It has been suggested that this work be split into multiple pages. If you'd like to help, please review the style guidelines and help pages. |

HYDRAULICS (Gr. ὕδωρ, water, and αὐλός, a pipe), the branch of engineering science which deals with the practical applications of the laws of hydromechanics.

§ 1. Properties of Fluids.—The fluids to which the laws of practical hydraulics relate are substances the parts of which possess very great mobility, or which offer a very small resistance to distortion independently of inertia. Under the general heading Hydromechanics a fluid is defined to be a substance which yields continually to the slightest tangential stress, and hence in a fluid at rest there can be no tangential stress. But, further, in fluids such as water, air, steam, &c., to which the present division of the article relates, the tangential stresses that are called into action between contiguous portions during distortion or change of figure are always small compared with the weight, inertia, pressure, &c., which produce the visible motions it is the object of hydraulics to estimate. On the other hand, while a fluid passes easily from one form to another, it opposes considerable resistance to change of volume.

It is easily deduced from the absence or smallness of the tangential stress that contiguous portions of fluid act on each other with a pressure which is exactly or very nearly normal to the interface which separates them. The stress must be a pressure, not a tension, or the parts would separate. Further, at any point in a fluid the pressure in all directions must be the same; or, in other words, the pressure on any small element of surface is independent of the orientation of the surface.

§ 2. Fluids are divided into liquids, or incompressible fluids, and gases, or compressible fluids. Very great changes of pressure change the volume of liquids only by a small amount, and if the pressure on them is reduced to zero they do not sensibly dilate. In gases or compressible fluids the volume alters sensibly for small changes of pressure, and if the pressure is indefinitely diminished they dilate without limit.

In ordinary hydraulics, liquids are treated as absolutely incompressible. In dealing with gases the changes of volume which accompany changes of pressure must be taken into account.

§ 3. Viscous fluids are those in which change of form under a continued stress proceeds gradually and increases indefinitely. A very viscous fluid opposes great resistance to change of form in a short time, and yet may be deformed considerably by a small stress acting for a long period. A block of pitch is more easily splintered than indented by a hammer, but under the action of the mere weight of its parts acting for a long enough time it flattens out and flows like a liquid.

|

| Fig. 1. |

All actual fluids are viscous. They oppose a resistance to the relative motion of their parts. This resistance diminishes with the velocity of the relative motion, and becomes zero in a fluid the parts of which are relatively at rest. When the relative motion of different parts of a fluid is small, the viscosity may be neglected without introducing important errors. On the other hand, where there is considerable relative motion, the viscosity may be expected to have an influence too great to be neglected.

Measurement of Viscosity. Coefficient of Viscosity.—Suppose the plane ab, fig. 1 of area ω, to move with the velocity V relatively to the surface cd and parallel to it. Let the space between be filled with liquid. The layers of liquid in contact with ab and cd adhere to them. The intermediate layers all offering an equal resistance to shearing or distortion, the rectangle of fluid abcd will take the form of the parallelogram a′b′cd. Further, the resistance to the motion of ab may be expressed in the form

where is a coefficient the nature of which remains to be determined.

If we suppose the liquid between ab and cd divided into layers as shown in fig. 2, it will be clear that the stress R acts, at each dividing face, forwards in the direction of motion if we consider the upper layer, backwards if we consider the lower layer. Now suppose the original thickness of the layer T increased to nT; if the bounding plane in its new position has the velocity nV, the shearing at each dividing face will be exactly the same as before, and the resistance must therefore be the same. Hence,

But equations (1) and (2) may both be expressed in one equation if and are replaced by a constant varying inversely as the thickness of the layer. Putting

or, for an indefinitely thin layer,

an expression first proposed by L. M. H. Navier. The coefficient μ is termed the coefficient of viscosity.

According to J. Clerk Maxwell, the value of μ for air at θ° Fahr. in pounds, when the velocities are expressed in feet per second, is

that is, the coefficient of viscosity is proportional to the absolute temperature and independent of the pressure.

The value of μ for water at 77° Fahr. is, according to H. von Helmholtz and G. Piotrowski,

the units being the same as before. For water μ decreases rapidly with increase of temperature.

|

| Fig. 2. |

§ 4. When a fluid flows in a very regular manner, as for instance when it flows in a capillary tube, the velocities vary gradually at any moment from one point of the fluid to a neighbouring point. The layer adjacent to the sides of the tube adheres to it and is at rest. The layers more interior than this slide on each other. But the resistance developed by these regular movements is very small. If in large pipes and open channels there were a similar regularity of movement, the neighbouring filaments would acquire, especially near the sides, very great relative velocities. V. J. Boussinesq has shown that the central filament in a semicircular canal of 1 metre radius, and inclined at a slope of only 0.0001, would have a velocity of 187 metres per second,[2] the layer next the boundary remaining at rest. But before such a difference of velocity can arise, the motion of the fluid becomes much more complicated. Volumes of fluid are detached continually from the boundaries, and, revolving, form eddies traversing the fluid in all directions, and sliding with finite relative velocities against those surrounding them. These slidings develop resistances incomparably greater than the viscous resistance due to movements varying continuously from point to point. The movements which produce the phenomena commonly ascribed to fluid friction must be regarded as rapidly or even suddenly varying from one point to another. The internal resistances to the motion of the fluid do not depend merely on the general velocities of translation at different points of the fluid (or what Boussinesq terms the mean local velocities), but rather on the intensity at each point of the eddying agitation. The problems of hydraulics are therefore much more complicated than problems in which a regular motion of the fluid is assumed, hindered by the viscosity of the fluid.

Relation of Pressure, Density, and Temperature of Liquids

§ 5. Units of Volume.—In practical calculations the cubic foot and gallon are largely used, and in metric countries the litre and cubic metre (= 1000 litres). The imperial gallon is now exclusively used in England, but the United States have retained the old English wine gallon.

| 1 cub. ft. | = 6·236 imp. gallons | = 7·481 U.S. gallons. |

| 1 imp. gallon | = 0·1605 cub. ft. | = 1·200 U.S. gallons. |

| 1 U.S. gallon | = 0·1337 cub. ft. | = 0·8333 imp. gallon. |

| 1 litre | = 0·2201 imp. gallon | = 0·2641 U.S. gallon. |

Density of Water.—Water at 53° F. and ordinary pressure contains 62·4 ℔ per cub. ft., or 10 ℔ per imperial gallon at 62° F. The litre contains one kilogram of water at 4° C. or 1000 kilograms per cubic metre. River and spring water is not sensibly denser than pure water. But average sea water weighs 64 ℔ per cub. ft. at 53° F. The weight of water per cubic unit will be denoted by G. Ice free from air weighs 57·28 ℔ per cub. ft. (Leduc).

§ 6. Compressibility of Liquids.—The most accurate experiments show that liquids are sensibly compressed by very great pressures, and that up to a pressure of 65 atmospheres, or about 1000 ℔ per sq. in., the compression is proportional to the pressure. The chief results of experiment are given in the following table. Let V1 be the volume of a liquid in cubic feet under a pressure p1 ℔ per sq. ft., and V2 its volume under a pressure p2. Then the cubical compression is (V2 − V1)/V1, and the ratio of the increase of pressure p2 − p1 to the cubical compression is sensibly constant. That is, k = (p2 − p1)V1/(V2 − V1) is constant. This constant is termed the elasticity of volume. With the notation of the differential calculus,

| k = dp / ( − | dV | ) = − V | dp | . |

| V | dV |

| Canton. | Oersted. | Colladon and Sturm. |

Regnault. | |

| Water | 45,990,000 | 45,900,000 | 42,660,000 | 44,000,000 |

| Sea water | 52,900,000 | ·· | ·· | ·· |

| Mercury | 705,300,000 | ·· | 626,100,000 | 604,500,000 |

| Oil | 44,090,000 | ·· | ·· | ·· |

| Alcohol | 32,060,000 | ·· | 23,100,000 | ·· |

According to the experiments of Grassi, the compressibility of water diminishes as the temperature increases, while that of ether, alcohol and chloroform is increased.

§ 7. Change of Volume and Density of Water with Change of Temperature.—Although the change of volume of water with change of temperature is so small that it may generally be neglected in ordinary hydraulic calculations, yet it should be noted that there is a change of volume which should be allowed for in very exact calculations. The values of ρ in the following short table, which gives data enough for hydraulic purposes, are taken from Professor Everett’s System of Units.

Density of Water at Different Temperatures.

| Temperature. | ρ Density of Water. | G Weight of 1 cub. ft. in ℔. | |

| Cent. | Fahr. | ||

| 0 | 32·0 | ·999884 | 62·417 |

| 1 | 33·8 | ·999941 | 62·420 |

| 2 | 35·6 | ·999982 | 62·423 |

| 3 | 37·4 | 1·000004 | 62·424 |

| 4 | 39·2 | 1·000013 | 62·425 |

| 5 | 41·0 | 1·000003 | 62·424 |

| 6 | 42·8 | ·999983 | 62·423 |

| 7 | 44·6 | ·999946 | 62·421 |

| 8 | 46·4 | ·999899 | 62·418 |

| 9 | 48·2 | ·999837 | 62·414 |

| 10 | 50·0 | ·999760 | 62·409 |

| 11 | 51·8 | ·999668 | 62·403 |

| 12 | 53·6 | ·999562 | 62·397 |

| 13 | 55·4 | ·999443 | 62·389 |

| 14 | 57·2 | ·999312 | 62·381 |

| 15 | 59·0 | ·999173 | 62·373 |

| 16 | 60·8 | ·999015 | 62·363 |

| 17 | 62·6 | ·998854 | 62·353 |

| 18 | 64·4 | ·998667 | 62·341 |

| 19 | 66·2 | ·998473 | 62·329 |

| 20 | 68·0 | ·998272 | 62·316 |

| 22 | 71·6 | ·997839 | 62·289 |

| 24 | 75·2 | ·997380 | 62·261 |

| 26 | 78·8 | ·996879 | 62·229 |

| 28 | 82·4 | ·996344 | 62·196 |

| 30 | 86 | ·995778 | 62·161 |

| 35 | 95 | ·99469 | 62·093 |

| 40 | 104 | ·99236 | 61·947 |

| 45 | 113 | ·99038 | 61·823 |

| 50 | 122 | ·98821 | 61·688 |

| 55 | 131 | ·98583 | 61·540 |

| 60 | 140 | ·98339 | 61·387 |

| 65 | 149 | ·98075 | 61·222 |

| 70 | 158 | ·97795 | 61·048 |

| 75 | 167 | ·97499 | 60·863 |

| 80 | 176 | ·97195 | 60·674 |

| 85 | 185 | ·96880 | 60·477 |

| 90 | 194 | ·96557 | 60·275 |

| 100 | 212 | ·95866 | 59·844 |

The weight per cubic foot has been calculated from the values of ρ, on the assumption that 1 cub. ft. of water at 39·2° Fahr. is 62·425 ℔. For ordinary calculations in hydraulics, the density of water (which will in future be designated by the symbol G) will be taken at 62·4 ℔ per cub. ft., which is its density at 53° Fahr. It may be noted also that ice at 32° Fahr. contains 57·3 ℔ per cub. ft. The values of ρ are the densities in grammes per cubic centimetre.

§ 8. Pressure Column. Free Surface Level.—Suppose a small vertical pipe introduced into a liquid at any point P (fig. 3). Then the liquid will rise in the pipe to a level OO, such that the pressure due to the column in the pipe exactly balances the pressure on its mouth. If the fluid is in motion the mouth of the pipe must be supposed accurately parallel to the direction of motion, or the impact of the liquid at the mouth of the pipe will have an influence on the height of the column. If this condition is complied with, the height h of the column is a measure of the pressure at the point P. Let ω be the area of section of the pipe, h the height of the pressure column, p the intensity of pressure at P; then

℔,

;

that is, h is the height due to the pressure at p. The level OO will be termed the free surface level corresponding to the pressure at P.

Relation of Pressure, Temperature, and Density of Gases

|

| Fig. 3. |

§ 9. Relation of Pressure, Volume, Temperature and Density in Compressible Fluids.—Certain problems on the flow of air and steam are so similar to those relating to the flow of water that they are conveniently treated together. It is necessary, therefore, to state as briefly as possible the properties of compressible fluids so far as knowledge of them is requisite in the solution of these problems. Air may be taken as a type of these fluids, and the numerical data here given will relate to air.

Relation of Pressure and Volume at Constant Temperature.—At constant temperature the product of the pressure p and volume V of a given quantity of air is a constant (Boyle’s law).

Let be mean atmospheric pressure (2116·8 ℔ per sq. ft.), the volume of 1 ℔ of air at 32° Fahr. under the pressure . Then

If is the weight per cubic foot of air in the same conditions,

For any other pressure , at which the volume of 1 ℔ is and the weight per cubic foot is , the temperature being 32° Fahr.,

Change of Pressure or Volume by Change of Temperature.—Let p0, V0, G0, as before be the pressure, the volume of a pound in cubic feet, and the weight of a cubic foot in pounds, at 32° Fahr. Let p, V, G be the same quantities at a temperature t (measured strictly by the air thermometer, the degrees of which differ a little from those of a mercurial thermometer). Then, by experiment,

where are the temperatures t and 32° reckoned from the absolute zero, which is −460·6° Fahr.;

If , then

Or quite generally for all gases, if is a constant varying inversely as the density of the gas at 32° F. For steam = 85·5.

II. KINEMATICS OF FLUIDS

§ 10. Moving fluids as commonly observed are conveniently classified thus:

(1) Streams are moving masses of indefinite length, completely or incompletely bounded laterally by solid boundaries. When the solid boundaries are complete, the flow is said to take place in a pipe. When the solid boundary is incomplete and leaves the upper surface of the fluid free, it is termed a stream bed or channel or canal.

(2) A stream bounded laterally by differently moving fluid of the same kind is termed a current.

(3) A jet is a stream bounded by fluid of a different kind.

(4) An eddy, vortex or whirlpool is a mass of fluid the particles of which are moving circularly or spirally.

(5) In a stream we may often regard the particles as flowing along definite paths in space. A chain of particles following each other along such a constant path may be termed a fluid filament or elementary stream.

§ 11. Steady and Unsteady, Uniform and Varying, Motion.—There are two quite distinct ways of treating hydrodynamical questions. We may either fix attention on a given mass of fluid and consider its changes of position and energy under the action of the stresses to which it is subjected, or we may have regard to a given fixed portion of space, and consider the volume and energy of the fluid entering and leaving that space.

|

| Fig. 4. |

If, in following a given path ab (fig. 4), a mass of water a has a constant velocity, the motion is said to be uniform. The kinetic energy of the mass a remains unchanged. If the velocity varies from point to point of the path, the motion is called varying motion. If at a given point a in space, the particles of water always arrive with the same velocity and in the same direction, during any given time, then the motion is termed steady motion. On the contrary, if at the point a the velocity or direction varies from moment to moment the motion is termed unsteady. A river which excavates its own bed is in unsteady motion so long as the slope and form of the bed is changing. It, however, tends always towards a condition in which the bed ceases to change, and it is then said to have reached a condition of permanent regime. No river probably is in absolutely permanent regime, except perhaps in rocky channels. In other cases the bed is scoured more or less during the rise of a flood, and silted again during the subsidence of the flood. But while many streams of a torrential character change the condition of their bed often and to a large extent, in others the changes are comparatively small and not easily observed.

As a stream approaches a condition of steady motion, its regime becomes permanent. Hence steady motion and permanent regime are sometimes used as meaning the same thing. The one, however, is a definite term applicable to the motion of the water, the other a less definite term applicable in strictness only to the condition of the stream bed.

§ 12. Theoretical Notions on the Motion of Water.—The actual motion of the particles of water is in most cases very complex. To simplify hydrodynamic problems, simpler modes of motion are assumed, and the results of theory so obtained are compared experimentally with the actual motions.

|

| Fig. 5. |

Motion in Plane Layers.—The simplest kind of motion in a stream is one in which the particles initially situated in any plane cross section of the stream continue to be found in plane cross sections during the subsequent motion. Thus, if the particles in a thin plane layer ab (fig. 5) are found again in a thin plane layer a′b′ after any interval of time, the motion is said to be motion in plane layers. In such motion the internal work in deforming the layer may usually be disregarded, and the resistance to the motion is confined to the circumference.

Laminar Motion.—In the case of streams having solid boundaries, it is observed that the central parts move faster than the lateral parts. To take account of these differences of velocity, the stream may be conceived to be divided into thin laminae, having cross sections somewhat similar to the solid boundary of the stream, and sliding on each other. The different laminae can then be treated as having differing velocities according to any law either observed or deduced from their mutual friction. A much closer approximation to the real motion of ordinary streams is thus obtained.

Stream Line Motion.—In the preceding hypothesis, all the particles in each lamina have the same velocity at any given cross section of the stream. If this assumption is abandoned, the cross section of the stream must be supposed divided into indefinitely small areas, each representing the section of a fluid filament. Then these filaments may have any law of variation of velocity assigned to them. If the motion is steady motion these fluid filaments (or as they are then termed stream lines) will have fixed positions in space.

|

| Fig. 6. |

Periodic Unsteady Motion.—In ordinary streams with rough boundaries, it is observed that at any given point the velocity varies from moment to moment in magnitude and direction, but that the average velocity for a sensible period (say for 5 or 10 minutes) varies very little either in magnitude or velocity. It has hence been conceived that the variations of direction and magnitude of the velocity are periodic, and that, if for each point of the stream the mean velocity and direction of motion were substituted for the actual more or less varying motions, the motion of the stream might be treated as steady stream line or steady laminar motion.

§ 13. Volume of Flow.—Let A (fig. 6) be any ideal plane surface, of area ω, in a stream, normal to the direction of motion, and let V be the velocity of the fluid. Then the volume flowing through the surface A in unit time is

Thus, if the motion is rectilinear, all the particles at any instant in the surface A will be found after one second in a similar surface A′, at a distance V, and as each particle is followed by a continuous thread of other particles, the volume of flow is the right prism AA′ having a base ω and length V.

If the direction of motion makes an angle θ with the normal to the surface, the volume of flow is represented by an oblique prism AA′ (fig. 7), and in that case

|

| Fig. 7. |

If the velocity varies at different points of the surface, let the surface be divided into very small portions, for each of which the velocity may be regarded as constant. If dω is the area and v, or v cos θ, the normal velocity for this element of the surface, the volume of flow is

as the case may be.

§ 14. Principle of Continuity.—If we consider any completely bounded fixed space in a moving liquid initially and finally filled continuously with liquid, the inflow must be equal to the outflow. Expressing the inflow with a positive and the outflow with a negative sign, and estimating the volume of flow Q for all the boundaries,

In general the space will remain filled with fluid if the pressure at every point remains positive. There will be a break of continuity, if at any point the pressure becomes negative, indicating that the stress at that point is tensile. In the case of ordinary water this statement requires modification. Water contains a variable amount of air in solution, often about one-twentieth of its volume. This air is disengaged and breaks the continuity of the liquid, if the pressure falls below a point corresponding to its tension. It is for this reason that pumps will not draw water to the full height due to atmospheric pressure.

Application of the Principle of Continuity to the case of a Stream.—If A1, A2 are the areas of two normal cross sections of a stream, and V1, V2 are the velocities of the stream at those sections, then from the principle of continuity,

that is, the normal velocities are inversely as the areas of the cross sections. This is true of the mean velocities, if at each section the velocity of the stream varies. In a river of varying slope the velocity varies with the slope. It is easy therefore to see that in parts of large cross section the slope is smaller than in parts of small cross section.

If we conceive a space in a liquid bounded by normal sections at A1, A2 and between A1, A2 by stream lines (fig. 8), then, as there is no flow across the stream lines,

as in a stream with rigid boundaries.

|

| Fig. 8. |

In the case of compressible fluids the variation of volume due to the difference of pressure at the two sections must be taken into account. If the motion is steady the weight of fluid between two cross sections of a stream must remain constant. Hence the weight flowing in must be the same as the weight flowing out. Let p1, p2 be the pressures, v1, v2 the velocities, G1, G2 the weight per cubic foot of fluid, at cross sections of a stream of areas A1, A2. The volumes of inflow and outflow are

and, if the weights of these are the same,

and hence, from (5a) § 9, if the temperature is constant,

|

| Fig. 9. |

| ||

| Fig. 10. | Fig. 11. | Fig. 12. |

|

| Fig. 13. |

§ 15. Stream Lines.—The characteristic of a perfect fluid, that is, a fluid free from viscosity, is that the pressure between any two parts into which it is divided by a plane must be normal to the plane. One consequence of this is that the particles can have no rotation impressed upon them, and the motion of such a fluid is irrotational. A stream line is the line, straight or curved, traced by a particle in a current of fluid in irrotational movement. In a steady current each stream line preserves its figure and position unchanged, and marks the track of a stream of particles forming a fluid filament or elementary stream. A current in steady irrotational movement may be conceived to be divided by insensibly thin partitions following the course of the stream lines into a number of elementary streams. If the positions of these partitions are so adjusted that the volumes of flow in all the elementary streams are equal, they represent to the mind the velocity as well as the direction of motion of the particles in different parts of the current, for the velocities are inversely proportional to the cross sections of the elementary streams. No actual fluid is devoid of viscosity, and the effect of viscosity is to render the motion of a fluid sinuous, or rotational or eddying under most ordinary conditions. At very low velocities in a tube of moderate size the motion of water may be nearly pure stream line motion. But at some velocity, smaller as the diameter of the tube is greater, the motion suddenly becomes tumultuous. The laws of simple stream line motion have hitherto been investigated theoretically, and from mathematical difficulties have only been determined for certain simple cases. Professor H. S. Hele Shaw has found means of exhibiting stream line motion in a number of very interesting cases experimentally. Generally in these experiments a thin sheet of fluid is caused to flow between two parallel plates of glass. In the earlier experiments streams of very small air bubbles introduced into the water current rendered visible the motions of the water. By the use of a lantern the image of a portion of the current can be shown on a screen or photographed. In later experiments streams of coloured liquid at regular distances were introduced into the sheet and these much more clearly marked out the forms of the stream lines. With a fluid sheet 0.02 in. thick, the stream lines were found to be stable at almost any required velocity. For certain simple cases Professor Hele Shaw has shown that the experimental stream lines of a viscous fluid are so far as can be measured identical with the calculated stream lines of a perfect fluid. Sir G. G. Stokes pointed out that in this case, either from the thinness of the stream between its glass walls, or the slowness of the motion, or the high viscosity of the liquid, or from a combination of all these, the flow is regular, and the effects of inertia disappear, the viscosity dominating everything. Glycerine gives the stream lines very satisfactorily.

Fig. 9 shows the stream lines of a sheet of fluid passing a fairly shipshape body such as a screwshaft strut. The arrow shows the direction of motion of the fluid. Fig. 10 shows the stream lines for a very thin glycerine sheet passing a non-shipshape body, the stream lines being practically perfect. Fig. 11 shows one of the earlier air-bubble experiments with a thicker sheet of water. In this case the stream lines break up behind the obstruction, forming an eddying wake. Fig. 12 shows the stream lines of a fluid passing a sudden contraction or sudden enlargement of a pipe. Lastly, fig. 13 shows the stream lines of a current passing an oblique plane. H. S. Hele Shaw, “Experiments on the Nature of the Surface Resistance in Pipes and on Ships,” Trans. Inst. Naval Arch. (1897). “Investigation of Stream Line Motion under certain Experimental Conditions,” Trans. Inst. Naval Arch. (1898); “Stream Line Motion of a Viscous Fluid,” Report of British Association (1898).

III. PHENOMENA OF THE DISCHARGE OF LIQUIDS FROM ORIFICES AS ASCERTAINABLE BY EXPERIMENTS

|

| Fig. 14. |

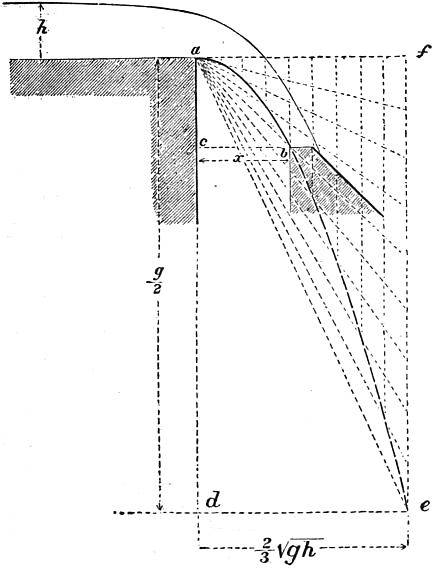

§ 16. When a liquid issues vertically from a small orifice, it forms a jet which rises nearly to the level of the free surface of the liquid in the vessel from which it flows. The difference of level hr (fig. 14) is so small that it may be at once suspected to be due either to air resistance on the surface of the jet or to the viscosity of the liquid or to friction against the sides of the orifice. Neglecting for the moment this small quantity, we may infer, from the elevation of the jet, that each molecule on leaving the orifice possessed the velocity required to lift it against gravity to the height h. From ordinary dynamics, the relation between the velocity and height of projection is given by the equation

As this velocity is nearly reached in the flow from well-formed orifices, it is sometimes called the theoretical velocity of discharge. This relation was first obtained by Torricelli.

If the orifice is of a suitable conoidal form, the water issues in filaments normal to the plane of the orifice. Let ω be the area of the orifice, then the discharge per second must be, from eq. (1),

This is sometimes quite improperly called the theoretical discharge for any kind of orifice. Except for a well-formed conoidal orifice the result is not approximate even, so that if it is supposed to be based on a theory the theory is a false one.

Use of the term Head in Hydraulics.—The term head is an old millwright’s term, and meant primarily the height through which a mass of water descended in actuating a hydraulic machine. Since the water in fig. 14 descends through a height h to the orifice, we may say there are h ft. of head above the orifice. Still more generally any mass of liquid h ft. above a horizontal plane may be said to have h ft. of elevation head relatively to that datum plane. Further, since the pressure p at the orifice which produces outflow is connected with h by the relation p/G = h, the quantity p/G may be termed the pressure head at the orifice. Lastly, the velocity v is connected with h by the relation v2/2g = h, so that v2/2g may be termed the head due to the velocity v.

§ 17. Coefficients of Velocity and Resistance.—As the actual velocity of discharge differs from √2gh by a small quantity, let the actual velocity

where cv is a coefficient to be determined by experiment, called the coefficient of velocity. This coefficient is found to be tolerably constant for different heads with well-formed simple orifices, and it very often has the value 0.97.

The difference between the velocity of discharge and the velocity due to the head may be reckoned in another way. The total height h causing outflow consists of two parts—one part he expended effectively in producing the velocity of outflow, another hr in overcoming the resistances due to viscosity and friction. Let

where cr is a coefficient determined by experiment, and called the coefficient of resistance of the orifice. It is tolerably constant for different heads with well-formed orifices. Then

The relation between cv and cr for any orifice is easily found:—

| cr = 1 / cv2 − 1. | (5a) |

Thus if cv = 0.97, then cr = 0.0628. That is, for such an orifice about 614% of the head is expended in overcoming frictional resistances to flow.

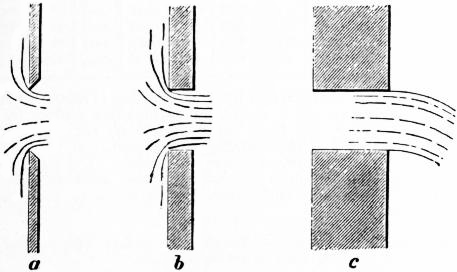

Coefficient of Contraction—Sharp-edged Orifices in Plane Surfaces.—When a jet issues from an aperture in a vessel, it may either spring clear from the inner edge of the orifice as at a or b (fig. 15), or it may adhere to the sides of the orifice as at c. The former condition will be found if the orifice is bevelled outwards as at a, so as to be sharp edged, and it will also occur generally for a prismatic aperture like b, provided the thickness of the plate in which the aperture is formed is less than the diameter of the jet. But if the thickness is greater the condition shown at c will occur.

When the discharge occurs as at a or b, the filaments converging towards the orifice continue to converge beyond it, so that the section of the jet where the filaments have become parallel is smaller than the section of the orifice. The inertia of the filaments opposes sudden change of direction of motion at the edge of the orifice, and the convergence continues for a distance of about half the diameter of the orifice beyond it. Let ω be the area of the orifice, and ccω the area of the jet at the point where convergence ceases; then cc is a coefficient to be determined experimentally for each kind of orifice, called the coefficient of contraction. When the orifice is a sharp-edged orifice in a plane surface, the value of cc is on the average 0.64, or the section of the jet is very nearly five-eighths of the area of the orifice.

|

| Fig. 16. |

Coefficient of Discharge.—In applying the general formula Q = ωv to a stream, it is assumed that the filaments have a common velocity v normal to the section ω. But if the jet contracts, it is at the contracted section of the jet that the direction of motion is normal to a transverse section of the jet. Hence the actual discharge when contraction occurs is

or simply, if c = cvcc,

where c is called the coefficient of discharge. Thus for a sharp-edged plane orifice c = 0.97 × 0.64 = 0.62.

§ 18. Experimental Determination of v, cc, and c.—The coefficient of contraction cc is directly determined by measuring the dimensions of the jet. For this purpose fixed screws of fine pitch (fig. 16) are convenient. These are set to touch the jet, and then the distance between them can be measured at leisure.

The coefficient of velocity is determined directly by measuring the parabolic path of a horizontal jet.

Let OX, OY (fig. 17) be horizontal and vertical axes, the origin being at the orifice. Let h be the head, and x, y the coordinates of a point A on the parabolic path of the jet. If va is the velocity at the orifice, and t the time in which a particle moves from O to A, then

Eliminating t,

Then

In the case of large orifices such as weirs, the velocity can be directly determined by using a Pitot tube (§ 144).

|

| Fig. 17. |

The coefficient of discharge, which for practical purposes is the most important of the three coefficients, is best determined by tank measurement of the flow from the given orifice in a suitable time. If Q is the discharge measured in the tank per second, then

Measurements of this kind though simple in principle are not free from some practical difficulties, and require much care. In fig. 18 is shown an arrangement of measuring tank. The orifice is fixed in the wall of the cistern A and discharges either into the waste channel BB, or into the measuring tank. There is a short trough on rollers C which when run under the jet directs the discharge into the tank, and when run back again allows the discharge to drop into the waste channel. D is a stilling screen to prevent agitation of the surface at the measuring point, E, and F is a discharge valve for emptying the measuring tank. The rise of level in the tank, the time of the flow and the head over the orifice at that time must be exactly observed.

For well made sharp-edged orifices, small relatively to the water surface in the supply reservoir, the coefficients under different conditions of head are pretty exactly known. Suppose the same quantity of water is made to flow in succession through such an orifice and through another orifice of which the coefficient is required, and when the rate of flow is constant the heads over each orifice are noted. Let h1, h2 be the heads, ω1, ω2 the areas of the orifices, c1, c2 the coefficients. Then since the flow through each orifice is the same

§ 19. Coefficients for Bellmouths and Bellmouthed Orifices.—If an orifice is furnished with a mouthpiece exactly of the form of the contracted vein, then the whole of the contraction occurs within the mouthpiece, and if the area of the orifice is measured at the smaller end, cc must be put = 1. It is often desirable to bellmouth the ends of pipes, to avoid the loss of head which occurs if this is not done; and such a bellmouth may also have the form of the contracted jet. Fig. 19 shows the proportions of such a bellmouth or bell-mouthed orifice, which approximates to the form of the contracted jet sufficiently for any practical purpose.

For such an orifice L. J. Weisbach found the following values of the coefficients with different heads.

| Head over orifice, in ft. = h | ·66 | 1·64 | 11·48 | 55·77 | 337·93 |

| Coefficient of velocity = cv | ·959 | ·967 | ·975 | ·994 | ·994 |

| Coefficient of resistance = cr | ·087 | ·069 | ·052 | ·012 | ·012 |

As there is no contraction after the jet issues from the orifice, cc = 1, c = cv; and therefore

§ 20. Coefficients for Sharp-edged or virtually Sharp-edged Orifices.—There are a very large number of measurements of discharge from sharp-edged orifices under different conditions of head. An account of these and a very careful tabulation of the average values of the coefficients will be found in the Hydraulics of the late Hamilton Smith (Wiley & Sons, New York, 1886). The following short table abstracted from a larger one will give a fair notion of how the coefficient varies according to the most trustworthy of the experiments.

Coefficient of Discharge for Vertical Circular Orifices, Sharp-edged,

with free Discharge into the Air. Q = cω √ (2gh).

| Head measured to Centre of Orifice. | Diameters of Orifice. | ||||||

| ·02 | ·04 | ·10 | ·20 | ·40 | ·60 | 1·0 | |

| Values of C. | |||||||

| 0·3 | .. | .. | ·621 | .. | .. | .. | .. |

| 0·4 | .. | ·637 | ·618 | .. | .. | .. | .. |

| 0·6 | ·655 | ·630 | ·613 | ·601 | ·596 | ·588 | .. |

| 0·8 | ·648 | ·626 | ·610 | ·601 | ·597 | ·594 | ·583 |

| 1·0 | ·644 | ·623 | ·608 | ·600 | ·598 | ·595 | ·591 |

| 2·0 | ·632 | ·614 | ·604 | ·599 | ·599 | ·597 | ·595 |

| 4·0 | ·623 | ·609 | ·602 | ·599 | ·598 | ·597 | ·596 |

| 8·0 | ·614 | ·605 | ·600 | ·598 | ·597 | ·596 | ·596 |

| 20·0 | ·601 | ·599 | ·596 | ·596 | ·596 | ·596 | ·594 |

At the same time it must be observed that differences of sharpness in the edge of the orifice and some other circumstances affect the results, so that the values found by different careful experimenters are not a little discrepant. When exact measurement of flow has to be made by a sharp-edged orifice it is desirable that the coefficient for the particular orifice should be directly determined.

The following results were obtained by Dr H. T. Bovey in the laboratory of McGill University.

Coefficient of Discharge for Sharp-edged Orifices.

| Head in ft. | Form of Orifice. | |||||||

| Circular. | Square. | Rectangular Ratio of Sides 4:1 | Rectangular Ratio of Sides 16:1 | Tri- angular. | ||||

| Sides Vertical. | Diagonal vertical. | Long Sides vertical. | Long Sides hori- zontal. | Long Sides vertical. | Long Sides hori- zontal. | |||

| 1 | ·620 | ·627 | ·628 | ·642 | ·643 | ·663 | ·664 | ·636 |

| 2 | ·613 | ·620 | ·628 | ·634 | ·636 | ·650 | ·651 | ·628 |

| 4 | ·608 | ·616 | ·618 | ·628 | ·629 | ·641 | ·642 | ·623 |

| 6 | ·607 | ·614 | ·616 | ·626 | ·627 | ·637 | ·637 | ·620 |

| 8 | ·606 | ·613 | ·614 | ·623 | ·625 | ·634 | ·635 | ·619 |

| 10 | ·605 | ·612 | ·613 | ·622 | ·624 | ·632 | ·633 | ·618 |

| 12 | ·604 | ·611 | ·612 | ·622 | ·623 | ·631 | ·631 | ·618 |

| 14 | ·604 | ·610 | ·612 | ·621 | ·622 | ·630 | ·630 | ·618 |

| 16 | ·603 | ·610 | ·611 | ·620 | ·622 | ·630 | ·630 | ·617 |

| 18 | ·603 | ·610 | ·611 | ·620 | ·621 | ·630 | ·629 | ·616 |

| 20 | ·603 | ·609 | ·611 | ·620 | ·621 | ·629 | ·628 | ·616 |

The orifice was 0·196 sq. in. area and the reductions were made with g = 32·176 the value for Montreal. The value of the coefficient appears to increase as (perimeter) / (area) increases. It decreases as the head increases. It decreases a little as the size of the orifice is greater.

Very careful experiments by J. G. Mair (Proc. Inst. Civ. Eng. lxxxiv.) on the discharge from circular orifices gave the results shown on top of next column.

The edges of the orifices were got up with scrapers to a sharp square edge. The coefficients generally fall as the head increases and as the diameter increases. Professor W. C. Unwin found that the results agree with the formula

where h is in feet and d in inches.

Coefficients of Discharge from Circular Orifices. Temperature 51° to 55°.

| Head in feet h. | Diameters of Orifices in Inches (d). | ||||||||

| 1 | 114 | 112 | 134 | 2 | 214 | 212 | 234 | 3 | |

| Coefficients (c). | |||||||||

| ·75 | ·616 | ·614 | ·616 | ·610 | ·616 | ·612 | ·607 | ·607 | ·609 |

| 1·0 | ·613 | ·612 | ·612 | ·611 | ·612 | ·611 | ·604 | ·608 | ·609 |

| 1·25 | ·613 | ·614 | ·610 | ·608 | ·612 | ·608 | ·605 | ·605 | ·606 |

| 1·50 | ·610 | ·612 | ·611 | ·606 | ·610 | ·607 | ·603 | ·607 | ·605 |

| 1·75 | ·612 | ·611 | ·611 | ·605 | ·611 | ·605 | ·604 | ·607 | ·605 |

| 2·00 | ·609 | ·613 | ·609 | ·606 | ·609 | ·606 | ·604 | ·604 | ·605 |

The following table, compiled by J. T. Fanning (Treatise on Water Supply Engineering), gives values for rectangular orifices in vertical plane surfaces, the head being measured, not immediately over the orifice, where the surface is depressed, but to the still-water surface at some distance from the orifice. The values were obtained by graphic interpolation, all the most reliable experiments being plotted and curves drawn so as to average the discrepancies.

Coefficients of Discharge for Rectangular Orifices, Sharp-edged, in Vertical Plane Surfaces.

| Head to Centre of Orifice. | Ratio of Height to Width. | |||||||

| 4 | 2 | 112 | 1 | 34 | 12 | 14 | 18 | |

| Feet. | 4 ft. high. 1 ft. wide. | 2 ft. high. 1 ft. wide. | 112 ft. high. 1 ft. wide. | 1 ft. high. 1 ft. wide. | 0·75 ft. high. 1 ft. wide. |

0·50 ft. high. 1 ft. wide. | 0·25 ft. high. 1 ft. wide. | 0·125 ft. high. 1 ft. wide. |

| 0·2 | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | ·6333 |

| ·3 | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | ·6293 | ·6334 |

| ·4 | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | ·6140 | ·6306 | ·6334 |

| ·5 | .. | .. | .. | .. | ·6050 | ·6150 | ·6313 | ·6333 |

| ·6 | .. | .. | .. | ·5984 | ·6063 | ·6156 | ·6317 | ·6332 |

| ·7 | .. | .. | .. | ·5994 | ·6074 | ·6162 | ·6319 | ·6328 |

| ·8 | .. | .. | ·6130 | ·6000 | ·6082 | ·6165 | ·6322 | ·6326 |

| ·9 | .. | .. | ·6134 | ·6006 | ·6086 | ·6168 | ·6323 | ·6324 |

| 1·0 | .. | .. | ·6135 | ·6010 | ·6090 | ·6172 | ·6320 | ·6320 |

| 1·25 | .. | ·6188 | ·6140 | ·6018 | ·6095 | ·6173 | ·6317 | ·6312 |

| 1·50 | .. | ·6187 | ·6144 | ·6026 | ·6100 | ·6172 | ·6313 | ·6303 |

| 1·75 | .. | ·6186 | ·6145 | ·6033 | ·6103 | ·6168 | ·6307 | ·6296 |

| 2 | .. | ·6183 | ·6144 | ·6036 | ·6104 | ·6166 | ·6302 | ·6291 |

| 2·25 | .. | ·6180 | ·6143 | ·6029 | ·6103 | ·6163 | ·6293 | ·6286 |

| 2·50 | ·6290 | ·6176 | ·6139 | ·6043 | ·6102 | ·6157 | ·6282 | ·6278 |

| 2·75 | ·6280 | ·6173 | ·6136 | ·6046 | ·6101 | ·6155 | ·6274 | ·6273 |

| 3 | ·6273 | ·6170 | ·6132 | ·6048 | ·6100 | ·6153 | ·6267 | ·6267 |

| 3·5 | ·6250 | ·6160 | ·6123 | ·6050 | ·6094 | ·6146 | ·6254 | ·6254 |

| 4 | ·6245 | ·6150 | ·6110 | ·6047 | ·6085 | ·6136 | ·6236 | ·6236 |

| 4·5 | ·6226 | ·6138 | ·6100 | ·6044 | ·6074 | ·6125 | ·6222 | ·6222 |

| 5 | ·6208 | ·6124 | ·6088 | ·6038 | ·6063 | ·6114 | ·6202 | ·6202 |

| 6 | ·6158 | ·6094 | ·6063 | ·6020 | ·6044 | ·6087 | ·6154 | ·6154 |

| 7 | ·6124 | ·6064 | ·6038 | ·6011 | ·6032 | ·6058 | ·6110 | ·6114 |

| 8 | ·6090 | ·6036 | ·6022 | ·6010 | ·6022 | ·6033 | ·6073 | ·6087 |

| 9 | ·6060 | ·6020 | ·6014 | ·6010 | ·6015 | ·6020 | ·6045 | ·6070 |

| 10 | ·6035 | ·6015 | ·6010 | ·6010 | ·6010 | ·6010 | ·6030 | ·6060 |

| 15 | ·6040 | ·6018 | ·6010 | ·6011 | ·6012 | ·6013 | ·6033 | ·6066 |

| 20 | ·6045 | ·6024 | ·6012 | ·6012 | ·6014 | ·6018 | ·6036 | ·6074 |

| 25 | ·6048 | ·6028 | ·6014 | ·6012 | ·6016 | ·6022 | ·6040 | ·6083 |

| 30 | ·6054 | ·6034 | ·6017 | ·6013 | ·6018 | ·6027 | ·6044 | ·6092 |

| 35 | ·6060 | ·6039 | ·6021 | ·6014 | ·6022 | ·6032 | ·6049 | ·6103 |

| 40 | ·6066 | ·6045 | ·6025 | ·6015 | ·6026 | ·6037 | ·6055 | ·6114 |

| 45 | ·6054 | ·6052 | ·6029 | ·6016 | ·6030 | ·6043 | ·6062 | ·6125 |

| 50 | ·6086 | ·6060 | ·6034 | ·6018 | ·6035 | ·6050 | ·6070 | ·6140 |

§ 21. Orifices with Edges of Sensible Thickness.—When the edges of the orifice are not bevelled outwards, but have a sensible thickness, the coefficient of discharge is somewhat altered. The following table gives values of the coefficient of discharge for the arrangements of the orifice shown in vertical section at P, Q, R (fig. 20). The plan of all the orifices is shown at S. The planks forming the orifice and sluice were each 2 in. thick, and the orifices were all 24 in. wide. The heads were measured immediately over the orifice. In this case,

§ 22. Partially Suppressed Contraction.—Since the contraction of the jet is due to the convergence towards the orifice of the issuing streams, it will be diminished if for any portion of the edge of the orifice the convergence is prevented. Thus, if an internal rim or border is applied to part of the edge of the orifice (fig. 21), the convergence for so much of the edge is suppressed. For such cases

G. Bidone found the following empirical formulae applicable:— Table of Coefficients of Discharge for Rectangular Vertical Orifices in Fig. 20.

| Head h above upper edge of Orifice in feet. | Height of Orifice, H − h, in feet. | |||||||||||

| 1.31 | 0.66 | 0.16 | 0.10 | |||||||||

| P | Q | R | P | Q | R | P | Q | R | P | Q | R | |

| 0.328 | 0.598 | 0.644 | 0.648 | 0.634 | 0.665 | 0.668 | 0.691 | 0.664 | 0.666 | 0.710 | 0.694 | 0.696 |

| .656 | 0.609 | 0.653 | 0.657 | 0.640 | 0.672 | 0.675 | 0.685 | 0.687 | 0.688 | 0.696 | 0.704 | 0.706 |

| .787 | 0.612 | 0.655 | 0.659 | 0.641 | 0.674 | 0.677 | 0.684 | 0.690 | 0.692 | 0.694 | 0.706 | 0.708 |

| .984 | 0.616 | 0.656 | 0.660 | 0.641 | 0.675 | 0.678 | 0.683 | 0.693 | 0.695 | 0.692 | 0.709 | 0.711 |

| 1.968 | 0.618 | 0.649 | 0.653 | 0.640 | 0.676 | 0.679 | 0.678 | 0.695 | 0.697 | 0.688 | 0.710 | 0.712 |

| 3.28 | 0.608 | 0.632 | 0.634 | 0.638 | 0.674 | 0.676 | 0.673 | 0.694 | 0.695 | 0.680 | 0.704 | 0.705 |

| 4.27 | 0.602 | 0.624 | 0.626 | 0.637 | 0.673 | 0.675 | 0.672 | 0.693 | 0.694 | 0.678 | 0.701 | 0.702 |

| 4.92 | 0.598 | 0.620 | 0.622 | 0.637 | 0.673 | 0.674 | 0.672 | 0.692 | 0.693 | 0.676 | 0.699 | 0.699 |

| 5.58 | 0.596 | 0.618 | 0.620 | 0.637 | 0.672 | 0.673 | 0.672 | 0.692 | 0.693 | 0.676 | 0.698 | 0.698 |

| 6.56 | 0.595 | 0.615 | 0.617 | 0.636 | 0.671 | 0.672 | 0.671 | 0.691 | 0.692 | 0.675 | 0.696 | 0.696 |

| 9.84 | 0.592 | 0.611 | 0.612 | 0.634 | 0.669 | 0.670 | 0.668 | 0.689 | 0.690 | 0.672 | 0.693 | 0.693 |

For rectangular orifices,

and for circular orifices,

when n is the length of the edge of the orifice over which the border extends, and p is the whole length of edge or perimeter of the orifice. The following are the values of cc, when the border extends over 14, 12, or 34 of the whole perimeter:—

| n/p | Cc Rectangular Orifices | Cc Circular Orifices |

| 0.25 | 0.643 | .640 |

| 0.50 | 0.667 | .660 |

| 0.75 | 0.691 | .680 |

|

|

| Fig. 20. | Fig. 21. |

For larger values of n/p the formulae are not applicable. C. R. Bornemann has shown, however, that these formulae for suppressed contraction are not reliable.

§ 23. Imperfect Contraction.—If the sides of the vessel approach near to the edge of the orifice, they interfere with the convergence of the streams to which the contraction is due, and the contraction is then modified. It is generally stated that the influence of the sides begins to be felt if their distance from the edge of the orifice is less than 2.7 times the corresponding width of the orifice. The coefficients of contraction for this case are imperfectly known.

|

| Fig. 22. |

§ 24. Orifices Furnished with Channels of Discharge.—These external borders to an orifice also modify the contraction.

The following coefficients of discharge were obtained with openings 8 in. wide, and small in proportion to the channel of approach (fig. 22, A, B, C).

| h2 − h1 in feet | h1 in feet. | |||||||||

| .0656 | .164 | .328 | .656 | 1.640 | 3.28 | 4.92 | 6.56 | 9.84 | ||

| A | 0.656 | .480 | .511 | .542 | .574 | .599 | .601 | .601 | .601 | .601 |

| B | .480 | .510 | .538 | .506 | .592 | .600 | .602 | .602 | .601 | |

| C | .527 | .553 | .574 | .592 | .607 | .610 | .610 | .609 | .608 | |

| A | 0.164 | .488 | .577 | .624 | .631 | .625 | .624 | .619 | .613 | .606 |

| B | .487 | .571 | .606 | .617 | .626 | .628 | .627 | .623 | .618 | |

| C | .585 | .614 | .633 | .645 | .652 | .651 | .650 | .650 | .649 | |

|

| Fig. 23. |

§ 25. Inversion of the Jet.—When a jet issues from a horizontal orifice, or is of small size compared with the head, it presents no marked peculiarity of form. But if the orifice is in a vertical surface, and if its dimensions are not small compared with the head, it undergoes a series of singular changes of form after leaving the orifice. These were first investigated by G. Bidone (1781–1839); subsequently H. G. Magnus (1802–1870) measured jets from different orifices; and later Lord Rayleigh (Proc. Roy. Soc. xxix. 71) investigated them anew.

Fig. 23 shows some forms, the upper figure giving the shape of the orifices, and the others sections of the jet. The jet first contracts as described above, in consequence of the convergence of the fluid streams within the vessel, retaining, however, a form similar to that of the orifice. Afterwards it expands into sheets in planes perpendicular to the sides of the orifice. Thus the jet from a triangular orifice expands into three sheets, in planes bisecting at right angles the three sides of the triangle. Generally a jet from an orifice, in the form of a regular polygon of n sides, forms n sheets in planes perpendicular to the sides of the polygon.

Bidone explains this by reference to the simpler case of meeting streams. If two equal streams having the same axis, but moving in opposite directions, meet, they spread out into a thin disk normal to the common axis of the streams. If the directions of two streams intersect obliquely they spread into a symmetrical sheet perpendicular to the plane of the streams.

|

| Fig. 24. |

Let a1, a2 (fig. 24) be two points in an orifice at depths h1, h2 from the free surface. The filaments issuing at a1, a2 will have the different velocities √ 2gh1 and √ 2gh2. Consequently they will tend to describe parabolic paths a1cb1 and a2cb2 of different horizontal range, and intersecting in the point c. But since two filaments cannot simultaneously flow through the same point, they must exercise mutual pressure, and will be deflected out of the paths they tend to describe. It is this mutual pressure which causes the expansion of the jet into sheets.

Lord Rayleigh pointed out that, when the orifices are small and the head is not great, the expansion of the sheets in directions perpendicular to the direction of flow reaches a limit. Sections taken at greater distance from the orifice show a contraction of the sheets until a compact form is reached similar to that at the first contraction. Beyond this point, if the jet retains its coherence, sheets are thrown out again, but in directions bisecting the angles between the previous sheets. Lord Rayleigh accepts an explanation of this contraction first suggested by H. Buff (1805–1878), namely, that it is due to surface tension.

§ 26. Influence of Temperature on Discharge of Orifices.—Professor W. C. Unwin found (Phil. Mag., October 1878, p. 281) that for sharp-edged orifices temperature has a very small influence on the discharge. For an orifice 1 cm. in diameter with heads of about 1 to 112 ft. the coefficients were:—

| Temperature F. | C. |

| 205° | .594 |

| 62° | .598 |

For a conoidal or bell-mouthed orifice 1 cm. diameter the effect of temperature was greater:—

| Temperature F. | C. |

| 190° | 0.987 |

| 130° | 0.974 |

| 60° | 0.942 |

an increase in velocity of discharge of 4% when the temperature increased 130°.

J. G. Mair repeated these experiments on a much larger scale (Proc. Inst. Civ. Eng. lxxxiv.). For a sharp-edged orifice 212 in. diameter, with a head of 1.75 ft., the coefficient was 0.604 at 57° and 0.607 at 179° F., a very small difference. With a conoidal orifice the coefficient was 0.961 at 55° and 0.981 at 170° F. The corresponding coefficients of resistance are 0.0828 and 0.0391, showing that the resistance decreases to about half at the higher temperature.

§ 27. Fire Hose Nozzles.—Experiments have been made by J. R. Freeman on the coefficient of discharge from smooth cone nozzles used for fire purposes. The coefficient was found to be 0.983 for 34-in. nozzle; 0.982 for 78 in.; 0.972 for 1 in.; 0.976 for 118 in.; and 0.971 for 114 in. The nozzles were fixed on a taper play-pipe, and the coefficient includes the resistance of this pipe (Amer. Soc. Civ. Eng. xxi., 1889). Other forms of nozzle were tried such as ring nozzles for which the coefficient was smaller.

IV. THEORY OF THE STEADY MOTION OF FLUIDS.

§ 28. The general equation of the steady motion of a fluid given under Hydrodynamics furnishes immediately three results as to the distribution of pressure in a stream which may here be assumed.

(a) If the motion is rectilinear and uniform, the variation of pressure is the same as in a fluid at rest. In a stream flowing in an open channel, for instance, when the effect of eddies produced by the roughness of the sides is neglected, the pressure at each point is simply the hydrostatic pressure due to the depth below the free surface.

(b) If the velocity of the fluid is very small, the distribution of pressure is approximately the same as in a fluid at rest.

(c) If the fluid molecules take precisely the accelerations which they would have if independent and submitted only to the external forces, the pressure is uniform. Thus in a jet falling freely in the air the pressure throughout any cross section is uniform and equal to the atmospheric pressure.

(d) In any bounded plane section traversed normally by streams which are rectilinear for a certain distance on either side of the section, the distribution of pressure is the same as in a fluid at rest.

Distribution of Energy in Incompressible Fluids.

§ 29. Application of the Principle of the Conservation of Energy to Cases of Stream Line Motion.—The external and internal work done on a mass is equal to the change of kinetic energy produced. In many hydraulic questions this principle is difficult to apply, because from the complicated nature of the motion produced it is difficult to estimate the total kinetic energy generated, and because in some cases the internal work done in overcoming frictional or viscous resistances cannot be ascertained; but in the case of stream line motion it furnishes a simple and important result known as Bernoulli’s theorem.

|

| Fig. 25. |

Let AB (fig. 25) be any one elementary stream, in a steadily moving fluid mass. Then, from the steadiness of the motion, AB is a fixed path in space through which a stream of fluid is constantly flowing. Let OO be the free surface and XX any horizontal datum line. Let ω be the area of a normal cross section, v the velocity, p the intensity of pressure, and z the elevation above XX, of the elementary stream AB at A, and ω1, p1, v1, z1 the same quantities at B. Suppose that in a short time t the mass of fluid initially occupying AB comes to A′B′. Then AA′, BB′ are equal to vt, v1t, and the volumes of fluid AA′, BB′ are the equal inflow and outflow = Qt = ωvt = ω1v1t, in the given time. If we suppose the filament AB surrounded by other filaments moving with not very different velocities, the frictional or viscous resistance on its surface will be small enough to be neglected, and if the fluid is incompressible no internal work is done in change of volume. Then the work done by external forces will be equal to the kinetic energy produced in the time considered.

The normal pressures on the surface of the mass (excluding the ends A, B) are at each point normal to the direction of motion, and do no work. Hence the only external forces to be reckoned are gravity and the pressures on the ends of the stream.

The work of gravity when AB falls to A′B′ is the same as that of transferring AA′ to BB′; that is, GQt (z − z1). The work of the pressures on the ends, reckoning that at B negative, because it is opposite to the direction of motion, is (pω × vt) − (p1ω1 × v1t) = Qt(p − p1). The change of kinetic energy in the time t is the difference of the kinetic energy originally possessed by AA′ and that finally acquired by BB′, for in the intermediate part A′B there is no change of kinetic energy, in consequence of the steadiness of the motion. But the mass of AA′ and BB′ is GQt/g, and the change of kinetic energy is therefore (GQt/g) (v12/2 − v2/2). Equating this to the work done on the mass AB,

Dividing by GQt and rearranging the terms,

or, as A and B are any two points,

Now v2/2g is the head due to the velocity v, p/G is the head equivalent to the pressure, and z is the elevation above the datum (see § 16). Hence the terms on the left are the total head due to velocity, pressure, and elevation at a given cross section of the filament, z is easily seen to be the work in foot-pounds which would be done by 1 ℔ of fluid falling to the datum line, and similarly p/G and v2/2g are the quantities of work which would be done by 1 ℔ of fluid due to the pressure p and velocity v. The expression on the left of the equation is, therefore, the total energy of the stream at the section considered, per ℔ of fluid, estimated with reference to the datum line XX. Hence we see that in stream line motion, under the restrictions named above, the total energy per ℔ of fluid is uniformly distributed along the stream line. If the free surface of the fluid OO is taken as the datum, and −h, −h1 are the depths of A and B measured down from the free surface, the equation takes the form

or generally

|

| Fig. 26. |

§ 30. Second Form of the Theorem of Bernoulli.—Suppose at the two sections A, B (fig. 26) of an elementary stream small vertical pipes are introduced, which may be termed pressure columns (§ 8), having their lower ends accurately parallel to the direction of flow. In such tubes the water will rise to heights corresponding to the pressures at A and B. Hence b = p/G, and b′ = p1/G. Consequently the tops of the pressure columns A′ and B′ will be at total heights b + c = p/G + z and b′ + c′ = p1/G + z1 above the datum line XX. The difference of level of the pressure column tops, or the fall of free surface level between A and B, is therefore

and this by equation (1), § 29 is (v12 − v2)/2g. That is, the fall of free, surface level between two sections is equal to the difference of the heights due to the velocities at the sections. The line A′B′ is sometimes called the line of hydraulic gradient, though this term is also used in cases where friction needs to be taken into account. It is the line the height of which above datum is the sum of the elevation and pressure head at that point, and it falls below a horizontal line A″B″ drawn at H ft. above XX by the quantities a = v2/2g and a′ = v12/2g, when friction is absent.

§ 31. Illustrations of the Theorem of Bernoulli. In a lecture to the mechanical section of the British Association in 1875, W. Froude gave some experimental illustrations of the principle of Bernoulli. He remarked that it was a common but erroneous impression that a fluid exercises in a contracting pipe A (fig. 27) an excess of pressure against the entire converging surface which it meets, and that, conversely, as it enters an enlargement B, a relief of pressure is experienced by the entire diverging surface of the pipe. Further it is commonly assumed that when passing through a contraction C, there is in the narrow neck an excess of pressure due to the squeezing together of the liquid at that point. These impressions are in no respect correct; the pressure is smaller as the section of the pipe is smaller and conversely.

|

| Fig. 27. |

Fig. 28 shows a pipe so formed that a contraction is followed by an enlargement, and fig. 29 one in which an enlargement is followed by a contraction. The vertical pressure columns show the decrease of pressure at the contraction and increase of pressure at the enlargement. The line abc in both figures shows the variation of free surface level, supposing the pipe frictionless. In actual pipes, however, work is expended in friction against the pipe; the total head diminishes in proceeding along the pipe, and the free surface level is a line such as ab1c1, falling below abc.

Froude further pointed out that, if a pipe contracts and enlarges again to the same size, the resultant pressure on the converging part exactly balances the resultant pressure on the diverging part so that there is no tendency to move the pipe bodily when water flows through it. Thus the conical part AB (fig. 30) presents the same projected surface as HI, and the pressures parallel to the axis of the pipe, normal to these projected surfaces, balance each other. Similarly the pressures on BC, CD balance those on GH, EG. In the same way, in any combination of enlargements and contractions, a balance of pressures, due to the flow of liquid parallel to the axis of the pipe, will be found, provided the sectional area and direction of the ends are the same.

|

| Fig. 28. |

|

| Fig. 29. |

The following experiment is interesting. Two cisterns provided with converging pipes were placed so that the jet from one was exactly opposite the entrance to the other. The cisterns being filled very nearly to the same level, the jet from the left-hand cistern A entered the right-hand cistern B (fig. 31), shooting across the free space between them without any waste, except that due to indirectness of aim and want of exact correspondence in the form of the orifices. In the actual experiment there was 18 in. of head in the right and 2012 in. of head in the left-hand cistern, so that about 212 in. were wasted in friction. It will be seen that in the open space between the orifices there was no pressure, except the atmospheric pressure acting uniformly throughout the system.

|

| Fig. 30. |

|

| Fig. 31. |

§ 32. Venturi Meter.—An ingenious application of the variation of pressure and velocity in a converging and diverging pipe has been made by Clemens Herschel in the construction of what he terms a Venturi Meter for measuring the flow in water mains. Suppose that, as in fig. 32, a contraction is made in a water main, the change of section being gradual to avoid the production of eddies. The ratio ρ of the cross sections at A and B, that is at inlet and throat, is in actual meters 5 to 1 to 20 to 1, and is very carefully determined by the maker of the meter. Then, if v and u are the velocities at A and B, u = ρv. Let pressure pipes be introduced at A, B and C, and let H1, H, H2 be the pressure heads at those points. Since the velocity at B is greater than at A the pressure will be less. Neglecting friction

Let h = H1 − H be termed the Venturi head, then

from which the velocity through the throat and the discharge of the main can be calculated if the areas at A and B are known and h observed. Thus if the diameters at A and B are 4 and 12 in., the areas are 12.57 and 113.1 sq. in., and ρ = 9,

If the observed Venturi head is 12 ft.,

and the discharge of the main is

|

| Fig. 32. |

|

| Fig. 33. |

Hence by a simple observation of pressure difference, the flow in the main at any moment can be determined. Notice that the pressure height at C will be the same as at A except for a small loss hf due to friction and eddying between A and B. To get the pressure at the throat very exactly Herschel surrounds it by an annular passage communicating with the throat by several small holes, sometimes formed in vulcanite to prevent corrosion. Though constructed to prevent eddying as much as possible there is some eddy loss. The main effect of this is to cause a loss of head between A and C which may vary from a fraction of a foot to perhaps 5 ft. at the highest velocities at which a meter can be used. The eddying also affects a little the Venturi head h. Consequently an experimental coefficient must be determined for each meter by tank measurement. The range of this coefficient is, however, surprisingly small. If to allow for friction, u = k √ {ρ2/(ρ2 − 1)} √(2gh), then Herschel found values of k from 0.97 to 1.0 for throat velocities varying from 8 to 28 ft. per sec. The meter is extremely convenient. At Staines reservoirs there are two meters of this type on mains 94 in. in diameter. Herschel contrived a recording arrangement which records the variation of flow from hour to hour and also the total flow in any given time. In Great Britain the meter is constructed by G. Kent, who has made improvements in the recording arrangement.

In the Deacon Waste Water Meter (fig. 33) a different principle is used. A disk D, partly counter-balanced by a weight, is suspended in the water flowing through the main in a conical chamber. The unbalanced weight of the disk is supported by the impact of the water. If the discharge of the main increases the disk rises, but as it rises its position in the chamber is such that in consequence of the larger area the velocity is less. It finds, therefore, a new position of equilibrium. A pencil P records on a drum moved by clockwork the position of the disk, and from this the variation of flow is inferred.

§ 33. Pressure, Velocity and Energy in Different Stream Lines.—The equation of Bernoulli gives the variation of pressure and velocity from point to point along a stream line, and shows that the total energy of the flow across any two sections is the same. Two other directions may be defined, one normal to the stream line and in the plane containing its radius of curvature at any point, the other normal to the stream line and the radius of curvature. For the problems most practically useful it will be sufficient to consider the stream lines as parallel to a vertical or horizontal plane. If the motion is in a vertical plane, the action of gravity must be taken into the reckoning; if the motion is in a horizontal plane, the terms expressing variation of elevation of the filament will disappear.[3]

|

| Fig. 34. |

Let AB, CD (fig. 34) be two consecutive stream lines, at present assumed to be in a vertical plane, and PQ a normal to these lines making an angle φ with the vertical. Let P, Q be two particles moving along these lines at a distance PQ = ds, and let z be the height of Q above the horizontal plane with reference to which the energy is measured, v its velocity, and p its pressure. Then, if H is the total energy at Q per unit of weight of fluid,

Differentiating, we get

for the increment of energy between Q and P. But

where the last term disappears if the motion is in a horizontal plane.

Now imagine a small cylinder of section ω described round PQ as an axis. This will be in equilibrium under the action of its centrifugal force, its weight and the pressure on its ends. But its volume is ωds and its weight Gω ds. Hence, taking the components of the forces parallel to PQ—

where ρ is the radius of curvature of the stream line at Q. Consequently, introducing these values in (1),

Currents

§ 34. Rectilinear Current.—Suppose the motion is in parallel straight stream lines (fig. 35) in a vertical plane. Then ρ is infinite, and from eq. (2), § 33,

Comparing this with (1) we see that

|

| Fig. 35. |

or the pressure varies hydrostatically as in a fluid at rest. For two stream lines in a horizontal plane, z is constant, and therefore p is constant.

Radiating Current.—Suppose water flowing radially between horizontal parallel planes, at a distance apart = δ. Conceive two cylindrical sections of the current at radii r1 and r2, where the velocities are v1 and v2, and the pressures p1 and p2. Since the flow across each cylindrical section of the current is the same,

The velocity would be infinite at radius 0, if the current could be conceived to extend to the axis. Now, if the motion is steady,

Hence the pressure increases from the interior outwards, in a way indicated by the pressure columns in fig. 36, the curve through the free surfaces of the pressure columns being, in a radial section, the quasi-hyperbola of the form xy2 = c3. This curve is asymptotic to a horizontal line, H ft. above the line from which the pressures are measured, and to the axis of the current.

|

| Fig. 36. |

Free Circular Vortex.—A free circular vortex is a revolving mass of water, in which the stream lines are concentric circles, and in which the total head for each stream line is the same. Hence, if by any slow radial motion portions of the water strayed from one stream line to another, they would take freely the velocities proper to their new positions under the action of the existing fluid pressures only.

For such a current, the motion being horizontal, we have for all the circular elementary streams

Consider two stream lines at radii r and r + dr (fig. 36). Then in (2), § 33, ρ = r and ds = dr,

precisely as in a radiating current; and hence the distribution of pressure is the same, and formulae 5 and 6 are applicable to this case.

Free Spiral Vortex.—As in a radiating and circular current the equations of motion are the same, they will also apply to a vortex in which the motion is compounded of these motions in any proportions, provided the radial component of the motion varies inversely as the radius as in a radial current, and the tangential component varies inversely as the radius as in a free vortex. Then the whole velocity at any point will be inversely proportional to the radius of the point, and the fluid will describe stream lines having a constant inclination to the radius drawn to the axis of the current. That is, the stream lines will be logarithmic spirals. When water is delivered from the circumference of a centrifugal pump or turbine into a chamber, it forms a free vortex of this kind. The water flows spirally outwards, its velocity diminishing and its pressure increasing according to the law stated above, and the head along each spiral stream line is constant.

§ 35. Forced Vortex.—If the law of motion in a rotating current is different from that in a free vortex, some force must be applied to cause the variation of velocity. The simplest case is that of a rotating current in which all the particles have equal angular velocity, as for instance when they are driven round by radiating paddles revolving uniformly. Then in equation (2), § 33, considering two circular stream lines of radii r and r + dr (fig. 37), we have ρ = r, ds = dr. If the angular velocity is α, then v = αr and dv = αdr. Hence

Comparing this with (1), § 33, and putting dz = 0, because the motion is horizontal,

Let p1, r1, v1 be the pressure, radius and velocity of one cylindrical section, p2, r2, v2 those of another; then

That is, the pressure increases from within outwards in a curve which in radial sections is a parabola, and surfaces of equal pressure are paraboloids of revolution (fig. 37).

|

| Fig. 37. |

Dissipation of Head in Shock

§ 36. Relation of Pressure and Velocity in a Stream in Steady Motion when the Changes of Section of the Stream are Abrupt.—When a stream changes section abruptly, rotating eddies are formed which dissipate energy. The energy absorbed in producing rotation is at once abstracted from that effective in causing the flow, and sooner or later it is wasted by frictional resistances due to the rapid relative motion of the eddying parts of the fluid. In such cases the work thus expended internally in the fluid is too important to be neglected, and the energy thus lost is commonly termed energy lost in shock. Suppose fig. 38 to represent a stream having such an abrupt change of section. Let AB, CD be normal sections at points where ordinary stream line motion has not been disturbed and where it has been re-established. Let ω, p, v be the area of section, pressure and velocity at AB, and ω1, p1, v1 corresponding quantities at CD. Then if no work were expended internally, and assuming the stream horizontal, we should have

head at the section CD will be diminished.

Suppose the mass ABCD comes in a short time t to A′B′C′D′. The resultant force parallel to the axis of the stream is

where p0 is put for the unknown pressure on the annular space between AB and EF. The impulse of that force is

|

| Fig. 38. |

The horizontal change of momentum in the same time is the difference of the momenta of CDC′D′ and ABA′B′, because the amount of momentum between A′B′ and CD remains unchanged if the motion is steady. The volume of ABA′B′ or CDC′D′, being the inflow and outflow in the time t, is Qt = ωvt = ω1v1t, and the momentum of these masses is (G/g) Qvt and (G/g) Qv1t. The change of momentum is therefore (G/g) Qt (v1 − v). Equating this to the impulse,

Assume that p0 = p, the pressure at AB extending unchanged through the portions of fluid in contact with AE, BF which lie out of the path of the stream. Then (since Q = ω1v1)

This differs from the expression (1), § 29, obtained for cases where no sensible internal work is done, by the last term on the right. That is, (v − v1)2/2g has to be added to the total head at CD, which is p1/G + v12/2g, to make it equal to the total head at AB, or (v − v1)2/2g is the head lost in shock at the abrupt change of section. But (v − v1) is the relative velocity of the two parts of the stream. Hence, when an abrupt change of section occurs, the head due to the relative velocity is lost in shock, or (v − v1)2/2g foot-pounds of energy is wasted for each pound of fluid. Experiment verifies this result, so that the assumption that p0 = p appears to be admissible.

If there is no shock,

If there is shock,

Hence the pressure head at CD in the second case is less than in the former by the quantity (v − v1)2/2g, or, putting ω1v1 = ωv, by the quantity

V. THEORY OF THE DISCHARGE FROM ORIFICES AND MOUTHPIECES

|

| Fig. 39. |

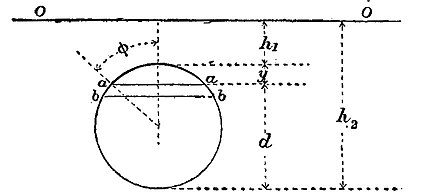

§ 37. Minimum Coefficient of Contraction. Re-entrant Mouthpiece of Borda.—In one special case the coefficient of contraction can be determined theoretically, and, as it is the case where the convergence of the streams approaching the orifice takes place through the greatest possible angle, the coefficient thus determined is the minimum coefficient.

Let fig. 39 represent a vessel with vertical sides, OO being the free water surface, at which the pressure is pa. Suppose the liquid issues by a horizontal mouthpiece, which is re-entrant and of the greatest length which permits the jet to spring clear from the inner end of the orifice, without adhering to its sides. With such an orifice the velocity near the points CD is negligible, and the pressure at those points may be taken equal to the hydrostatic pressure due to the depth from the free surface. Let Ω be the area of the mouthpiece AB, ω that of the contracted jet aa Suppose that in a short time t, the mass OOaa comes to the position O′O′ a′a′; the impulse of the horizontal external forces acting on the mass during that time is equal to the horizontal change of momentum.

The pressure on the side OC of the mass will be balanced by the pressure on the opposite side OE, and so for all other portions of the vertical surfaces of the mass, excepting the portion EF opposite the mouthpiece and the surface AaaB of the jet. On EF the pressure is simply the hydrostatic pressure due to the depth, that is, (pa + Gh). On the surface and section AaaB of the jet, the horizontal resultant of the pressure is equal to the atmospheric pressure pa acting on the vertical projection AB of the jet; that is, the resultant pressure is −paΩ. Hence the resultant horizontal force for the whole mass OOaa is (pa + Gh) Ω − paΩ = GhΩ. Its impulse in the time t is GhΩt. Since the motion is steady there is no change of momentum between O′O′ and aa. The change of horizontal momentum is, therefore, the difference of the horizontal momentum lost in the space OOO′O′ and gained in the space aaa′a′. In the former space there is no horizontal momentum.

The volume of the space aaa′a′ is ωvt; the mass of liquid in that space is (G/g)ωvt; its momentum is (G/g)ωv2t. Equating impulse to momentum gained,

But

a result confirmed by experiment with mouthpieces of this kind. A similar theoretical investigation is not possible for orifices in plane surfaces, because the velocity along the sides of the vessel in the neighbourhood of the orifice is not so small that it can be neglected. The resultant horizontal pressure is therefore greater than GhΩ, and the contraction is less. The experimental values of the coefficient of discharge for a re-entrant mouthpiece are 0.5149 (Borda), 0.5547 (Bidone), 0.5324 (Weisbach), values which differ little from the theoretical value, 0.5, given above.

|

|

| Fig. 40. | Fig. 41. |

§ 38. Velocity of Filaments issuing in a Jet.—A jet is composed of fluid filaments or elementary streams, which start into motion at some point in the interior of the vessel from which the fluid is discharged, and gradually acquire the velocity of the jet. Let Mm, fig. 40 be such a filament, the point M being taken where the velocity is insensibly small, and m at the most contracted section of the jet, where the filaments have become parallel and exercise uniform mutual pressure. Take the free surface AB for datum line, and let p1, v1, h1, be the pressure, velocity and depth below datum at M; p, v, h, the corresponding quantities at m. Then § 29, eq. (3a),

But at M, since the velocity is insensible, the pressure is the hydrostatic pressure due to the depth; that is v1 = 0, p1 = pa + Gh1. At m, p = pa, the atmospheric pressure round the jet. Hence, inserting these values,

| v2/2g = h; | (2) |

| or | v = √ (2gh) = 8.025V √ h | (2a) |

That is, neglecting the viscosity of the fluid, the velocity of filaments at the contracted section of the jet is simply the velocity due to the difference of level of the free surface in the reservoir and the orifice. If the orifice is small in dimensions compared with h, the filaments will all have nearly the same velocity, and if h is measured to the centre of the orifice, the equation above gives the mean velocity of the jet.