shadow-like appearances on the surface which to them meant money and provisions.

But there was no sign of fish breaking the surface of the water, and as Lance approached he had a good view of four immense pairs of very thick flannel trousers, whose bottoms were tucked into as many huge boots, which, instead of being drawn well up their owners' thighs, hung in folds about their ankles, and glittered in the sunshine, where they were well specked with bright fish scales.

Higher up Lance looked upon four pairs of very short braces, hitched over big bone buttons, and holding the aforesaid trousers close up under their wearers' armpits. The rest of the costume consisted of caps, home-made, and of fur formerly worn by unfortunate seals which had come too near a boat instead of seeking safety in one of the wave-washed caves round the point.

"Hi! Old Poltree!" shouted Lance, as he drew near, "where's Hezz?"

The broadest man present raised his head a little, screwed it round, and unfolding his arms, set one at liberty to give three thrusts downward of a hand which was of the same colour as all that could be seen of a very hairy face—mahogany.

"Thankye," shouted Lance, turning off to the left, and the big man folded his arms again and looked seaward, the others not having stirred.

Lance's turn to the left led him to a steep descent all zigzag—a way to the shore that a stranger would have attacked like a bear and gone down backwards; but Lance was no stranger, and the precipitous nature of the way did not deter him, for he descended in a series of jumps from stone to stone, till he finished with a drop of about ten or a dozen feet into a bed of sand lying at the mouth of a wave-scooped hollow, from which came strange moans and squeaks, the latter painfully shrill, the former deepening at times into a roar.

The said stranger would have imagined that a person had fallen from the cliff and was lying somewhere below, badly broken and wanting help; but there was nothing the matter. It was only Hezz, or more commonly "Hezzerer," in three syllables, and he had been busy at work putting a patch on the bottom of a clumsy upturned boat which, as he put it, "lived in the cave," and he was now daubing his new patch with hot tar from a little threelegged iron kettle held in his left hand.

But this does not account for the groans and squeaks. These were produced from the youth's throat. In fact, Hezz was singing over his work, though it did not sound very musical at the time, for something was broken; but it was only Hezz's voice, and it was only the previous night that Old Poltree, his father, had said to Billy Poltree, another of the big fisherman's offspring, "Yo' never know wheer to have him now, my son: one minute he's hoarse as squire's Devon bull, and next he's letting go like the pig at feeding time."

At the sound of the dull thuds made by Lance's feet in the sand, Hezz Poltree whisked himself round and held his tar-kettle and brush out like a pair of balances to make him turn, and showed a good-looking young mahogany face—that is to say, it was paler than his father's, and not so ruddy and polished.

"Hullo, Master—Lance," he said, widening his mouth and showing his white teeth, joining in the laughter as the visitor threw himself down on the sand and roared.

"Whisked himself round and held his tar-kettle and brush out like a pair of balances."

"I can't help it, Master—Lance."

"Try again," cried the new-comer, wiping the tears from his eyes.

"I do try," growled the boy, beginning once more in a deep bass, and then ending in a treble squeak. "There's somethin' got loose in my voice. 'Tarn't my fault. S'pose it's a sort o' cold."

"Never mind, gruff un. But I didn't know the boat was being mended. I wanted to go out fishing, and the pitch isn't dry."

"That don't matter," growled Hezz, setting down his kettle and brush, and catching up a couple of handfuls of dry sand, which he dashed over the shiny tar. Come on."

Lance came on in the way of helping to turn the clumsy boat over on its keel; then it was spun round so as to present its bows to the sea; a block was placed underneath, another a little way off, and the two boys skilfully ran it down the steep sandy slope till it was half afloat, when they left it while they went back to the natural boat-house for the oars, hitcher, and tackle.

"Got any bait?" said Lance.

"Heaps," came in a growl. Then in a squeak—"Thought you'd come down, so I got some wums—lugs and rags, and there's four broken pilchards in the maund, and a couple o' dozen sand-eels in the coorge out yonder by the buoy."

"Are there any bass off the point?"

"Few. Billy saw some playing there 'smorning, but p'raps they won't take."

"Never mind; let's try," said Lance eagerly. "Look sharp; I must be back in time for dinner."

"Lots o' time," growled Hezz, as he loaded himself up with the big basket, into which he had tumbled the coarse brown lines and receptacles of bait, including a scaly piece of board with four damaged pilchards laid upon it and a sharp knife stuck in the middle. "You carry the oars and boat-hook," came in a squeak.

They hurried down to the boat, and were brought back to the knowledge that four pairs of eyes were watching them from a hundred feet overhead, by Old Poltree roaring out as if addressing some one a mile at sea—

"You stopped that gashly leak proper, my son?"

" Iss, father," cried Hezz, in a shrill squeak, as he dumped down his load.

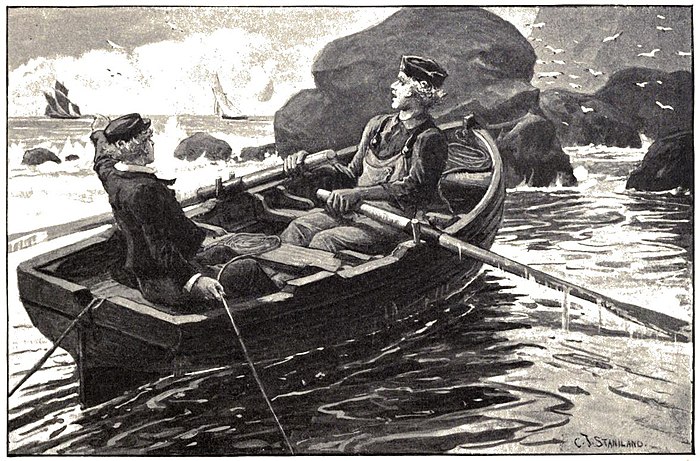

Lance thrust in the oars and hitcher and sprang in, after giving the boat a thrust; and as a little wave came in and floated her, Hezz ran her out a bit farther and sprang in too, thrust an oar over the stern, and sculled the craft out, fish-tail fashion, to where a black keg did duty for a buoy. Here he kept the boat's head while Lance leaned over the side to unhitch a piece of line and draw a spindle-shaped wicker basket along the side to the stern, where he made it fast to a ring bolt, the movement sending a score or so of eely-looking silvery fish gliding over one another and flashing by the thin osiers of which the basket was formed.

Then each seized an oar and pulled right away to get round the rocky buttress which was continued outward in a few detached rocks, that stood up boldly, to grow smaller farther out, and farther, till only showing as submerged reefs over which the sea just creamed and foamed.

It was out here that the tide ran swiftly, a favourite spot for the bass to play, and as they approached the familiar spot Lance handed his oar to his sturdy companion, while he took one of the lines, laid the hook and lead ready, and then drew the coorge in, opened a wicker trap-door in the top, inserted his hand, closed the lid again, and with deft fingers hooked the silvery writhing fish, popped it overboard, and let the line run out with the tide, while Hezz kept the boat carefully, as nearly as he could, in one place.

"There they are, Master Lance," he cried. "Be on the look-out; they'll take that bait pretty sharp perhaps."

The lad was quite right, for hardly five minutes had elapsed before there was a snatch at the line, and something was hooked.

"Got him!" cried Lance, whose face was glowing with excitement. "Oh, why didn't Alfy come? I say, Hezz, he's a whopper. He does pull. Shall I let him run?" "Gahn! no. Haul him in fast as you can, 'fore he gets off."

The tackle was coarse and strong, and there was no scientific playing attempted. It was plain, straightforward pully-hauly work, and in a very short time the transparent water astern seemed to be cut into flashing streaks by something silvery which was drawn in hand over hand, till, just as Lance was leaning over to get his fingers close to the end of the snood where the hook was tied, the water was splashed up into his face, and he sat up with a cry of disappointment, seeing only a streak of silver flashing in the sunshine, for the fish had gone.

"Never mind: bait again," squeaked Hezz.

"Bait again," cried Lance, imitating him. "What! with that hook? Look at it. Nearly straightened out. I wish you wouldn't have such nasty soft-roed things. Why, that was a fifteen pounder."

"Take another hook, Master Lance. Look sharp; look at 'em playing."

Lance put on a fresh hook, baited again, and sent the sand-eel gliding off along the rushing tide, which played among the rocks like a mill-stream, and waited excitedly for another snatch, but waited in, vain.

"Don't pull," he said at last; "let the boat run out a bit."

Hezz obeyed, cleverly managing so that the boat glided slowly after the bait in the direction of the broken water where the shoal of bass could be seen feeding; but they got no nearer, for so sure as the boat went farther from land, so did the fish, and in spite of fresh and tempting baits being tried there was no seizure made.

"That there one as got away has told all the others to look out," said Hezz, with a chuckle. "You won't get another bite."

"Stuff and nonsense! Just as if fish could talk! Let's go out farther."

The boat glided on, with the current growing less swift, and at last Lance drew in his line, sat down, and between them they rowed slowly in against the sharp current.

"It's no good now," said Hezz. "Let's go along yonder by the mouth of the caves, and try for a pollack among the rocks. If we don't get one we may ketch a rock-fish or two."

"Or a conger in one of the deep holes."

"Nay, you won't ketch none o' them till it's getting dark."

"Dark enough in the holes," said Lance.

"Very well; you try."

So the boat was rowed out of the sharp current, and then away towards the west under the cliffs, and about a hundred yards from the shore, where the tide ran slowly. Here Lance gave up his oar and began to fish again, trying first one and then another kind of bait, but with no greater result than catching a grey gurnard—"tub" Hezz called it—and soon after a couple of gaily-coloured wrasse, not worth having.

"Oh, this is miserable work!" cried the boy, drawing in his line and covering a large hook with half a pilchard. "Pull a little farther along, and I'll throw out in that dark quiet part. There'll be a conger there, I know."

Hezz uttered a croak, and his eyes said plainly, "No conger there "; but he rowed to the spot, which was where a rock rose up out of the water like a little island, on which a dusky cormorant which had been fishing sat drying its wet wings, paying no heed to the approaching boat till it was some twenty yards away, when the bird took flight and went off close to the surface.

"Now put her just in yonder," said Lance, "and be as gentle as you can, so as to keep her there without splashing."

Hezz obeyed cleverly enough; and his companion, after

"Rev'nue cutter," said Hezz shortly.

seeing that the line lay in rings free from obstruction, sent the heavy sinker and bait right away to where the water looked blackest, making Hezz chuckle loudly.

"What are you laughing at?"

"You: telling me to be so quiet, and sending the lead in with a splash like that."

"Don't matter; it's only at the top. The fish deep down won't notice it. Look! it is deep too," for the line went on running out as the lead descended, and Lance seated himself to wait, with a self-satisfied look upon his countenance.

"I like fishing in the still water," he said. "You see if I don't soon get hold of something big."

"P'raps," said Hezz; "but I never caught anything here."

"Ah, you don't know everything. I say, what's that vessel out yonder?"

"Chasse-marée," said Hezz, shading his eyes to look at the long three-masted lugger with a display of interest.

"No, no; the one with all the white sails set."

"Rev'nue cutter," said Hezz shortly; and proof of his words was given the next minute, for there was a white puff of smoke seen to dart out from her bows, and a dull thud echoed from the cliff.

"Why, she's after that long lugger. She's a smuggler," cried Lance excitedly. "Is there going to be a fight?"

"Na-a-a-a-y!" growled Hezz. "She's only fishing."

"How do you know? She's a smuggler, and there'll be a fight. Let's row out and see."

But in obedience to the summons the long low vessel glided slowly round till her brown sails began to shiver and flap, and as the boys watched they saw the cutter run pretty close up, and a small boat was lowered and rowed across.

"They're French, and cowards," cried Lance, who was deeply interested. "They've surrendered without striking a blow."

"Arn't got nothing to strike blows with," croaked Hezz sulkily. " Didn't I tell you she was a fishingboat?"

"Oh, yes; but I know what fishing-boats catch sometimes, Master Hezz," said Lance, laughing, his companion looking at him curiously the while—"brandy snappers, 'bacco biters, and lace-fins, Hezz. But they're French cowards, or they'd have made a run of it. I say, they'll make her a prize, and take her into port. Where will they take her—Plymouth or Falmouth?"

"Nowheres. They'll let her go."

The lads sat watching till all at once in the distance they saw the little boat row back, and the sails of the chasse-marée began to fill.

"Who's right now?" said Hezz, laughing.

"I am. They've put a prize crew on board."

"What! out of that little boat?" squeaked Hezz.

"That they haven't. There was five in her when she put put off, and there's five in her now."

"You can't see at this distance."

"Can't I? That I can, quite plain."

"That's upset all my fishing," said Lance, "and it's getting on for dinner-time. Oh, what bad luck I do have!"

"You ketch lots sometimes, and you did nearly get a fine bass to-day. That was a good twelve-pounder."

"Twelve? Fifteen," said Lance, preparing to haul in his line.

"P'raps," said Hezz. "Going to try any more?"

"No; I mustn't be late for—— Oh, look here! I've got one on."

For the line was tight, and as Lance began to haul, it was against a heavy persistent drag.

"Lead caught in the rocks," croaked Hezz contemptuously.

"Oh, is it! Look here! It's coming up."

"Weed, then," squeaked Hezz.

"'Tisn't," cried Lance; "I know by the heavy, steady pull. It's a big conger."

"No congers there."

"How do you know?"

"And if there were they wouldn't bite at this time of day."

"You mind your own business," cried Lance excitedly.

"It's a thumping big one, and he isn't awake yet to his being hooked. He's coming, and he'll begin to make a rush directly to get in his hole. You begin rowing, and get him right out away from the rocks."

Hezz did as he was told, but only made two or three strokes and then stopped, for his companion had to give line.

"Slower," said Lance, panting, as he held on again.

"Wait till he makes a rush. I say, did you bring the big gaff hook?"

"No; but that line'll hold any conger you can catch, and I've got the little chopper in the locker when he comes on board. But that isn't a conger."

"'Tis, I tell you. I can feel him trying to get back.—What is it, then?"

"Weed," croaked Hezz in his deep bass.

"You're a weed! It's a big conger, and he has got his tail round a rock or in a hole."

"Let him go, then."

"What? Why he'd shuffle back into his hole, and I should lose him. Wait till he gets a bit tired and gives way a bit."

"Let go, and if it's a conger he'll slack the line and come swimming up to see what's the matter. But you've only hooked a weed."

"Ha! ha!" laughed Lance. "You're a clever one, Hezz. Look, he's coming up quite steady;" and the boy drew in a couple of yards of line.

"It arn't a conger, or he'd begin to cut about now and shake his head to get riddy of the hook."

"Then it's some other big fish. Think it's a shark."

"No. What would a shark be doing there?"

"I dunno; but he's coming up. I say, put down the oars."

Hezz nodded, laid in his oars, and stood close behind his companion, gradually growing as excited for a minute or so, and then grinning.

"It arn't no fish," he said.

"It is, I tell you," cried Lance, as he kept up a steady haul, the boat having yielded till it was exactly over the line.

"I never see a fish take it so quiet as that," continued Hezz.

"It's only till he sees us, and then he'll make a desperate rush to get away."

"I'll be ready for him," said Hezz, laughing softly, as he gently rested the handle of the boat-hook on the side, thrusting it out towards the tightened line, which still came slowly in, though the strain threatened to make it part. "Hope it will be good to eat, Master Lance."

"I know what it is," cried the boy, in a low hoarse voice. "It's one of those great cuttles, the same as were washed on shore after last year's storm. It will come up all of a lump, with its feelers and suckers twisted round the line."

A sudden change came over Hezz. Instead of grinning, his face turned preternaturally solemn, and taking his right hand from the boat-hook he thrust it into his pocket, drew out a big jack-knife, to open it by seizing the blade in his teeth.

"That's right," whispered Lance, husky now with the excitement; "but don't use the knife if you can get a good hold with the hook. Look, look, here it comes! Oh, it is a monster!"

"A vigorous cut divided the fishing-line."

The boy had been steadily hauling till he had brought his capture nearly to the surface, and he now caught sight of what seemed to be its curved and rounded body.

"Now, Hezz—quick! down with the hook. Get a good hold at once. Snatch, lad, snatch!"

But at the crucial moment, when the dark back of the monster slowly rolled up to the surface, Hezz dropped the boat-hook, leaned over the side, hindering his companion's view, and plunged his knife-armed hand down under water.

The next moment there was a slight jar which ran from Lance's fingers right up his arms, the tension ceased, and a yard or two of the stout fishing-line flew up in the holder's face.

For, as if to save his companion from some danger, Hezz had reached down as low as he could, and with a vigorous cut divided the fishing-line, so that the dark round body sank down again like a shadow, leaving the two lads gazing fiercely at each other.

"Oh, I say!" cried Lance. "Only to think of that! Why, Hezz, it's—"

"Never you mind what it is," said the boy roughly.

"And you knew it was, then?"

"Swears I didn't," said the boy fiercely. "Think I should have let you fish there if I had knowed?"

"Why, there must have been a whole string of 'em tied together on a line and sunk there."

"You don't know nothing of the sort," growled Hezz. "You didn't see."

"I saw one; and another coming like a shadow."

"No, you didn't."

"Yes, I did—brandy kegs—smuggled. Here, I'll hail the cutter."

"No, you don't," said Hezz fiercely; and as he stood with the knife in his hand he looked threatening. "They couldn't hear you if you did."

"Then I'll make signals."

"No, you won't. I shan't let you, and you wouldn't be such a sneak, Master Lance."

"It isn't the act of a sneak."

"Yes, it is. Your cousin would, but you wouldn't get poor men into trouble."

That hit hard, and Lance hesitated.

"Why, it must be your father's and your brother's doing. And just under our noses too! Oh, what a disgraceful shame! There, Hezz, I've done with you."

"I didn't know about it, Master Lance."

"You must have known."

"Wish I may die if I did. There!"

"Take the oars, Hezz," said Lance coldly.

"But, Master Lance"

"Take the oars," said Lance sternly. " I want to go home."

"To tell Squire Penwith what you've seen? O Master Lance! you don't know what you're going to do."

"No," said Lance sternly, as the lad took the oars and began to row back, "I don't."

"You make me feel as if I'd sooner kill you than you should do this. It means having my poor father took up and sent out of the country, and p'raps he didn't know the kegs was hid like that."

"Go on rowing, I tell you," cried Lance sharply, "make haste. Pull! do you hear? Pull!"

Hezz uttered a low sound something like a gulp, and dragged away at the oars with all his might till he ran the boat on to the sands, where Lance was perfectly aware, though he would not look up, that the four big fishermen were still leaning over the rail and looking out to sea, and he expected to hear a cheery question as to sport as he hurried up over the sands and began to climb the zigzag.

But no hail came, for the men's eyes were bent upon the revenue cutter, a mile away, watching every movement of that and the chasse-marée.

At least so thought Lance Penwith as he hurried home, pondering upon his cousin's words, and asking himself whether he was not doing wrong by associating with these fisher-folk on the cliff.

"I must tell father," he said to himself. "I ought to tell him," he said; and then he began thinking of what it meant, the severe punishment of pretty well every man in the cluster of cottages, some being sent to prison, the younger men to serve in King George's men-of-war; and ever since he could remember, they had all been to him the kindest friends.

CHAPTER II

" I can't help it," said Lance to himself, after a weary sleepless night; " I don't feel as if I could go and tell tales. I'm not sure; and if I was wrong, and these men were punished for what they did not do, I should never be happy again."

Lance had made up his mind that he would have no more to do with the people down by the cliff, for he felt now that they were not honest. But there was a bitter feeling of disappointment in coming to this resolve; for it had been so pleasant to get away from the refinements of home with its choice cookery, plate, glass, and fine linen, to the boisterous welcome he always had at Old Poltree's neat cottage. How delicious the baked hake was, and how luscious the conger pie!—though they were as nothing to the split and grilled fish he caught himself; and Hezz's mother was always ready to cook for the two boys.

And now it was all over; but still he might go and climb to the steep edge, from whence he could look down on the whitewashed cottages, the busy harbour, and the boats.

This he did, and grew quite excited as he saw that the revenue cutter was lying off the point, a couple of miles out, as if watching the place.

"Poor old Hezz!" he said to himself bitterly, "I hope they will not take him."

Then incongruously enough he smiled as he thought of the boy's breaking voice.

"They'd laugh at him if they heard him croak and squeak as he does now, and perhaps let him off because he's only a boy. But it would be horrible for the other men.

"Why, father's a magistrate too," said the lad suddenly, "and he'd be with the others who punished them for smuggling if it was found out. Oh, I can't go and tell what I know! It would be horrid."

Lance lay there upon the warm cliff for some time thinking, and then he started and looked down, wondering at what was to him quite a marvel. For there, moving slowly, about a hundred feet below him, was his cousin, threading his way amongst the masses of granite tangled with brambles, in a part where there was no path, nothing more than a faint track or two made by the grazing sheep, and it seemed unaccountable.

"What's he doing there?" muttered Lance. "He must be looking for me. Well, let him look. I don't want him. If I shout to him he'll only come and begin to preach at me in his pompous way. When I'm in a good temper it only makes me laugh; but I'm in a bad temper now, and if he begins I shall feel as if I must punch his head."

So Lance lay and watched, making unpleasant remarks the while, all of a derisive nature. He watched till Alfred had disappeared beyond the chaos of rocks which had fallen from above, and at last he strolled back home, forgetting all about his cousin till he took his place at the luncheon-table, and felt surprised to see him there, looking quite cool and as if he had passed the morning reading in the shade.

There was another surprise for Lance before he left the table, the squire letting fall the announcement that Captain Barry was going to dine there at six o'clock that evening. "So you boys will have to put on your best manners."

"Who's Captain Barry, father?"

"To speak correctly, he is Lieutenant Barry, my boy, and is in command of the revenue cutter lying on and off. They are giving us all a good hunt up, for he tells me that there has been a great deal of smuggling carried on along this coast; but I told him the only smuggling about here is the smuggling of fish."

Lance felt that the tips of his ears turned hot, and thought that they must be red. He knew that this was the opportunity for telling all he had found out, but somehow the words would not come.

The officer was rowed ashore from the cutter that evening, and the squire had walked down to the tiny harbour, with the two boys, to meet him, and find him a frank, pleasant, middle-aged man, who, for some reason, had never been promoted.

He shook hands, and Lance turned scarlet, and then glanced shoreward, to see that Hezz was busy turning the clumsy boat half inside the cavern, and that the big trousers and boots were up on the shelf, while the men inside them seemed to be gazing out to sea in search of a coming shoal.

The officer was very pleasant and frank during his stay. He chatted with the boys and asked them if they would like to go to sea; but somehow he found Lance dull and glum, and the boy's father bantered him that night after the visitor had gone back to the cutter.

CHAPTER III

A week had glided by, and fishing was in full progress below the cliff. Hezz and his people had enclosed a small shoal of mackerel in their seine, and at another time Lance would have been in the thick of the business, revelling in seeing the line of corks drawn in closer and closer till the shoal was dashing about seeking for a way of escape, before the tuck net was brought to bear, and the arrowy wave and ripple-marked fish were ladled out in baskets.

Lance had watched the movements of the cutter anxiously while she stayed off the point; but one fine day she had glided away west with all sail set to the light breeze, and the boy breathed more freely.

Then the days passed and nothing seemed to happen, except that when Lance went along the high cliffs, climbing from place to place till he settled himself down in some snug rift where he could scan the sea and note what was going on in the cove below, to see if there was any sign of smuggling, he found that his cousin came cautiously along no less than three times, and the boy laughed to himself from his hiding-place.

"He's watching me to see if I go down and join Hezz. How can any one be such a sneak?"

Lance often mused after this fashion as the days slipped by; but he kept away from the people down by the cliff, in spite of a wistful look or two he caught from Hezz, who came up to the house several times to sell fish.

"No," Lance said firmly, "I haven't told tales; but I won't have anything to do with smugglers."

One fine afternoon soon after dinner Lance saw his cousin go into the study and take down a book, rest his head on his hands, and begin to read.

Lance had followed him to propose that they should go inland and have a ramble in the woods, but his cousin's action checked him.

"It's of no use," he said; "he wouldn't come."

So the lad went off till he reached one of his favourite look-outs, just by a rift overgrown with brambles, where, when the tide was up, the whispering and washing of water could be heard, showing that one of the many caverns and cracks along the bold coast ran in a great way.

"Wish I knew which of them belonged to this," he had more than once said; and upon this particular occasion as he seated himself he began listening to the strange whispering sounds.

"I meant to have tried to find this out," he said, "along with Hezz. Why, I did say something about it once, and he only laughed and said it was a land-spring. Well, I can't get the boat now."

Somehow the place had a strange fascination for him that day, and after looking about a bit he picked up a piece of mossy granite as big as his head and pitched it among the bramble growth and ferns just where the whispering washing sound could be faintly heard.

To his surprise there was the fluttering of wings, and a jackdaw flew out and away.

"Nest there," he muttered; but his thoughts were divided by hearing the stone he had pitched down strike heavily, sending up a hollow sound; and directly after it struck again more loudly, and all was still.

He was in the act of rising to examine the spot, but he sank down directly, ducking his head behind a great tuft of ragwort.

"Well, he is a sneak," he muttered.

He sat close, and Alfred passed about twenty yards below, going on cautiously away to the right, and passing out of sight.

Lance sighed, rose, and looked away to the west; but there was no sign of his cousin, so he walked back home.

The night came on soft and calm, and after sitting reading a bit, and going over some translation ready for the vicar next day, Lance looked up, to see that he was alone, so putting away his books he strolled out on to the big sloping lawn to where he could see the sea; but it looked quite dark and forbidding, and the stars were half hidden by a haze. Still it was very pleasant out there, and after a time he turned to look back at the house with its light or two in the windows of the ground-floor, while everything else looked black, till all at once a little window high up in the centre gable of the old Elizabethan place shone out brightly with a keen steady bluish light which lasted while he could have counted twenty, and then all was blacker than ever.

"Why, it's a firework," said Lance to himself. "It must be Alf."

He had hardly thought this when the light shone out again, burned brightly for a time, and once more went out, leaving the boy wondering, till it once again blazed out sharply, and left all blacker than ever.

Lance's mind was just as black and dark, for he could make nothing of it. Alfred was not likely to be letting off fireworks. What could it mean?

Coming to the conclusion that his cousin had been amusing himself in some way or another connected with chemistry, he stood thinking for a minute and then went in, to find the object of his thoughts sitting by his aunt's side talking quietly, while the squire seemed engrossed in a book.

"Well, perhaps you had better," said Mrs. Penwith. "There's nothing like bed for a bad sick headache."

The boy sighed, said good-night, and went up to his room.

"He had too long a walk to-day," said Mrs. Penwith, "and the sun upset him. By the way, Lance, your cousin complains about your being given to avoiding him. Do, pray, put aside all sulkiness and be more brotherly."

"Why, it is Alf, mother, who never will come out with me."

"There, there, say no more about it," said Mrs. Penwith gently. "You know I wish you to be brotherly, so do try."

Lance felt too much aggrieved to say anything, and sat in moody silence till it was bed-time, when he said "good-night" and went to his own room, thinking the while about those lights.

There he lay, thinking and listening for above an hour, during which he heard the various sounds in the house of the servants shutting up and going to bed, and soon after his father and mother's room door closed, and he settled down to go to sleep.

He might as well have settled down to keep awake, for he turned and twisted, and got out of bed to drink water, and got in again. Then he turned the pillow and tried that. Next he threw off the quilt because he was too hot. And so on, and so on, till he sat up to try and face the question which haunted his brain: What did those lights in the little upper window mean?

"It's of no use," said the boy at last. "I shall never go to sleep till I know." He sprang out of bed and dressed himself, and then stood thinking. Did he dare go up in the dark to that little room in the roof and see whether he could find out anything?

Yes; and while the exaltation of brain was upon him, he softly opened his door, went out into the broad passage, and along it to the end where the little oak staircase led up to the three attic-like places in the three gables, rooms that were only used for lumber and stores.

The boy's heart beat heavily as he went up in his stockings, and twice over when a board cracked he was

"A signal! came the next moment in answer."

ready to rush back to his room; but he forced himself into going on, and stood at last at the centre door of the three, feeling that if he hesitated now he should never do it.

So pushing the door it yielded, and he nearly darted back, for there was a peculiar sulphury smell in the dark room.

But Lance had made fireworks in his time, especially blue lights, and the smell was just the same as that, and he no longer felt scared, for the thought flashed across his brain that some one had burned some pieces of blue light there, and if such were the case there would be something on the window-sill on which they had been burned.

He stepped boldly in, and there, sure enough, he found what he expected— a little piece of sheet-iron about half the size of a slate.

But what for?

A signal! came the next moment in answer; and wildly excited now, he stepped back across the room, descended the stairs and went to the door of his cousin's chamber, tried the door softly, found it yield, and entered. The bed was empty, and quite cold.

CHAPTER IV

A few moments elapsed, and then it was Lance who had turned quite cold. For his brain was wonderfully active now, as he seemed to grasp as facts that his cousin had not been watching him on the cliff, but had found out something about the smugglers and was watching them. Then, too, he recalled how friendly he had been with the captain of the revenue cutter, and how they had talked together.

This, then, was the meaning of the signal: Alf had found out something—of course; a long low chasse-marée had been lying off that day, he recalled, and the signal lights had been meant for the cutter, which must have crept in at dusk, and for aught he knew the King's men might be landing, in answer to the signals, to catch the fishermen and smugglers in the very act of landing a cargo.

Right or wrong, Lance paused to think no more. It was a time to act and try and warn his old friends. How could Alf be such a sneak?

Quickly and silently he stepped out and back to his own room, put on his boots, opened the window and lowered himself down the heavy trellis, reached the lawn, and ran to get to the zigzag and reach Old Poltree's cottage on the ledge.

"I'll tell Hezz," he said to himself—"just say the King's men are out, and then get back."

It is easier to make plans than to carry them out.

When Lance reached the long whitewashed cottage, meaning to knock till Hezz came to his window, he was caught by a strong hand, wrenched round, and a hoarse voice said in a whisper——

"Who's this?"

"I—Lance, Mother Poltree. I came to tell you I'm afraid the King's men are coming to-night."

"Whish!" she said, as she clapped another great hand over his mouth. "Who told tales—you?"

"No, no, I wouldn't."

"Whish! they're coming," she cried, as she stood listening. "They came after you."

"I—I didn't know," whispered Lance, as he made out steps descending the zigzag, showing that he was only just in time, for whoever it was had been close behind.

"This way," said the old woman sternly, and all thought of retreat was cut off, for she held the boy's arm firmly and hurried him to the end of the cottage and across the patch of garden.

"For there below him, lit up by a few lanterns, he could make out the hull of a great lugger."

At one time they were ascending as if to climb to the cliff top, then down, and up again, till at the end of a few hundred yards a rift was reached, down which the old woman hurried the lad, uttering a peculiar hissing sound the while, which quite changed the aspect of the scene which had unfolded itself to Lance's astonished gaze. For there below him, lit up by a few lanterns, he could make out the hull of a great lugger, lying in the jaws of the rift down which they were hurrying, while men were wading waist-deep to and fro—those going out to the lugger's side empty-handed, these coming bearing bales and kegs, which they carried to a low rocky archway, so low that it must have been covered when the tide was up, while now they stooped and passed in their loads to other hands, which seized them and bore them away.

At the warning hiss uttered by the old fisherwoman the work ceased, and as a man, evidently the captain, swung himself down into the water, Old Poltree, his sons, and another man crept out from beneath the rugged archway.

Few words were spoken. The captain of the lugger gave an order or two, splashed through the water with his men, and climbed on board, where the lanterns were extinguished, hitchers and sweeps thrust forth on either side, and the English fishermen waded out to put their shoulders to the stern of the boat and help to thrust her out into the open water.

Their help did not last, for the water deepened rapidly and the great lugger was well on the move, and unless the boats of the revenue cutter were waiting for them her safety was assured. The danger was from the shore for those who had been breaking the laws.

"This your doing, young gen'leman?" growled Old Poltree fiercely, approaching Lance.

"No!" cried the boy eagerly.

"Nay, no lies, my lad. The French skipper saw three lights, and he thought it was our doing. You did it to bring 'em on."

"Indeed, no!" cried Lance. "I saw them too, and as soon as I guessed what it meant I ran down to warn you; didn't I, Mother Poltree?"

"Iss, my son.—You're wrong, old man, it was t'other youngster. I told you he was after no good."

"Then it warn't you, Master Lance?" squeaked a voice. "Hooroar!"

"You hold your row, Hezzerer," growled his father; and then quickly, "Look, they've found the way down. Someun's showing 'em with a light."

His gruff voice was evidently heard, for from where the dull yellow light of a horn lantern shone at the top of the gash in the massive cliff a stern voice shouted—

"Surrender, in the King's name, or we fire."

"Fire away, then," muttered Old Poltree. "Tide'll be up soon. In with you, my lads. In with you, missus, for you can't get back now."

"Come along, Master Lance," whispered Hezz, who had crept close to his old companion.

"No, no!" cried Lance, aghast. "I'm not coming with you; I must go back."

"Nay, my son; you can't now," growled Old Poltree. "In with you;" and he dragged the boy down into the water and gave him a thrust, while as Lance indignantly raised his head again to rush back, he saw by the light of a single lantern held by one of the men that he was in a spacious water-floored cavern which evidently extended for some distance; but what interested him most in his awkward position was the sight of the big old man on one side of the exit, his eldest son on the other, each armed with a piece of broken oar, ready to defend the natural door against all comers.

"Right away with that light," growled the old man, and its bearer splashed through the water farther and farther away.

"Come on, Master Lance," whispered Hezz, catching him by the arm.

"Let go," cried the boy angrily. "I will not be taken with you."

"Nay, you shan't be, young Master Lance," whispered the old woman. "My Hezz'll show you the way out, while my old man keeps the sailors back till the tide's up and they can't get in."

"Yes, that's right, Master Lance," whispered Hezz, and the boy unwillingly followed the lantern-bearer till at the end of a hundred yards the water had ceased and they were walking over the dry rocky bottom of the rapidly-contracting cave, where Lance noticed that a heap of casks and bales had been hurriedly piled up.

And now from behind him there came the shouts of men and the noise of heavy blows and splashing; but neither of those with him seemed in the least disturbed, Hezz even chuckling and saying—

"It's all right, old mother; father won't let no one pass. I say, we shall have to haul you up."

"'Fraid so, my son," said the old woman. "I'm too heavy to clamber now."

A wild feeling of excitement pervaded Lance all this time, mingled with indignation at what he mentally called his cousin's treachery. But he felt better at the thought that he was to escape, for the idea of being captured with the smugglers was horrible.

And now his attention was taken up by the movements of Hezz, who, while the man held the lantern up, took a coil of rope from where it rested on a big stone, thrust his head and one arm through it, and began to climb up a rugged narrow crack at the end of the cavern—climbing as if he had been up there before, and soon disappearing from their view.

But they could hear him plainly enough, his boots grating on the rock, and his heavy breathing coming whispering down for some minutes before all was still, but only for the silence to be broken by a curious rustling sound, and Lance caught sight of the rope uncoiling as it fell.

"Up with you," said the man with the lantern, and Old Poltree's second son seized the rope, and by its help climbed up in much less time than his brother; while Lance longed for his turn to come that he might hurry away, but felt an unwillingness to go before the woman with them was saved.

"Come on," was whispered, and the other man gave the lantern to Mother Poltree, while the shouting and splashing at the cavern entrance grew fainter.

In a very short time there was another summons from above, but at this moment they were joined by big Billy Poltree.

"All right, mother," he said. "Mouth's pretty well covered. I'll go next, so as to help pull you up. They can't get in now."

The man seized the rope, and as he disappeared in the dark crack Lance thought of the consequences if the King's men came now and seized them, so that he started round guiltily when he heard a sound behind him; but it was only the old fisherman.

"Hullo, young squire," he said; "not gone? Well, I'll go next, and then I can help with you both."

With a display of agility that was wonderful in so old and heavy a man, he directly after seized the rope and climbed up, leaving Lance with the old woman, who stood silently holding the lantern and gazing back.

"Tide's right over the mouth now," she said.

"Is it?" replied Lance; and anxiously, "Pray tell them all, Mother Poltree, that I didn't betray them. I wouldn't do such a thing."

"Needn't tell 'em, my son," said the old woman. " No one would believe it of you. But it's a bad job for us if they catch my folk. It means sending 'em across the seas. Now, then, up with you, quick; and then I'll dowse the light."

"No, you first," said Lance.

"Nay, my son, you. Don't waste time. They ought to be making for the moors by now."

Lance seized the rope and climbed actively, finding plenty of foothold, and soon after reaching the open air in the spot which he felt sure was where he had heard the splashing and thrown down the stone.

"Now quick, boys," whispered Old Poltree. "She's got the rope fast round her I can feel. Haul steady; give her time; and then we must make for the hills. They won't hurt the women."

"Quick! this way; I can hear them," cried a familiar voice out of the darkness, and from two ways there was a rush of footsteps and a scrambling sound.

Lance made a dart to dash away, but some one flung his arms about him, lifted him from the ground, and rolled with him over and over amongst the furze and brambles.

"Keep still," whispered a voice in his ear; and he lay quiet, for it was Hezz listening to the sounds of struggling and pursuit till they died away, and then he rose.

"Don't say naught to me, Master Lance—I'm too bad; but you keep close to me and I'll show you how to get back to the big house without the King's men ketching of you. Quick! here's one of 'em."

This on hearing a hoarse panting, but a voice whispered—

"Hezz!"

"You, mother! Got up?"

"Yes, my son, with all the skin off my hands. Have they got away?"

"I think so, mother. What are you going to do?"

"Get home to tell the girls. And you?"

"See Master Lance safe, and then get hid somewheres till they're all gone. I shall be all right, and they won't hurt you. Come on, Master Lance."

No more was said, Lance having his work to do in climbing after his companion, who led him by what by daylight he would have considered to be an impossible path; but it ended at the stone wall which bordered the cliff part of the home grounds, and when he began to thank his companion he was gone, only a faint rustling as of a rabbit telling of which way.

Ten minutes later Lance had climbed back to his bedroom window, closed it, and after regaining his breath he stole out into the passage to make his way to his cousin's room.

But all was silent there. Alf had not returned.

Lance crept back to his own bedroom, undressed, and lay down to listen for his cousin's return, undecided as to what he should do.

Nature decided it for him, sending him off fast asleep, wearied out by his exertions; but before dawn his door was opened and a light step crossed the floor and paused by his bedside, a low ejaculation as of astonishment being heard, and then the steps were directed to the door, which was softly closed.

CHAPTER V

Lance made his appearance at breakfast the next morning rather late, and as he entered the room, wondering whether his father knew of the events of the night, he saw at a glance that everything had come out, for the squire was speaking angrily to Alfred, who stood before him with his face cut and scratched, and a great piece of sticking-plaister across one hand.

"Oh," he cried, "there you are, sir!"

"You may have considered it your duty, sir, still I think it was very dishonourable of Captain Barry to make use of you as his spy without a word to me; but of course he would know that I should not countenance such a thing. It is quite time you went away from home, sir; so prepare yourself, and you will go to one of the big grammar schools as soon as you can make arrangements. That will do, sir: I do not want to hear another word. I am a magistrate, and I want to uphold the law, but all this business seems to me cowardly and bad.—Oh," he cried, "there you are, sir!"

"Yes, father," said Lance, drawing a deep breath.

"You know, I suppose, that the King's men have found a nest of smugglers here, under my very nose?"

"Yes, father."

"And you were in bed all night, of course?"

"No, father. I found out by accident that Alf was going to betray them."

"Betray, eh? And pray how?"

"He burnt blue lights at the top window as a signal to bring the French lugger ashore."

"Indeed! Worse and worse," cried the squire angrily. "And you, sir—pray what did you do?"

"Went and told Old Poltree and his lads to look out."

"You did, eh?"

"Yes, father."

"And pray why?"

"Because, father," said the boy boldly, "I thought it was such a shame."

"You hear this, my dear?" said the squire, turning to Mrs. Penwith.

"Yes, love," said that lady, looking at her son with tearful eyes.

"And I am a magistrate, and my son behaves like this! 'Pon my word, this is supporting the law with a vengeance. But here's breakfast. I'll think about it, and see what I ought to do."

But the squire was so taken up with a visit from the commander of the cutter, which had made its appearance off the point that morning, and going down and seeing the clearing out of the cave, in which there was a grand haul for the sailors, that he apparently forgot to speak to his son. He had no prisoners brought before him, for the smugglers had all escaped; and when Mrs. Penwith told him with a troubled face that their two boys had met at the bottom of the garden, quarrelled, and fought terribly, he only said—

"Which whipped?"

"Lance, my dear. Alfred is terribly knocked about."

"Oh," said the squire, and that was all.

A month passed away before Hezz was seen back at the cottage, and oddly enough that was the very day on which Alfred said good-bye to the place and was driven off with his box, his cousin going with him to the cross roads six miles away, where he was to meet the Plymouth waggon; and it was on Lance's return that he strolled to the cliff to look down at the cottage, and saw Hezz below on the sands once more tarring his boat.

CHAPTER VI

[{sc|The}} cliff and the little harbour beneath looked as beautiful as ever; but there was an element of sadness about the place whenever Lance went down to see Hezz, for he was pretty sure to encounter one or other of the sad-faced women busy in some way or another.

There was no playtime for Hezz, whose big, open, boyish face had grown old and anxious-looking; but he always had a smile and a look of welcome for Lance whenever he went down, and rushed off to get the boat ready for a fishing trip somewhere or another.

But these were not pleasure excursions, for as soon as the boat was pushed off the two lads tugged at the oars or set the sail to run off to some well-known fishing ground, where they worked away in a grim earnest way to get together a good maund of fish, a part of which was always sold up at the "big house," and at a good price too.

As for the women, they worked hard in their patches of garden, or went out in couples to bait and lay the lobster pots, or set the trammel nets, sometimes successfully, more often to come back empty; but somehow they managed to live and toil on patiently with a kind of hopeful feeling that one day things would mend.

"Ever see any of the French smugglers now, Hezz?" said Lance to him one day.

The boy's eyes flashed, and he knit his brows.

"No," he said, in a deep growl, for there had been no squeak in his voice since the night of the fight; the last boyish sound broke right away in that struggle, and he seemed to have suddenly developed into a man. "No," he said, "nor don't want to. If it hadn't been for them the old man and Billy and t'others would ha' been at home, 'stead o' wandering the wide world over."

"Have you any idea where they are, Hezz?"

The lad looked at him fiercely.

"Want to get 'em took?" he growled.

"Of course," said Lance, smiling. "Just the sort of thing I should do."

"Well, I didn't know," said Hezz.

"Yes, you did," cried Lance. "Want me to kick you for telling a lie?"

"Well, you're a young gent, and young gents do such things. Look at your cousin."

"Now, just you apologise for what you said, or I'll pitch into you, Hezz," cried Lance. "Now then: is that the sort of thing I should do if I knew where the old man and the rest were?"

"No," said Hezz, grinning, "not you."

"Then just you apologise at once."

"Beg your pardon, grant your grace, wish I may die if I do so any more. That do?"

"Yes, that'll do. Now tell me where they are, just to show me you do trust me."

"Tell you in a minute, Master Lance," cried the lad earnestly, "but I don't know a bit. We did hear from a Falmouth boat as some un' had sin 'em up Middlesbro' way after the herrin'; but that's all, and p'raps they're all drownded. I say, I'll tell you something, though. What d'yer think my old woman said about your mother?"

"I don't know. What did she say?"

"Said she was just a hangel, and she didn't know what she should ha' done all through the stormy time if it hadn't been for her."

"Oh, bother! I didn't want to hear about that," said Lance hurriedly.

"But you ought to hear, and so I telled you. I say, what's gone of your cousin?"

"Never you mind. What is it to you?" said Lance roughly. "You don't want to see him again."

"Nay, I don't want to see him, Master Lance, 'cause I might feel tempted like; and I don't want to run again' him, it might make me feel mad."

"Ah, well, you won't feel mad, Hezz, for he is never likely to come back here again. He's at a big school place, and going to college soon."

"Well, I'm glad he isn't likely to come; not as I should fly out at him, but Billy's wife right down hates him, and there's the other women do too, for getting their lads sent away. You see they've the little uns to keep; and Billy's wife says to me, on'y las' Sunday as we come back along the cliffs from church with the little gal, 'Hezz,' she says, and she burst out crying, 'it's like being a lone widow with her man drowned in a storm, and it's cruel, cruel hard to bear.' "

"And what did you say, Hezz?"

"Nothin', Master Lance. Couldn't say nothing. Made me feel choky and as if my voice was goin' to break agen; so I give her luttle gal a pigaback home, and that seemed to do Billy's wife good. Hah, I should like to see our old man home agen, for it's hard work to comfort mother sometimes when I come back without my fish, and she shakes her head at me and says, 'Ah, if your father had been here!'"

"Poor old lady!" said Lance.

"You see, it's when she's hungry, Master Lance. She don't mean it, 'cause she knows well enough there was times and times when the old man come back with an empty maund; but then you see she'd got him, and now it's no fish and no him nayther.—No, I won't, Master Lance. I didn't say all that for you to be givin' me money agen."

"Well, I know that, stupid. It's my money, and I shall spend it how I like. It isn't to buy anything for you, but for you to give to the old woman."

"Nay, I won't take it. If you want to give it her, give it yourself. I arn't a beggar.—Yes, I am, Master Lance—about the hungriest beggar I ever see."

"You take that half-crown and give it to Mother Poltree, or I'll never speak to you again."

"No, I won't. You give it her."

"I can't, Hezz; she makes so much fuss about it, and kisses me, and then cries. Seems to do more harm than good."

"I won't take it," growled Hezz, "but you may shove the gashly thing in my pocket if you like.—Thankye for her, Master Lance; it arn't for me. And look here, mind, I've got it all chalked down in strokes behind my bedroom door, and me and Billy and the old man'll pay it all back agen some day."

"All right, Hezz," said Lance merrily. "You shall; so it's all so much saved up, and when you do pay it we'll buy a new boat, regular clinker-built, copper-fastened, and sail and mast."

"That we will, Master Lance," cried the lad eagerly.

"One as can sail too, so's we can hold a rope astern and offer to give t'others a tow. I say, think the old man will ever come back?"

"I hope so, Hezz."

"Ay, that's what I do—hopes. Sent over the sea, I s'pose, if they did."

"Oh, don't talk about it, Hezz!" cried Lance bitterly. "Why didn't they be content with getting a living with the fish?"

Hezz made no reply, but trudged off to the long whitewashed cottage on the cliff, where as Lance watched he saw Mother Poltree come out and Hezz hand her the big silver coin with King George's head on one side.

The result was that the brawny old woman threw her apron over her face, tore it down again and looked down below, caught sight of the giver, and began to descend.

But Lance was too quick for her: he took flight and ran below the cliff, scrambling over the rocks, for it was low tide, and had a toilsome climb up a dangerous part so as to get back home.

CHAPTER VII

It was one bright spring morning after getting well on with his Latin reading with the vicar, that Lance thought he would go down to the cliff and see what luck Hezz had had with the trammel overnight.

Suddenly he stopped short and stood staring down at the cliff shelf, hardly believing it was true, for there below him in a row stood four great pairs of stiff flannel trousers in four pairs of heavy fisherman's boots, just as if the men's wives had put them out in the sunshine against the old wooden rail to sweeten and dry out some of the damp salt, in case their wearers should come back.

But Lance Penwith had lived there too long to be deceived by such a sight as that, and uttering a cry of amazement he began trying to break his neck by a heavy fall before he arrived safely on the broad shelf, to yell out, "Ship ahoy!"

Then, and then only, did the biggest and broadest pair of trousers begin to move, and a great shaggy head turned to show a dark mahogany face fringed with stiff white hair.

"Come back!" shouted Lance; "and you too, Billy; and you two."

"Master Lahnce, lad!" cried the old man, making a grab at the boy's hand with one of his huge paws, clapping the other upon it, and working it up and down slowly as he said, "The old 'ooman's told me all about it, and I says, humble and thankful like, God bless yer!"

"And so says all on us," chorused his companions.

"That's right, my sons; that's right," growled the old man.

"But you've come back," cried Lance, trying in vain to free his hand, for the others wanted to shake it, and Billy Poltree had to be content with the left, while the other men ornamented the boy with fleshly epaulettes in the shape of a hand apiece on the shoulders.

"Ay, my lad, we've come back," said Old Poltree solemnly, "for it's weary months and months as we four has been in desert lands up the eastern parts and up the norrard coasties; but it's allus been with a long lookout for the native land as we felt as we must see once more afore we died. We bore it all as long as we could, and then we said we'd get home and see our wives and bairns, and then they might take us and send us away across the main, for it arn't been living, has it, my sons?"

There was a tremendous No! and plenty of answering of eagerly put questions before Lance could get away and run panting up to where the squire and his mother were sitting at home.

"They've come back—they've come back!" he shouted, and then he stood as if struck dumb at the thought of what he had done—raced off to tell the only magistrate for miles round that the fugitive smugglers had returned as if to give themselves up.

"Master Lahnce, lad!" cried the old man, making a grab at the boy's hand.

A few questions followed, and Mrs. Penwith sat gazing anxiously from husband to son and back again, for the same thought occurred to her as had flashed upon her boy—"What will he say?" But it was something quite different from anything they expected.

"Come back, Lance? Yes, you've come back, and the dinner is getting cold. Come along."

Lance stared. But his father said something more before they left the table.

"So those smuggling rascals have come back? Well, I always expected they would. A nice long lesson they've had. Well, knowing what I do, I shall not take any steps unless I am obliged by pressure from Falmouth. Then, of course, I must. They are your friends, Lance, not mine; and I suppose they have quite given up smuggling."

"Yes, father," cried the boy; "Old Poltree told me, with tears in his eyes, that if he had known what was to come of it he would never have touched keg or bale. They'll never smuggle again."

"Let them prove it while they have a chance, my boy; it may tell in their favour when they are arrested and sent for trial."

"But this is a very out-of-the-way place," he said afterwards to Mrs. Penwith, "and I don't think any one will trouble them, for the matter is almost forgotten now."

"But ought you to——"

"Where's that boy?" said the squire, frowning.

Lance had rushed off again to tell his friends on the cliff how his father had taken their return.

![]()

This work was published before January 1, 1929, and is in the public domain worldwide because the author died at least 100 years ago.

Public domainPublic domainfalsefalse