CHAPTER XII

THOMAS BEWICK AND HIS PUPILS

In the year 1775, the Society for the Encouragement of Arts offered a series of small money premiums for the best engravings on wood. These prizes were won by Thomas Hodgson, William Coleman, both then living in London, and Thomas Bewick, of Newcastle, who sent up for competition five engravings intended to illustrate a new edition of 'Gay's Fables.' It is of the last of these three—who received an award of seven guineas, which he immediately gave over to his mother—that we have now to write. He was born at Cherryburn, a farmhouse on the south bank of the Tyne, in the parish of Ovingham, about twelve miles from Newcastle, in August 1753. This we learn from an inscription now over the door of the 'byre,' or cowshed, which is still standing. His father was a farmer, who also rented a small coal-pit at Mickley, close by. After having received a fair education at local schools and at Ovingham parsonage, young Thomas, who had shown a great love of drawing, was in October 1767 apprenticed to Ralph Beilby, a general engraver, in St. Nicholas' Churchyard, Newcastle. Here the boy learned to cut diagrams in wood, engrave copper-plates for books, tradesmen's cards, etch ornament on sword-blades, and other work of the kind, much as Hogarth had done some fifty years before him; and, as luck would have it, his master received an order to engrave a series of wood-blocks to illustrate a 'Treatise on Mensuration' written by Mr. Charles Hutton, a schoolmaster in Newcastle—afterwards Dr. Hutton, a Fellow of the Royal Society. This work was issued in fifty sixpenny numbers, and published in a quarto volume in 1770. It was on this book that Thomas Bewick trained his 'prentice hand in the art in which he was afterwards to become so famous.

At the end of his apprenticeship in 1774, he worked with his old master for a short time at a guinea a week; then he went to live for a time at Cherryburn, and in 1776, with three guineas sewed in his waist-band, he walked to Edinburgh, Glasgow, and northwards to the Highlands, always staying at farm-houses on the road. He returned to Newcastle in a Leith sloop, and, after working till he had earned sufficient money, took a berth in a collier for London, where he arrived in October and soon found several Newcastle friends. But London life did not suit this child of the country-side. 'I would rather be herding sheep on Mickley bank top,' he writes to a friend, 'than remain in London, although for so doing I was to be made Premier of England.'

Soon after his return to Newcastle he joined his old master in partnership, and took his younger brother, John, as an apprentice, and for eight years the brothers made a weekly visit to Cherryburn, often fishing by the way. In the year 1785, their mother, father, and eldest sister all died, and in the following year Thomas Bewick married Isabella Elliot, of Ovingham, one of the companions of his childhood. He was at that time living in the 'fine, low, old-fashioned house'—with a long garden behind it, in which he cultivated roses—formerly occupied by Dr. Hutton; and going daily to work in the old house overlooking St. Nicholas' Churchyard.

We have previously said that the early wood-engravings were cut with a knife, held like a pen and drawn towards the craftsman, on 'planks' of the soft wood of the pear or apple-tree, or some similar tree. It is believed that Bewick was the first who used the wood of the box-tree, which is very hard, and who made his drawings on the butt-ends of the blocks, and cut his lines with the graver pushed from him. He brought into practice what is known as the 'white line' in wood-engraving; that is, he produced his effects more by means of many white lines wide apart to give an appearance of lightness, and by giving closer lines to produce a grey effect, as in our cut of 'The Yellowhammer.' He gave up the old method of obtaining 'colour,' as it is termed, by means of cross-hatching, and used a much simpler and more expeditious way of giving depth of shadow by leaving solid masses of the block, which of course printed black—and he constantly adopted the plan of lowering the wood in the background, and such parts of the block as were required to be printed lightly.

THE YELLOWHAMMER

(From 'The Land Birds')

The first book of real importance that was illustrated by Thomas Bewick was the 'Select Fables' published by Saint of Newcastle in 1784; this is now very rare; there is, however, a copy in the British Museum (press-mark 12305 g 16) which can at all times be consulted. Most of the designs are derived from 'Croxall's Fables,' and many of these were copied from the copper-plates by Francis Barlow in his edition of Æsop, published 'at his house, The Golden Eagle, in New Street, near Shoo Lane, 1665.' Though Bewick improved the drawings, there was little originality in them, but the engravings were far in advance of any other work of the kind done at that period. The success of this book induced him to carry out an idea he had long entertained of producing a series of illustrations for a 'General History of Quadrupeds,' on which he was engaged for six years, making the drawings and engraving them mostly in the evening. He tells us he had much difficulty in finding models, and was delighted when a travelling menagerie visited Newcastle and enabled him to depict many wild animals from nature. It was while he was employed on this work that he received a commission to make an engraving of a 'Chillingham Bull,' one of those famous wild cattle to which Sir Walter Scott refers in his ballad, 'Cadyow Castle':

- 'Mightiest of all the beasts of chase

- That roam in woody Caledon.'

He made the drawing on a block 7¾ inches by 5½ inches, and used his highest powers in rendering it as true to nature as he could; it is said that he always considered it to be his best work. After a few impressions had been taken off on paper and parchment, the block, which had been carelessly left by the printers in the direct rays of the sun, was split by the heat; and, though it was in after years clamped in gun-metal, no impressions could be taken which did not show a trace of the accident. Happily, one of the original impressions on parchment may be seen in the Townsend Collection in the South Kensington Museum. Meanwhile the 'Quadrupeds' were going on bravely: Ralph Beilby compiled the necessary text, which Bewick revised where he could, and in 1790 the book was published. It sold so well that a second edition was issued in 1791, and a third in 1792. Since then it has been frequently reprinted. [The first edition consisted of 1,500 copies in demy octavo at 8s., and 100 in royal octavo at 12s. The price of the eighth edition, with additional cuts, published in 1825, was one guinea.]

TAIL-PIECE

(From 'The Quadrupeds')

Besides the engravings of quadrupeds, the best that had appeared up to that time, the numerous tail-pieces which Bewick drew from nature charmed the public immensely. We give an example, one of them in which a small boy, said to be a young brother of the artist, is pulling a colt's tail, while the mother is rushing to his rescue. This little cut gives an admirable idea of their style. Many of them are humorous, many very pathetic, many grimly sarcastic, and all perfectly original.

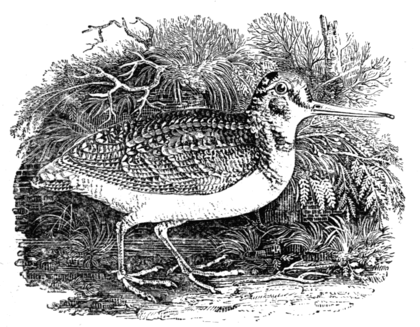

THE WOODCOCK

(From 'The Water Birds')

As soon as the success of the 'Quadrupeds' was assured, Bewick commenced without delay his still more celebrated book, the 'History of British Birds.' In making the drawings for this work he was much more at home, for he knew every feathered creature that flew within twenty miles of Ovingham, and it was all 'labour of love.' He worked with all his soul first at the 'Land Birds' and afterwards at the 'Water Birds,' and it is on these two books that Bewick's fame both as a draughtsman and an engraver principally rests. We give a copy of the 'Yellowhammer,' which the artist himself considered to be one of his best works, and the 'Woodcock,' in which all the excellences of his peculiar style may readily be traced.

The first volume, the 'Land Birds,' appeared in 1797, and was received with rapture by all lovers of nature. Again, the tail-pieces, pictures in miniature, were applauded to the skies, and the gratified author was beset on all sides with congratulations. Mr. Beilby wrote the descriptions as before, and performed his work very creditably.

A FARMYARD

(From 'The Land Birds')

The partnership between Ralph Beilby and Thomas Bewick was dissolved in 1797, and the descriptions to the second volume, 'The Water Birds,' which did not appear till 1804, were written by Bewick himself, and revised by the Rev. H. Cotes, Vicar of Bedlington. It is known that Bewick was assisted in the tail-pieces by his pupils, Robert Johnson as a draughtsman, and Luke Clennell as an engraver, but it is certain that every line was done under his immediate superintendence, and no doubt the originator of these excellent works was beginning to feel that he was no longer young.

[Of the first edition of the 'Land Birds' 1,000 were printed in demy octavo at 10s. 6d., 850 on thin and thick royal octavo, at 13s. and 15s., and twenty-four on imperial octavo at £1 1s. The first edition of the 'Water Birds' in 1804 consisted of the same number of copies as that of the 'Land Birds,' but the prices were increased respectively to 12s., 15s., 18s., and £1 4s.]

The only book of importance on which Bewick was engaged after 1804 was an edition of 'Æsop's Fables,' which was published in 1818. Mr. Chatto says: 'Whatever may be the merits or defects of the cuts in the Fables, Bewick certainly had little to do with them—for by far the greater number were designed by Robert Johnson and engraved by W. W. Temple and William Harvey, while yet in their apprenticeship.' Bewick amused himself by re-writing the Fables, to which he contributed a few of his own, but he was in no sense a literary man, and several of his greatest admirers openly expressed their disappointment at the book; even his supreme advocate, Dr. Dibdin, said: 'I will fearlessly and honestly aver that his "Æsop" disappointed me.'

In 1826 Bewick lost his wife, who left to his care one son and three daughters. In the summer of 1828 he visited London alone; he was not in good health, took but little interest in what was going on, and soon longed to return home. There he was busy as ever on a large cut of an old horse 'Waiting for Death' (which Mr. Linton has faithfully copied). Early in November he took the block to the printers to be proved, and after a few days' illness, he died on November 8, 1828. He was buried in Ovingham churchyard, where a tablet is erected to his memory. But his books are his true monument, and they will live for ever.