CHAPTER VII

PROGRESS OF THE PLOT

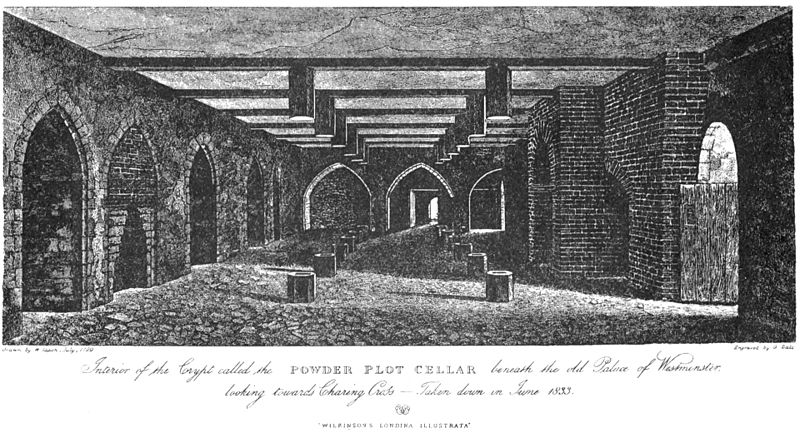

THE vague idea of blowing up the Parliament House seems first to have occurred to Robert Catesby 'about Lent,' 1604. Roughly speaking, we may date the genesis of the actual conspiracy from about April in that year. The first formal meeting of the first three plotters (Catesby, Thomas Winter, and John Wright) was held at a house in Lambeth, probably at the end of March, 1604. Later on, after the admission of Percy into the conspiracy, an empty house, with a small garden, adjoining the Palace of Westminster, was hired.[1] This house rented in Thomas Percy's[2] name, was leased by one Ferris as tenant to Mr. Whyneard, keeper of the King's wardrobe. From a cellar in this house the conspirators began digging a mine through the wall into the contiguous vault beneath the Parliament House; but the work proved much harder than anticipated, as the wall was immensely thick—nearly nine feet—and all the rubbish displaced in the course of their toil had to be buried in the garden. Whilst still at work (December, 1604), they suddenly learned that the meeting of Parliament had been prorogued from February 7 (1605), till October 3. The conspirators, therefore, took a holiday until after Christmas before resuming their labours. On returning to their terrible task, at the end of January, they found it no easier, till one day they were startled by hearing a peculiar rumbling noise over their heads. Guy Faukes, who acted as a kind of outside porter and sentinel to the confederates engaged within, on inquiry found that the tenant of the cellar almost above them was removing, and his coals (in which he traded) were being taken away. Percy immediately hired this cellar on the pretext that he wished to use it to keep fuel and coal. He had not taken it more than a month before he and his confederates, having abandoned their now unnecessary task of digging through the lower wall, had succeeded in depositing within it barrels of gunpowder [3] brought by water from their house at Lambeth. In May (1605) they separated, to meet once more in London at the end of September.

On their reunion, they received important news, the meeting of Parliament had again been postponed—until November 5. This further prorogation considerably alarmed the conspirators, many of whom were very superstitious, and looked upon this delay as ominous of ill-fortune. At first, they thought their project had been discovered; but inquiries set on foot by Thomas Winter, Percy, and Faukes, failed to elicit that the Government had obtained any inkling of their scheme. This last prorogation, brief though it was, proved the death-warrant of all the conspirators. Catesby, in need of more money for the furtherance of the rebellion in the Midlands, which was to take place after the explosion had occurred at Westminster, required more recruits. He, accordingly, selected two, Sir Everard Digby and Francis Tresham. Both responded to his appeals for money, and to Digby, who was never prominently engaged in the Westminster part of the plot, was deputed the office of heading the rebellion in the Midlands.

In selecting Tresham as the last, but not the least, of his recruits, Catesby made his first—and fatal—mistake since he had started the conspiracy. He was well aware of Tresham's unreliable character, but the wealth that this new recruit could pour into the coffers of the conspiracy was too strong an inducement to be ignored. Moreover, Tresham's friendship with several of the Roman Catholic Peers, two of whom had married his sisters, was a circumstance that Catesby thought would prove useful to the furtherance of the plotter's plans. As a matter of fact, these very reasons which led Catesby to act against his better judgment, in selecting Francis Tresham, were actually to prove the very reasons which induced Tresham to turn traitor. Tresham had too recently become a rich man to view with equanimity the prospect of spending much of his wealth on promoting so wild a scheme; whilst his relationship to Lords Mounteagle and Stourton only made him dangerously anxious to give them a hint of what was going on, in order to save their lives. Catesby soon discovered that he had committed a grievous error in choosing Francis Tresham, and is said to have bitterly repented of having let him into the secret of the plot. He caused a watch to be set upon Tresham's movements.

Meanwhile, by the middle of October, the plans of the conspirators were definitely decided upon. These plans comprised the following schemes:—

1. To blow up the King, Queen, Prince of Wales, Lords, and Commons, at Westminster, by means of the mine to be fired by Guy Faukes.

2. An attempt to capture the Duke of York (Prince Charles).[4]

3. An insurrection in the Midlands; the meeting-place to be Dunsmoor Heath, whence Digby and his friends were to proceed to Lord Harrington's house, Combe Abbey, near Coventry, there

4. To seize the person of the little Princess Elizabeth (afterwards Queen of Bohemia), who, in the event of Prince Charles remaining untaken, was to be proclaimed Queen.

5. To seize the person of the baby Princess Mary.

Such had been the preparations made when Catesby, Faukes, and Thomas Winter met on, or about October 18, at a house called White Webbs, on the confines of Enfield Chase; a building, the secret chambers of which had more than once afforded harbours of refuge to priests, and especially Jesuits.[5] Here they received a visit from Tresham, who appeared to be very much dejected. He came to them, he said, in a state of terrible anxiety. His conscience pricked him. He could obtain no peace of mind until they had satisfied him on one important point, namely, might he be allowed to warn his two noble relatives of their danger?

Although greatly alarmed at Tresham's behaviour, Catesby proceeded to discuss the matter calmly with him; but as to what was the exact substance of the evasive reply he gave Tresham we are still in the dark. But that Tresham had already approached Lord Mounteagle on the subject of the conspiracy before going to White Webbs seems clear. That Catesby suspected this, but refrained from letting Tresham know that he suspected this, seems equally plain. Francis Tresham's object in going to White Webbs was, without doubt, if possible to upset the plot altogether. He advised Catesby to postpone the explosion to a later date, and to seek safety by flying, pro tem., with the majority of the conspirators to Flanders, Faukes alone to remain in London. As to the balance of the money which he had promised to provide, he asserted that it could not be raised by the fifth of the forthcoming month.

It is surprising, considering how thoroughly alarmed were Catesby and his friends at White Webbs at Tresham's fears and excuses, that they should have let Tresham go back unharmed to London. They seem, at first, to have meditated capturing him, and keeping him under lock and key till after the fifth. It would have been better had they elected to do so; but they probably were afraid that his visit to White Webbs was already known to Mounteagle, or even to Cecil himself, and that his non-return to London, in consequence might give the alarm.

On leaving White Webbs, the evil results of Tresham's visit were quickly forthcoming; for on Saturday, October 26, occurred an event which will ever remain memorable in our history, since it sealed the fate of all the conspirators engaged in the Gunpowder Plot. This event was the receipt of the famous anonymous letter sent to Lord Mounteagle.

But, before dealing with the delivery of this mysterious letter, it should be stated that Mounteagle was by no means the only one of the Roman Catholic peers whom one or more of the conspirators had hoped to save, by giving them a hint to prevent their attending the opening of Parliament. The greater number of the conspirators were naturally unwilling to sacrifice members of their own communion, and were most desirous of giving them warning, without, at the same time, divulging the existence of the conspiracy. Among the names which have come down to us of the peers, Roman Catholic or Protestant, whom certain of the plotters implored Robert Catesby to save, we find mentioned the Earl of Northumberland, Lord Arundel, Lord Mordaunt, Viscount Montague, Lord Vaux, and Lord Stourton. At first, Catesby held out against giving any one of these a hint; declaring that the necessity of secrecy demanded that even the innocent should perish with the guilty, rather than the success of the plot should be endangered by disclosing its existence to outsiders. Of Lord Mordaunt he declared that he 'would not for a chamber full of diamonds acquaint him with their secret, for he knew he could not keep it.' At last, under pressure, he relented, and promised that those Roman Catholic peers who were likely to be present should be, by some means or other, hindered from putting in an appearance. 'I do not' records Sir Everard Digby,[6] 'think there were three worth saving that should have been lost; you may guess that I had some friends that were in danger, which I prevented.' But, by the time Catesby had consented to save some of those for whom intercession had been made by Keyes, Faukes, Digby, and Tresham, the latter had rendered all their good intentions void, by the delivery of the letter to Lord Mounteagle, who passed it on to Cecil, by whom, after examination before the Privy Council, it was handed to King James.

- ↑ The decision to hire this abode was taken at a meeting of five of the conspirators held in a lonely house near Clement's Inn.

- ↑ 'Thomas Percy hired a house at Westminster' (Confession of Guy Faukes).

- ↑ Accounts differ as to the number of the barrels, and consequently as to the total weight. The barrels were not, however, all of the same size. We may, I think, put the total at not less than two tons' weight of powder.

- ↑ Afterwards Charles I. The conspirators presumed that his elder brother Henry, Prince of Wales, would perish in the explosion.

- ↑ Garnet had been there very recently.

- ↑ Writing, when in the Tower, to his wife. This callous admission—that there were, perhaps, 'three' Catholics who would have been killed—should be quoted in evidence against the fulsome panegyrics which have been lavished by certain writers on the character of Sir Everard Digby.