Archaeological Journal/Volume 4/Some Account of the Parish Church of Bakewell in Derbyshire

SOME ACCOUNT OF THE PARISH CHURCH OF BAKEWELL IN DERBYSHIRE,

AND OF THE EARLY GRAVE-STONES AND OTHER REMAINS DISCOVERED DURING THE RECENT REPAIRS.

The town of Bakewell[1] is situated in one of the most beautiful vales in Derbyshire, at the entrance into the Peak district, on the high road, and nearly midway between Matlock and Buxton. It is so well known, on account of the many objects of interest with which its immediate neighbourhood abounds, that any further description is unnecessary. It will only be added, that it has been a place of some importance from a very remote period; a stronghold having been erected in its immediate vicinity, as early as in 924, by Edward the Elder, son of Alfred the Great, in his struggle with the Danes for possession of this part of the kingdom of Mercia; the earth-works of which, it is said, may be yet traced on Castle hill, within a short distance of the town.

In the year 1841, it was found necessary to commence some extensive repairs in the parish church; in the course of this work a large number of incised grave-stones, or coffin-lids as they are sometimes called, with crosses of various devices cut upon them, of very early date, were discovered, together with fragments of stones, carved with the interlacing bands, or knots, which are usually considered characteristic of those ancient monuments, known by the name of Runic crosses. As these remains are remarkable on several considerations, and no detailed description of them, so far as I am aware, has yet appeared, the following account may be acceptable to those who feel an interest in tracing out the history of the early sepulchral monuments in this country.

It will be desirable first to state some particulars respecting the church, in which these remains were found; both because it contains several architectural features in themselves well worthy of notice, and presents some curious illustrations of the way in which additions in different styles are often found to be engrafted upon the works of preceding periods, and because we shall thereby be enabled to ascertain the probable date of some portion of these ancient grave-stones. The present edifice is a cruciform structure of considerable size, being about 150 feet in length, and 105 feet across the transepts, of lofty elevation, erected at different periods, but externally presenting a general uniformity of outline, from the flat roofs and battlements, added throughout nearly the entire line of building, probably early in the fifteenth century. An octagonal tower resting on a square base, with the angles boldly cut off, rises from the centre, surmounted by a lofty spire. In the church-yard is one of those remarkable so called Runic crosses, which whatever may be their real origin, are confessedly of high antiquity. Very few particulars respecting the history of the foundation of this church, or of the circumstances under which the several additions were made to the original fabric, have been preserved. One might be disposed to conjecture, that a church, or chapel of some kind, may have been erected on or near this spot from a very remote period, in connection with the ancient cross before mentioned; especially since, as will afterwards be shewn, fragments of at least three other crosses of a similar kind were taken out of the foundations of a part of the present church. But no record has been preserved of any thing respecting its ecclesiastical history before the Norman conquest. In the Doomsday Survey it is stated there were two priests for the church of Bake ell. It was afterwards made a collegiate church, but to whom it was indebted for its endowment is by no means clear. The local tradition, which ascribes to John earl of Morton, afterwards King John, both the building of the present nave, with the exception of the west end, which he is said to have left standing, and the grant of the endowment in 1170, or 1180, or indeed at any later period, does not appear to rest upon any good authority. For John did not come into possession of this domain till 1189. It had formerly been granted by William the Conqueror to his natural son, William Peverel; and having been forfeited to the king by one of his descendants in 1154, it seems to have remained in possession of the crown, till it was given by Richard, on his accession to the throne in 1189, to his brother John. The church was certainly endowed before 1192; for in that year the earl gave it, with all its "prebends and other appurtenances," to the present cathedral of Lichfield, (see Dugdale, Monast. Lichfield,) and he is hardly likely to have so soon transferred this endowment if it had been made by himself. It seems more probable that the church was built and endowed by one of the Peverels, before their lands were forfeited. And as William Peverel, the son, who died in 1113, gave two parts of the tithes of the extensive parish of Bakewell to the priory which he founded at Lenton, in Notts., and was a great benefactor to other religious houses in this and the adjoining counties, it seems a reasonable conjecture that he may have given the other moiety of the tithes for the endowment of these prebends, and may also at the same time have erected the church, of which the present nave and west end formed a part: the date would thus be in the commencement of the twelfth century, and the style of what remains very well accords with that period.

The only other record of importance in the history of this church which has been preserved, is the founding of a chantry in 1365, by Sir Godfrey Foljambe, and Avena his wife, whose monument, two upright half length figures under a canopy, is inserted into one of the piers on the south side of the nave.

The present nave then was probably erected c. 1110. In the interior, it is separated from the side aisles by arches resting on piers of solid masonry, instead of pillars. These are mostly about 6 feet 6 inches wide, 3 feet thick, and 12 feet high to the impost, and the openings between them vary from 10 feet 6 inches, to 12 feet.

| |

The arches are semicircular, of rude construction, square- edged, not recessed, and without mouldings. The imposts have been plain projecting blocks with a chamfered edge, resting on corbels, resembling a common Norman corbel-table; one only is left, the others have been cut away, or replaced by a plain chamfered impost without corbels. Some of the original clerestory windows still remain, inserted over the centre of the piers, and now opening into the side aisles, the walls and roof of which were raised about the middle or end of the thirteenth century. These windows are narrow lights externally, resting upon a weather-table, still perfect, with a very wide splay towards the nave, of rude workmanship, and without any relief of mouldings, or string-course. Above is another range of clerestory windows, square-headed, in the early Perpendicular style, added probably early in the fifteenth century. The west walls of the side aisles are recessed with arches, but whether intended for doorways, an unusual arrangement in Norman churches of this size, or, as is more probable, for strength, as if to support western towers, the wall being very thick, cannot now be ascertained; the outer surface of the wall having been since cased with plain masonry, obliterating nearly all traces of its original character. In the centre of the west front is a doorway ornamented with beak-heads, and other heads of un- usual design with scrolls issuing from the mouths. Above are the remains of an arcade of intersecting arches with zig-zag work, in part cut away to admit the insertion of a sharp- pointed window, with early Perpendicular tracery; and a flat roof and battlements were put up when the clerestory was added to the nave. The north aisle has been widened, but the line of the original wall may easily be traced by the Norman base-moulding on the outside of the west end.

The central tower and the transepts were originally Norman, and, so far as could be ascertained, of the same date as the nave. The tower-piers, which were taken down in 1841, had been obviously cut away in parts, and altered by the addition of side shafts, to carry the ribs of the pointed arches set upon them, about the middle of the thirteenth century. There is also good reason to believe, that the walls of the north transept were either in part the original Norman walls, projecting, as was usual in the smaller churches, but little beyond the line of the walls of the side aisles, with additions of Early English work; or that at all events they stood upon the site of the old foundation. And as it will generally be found that in the older churches, the transepts correspond very nearly with each other in their dimensions, it may be fairly presumed that a short Norman transept had originally been erected on the south similar to that on the north. The chancel also had evidently been of Norman construction, for part of a corbel-table still remains in the upper end of the north wall of the chancel, next the tower-pier, shewing the continuation of the older masonry. This chancel would probably be short, and have the usual apsidal termination, as may be represented by the. imaginary dotted line; and thus the ground-plan of this church would correspond very nearly with that of Melbourne in the same county.

The upper part of this tower and the south transept were taken down and rebuilt about the middle of the thirteenth century; the transept being considerably lengthened, and, from its greater importance, distinguished by the name of the Newark, (new work,) a title which it still retains. It was a fine example of the peculiar beauties of the Early English style, with its lofty sharp-pointed arches, and all the mouldings bold and well expressed. On the west side were three long, narrow lights. The south front must have presented a striking effect before the gable was taken down, and the straight parapet added. Its central doorway was enriched with tooth moulding, and divided by a clustered shaft with a circle in the head; above was a lofty window of four lights, with circles in the intersections, bearing a close resemblance to geometrical tracery; indeed, the mouldings of the mullions, as shewn by a drawing made before this front was taken down, are so like the Decorated, and the use of a shaft in the outer splay so much larger than its nook, is so un- usual, that one can hardly help suspecting the window has been altered from its original design at a somewhat later period. Traces of featherings in the circles were discovered, and have been restored in the new work. The present side shafts, which have been faithfully copied from the old, have a singularly unpleasing effect, from the cause above stated, being like three-quarter shafts set against a flat wall without any relief.The east wall of this transept had been originally pierced with Early English arches, leading into side chapels; for there is no doubt the Vernon chapel was constructed on what were the original walls up to the window sill, as the same base-mouldings and string-course are continued along both the transept and chapel. The north transept has been altered or rebuilt either at the same time, or, at all events, within a very few years after the tower and south transept. And the windows are a late insertion.

The description of the remaining parts of the church may be briefly stated. The north aisle had been widened, and the wall of the south aisle rebuilt on the Norman foundation, about the same time as the transepts. The doorways, and small windows near the west end have the usual Early English character, the other windows being probably later insertions. The chancel has been rebuilt very early in the Decorated period. It is lighted by three windows on each side, and by two at the east end, which are separated externally by a buttress carried up nearly as high as the top of the arches. Each window is divided by a mullion with plain open head, and the inner arch is stilted in a remarkable manner, producing by no means a pleasing effect.

The Vernon chapel, as was before stated, was constructed late in the Decorated period, c. 1360, upon the walls of the former chapel. The Early English half pillars at each extremity of the arches had been retained, and were very beautiful examples, well worthy of imitation, the hollows of the mouldings, up to a certain height, being filled with bold roses; capitals in a different style were afterwards added to suit the Decorated arches.

| |

The central pillars, with their slender clustered shafts, are of singularly elegant design; the tracery of the windows partakes of the flamboyant character. And the section of the window will shew how ingeniously the Early English mouldings had been adapted to the new design. The upper part of the buttresses was also altered to correspond with the new work.

| |

This chapel, which has long been used as a burial-place for many noble members of the Vernon and Manners families, the successive owners of Haddon hall, will bear comparison with any structure of its kind in England; and it has been rebuilt in a manner which reflects great credit upon the architect. The most remarkable among these monuments is a well-executed effigy in alabaster of a knight in plate armour, said to represent Sir Thomas Wendesley, knight, who died in 1403. Upon his helmet is inscribed IHC NAZAREN. Lastly, an octagonal tower and spire were added to the Early English base, about the end of the fourteenth or the beginning of the fifteenth century, for the details retained much of the Decorated character; and about the same time the clerestory seems to have been added to the nave, and the flat roofs and battlements substituted for the high-pitched roofs of the transepts and chancel.

Some years ago the Norman tower-piers, which it was afterwards discovered were a mere mass of rubble in the interior without sufficient bond-stones, began to give way under the weight of these successive additions. The side walls could not sustain the pressure thus brought upon them, and after every expedient to stay the ruin had been tried in vain, by first taking off the spire in 1825, then the octagon tower in 1830, and by cramping together the walls, it was found necessary in 1841 to take down the whole of the remainder of the tower, and both the transepts with the Vernon chapel[2].

It was in the course of this work that the remains were discovered, of which we may now proceed to give some account. They consist, in part, of several fragments of stone carved with interlacing bands, and other devices, so closely resembling those on the cross in the church-yard, before mentioned, and more especially those on the cross at Eyam, a few miles distant, that there can be no doubt they may all be referred to the same period, whatever that may be determined to be. A more detailed description of these will be given hereafter.

The larger, and more interesting, portion are the grave-stones or coffin-lids, with crosses of different devices cut upon them. They had evidently been used indiscriminately with other materials for the outer facing, as well as for the internal filling up, of the walls, and especially in the foundations of the tower-piers, and north transept. One had been cut to suit the outline of a half pillar, and mouldings of windows had been worked on the reverse side of others. Some time elapsed before these ancient grave-stones attracted notice, and many had in consequence been used again in the foundations of the new walls. Fortunately a considerable number have been saved, and are placed, for the present, in the church porch; several smaller ones also have been at different times preserved by a gentleman living in the neighbourhood, and are deposited in his very valuable museum of local antiquities. Mr. Bateman has liberally allowed drawings to be taken of such in his possession as were required to make up the series of different designs, and has kindly furnished much useful information respecting them.

The collection, now to be seen in Bakewell church, consists of parts of fifty-seven grave-stones, several of which are nearly entire, and of considerable size, together with five head-stones. About eighteen, I believe, including several head-stones, are in Mr. Bateman's possession. A few others of less importance are to be seen in the pavement of the church; thus making altogether upwards of seventy examples. It is believed to be by far the largest and most varied collection existing in any church in England; indeed, not a third part of this number can probably be seen elsewhere; some of them being probably unique examples, and very few moreover duplicates of the same design. But large as this number is, I was assured by the workmen that at least four times as many had been used again in building the new walls. It will be borne in mind, that it has been shewn that all these are probably prior to c. 1260, and a considerable number prior to c. 1110. A selection only of the more remarkable of these crosses can here be given.

There can be little doubt that many of these stones had been placed over graves in the church-yard. We now most frequently find them only in the pavement in the interior of our older churches: those in the open ground having perished, through exposure. But the large number here found, could not all have been intended to be laid in the pavement of the church. Six slabs, similar to these, may be seen lying in the church-yard of Chelmorton, about seven miles distant, with every appearance of being in their original place. Others also have been dug up in the church-yard at Darley. May not those which were found in the foundations of the tower and north transept, have covered graves which might be disturbed when that part of the church was built; and may not those of later date have belonged to graves previously existing on the site of the Newark? And may they not in both cases have been used in the construction of the edifice, not so much for the sake of the material, as from a wish to preserve whatever might have been connected with religious uses: just as we know, that relics of other kinds have been often secreted, by being built up in the walls of churches? At Darley, portions of seven crosses of this kind may be seen built into the wall over the east window of the chancel, and other parts of the church. And no doubt many other instances of similar preservation of ancient tomb-stones may be found in the retired village churches in Derbyshire, as well as in other parts of the country. Several examples indeed of interesting fragments thus built into the walls of churches have been already noticed at different times in the Archæological Journal, and other publications.

These ancient grave-stones are interesting to us on several accounts: they seem to furnish decisive evidence that such memorials of the dead were in more general use at an early period, in some parts of the country at least, than is commonly supposed. We most frequently find them in the present day only in the interior of churches, and we are apt, on that account, to infer that they were used almost exclusively to mark the burial-place of those who belonged to the higher ranks in the community; the knight, the ecclesiastic, the staple-merchant, or those who for some special reason may have been thought entitled to burial within the consecrated building. But the very large number found in this church, in a remote and thinly inhabited part of the country, as mountainous districts at that time usually were; the rudeness of design in some, and the difference of size in others, would lead us to conclude that such monuments must have been used, more or less, for persons of nearly every condition. This remark, however, ought perhaps to be restricted in some measure to the inhabitants of the hilly parts of the country, especially in the northern counties, where abundance of stone might be procured at little cost. And this last consideration will also suggest a reason why these incised stone crosses should have been retained to a much later period in some parts of the country than in others, after the use of brass or latten had been generally introduced.

This collection also presents a great variety of marks, or symbols, indicative of the profession or trade of the deceased, several of which have been already referred to in the previous description. Some of these are well known, such as the sword and chalice, the shears and bugle-horn; examples of which may be seen in Gough's Sepulchral Monuments, and Lysons' History of Cumberland: others are rare, such as the key, and some which were too imperfect to be satisfactorily made out. It is well known that shields with armorial bearings were not introduced upon tombs till a later period. The use of such symbols is of very high antiquity: for examples are by no means uncommon on Roman tombs combined with inscriptions: and it seems to be admitted, that many of the devices on the monuments of the early Christians, in the catacombs at Rome, which have been considered by some as emblems of their martyrdom, refer rather to their occupation than to the instruments by which their tortures were inflicted; (see Maitland's Church in the Catacombs.) May it not have been the case, that in an unlettered age such symbols supplied in a great measure the place of inscriptions, which at that period would have been unintelligible to the majority of the survivors of the deceased. Indeed, it deserves notice, that examples of sepulchral crosses of the eleventh and twelfth centuries marked with inscriptions, are seldom met with in England. A few have been found in Yorkshire and the northwest counties, but they are rare: and this does not seem to be always affected by considerations of the rank of the individual, as it applies to the tombs of the ecclesiastic, and the knight, as well as of others. When inscriptions were added, they were more frequently cut by the side of the stem or shaft of the cross, than on the margin of the stone, as was usual at a later period. Exceptions may doubtless be found, as on the celebrated tomb of Gundrada at Lewes, supposed to be early in the thirteenth century, in which the inscription is cut both on the sides, and along the middle of the slab, (see Gough.) It is remarkable, however, on the other hand, that in Ireland, where, according to Mr. Petrie's valuable work, examples of monumental crosses are to be seen of far higher antiquity than any in England, some being referred to the sixth or seventh century, nearly all are accompanied with inscriptions; and these more frequently by the side of the shaft, or in the head of the cross, than on the margin of the stones. This difference is singular, and well deserves further investigation.

Again, the large number of examples brought together in this collection, present a better illustration of the progress of the art of design in such monumental crosses, than can be seen elsewhere. We may here trace at one glance the successive varieties of form, gradually developed from the simple intersection of two straight lines, rudely cut, to the delicately foliated designs in relief, which in their turn gave way to the yet more elaborate devices, which the use of brass or latten had facilitated in the thirteenth century.

It may be as well to notice, though indeed it is sufficiently obvious, that nearly all the varieties in the design of these crosses may be reduced to three elementary forms; the two last being, in fact, only modifications of the first.

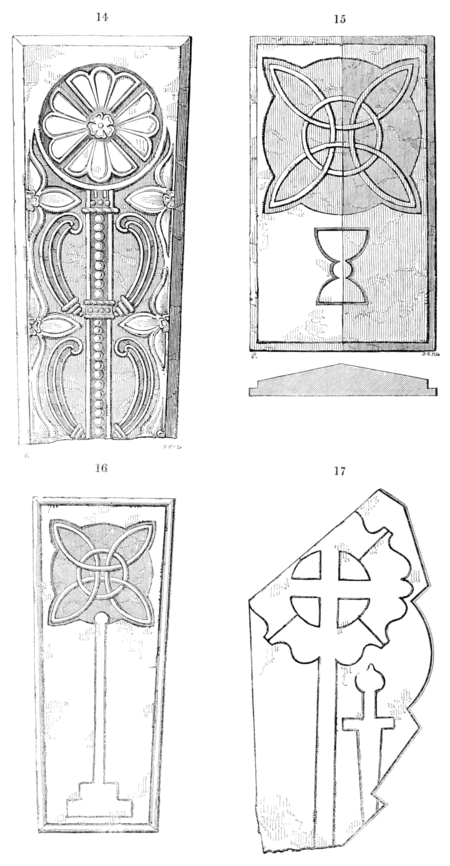

1. The simple intersection of two straight lines, with ornaments added to the extremities, (the most common being in the form of a fleur-de-lys,) or at the sides, or point of intersection, where it is enlarged, and the arms of the cross shortened, as in the common cross fleury. No. 18.

2. The expanding the extremities of the arms till they nearly meet, as in the Maltese cross, producing a figure, supposed by some, intended to represent the nimbus, or glory, such as we see in old paintings round the head of our Lord. Some of these examples will shew how this solid figure gradually became lighter, and assumed the graceful form of foliage. See Nos. 12 and 24.

3. The introduction of an additional member from the point of intersection of the arms of the cross, thus forming a figure with eight members instead of four, as in Nos. 11 and 13. In some varieties the vertical and horizontal members are re moved, and only the intermediate ones left, as in No. 16; but these are of rare occurrence. Examples with six members, instead of four or eight, are still more rare, as No. 7. Some irregular varieties, as Nos. 4 and 8, can hardly be reduced to any rule.These remains are also interesting as shewing the early use of head-stones with the sacred symbol cut upon them, being probably among the oldest examples yet discovered in this country, and in greater number and variety than has yet been noticed.

Of these head-stones, Nos. 1, 2, 3, 5, are in Mr. Bateman's possession; they are rudely cut, and appear to be of very early date. No. 4 is an ancient form of the cross, of which probably the device upon No. 16 of the flat grave-stones may be considered to be a modification, and of which many examples, both with and without circular bands, and with a great variety in the detail of their ornaments, may be observed in Norman carved work; as in St. Peter's church at Northampton, before alluded to, the nave of Rochester cathedral, and some other of the older churches. It would be an interesting subject for enquiry, whether this form of cross, which resembles what is commonly called a St. Andrew's cross, may have had its origin in the Greek letter X, as used in the abbreviation of the name of our Lord from a very remote period. It is certainly remarkable that the device which is cut upon a large portion of the earlier tombs in the catacombs at Rome is not the cross, but the sacred monogram, composed of X and P, the two first letters of Χριστος. And in some later examples a kind of short shaft is added, so as to resemble in some measure the form of the cross, and the whole figure surrounded by a wreath or circle. Nos. 2, 6, have the same device on both sides. No. 7 is represented somewhat too large, being about the size of No. 6.

These stones have been considered as head-stones, because it seemed most probable they had been used for that purpose. It ought however to be stated, that about the period to which they maybe referred, crosses were sometimes placed at the foot of the grave as well as at the head. Some examples of head-stones, with inscriptions upon them as early as the sixth or seventh century, are said to exist in Ireland.

- ↑ The Saxon name baꝺecanwillan, or Baꞇhecanwell, i. e. the bathing well, is obviously derived from its baths, which were known by the Romans. In the Doomsday Survey and other early documents it is called Badequelle and Baucwell. See Glover's Hist. of Derbyshire. A work containing much valuable local information, which it is to be regretted is not yet completed.

- ↑ The new work is in most respects a faithful copy of the building taken down, with a few judicious alterations. It has not been attempted to restore the transepts to what might he conjectured to have been their original design, for such a restoration to have been made complete would no doubt have been attended with many difficulties. The tower pillars have been strengthened, and made to correspond in design with the south transept, and the work appears to have been executed in a very substantial manner. It should be observed that the triangular lights which are inserted over the side windows of the south transept did not exist in the former building.