Encyclopædia Britannica, Ninth Edition/Anchor

ANCHOR, in Navigation, from the Greek ἄγκυρα, which Vossius thinks is from ὄγκη, a crook or hook, an instrument of iron or other heavy material used for holding ships in any situation in which they may be required to lie, and preventing them from drifting by the winds or tides, by the currents of rivers, or any other cause. This is done by the anchor, after it is let down from the ship by means of the cable, fixing itself into the ground, and there holding the vessel fast. The anchor is thus obviously an implement of the first importance in navigation, and one on which too much attention cannot be bestowed in its manufacture and proper construction, seeing that on it depends the safety of the vessel in storms. The invention of so necessary an instrument is to be referred, as may be supposed, to the remotest antiquity. The most ancient anchors consisted merely of large stones, baskets full of stones, sacks filled with sand, or logs of wood loaded with lead. Of this kind were the anchors of the ancient Greeks, which, according to Apollonius Rhodius and Stephen of Byzantium, were formed of stone; and Athenæus states that they were sometimes made of wood. These sorts of anchors retained the vessel merely by their inertia, and by the friction along the bottom. Iron was afterwards introduced for the construction of anchors, and also the grand improvement of forming them with teeth or flukes to fasten themselves into the bottom; whence the words ὀδόντες and dentes are frequently taken for anchors in the Greek and Latin poets. The invention of the teeth is ascribed by Pliny to the Tuscans; but Pausanias gives the merit to Midas, king of Phrygia. Originally there was only one fluke or tooth, whence anchors were called ἑτερόστομοι; but shortly afterwards the second was added, according to Pliny, by Eupalamus, or, according to Strabo, by Anacharsis, the Scythian philosopher. The anchors with two teeth were called ἀμφίβολοι or ἀμφίστομοι, and from ancient monuments appear to have been much the same with those used in our days, except that the stock is wanting in them all. Every ship had several anchors, the largest of which, corresponding to our sheet-anchor, was never used but in extreme danger, and was hence peculiarly termed ἱερά or sacra; whence the proverb sacram anchoram solvere, as flying to the last refuge.

Up to the commencement of the present century what was termed the "old plan long-shanked" anchor seems to have been generally used. It was made of wrought iron, but the appliances of the anchor smith were so crude that little dependence could be placed upon it. About this time public attention was drawn to the importance of the anchor by a clerk of Plymouth yard named Pering, who published a book, and argued, from the number of broken anchors which came to the yard for repair, that there "must be something wrong in the workmanship—undue proportion or the manner of combining the parts." Mr Pering altered the sectional form, made the arms curved instead of straight, used iron of better quality, and introduced improvements in the process of manufacture. Since 1820 about 130 patents have been taken out for anchors; and the attention thus given to the subject, with the introduction of steam hammers and furnaces, the substitution of the fan blast for the old bellows, and the better knowledge obtained of the forgeman's art, have rendered the anchor of the present day so far superior to that of fifty years ago, that we rarely hear at one being broken, the ground in which it is embedded generally giving way before the anchor.

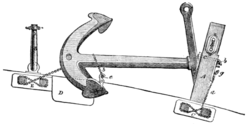

Fig. 1.—Common Anchor. Fig. 2.—Admiralty's. Fig. 3.—Rodger's.

1.— Chain and Anchor: for Steam Vessels required by Lloyd’s Register of British and Foreign Shipping (1874).

| A table should appear at this position in the text. See Help:Table for formatting instructions. |

2.—Chains and Anchors for Sailing Vessels required by Lloyd’s Register of British and Foreign Shipping (1874).

| A table should appear at this position in the text. See Help:Table for formatting instructions. |

1 The rules for the building and classification of iron ships provide that "their equipment is to be regulated by the number produced by the sum of the measurements of the half moulded breadth of the vessel amidships, her depth from the upper part of keel to the top of the upper deck beams, and the girth of her half midship section to the same height, multiplied by the vessel's length, for a one, two, and three decked vessel, and for a spar-decked steam vessel."

2 Two of the bower anchors must not be less than the weight set forth above; in the third a reduction of 15 per cent. will be allowed.

| A table should appear at this position in the text. See Help:Table for formatting instructions. |

Weight of Anchors supplied to Boats.—42 ft. Launch, 120 ℔; 32 ft. Pinnace, 56 ℔; 30 ft. Cutter, 40 ℔; Jollyboats or Gigs, 30 ℔.

The stock is made of iron in anchors of 60 cwt. and under, and of wood for anchors above that weight. A wooden stock (fig. 8) is made of English oak in two pieces; they are scored over the square so as to leave a space of about 2 in. clear between them at the shank and to touch at the extremities. It is made parallel for about 16th of its length at the centre, tapering from thence to the extremities, the side next the shackle being kept straight and the remaining three sides tapered. The section at any part is square, the dimensions being 110th of the length at the centre and half of this at the ends. The two pieces are fastened together by four iron bolts near the shank, six or eight treenails, au11 six iron hoops at the ends. The hoops are driven on tightly while hot, so that the contraction of the iron in cooling may draw the parts closely together. A projection, termed a nut, shown by the dotted lines at a,a, in fig. 8, is left on the square to prevent any lateral motion of the stock. An iron stock is made in one forging, so as to pass through a hole a, punched in the square. The stock has a shoulder b, which fits against the side of the shank when it is in the position for action as in fig. 1, and it is secured by a key driven tightly on the other side of the shank. The advantage of this is, that the stock can be unshipped and laid along the shank for convenience of stowing, as shown in fig. 4. The weight of the stock, whether of wood or iron, is about 16th that of the anchor.

Fig. 4.—Iron stock unshipped for stowing.

The shank and each arm are forged under the steam-hammer in three pieces, and are then welded together at m and n, fig. 8. The welding is done by the "Hercules," which is a heavy iron ram placed over an anvil, so that it can be raised by steam power to a height of some 9 or 10 feet, and then let fall, being guided in its descent by three men, who hold rods attached to it. It is needless to say that the welding must be carefully done, as the whole strength of the anchor depends upon it.

To ensure safety, every anchor should be tested at a public testing house to 13d of its breaking strain. The anchor is held by a chain attached to the shackle, and the strain is applied to each arm separately at 13d of its length from the point. The proof of the anchor is that it must show no sign of fracture, and that if any deflection is caused by the strain, it must return very nearly to its original shape. A good anchor, after being deflected half an inch, will return to its former shape, leaving no permanent set.

The size of anchors for various ships has been determined by practice, but is based upon the theory that as the anchor is required to withstand the force brought upon the ship by the wind and tide, which would otherwise cause her to drift, its strength must be nearly proportional to her resistance. A result which will accord with sound practice may be obtained by calculating the resistance of a given ship at a speed or twelve knots, and taking this tor the working load of the anchor. The working load should be half the testing strain, and consequently 16th of the breaking strength.

The tables on pp. 4 and 5 give the sizes and number of anchors and cables carried by ships of the Royal Navy, and those required by Lloyd's rules to be carried in merchant ships. The sheet and bower anchors are of the same size, and are given in the tables under the heading “Bower.”

Public attention having been directed to the subject of anchors by the specimens which were exhibited at the Exhibition of 1851, a committee was appointed by the Admiralty in the succeeding year to consider and report upon the qualifications of the various kinds. The committee determined the qualities it was desirable for an anchor to possess, and assigned numerical values to each. The following tables give the result of their labours, showing the number of marks obtained by each anchor under trial:—

Table showing the relative order in which the several Anchors stand with regard to each of the properties essential to a good Anchor—the names arranged alphabetically.

| A table should appear at this position in the text. See Help:Table for formatting instructions. |

Table showing the estimated numerical values of the several Anchors in regard to the properties considered essential to a good Anchor.

| A table should appear at this position in the text. See Help:Table for formatting instructions. |

Note.—This Table only professes to show approximate values, and has no pretensions to mathematical accuracy or precision.

The following is a recapitulation of the order in which the anchors were ranked by the committee, together with their relative percentage of inferiority or superiority in the Admiralty anchor, the value of which, as given in the foregoing table (18·17), was taken as the standard or unit:—

| A table should appear at this position in the text. See Help:Table for formatting instructions. |

The decisions of the committee have been much questioned, one of the objections being that the qualities of strength and holding on, neither of which is of any use without the other, were assigned such different values as 15 and 80; it has also been stated that the Admiralty anchor was treated unfairly, as one was taken promiscuously out of store for the trial, whereas the other competing anchors were made specially for it.

The Admiralty anchor (fig. 2) differs only from the ordinary anchor in having a nut, a, worked on the square, so that a wooden stock may he fitted temporarily if the iron stock is damaged, and that its proportions and form have been carefully considered and definitely fixed. Lenox's and Aylen's were modifications of the Admiralty anchor. Mitcheson's was of a difficult section to forge, and consequently expensive, and was withdrawn from the test of strength. Isaac's was of a peculiar construction, and may be passed over as more curious than useful.

Rodger's anchor, placed second on the list, was one of Captain Rodger's, R.N., who for the last forty years has devoted considerable pains to the improvement of anchors. Among his earlier inventions is an anchor with a hollow shank, to obtain greater strength with a given weight of iron; then an anchor without a palm, which he termed a “pickaxe anchor;” afterwards a “small-palmed” anchor; and by a patent taken in 1863, an “indented small-palmed anchor” (figs. 3 and 7). The stock is of iron in large as well as small anchors, and is made with a mortice, to fit over the shank instead of passing through it. It is somewhat heavier than the stocks of other anchors; the arms are shorter than usual in proportion to the length of the shank, and are of a wedge shape, varying in sharpness from the throat to the head of the palms; the back part of the arms is parallel from palm to palm; the palm is double concave on the front, and has a small border at the edge for confining the soil through which it is dragged; it also has a large indentation on the back for the same purpose and to save weight; the shank is rectangular at its junction with the arms, and square close to the collar for the stock; the crown is made longer than usual, and has a large countersunk hole in its centre to save weight. 11 is claimed for this anchor that the peculiar form of the palms and arms, with the hole in the crown, give it great holding power, and that it will bury itself in the soil until the upper palm is beneath the surface, and consequently is not liable to be fouled by the cable.

Fig. 5.—Trotman's anchor.

Trotman's anchor (fig. 5), which obtained the highest place in the committee's estimation, was an improved Honiball's (Porter's). The stock is of iron, similar to the Admiralty anchor; the shank is of rectangular section, somewhat larger in the centre than at the ends, and is made fork-shaped at one end to receive the arms; the arms are in one piece, and are connected to the shank by a bolt passing through their centre. The peculiarity of the anchor is that the arms pivot about this bolt, so that when it takes hold the upper fluke is brought in contact with the shank, thus reducing the height above ground, and rendering it almost impossible for the cable to get entangled round it, or, in other words, for the anchor to become foul.

Fig. 6.—Martin's.

we nmv come to nn anchor or entirely tlitlerent ah.-ipe shackle of the nnellor, nnd the long link plncod over the Iwhrm from the premliiw ]v'.LN¢ullN.' by nFl-ellchnmunninetlllartill. The nnchnr i. prcscllwti in tag 6 in the 1 ml in which it lies on the gronntljnst belore tnking held. The i-ihnnlt is unlde in one lerging, is of rectnngnlnr sealion, having in shoulder fax the Fm ¢—M-r'-n'vstuck to ht against, and is increased both in thleknm Lulli arm at the crown; the nnns with tho pnhns nrc [urged in one piece, and then bent to the mpiiied snipe; one of the nrms is passed through a hole in the crown ninl is hcpt in poisitiun by it [to]: iorewcd through the no 7 —now«A-whar.nua an-nnerommving. and at the crown, so that its point reaches a little my belt. II,' it is than erl over a dent _q, on the side of the into nu indent lnlule for it in the round part at the hack catllenil, and hrcinycil at the hnlhmls C4 The end. of the hi the itruls. 1'util lufy recently this securing hnlt was ilnrnlc painter is [xlsued under the croivn and over the phlcctl in the thinlt in -.t rcitieal position (supposing the shank; its long link is placed liver the belt e, and it is nnchor to be lying with the palnis hm'11.ont.-ll), so as to cut behlyerl it the boilnrds 131 when it is desired to let go into the hollow pert at the front of the bent nun A very the onchor, the nrm is shipped ntf, nnd the lnnynrtls atf strong shoulder is \\'0l'i(cv.i on the arms, so as to it in a and d nre mnnned; then. it the word of ooniilmnd (given, move an (inn side of the shank, in such 2 lmlnner that if the ship is rolling, when she lurches towards the side the anns will revolve through an nngle of 30" either why. on which the anchor is storrtd), the nmn pnu Lhe L-lnyurds, The stack is fitted over the shank is shown, and secured and Il and cam relensell simultaneously, the links of the ily e key, which fixes it lightly clgilinst the shoulder lell: ult—stoppei' But' shnnl; painter drop 4211', end the anchor Uh the shzulkl The ntlrentnges of!\[lu1ill'a anchor are is tall: elenr of the 1. In nierehnnt ships it is notnsnal to fulluuix-—It is relfnccttiilg; it ninst tall in the position lit the secuml nhpntopper, b and c,- in this case it is notchtlicnrn In the figure, nnd the weight of the Mills, together snry, hcrorc letting gn, to -'toels.hill" the:inehor,—thnt with the pull oi the enhie, presses their sharp points inte is, tn ease mruy the shank painter, so thnt the anchorlmnge the soil, to tlint it takes hold inuuedintely; it is impossible by the enthend alone. The next thing is to "\vt:igh" the to foul it; it stairs much more neatly thnn any other nnehar. Itishove up by the tstpstnn, and when it nppnsis zmchor; its holding power is rery grent, ns both nrnir ore nt the hnn-s, the npcmtions nl U cutting -' anti "fishing -' in the sail zit the mule tinle, mid the stock, which is flat. hnvn to he peifornlcl], A chain ciillell the " mt pendant" nnd brottd, adds iimmriafly to this qulllity; the strength is is mve o\'I:r the slleavo It in the eethnncl, and ishnclsled ta aha my gt-one AI: an experiment lnadc at Portslllolflil nshort picce oi at similar nhnin attnclinl to the anchor nt iluckyllxd in Mrlrcli IBG7, twa ol the lmchuxs were sub one end, and stoppercd to the cable at the other; the injoctcd to at strain of 50 per cent. over the Admiralty proof; board and of the cal pendant: is taken to 2 iciltiihg hlock the arinsirore deflcctctl hut three-tellths ctr itn ilu:ll by this run the opposite ride or the ship, and n purchnse tackle great strain, llud nlinn it wancenioted tlinyregiincd their ntmched to it, so its to give the nten a run right ntt. renner shnpe. The nnoher is ntntle in three separate when on is rendy, the word is given, anrl the men rim hlrwngs ivithuut ti wullh Uunutstcd turret shim, which any with the [lIIl'('h.8se until the anchor hangs from the 1 \'cnna1i—rmllld hie, an.-, ainiostuithmlt enception,httnt1 cethc-ail instead or the hm\se—}-ipe; it istllcn said tn be with Harlin': anchor on account of the neutnms with " ent1ed." A chain rave through the block in. the hem! of nhich it cnn he stewed, ns the stock oi nny other iulchur, the iish ilarit, and llavillg ti la _ hook at the end, is than if not ullshipped, xmuhl obstruct the fire of the guns The hooked to the inner am hi the anchor, which is then Atlniiialty allow -'1 necluetien of 25 per cent, in wtig tier irlisell and swnng inhourd (the ssh tlntit heing made to l\I.1rtin's anchor, using all 80 cut ~irtin "here 2 90 owl. l'k'\'0i\'C), so til I: the fluke rests upon the hill-beard D, and _lthniralty or Itntlgerln nnehor, weighing with its stoclr the nnchur is fished." The entvsttimwralld shank painter min 10:! tn 112 cnt, nenld be fitted, the weight given are then rave, and nll made ready to let go ngnin it in fur )[ztniu'tl anchor including the wick. molnelltls notice. tonnes. Smitll'sp:1entstocklessnnchrlrlmslxzen highlyspokonol.

Fig. 7.—Bower Anchor, and manner of stowing.

The cathcad 5i10\\'I in the iignre is mile or plat/ms inlrl her. It tsain-dilicntion Uf Manilfsnllclior, hutlvithmlttllcstueh. angle irons, nrnl is silllihll' in shape tn the nld wooden ent. mpg A bower author is stuwetl ill'll.)I. service as sliown ill lleads; it is fitted with:4 single sheave It, made to swivel Hex ng. 7. 4', is the ell!/LMII,- ]3,Ihc_fi.~ll tlrlvfl; u, lintl E, bnl- sons to give a Llir leml tor the chain nhen the anchor is av. Itnvk, D, the mt.l.xn-4. The anehor is held in plnce by it the hen pipe. cathoads are trerpnntlyinnne ol solid two clhiins, <1 and 1., termed the MI-.!lo])])rr null sIcrnil- lnrgingn, with n hlnck linnging from the head for the cal. ]><li!tlt'I' l'Lpl:cti\'cly, each or nhicli is tith~,tl with a long penthint or t':t1L In ships dcaigllmi tor mnuiling, the catlink at one end. A bolt I», about 5 or 6 inches long, is 'hc:l<1 is ninth: to revolve like the fish dnxit B, so that it [mid on the side of the mthend, on a hinge at its lmier can he turned inboard, and then: will be no projection on end; it is hchl in the in. v1 t ptlsiliull by mluihcr holt 1', the bow to foil] the snen. rigging.

Fig. 8.—Stowing a Sheet Anchor.

ii should he obserred rhac whenever a slip-stollpt-I is iiiood, eure nrusc \le_1.a.kE\, hy placing's [will in the baeh oi it, or otherwise, to prevent the anchor being let go by accident.

Stern and scrranr anchors are skewed at the stem of the ship in the way described ior shoot snrhors.

The kedge lmchon are genemily slowed in die rnsin. chains.

Sheet, scream, and sieru anehors being very rarely used, hlwe I/0 he re—slc\\'ed hy ihe uid oi the yordsirrn, \vii.hollt any speoinl appliunees being iiuod.

Fig. 9.—Buoy Mooring Block.

Fig. 10.—Cast-iron Mooring Anchor.

Fig. 11.—Mushroom Anchor.

1[rm1'7r_a one/um are thnse which are pliwed in harbours, &t:,fo1 ihe eonrenienee oi resels irequeniing ihern. A large buoy is iittacheii to the end or ihe mooring oahle,sud the ship is made iusi to u ring—holi fitted on the buoy. Mooring uueluns are not limikwl by oousideraiions oi \vl:igIlt, Aim, as oiher uuohnrs sre, she only requirements being ehai ihey have snllicient holding powcr, and do uoi pmjeci. above are gmmrd, us any prnjcction in ihe shallow waters in whieb they nro usually placed would render ships lishle be injury from gmunding on them, and be dungomus to flshingenuls, iie. Mooring lxllchors may thereioro be oi stone, as shown in fig. 9; oroi mssiion, as in m-s.—Bu->yr-rm smu . fig. 10. Mimhmom snehors (fig. 11), insi proposed ior ships, ore nuw only used ior nllmrings. An old anchonvhich has one arm dun» aged is frequently used as u mooring anchor, Lhe dauiaged nrmheingbcntdown elose to the shrink; the anchor in sunk win. the beni ann uppermost, nnd more is no pmjueueu zllwve the ground. In llaxbuuni where there is not much room it is usual in phwe luo imchols, connected by a cable, in a line at right imglrs to «he direction of the tide; a swivel is filled at ihe cclltre oi this cable, mid Ihe buoy ehain is made lash to «ho su with ihis ill-l-alignment. the ship does not (sweep such a llnge circle in siiinging.

Fig. 12.—Mooring Anchor.

The hes-i muoring anchor uhieh has yei been devised is shouu in fig, 12. us shank is around bar oi llrroilght iron, (1, about 7 II: .\n length and 6 inches in ' iliillllckur; it is inurellscd zit'll 10 9 inrhcs dinlilmer run about 1 foot oi its length, and renuineieri ai fsiiuilarly to the piaint oi il. giuilct; holes ure nude in die stolltlmrt b, and a icm\v flange oi 3; tool diaineier in ms! nmunil ii; the uloikcll mom! gets into the holes rad makes it. good oonnho on,~,,,_,2 .,m,i,,g uiih the \Vl'DlI§1!t>iIUll ch k. A su L Aulror, r, in which u Inigo slieehle (I, is attnchtil, is filtcd on as shown, uud secllmd by u zitmng nut; the and oi iho shauh z is uiude square, To nlaeo this mcllox in alnnu's iaihonis oi u-uier, {our iron imis, oaeh about 17 ilei in lvugtll, and provided with n socket or one end and o sqniim head us the other, are used. As the nllchm is lowered the socket. of the filst bar is fitted on at 9, and the socket of the second bar in us iuru fittcd lo the square end of the iirsl, and so on iii! the anchor miichcs the bottom, A dnmillcad, simihu ion L'{Ap.\I1Il, is then mm! on tho lusi.1iar,aiui caps-iuu burs shipped in it; by chose nlczins the mu-llor is iurned round, Luld:50 son.-uud into the _gruumL It must he sunk thmugh the bait mud or sand into the Imriicr soil bcncslll it, imd when this is done the holding llowuxoi' ihezmchor is enormous Ali anchui af the dinlcnbimis given weighs about 14 en-i., and will hold iar more ihuu u oasi-iron mooring onehor oi 1 tons. The only objections io ii seem to be the dhheuliy oi removing it ii are muurillgs are required to be when up, and that spcrial annlisnees use l-uluimd ior putting it down.

A good anchorage is where ihere are iron. io lo 20 Anrhnng iaehoois of water, and rhe gmlmd is not mcky or loose sand. where ihere are more llmII:1'l10\lt20 iiithmns we cable bours too ooorly poipoudioulur, uud is liable in hip ihe anchor. For anchoring in ordinury uoailioriliuleuglb oi mble veered our is ahoui thxec timis ibe depth oi wallet.