Encyclopædia Britannica, Ninth Edition/Thermodynamics

THERMODYNAMICS. In a strict interpretation, this branch of science, sometimes called the Dynamical Theory of Heat, deals with the relations between heat and work, though it is often extended so as to include all trans formations of energy. Either term is an infelicitous one, for there is no direct reference to force in the majority of questions dealt with in the subject. Even the title of Carnot's work, presently to be described, is much better chosen than is the more modern designation. On the other hand, such a German phrase as die bewegende Kraft der Wtirme is in all respects intolerable.

It has been shown in a previous article (Energy) that Newton's enunciation of the conservation of energy as a general principle of nature was defective in respect of the connexion between work and heat, and that, about the beginning of the present century, this lacuna was completely filled up by the researches of Rumford and Davy (see also Heat). In the same article Joule's experimental demonstration of the principle, and his determination of the work-equivalent of heat by various totally independent processes, have been discussed.

But the conservation of energy, alone, gives us an altogether inadequate basis for reasoning on the work of a heat-engine. It enables us to calculate how much work is equivalent to an assigned amount of heat, and vice versa, provided the transformation can be effected; but it tells us nothing with respect to the percentage of either which can, under given circumstances, be converted into the other. For this purpose we require a special case of the law of transformation of energy. This was first given in Carnot's extraordinary work entitled Reflexions sur la Puissance Motrice du Feu, Paris, 1824.[1]

The chief novelties of Carnot's work are the introduction of the idea of a cycle of operations, and the invaluable discovery of the special property of a reversible cycle. It is not too much to say that, without these wonderful novelties, thermodynamics as a theoretical science could not have been developed.

Carnot's work seems to have excited no attention at the time of its publication. Ten years later (1834) Clapeyron gave some of its main features in an analytical form, and he also employed Watt's diagram for the exhibition of others. Even this, however, failed to call attention properly to the extremely novel processes of Carnot, and it was reserved for Sir W. Thomson (in 1848, and more at length in 1849) to point out to scientific men their full value. His papers on Carnot's treatise, follow ing closely after the splendid experimental researches of Colding and Joule, secured for the dynamical theory of heat its position as a recognized branch of science. James Thomson, by Carnot's methods, predicted in 1849 the lowering of the freezing point of water by pressure, which was verified experimentally in the same year by his brother. Von Helmholtz had published, two years before, a strikingly original and comprehensive pamphlet on the conservation of energy. The start once given, Rankine, Clausius, and W. Thomson rapidly developed, though from very different standpoints, the theory of thermodynamics. The methods adopted by Thomson differed in one special characteristic from those of his concurrents, they were based entirely on the experimental facts and on necessary principles; and, when hypothesis was absolutely required, attention was carefully directed to its nature and to the reasons which appeared to justify it.

Three specially important additions to pure science followed almost directly from Carnot's methods: (1) the absolute definition of temperature; (2) the thermodynamic function or entropy; (3) the dissipation of energy. The first (in 1848) and the third (in 1852) were given by V. Thomson. The second, though introduced by Rankine, was also specially treated by Clausius.

In giving a brief sketch of the science, we will not adhere strictly to any of the separate paths pursued by its founders, but will employ for each step what appears to be most easily intelligible to the general reader. And we will arrange the steps in such an order that the necessity for each may be distinctly visible before we take it.

1. General Motions. The conversion of mechanical work into heat can always be effected completely. In fact, friction, without which even statical results would be all but unrealizable in practical life, interferes to a marked extent in almost every problem of kinetics, and work done against friction is (as a rule) converted into heat. But the conversion of heat into work can be effected only in part, usually in very small part. Thus heat is regarded as the lower or less useful of these forms of energy, and when part of it is elevated in rank by con version into work the remainder sinks still lower in the scale of usefulness than before.

There are but two processes known to us for the conversion of heat into work, viz., that adopted in heat engines, where the changes of volume of the "working substance" are employed, and that of electromagnetic engines driven by thermoelectric currents (see Electricity, vol. viii. p. 96). To the latter we will not again refer. And for simplicity we will suppose the working substance to be fluid, so as to have the same pressure throughout, or, if it be solid, to be isotropic, and to be subject only to hydrostatic pressure, or to tension uniform in all directions and the same from point to point.

The state of unit mass of such a substance is known by experiment to be fully determined when its volume and pressure are given, even if (as in the case of ice in presence of water, or of water in presence of steam) part of it is in one molecular state and part in another. But, the state being determinate, so must be the temperature, and also the amount of energy which the substance contains. This consideration is insisted on by Carnot as the foundation of his investigations. In other words, before we are entitled to reason upon the relation between the heat supplied to and the work done by the working substance, Carnot says we must bring that substance, by means of a cycle of operations, back to precisely its primitive state as regards volume, temperature, and molecular condition.

2. Watt's Diagram.—Watt's indicator-diagram (see Steam-Engine) enables us to represent our operations graphically.

Fig. 1.

For if OM (fig. 1) represent the volume, at any instant, of the unit mass of working substance, MP its pressure, the point P is determinate and corresponds to a definite temperature, definite energy, &c. If the points of any curve, as PP, in the diagram represent the successive states through which the working substance is made to pass, the work done is (loc. Cit.) represented by the area MPP M . Hence, a cycle of operations, whose essential nature is to bring the working substance back to its primitive state, is necessarily represented by a closed boundary, such as PP Q Q, in the diagram. The area enclosed is the excess of the work done by the working substance over that spent on it during the cycle. [This is positive if the closed path be described clockwise, as indicated by the arrow-heads.]

3. Carnot's Cycle.—For a reason which will immediately appear, Carnot limited the operations in his cycle to two kinds, employed alternately during the expansion and during the compression of the working substance. The first of these involves change of volume at constant temperature; the second, change of volume without direct loss or gain of heat. [In his hypothetical engine the substance was supposed to be in contact with a body kept at constant temperature, or to be entirely surrounded by non-conducting materials.] The corresponding curves in the diagram are called isothermals, or lines of equal temperature, and adiabatic lines respectively. We may consider these as having been found, for any particular working substance, by the direct use of Watt's indicator. It is easy to see that one, and only one, of each of these kinds of lines can be found for an assigned initial state of the working substance; also that, because in expansion at constant temperature heat must be constantly supplied, the pressure will fall off less rapidly than it does in adiabatic expansion. Thus in the diagram the adiabatic lines PQ, P Q cut the lines of equal temperature PP, QQ downwards and to the right. Thus the boundary of the area PP Q Q does not cross itself. To determine the behaviour of the engine we have therefore only to find how much heat is taken in along PP and how much is given out in Q Q. Their difference is equivalent to the work expressed by the area PP'Q'Q.

4. Carnot's Principle of Reversibility.—It will be observed that each operation of this cycle is strictly reversible; for instance, to take the working substance along the path P P we should have to spend on it step by step as much work as it gave out in passing along PP, and we should thus restore to the source of heat exactly the amount of heat which the working substance took from it during the expansion. In the case of the adiabatics the work spent during compression is the same as that done during the corresponding expansion, and there is no question of loss or gain of heat directly.

If, however, a transfer of heat between the working substance and its surroundings have taken place on account of a finite difference of temperature, it is clear that such an operation is not reversible. Strictly speaking, isothermal expansion or contraction is unattainable in practice, but it is (without limit) more closely approximated to as the operation is more slowly performed. The adiabatic condition, on the other hand, is more closely approximated to in practice the more swiftly the operation is performed. We have an excellent instance of this in the compression and dilatation of air caused by the propagation of a sound wave.

And now we have Carnot's invaluable proposition, a reversible heat-engine is a perfect engine, perfect, that is, in the sense that no other heat-engine can be superior to it. Before giving the proof, let us see the immense con sequences of this proposition. Reversibility is the sole test of perfection; so that all heat-engines, whatever be the working substance, provided only they be reversible, convert into work (under given circumstances) the same fraction of the heat supplied to them. The only circumstances involved are the temperatures of the source and condenser. Thus we are furnished with a general principle on which to reason about transformation of heat, altogether independently of the properties of any particular substance.

The proof, as Carnot gave it on the hypothesis of the materiality of heat, is ex absurdo. It is as follows. Suppose a heat-engine A to be capable of giving more work from a given amount of heat than is a reversible engine B, the temperatures of source and condenser being the same for each. Use the two as a compound engine, A working direct and B reversed. By hypothesis B requires to be furnished with part only of the work given by A to be able to restore to the source the heat abstracted by A, and thus at every complete stroke of the compound engine the source has its heat restored to it, while a certain amount of external work has been done. This would be the Perpetual Motion (q.v.).

5. The Basis of the Second Law of Thermodynamics.—Carnot's reasoning, just given, is based on the hypothesis that heat (or caloric) is indestructible, and that (under certain conditions) it does work in being let down from a higher to a lower temperature, just as does water when falling to a lower level. It is clear from several expressions in his work that Carnot was not at all satisfied with this view, even in 1824, and we have seen that he soon after wards reached the true theory. But it is also clear that such an assumption somewhat simplifies the reasoning, for in his hypothetical heat-engine all the heat which leaves the boiler goes to the condenser, and vice versa in the reversed working. The precise point of Carnot's investigation where the supposed indestructibility of heat introduces error is when, after virtually saying compress from Q to a state Q determined by the condition that the heat given out shall be exactly equal to that taken in during the expansion from P to P, he assumes that, on farther com pressing adiabatically to the original volume, the point P will be reached and the cycle completed. J. Thomson, in 1849, rectified this by putting it in the true form: compress from Q to a state Q, such that subsequent adiabatic compression will ultimately lead to the state P.

We have now to consider that, if an engine (whether simple or compound) does work at all by means of heat, less heat necessarily reaches the condenser than left the boiler. Hence, if there be two engines A and B as before, and the joint system be worked in such a way that B constantly restores to the source the heat taken from it by A, we can account for the excess of work done by A over that spent on B solely by supposing that B takes more heat from the condenser than A gives to it. Such a compound engine would transform into work heat taken solely from the condenser. And the work so obtained might be employed on B, so as to make it convey heat to the source while farther cooling the condenser.

Clausius, in 1850, sought to complete the proof by the simple statement that "this contradicts the usual behaviour of heat, which always tends to pass from warmer bodies to colder." Some years later he employed the axiom, "it is impossible for a self-acting machine, unaided by any external agency, to convey heat from one body to another at a higher temperature." W. Thomson, in 1851, employed the axiom, "it is impossible, by means of inanimate material agency, to derive mechanical effect from any portion of matter by cooling it below the temperature of the coldest of the surrounding objects." But he was careful to supplement this by further statements of an extremely guarded character. And rightly so, for Clerk-Maxwell has pointed out that such axioms are, as it were, only accidentally correct, and that the true basis of the second law of thermodynamics lies in the extreme smallness and enormous number of the particles of matter, and in consequence the steadiness of their average behaviour. Had we the means of dealing with the particles individually, we could develop on the large scale what takes place continually on a very minute scale in every mass of gas,—the occasional, but ephemeral, aggregation of warmer particles in one small region and of colder in another.

6. The Laws of Thermodynamics.—I. When equal quantities of mechanical effect are produced by any means whatever from purely thermal sources, or lost in purely thermal effects, equal quantities of heat are put out of existence, or are generated. [To this we may add, after Joule, that in the latitude of Manchester 772 foot-pounds of work are capable of raising the temperature of a pound of water from 50°F. to 51°F. This corresponds to 1390 foot-pounds per centigrade degree, and in metrical units to 425 kilogramme-metres per calorie (see Heat).]

II. If an engine be such that, when it is worked backwards, the physical and mechanical agencies in every part of its motions are all reversed, it produces as much mechanical effect as can be produced by any thermodynamic engine, with the same temperatures of source and refrigerator, from a given quantity of heat.

7. Absolute Temperature.—We have seen that the fraction of the heat supplied to it which a reversible engine can convert into work depends only on the temperatures of the boiler and of the condenser. On this result of Carnot's Sir W. Thomson based his absolute definition of temperature. It is clear that a certain freedom of choice is left, and Thomson endeavoured to preserve as close an agreement as possible between the new scale and that of the air thermometer. Thus the definition ultimately fixed on, after exhaustive experiments, runs:—"The temperatures of two bodies are proportional to the quantities of heat respectively taken in and given out in localities at one temperature and at the other respectively, by a material system subjected to a complete cycle of perfectly reversible thermodynamic operations, and not allowed to part with or take in heat at any other temperature; or, the absolute values of two temperatures are to one another in the proportion of the heat taken in to the heat rejected in a perfect thermodynamic engine, working with a source and refrigerator at the higher and lower of the temperatures respectively."[2] If we now refer again to fig. 1, we see that, and being the absolute temperatures corresponding to PP′ and QQ′, and H, H′ the amounts of heat taken in during the operation PP′ and given out during the operation Q′Q respectively, we have

whatever be the values of and . Also, if heat be measured in terms of work, we have

Thus with a reversible engine working between temperatures and the fraction of the heat supplied which is converted into work is

It is now evident that we can construct Watt's diagram in such a way that the lines of equal temperature and the adiabatics may together intercept a series of equal areas.

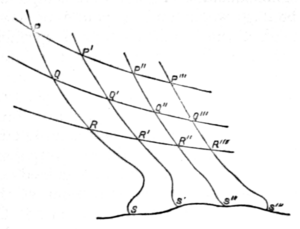

Fig. 2.

Thus let PP′ (fig. 2) be the isothermal , and on it so take points P′, P′′, P′′′, &c., that, as the working substance passes from P to P′, P to P′′, &c., units of heat (the unit being of any assigned value) shall in each case be taken in. Let QQ′, RR′, &c., be other isothermals, so drawn that the successive areas PQ′, QR′, &c., between any two selected adiabatics, may be equal. Then, as it is clear that all the successive areas between each one pair of isothermals are equal (each representing the area ), it follows that all the quadrilateral areas in the figure are equal.

It is now clear that the area included between PP′ and the two adiabatics PQR, P′Q′R′ is essentially finite, being numerically equal to . Thus the temperature for each isothermal is represented by the corresponding area. This is indicated in the cut by the introduction of an arbitrary line SS′, supposed to be the isothermal of absolute zero. The lower parts of the adiabatics also are unknown, so that we may draw them as we please, subject to the condition that the entire areas PS′, P′S′′, P′′S′′′, &c., shall all be equal. To find, on the absolute scale, the numerical values of two definite temperatures, such as the usually employed freezing and boiling points of water, we must therefore find their ratio (that of the heat taken and the heat rejected by a reversible engine working between these temperatures), and assign the number of degrees in the interval.

Thomson and Joule experimentally showed that this ratio is about 1.365. Hence, if we assume (as in the centigrade scale) 100 degrees as the range, the temperatures in question are 274 and 374 nearly. A full discussion of this most important matter will be found under Heat.

8. Entropy.—Just as the lines PP′, QQ′, &c., are characterized by constant temperature along each, so we figure to ourselves a quantity which is characteristic of each adiabatic line,—being constant along it. The equation of last section at once points out such a quantity. If we write for its value along PQ, for P′Q′, we may define thus

From the statements as to the equality of the areas in fig. 2 the reader will see at once that the area bounded by is . We are concerned only with the changes of , not with its actual magnitude, so that any one adiabatic may be chosen as that for which .

9. The Dissipation of Energy.—In the before-cited article Energy (vol. viii. p. 210) this part of the subject has already been treated. Since that article was written Sir William Thomson has introduced the term thermodynamic motivity to signify "the possession the waste of which is called dissipation." We speak of a distribution of heat in a body or system of bodies as having motivity, and we may regard it from without or from within the system.

In the first case it expresses the amount of work which can be obtained by means of perfect engines employed to reduce the whole system to some definite temperature, that, say, of the surrounding medium. In the second case the system is regarded as self-contained, its hotter parts acting as sources, and its colder parts as condensers for the perfect engine.

As an instance of internal motivity we may take the case of a system consisting of two equal portions of the same substance at different temperatures, say a pound of boiling water and a pound of ice-cold water. If we neglect the (small) change of specific heat with temperature, it is found that, when the internal motivity of the system is exhausted, the temperature is about 46°C., being the centigrade temperature corresponding to the geometrical mean of the original absolute temperatures of the parts. Had the parts been simply mixed so as to dissipate the internal motivity, the resulting temperature would have been 50°C. Thus the work gained (i.e., the original internal motivity) is the equivalent of the heat which would raise two pounds of water from 46°C. to 50°C.

As an instance of motivity regarded from without we may take the simple case of the working substance in §2, on the hypothesis that there is an assigned lower temperature limit. As there is no supply of heat, it is clear that the maximum of work will be obtained by allowing the substance to expand adiabatically till its temperature sinks to the assigned limit.

Thus if P (fig. 3) be its given position on Watt's diagram, PQ the adiabatic through P, and PQ the isothermal of the lower temperature limit, Q is determinate, and the motivity is the area PQNM.

Fig. 3.

If, again, we wish to find the motivity when the initial and final states P and P' are given, with the condition that the temperature is not to fall below that of the state P', the problem is reduced to finding the course PP' for which the area PP'M'M is greatest. As no heat is supplied, the course cannot rise above the adiabatic PQ, and by hypothesis it cannot fall below the isothermal P'Q,—hence it must be the broken line PQP'. Thus, under the circumstances stated, the motivity is represented by the area MPQP'M'. If any other lawful course, such as PP', be taken, there is an unnecessary waste of motivity represented by the area PQP'.

10. Elementary Thermodynamic Relations.—From what precedes it is clear that, when the state of unit mass of the working substance is given by a point in the diagram, an isothermal and an adiabatic can be drawn through that point, and thus and are determinate for each particular substance when and are given. Thus any two of the four quantities may be regarded as functions of the other two, chosen as independent variables. The change of energy from one state to another can, of course, be expressed as in §9, above. Thus, putting E for the energy, we have at once

. . . . .(1)

if and be chosen as independent variables, and if heat be measured, as above, in units of work. This equation expresses, in symbols, the two laws of thermodynamics. For it states that the gain of energy is the excess of the heat supplied over the work done, which is an expression of the first law. And it expresses the heat supplied as the product of the absolute temperature by the gain of entropy, which is a statement of the second law in terms of Thomson's mode of measuring absolute temperature.

But we now have two equations in partial differential coefficients:—

From these we have two expressions for the value of

Equating them, we are led to the thermodynamic relation

the differential coefficients being again partial.

This expresses a property of all "working substances," defined as in §1. To state it in words, let us multiply and divide the right hand side by , and it then reads:—

The rate at which the temperature falls off per unit increase of volume in adiabatic expansion is equal to the rate at which the pressure increases per dynamical unit of heat supplied at constant volume, multiplied by the absolute temperature.

To obtain a similar result with and as independent variables, we have only to subtract from both sides of (1) the complete differential so that

Proceeding exactly as before, we find

In words this result runs (when both sides are multiplied by ):—

The rate of increase of pressure with temperature at constant volume, multiplied by the absolute temperature, is equal to the rate at which heat must be supplied per unit increase of volume to keep the temperature constant.

Very slight variations of the process just given obtain the following varieties of expression:—

which are to be interpreted as above.

11. Increase of Total Energy under various Conditions.—The expression (1) of §10 may be put in various forms, each convenient for some special purpose. We give one example, as sufficiently showing the processes employed. Thus, suppose we wish to find how the energy of the working substance varies with its volume when the temperature is kept constant, we must express dE in terms of dv and dt. Thus

But we have, by §10, under present conditions

Hence

a result assumed in a previous article (Radiation vol. xx. p. 217).

If the working substance have the property (that of the so-called "ideal" perfect gas)

we see that, for it,

The energy of (unit mass of) such a substance thus depends upon its temperature alone.

12. Specific Heat of a Fluid.—Specific heat in its most general acceptation is the heat required, under some given condition, to raise the temperature of unit mass by one degree. Thus it is the heat taken in while the working substance passes, by some assigned path, from one isothermal t to another t + 1; and this may, of course, have as many values as there are possible paths. Usually, however, but two of these paths are spoken of, and these are taken parallel respectively to the coordinate axes in Watt's diagram, so that we speak of the specific heat at constant volume or at constant pressure. In what follows these will be denoted by c and k respectively.

Take v and p for the independent variables, as in the diagram, and let be the specific heat corresponding to the condition

Then

while

And

Thus

This expression vanishes if and vary together, i.e., in adiabatic expansion, and becomes infinite if and vary together, i.e., in isothermal expansion; as might easily have been foreseen. Otherwise it has a finite value. It is usual, however, to choose and as independent variables, while we deal analytically (as distinguished from diagrammatically) with the subject. From this point of view we have

THERMODYNAMICS 287 But the last term on the right is, by definition, cdt ; so that dt f# + |^0. dt dv with the condition Thus K-C= -i- dv dt I dv which is a perfectly general expression. As the most important case, let /represent the pressure, then we see, by 10, that d<f> dp dv^ dt and the formula becomes 13. Properties of an Ideal Substance which follows the Laws of Boyle and Charles. Closely approximate ideas of the thermal behaviour of a gas such as air, at ordinary temperatures and pres sures, may be obtained by assuming the relation which expresses the laws of Boyle and Charles. formula of last section, we have at once Thus, by the a relation given originally by Carnot. Hence, in such a substance, dt , T d(f> = c + (K- t dv In terms of volume and pressure, this is tf> - = c log^/R + k log v , the equation of the adiabatics on Watt s diagram. This is (for $ constant) the relation between p and v in the pro pagation of sound. It follows from the theory of wave-motion (HYDROMECHANICS) that the speed of sound is &~T7 where t is the temperature of the undisturbed air. This expres sion gives, by comparison with the observed speed of sound, a very accurate determination of the ratio kjc in terms of R. The value of R is easily obtained by experiment, and we have just seen that it is equal to k - c ; so that k and c can be found for air with great accuracy by this process, a most remarkable instance of the indirect measurement of a quantity (c) whose direct determination presents very formidable difficulties. 14. Effect of Pressure on the Melting or Boiling Point of a Sub stance. By the second of the thermodynamic relations in 10, above, we have so that dt dv But, if the fraction e of the working substance be in one molecular state (say liquid) in which V is the volume of unit mass, while the remainder 1 - e is in a state (solid) where Yj is the volume of unit mass, we have obviously p-eVo+a-dVj. Let L be the latent heat of the liquid, then td<j> L /<ty V dv ) ~ t Also, as in a mixture of the same substance in two different states, the pressure remains the same while the volume changes at con stant temperature, we have dp/dv=0, so that finally which shows how the temperature is altered by a small change of pressure. In the case of ice and water, V x is greater than V , so the temperature of the freezing-point is lowered by increase of pressure. When the proper numerical values of V , V a , and L are introduced, it is found that the freezing point is lowered by about 0074 C. for each additional atmosphere. When water and steam are in equilibrium, we have V much greater than V 1} so that the boiling-point (as is well known) is raised by pressure. The same happens, and for the same reason, with the melting point, in the case of bodies which expand in the act of melting, such as beeswax, paraffin, cast-iron, and lava. Such bodies may therefore be kept solid by sufficient pressure, even at temperatures far above their ordinary melting points. This is, in a slightly altered form, the reasoning of James Thomson, alluded to above as one of the first striking applications of Carnot s methods made after his work was recalled to notice. 15. Effect of Pressure on Maximum Density Point of Water. One of the most singular properties of water at atmospheric pres sure is that it has its maximum density at 4 C. Another, first pointed out by Canton in 1764, is that its compressibility (per atmosphere) is greater at low than at ordinary temperatures, being, according to his measurements, 000,049 at 34 F., and only 000, 044 at 64 F. It is easy to see (though it appears to have been first pointed out by Puschl in 1875) that the second jof these properties involves the lowering of the maximum density point by increase of pressure. To calculate the numerical amount of this effect, note that the expansibility, like all other thermal properties, may be expressed as a function of any two of the quantities p, v, t, < ; say in the present case p and t. Then we have for the expan sibility dv Also the compressibility may be expressed as 1 (dv f d . t= ( -=- = - (-,- }logv . vdpj dpj The relation between small simultaneous increments of pressure and temperature, which are such as to leave the expansibility unchanged, is thus Now the expansibility is zero at the maximum density point, for which therefore this equation holds. But the equations above so that The volume of water at low temperatures under atmospheric pres sure varies approximately as 144,000 ~rff) = 79 nno near ly> and from Canton s experi mental result above stated we gather that (roughly at least) Thus we have ( 1 = _ 0-000,005%^= -0-000,000,3 ; dt J oO from which the formula gives - 02 C. nearly for the change of the maximum density point due to one additional atmosphere. Recent investigations, carried out by direct as well as by indirect methods, seem to agree in showing that the true value is somewhat less than this, viz., about -0 018 C. ; so that water has its maximum density at C. when subjected to about 223 atmo spheres. Thus, taking account of the result of 14 above, we find that the maximum density point coincides with the freezing point at - 2" 8 C. under an additional pressure of about 377 atmospheres, or (say) 2 5 tons weight per square inch. 16. Motivity and Entropy, Dissipation of Energy. The motivity of the quantity H of heat, in a body at temperature t, is where t is the lowest available temperature. The entropy is expressed simply as TT // Xi/w being independent of any limit of temperature. If the heat pass, by conduction, to a body of temperature tf (less than t, but greater than t ), the change of motivity (i.e., the dis sipation of energy) is which is, of course loss; while the corresponding change of entropy is the gain Hf^-i The numerical values of these quantities differ by the factor t , so that, if we could have a condenser at absolute zero, there could be no dissipation of energy. But we see that Clausius s statement that the entropy of the universe tends to a maximum is practically merely another way of expressing Thomson s earlier theory of the dissipation of energy. When heat is exchanged among a number of bodies, part of it being transformed by heat-engines into work, the work obtainable (i.e., the motivity) is

The work obtained, however, is simply

Thus the waste, or amount needlessly dissipated, is

This must be essentially a positive quantity, except in the case when perfect engines have been employed in all the operations. In that case (unless indeed the unattainable condition t0=0 were fulfilled)

which is the general expression of reversibility.

17.Works on the Subject.—Carnot’s work has, as we have seen, been reprinted. The scattered papers of Rankine, Thomson, and Clausius have also been issued in collected forms. So have the experimental papers of Joule. The special treatises on Thermodynamics are very numerous; but that of Clerk-Maxwell (Theory of Heat), though in some respects rather formidable to a beginner, is as yet far superior to any of its rivals.(P. G. T.)

- ↑ The author, N-L-Sadi Carnot (1796-1832), was the second son of Napoleon's celebrated minister of war, himself a mathematician of real note even among the wonderful galaxy of which France could then boast. The delicate constitution of Sadi was attributed to the agitated circumstances of the time of his birth, which led to the proscription and temporary exile of his parents. He was admitted in 1812 to the Nicole Polytechnique, where he was a fellow-student of the famous Chasles. Late in 1814 he left the school with a commission in the Engineers, and with prospects of rapid advancement in his profession. But Waterloo and the Restoration led to a second and final proscription of his father; and, though Sadi was not himself cashiered, he was purposely told off for the merest drudgeries of his service; il fut envoye successivemeut dans plusieurs places fortes pour y faire son metier d ingenieur, compter des briques, reparer des pans de murailles, et lever des plans destines a's eufouir dans les cartons," as we learn from a biographical notice written by his younger brother. Disgusted with an employment which afforded him neither leisure for original work nor opportunities for acquiring scientific instruction, he presented himself in 1819 at the examination for admission to the staff-corps (etat-major), and obtained a lieutenancy. He now devoted himself with astonishing ardour to mathematics, chemistry, natural history, technology, and even political economy. He was an enthusiast in music and other fine arts; and he habitually practised as an amusement, while deeply studying in theory, all sorts of athletic sports, including swimming and fencing. He became captain in the engineers in 1827, but left the service altogether in the following year. His naturally feeble constitution, farther weakened by excessive devotion to study, broke down finally in 1832. A relapse of scarlatina led to brain fever, from which he had but partially recovered when he fell a victim to cholera. Thus died, at the early age of thirty-six, one of the most profound and original thinkers who have ever devoted themselves to science. The work named above was the only one he published. Though of itself sufficient to put him in the very fore most rank, it contains only a fragment of Sadi Carnot's discoveries. Fortunately his manuscripts have been preserved, and extracts from them have been appended by his brother to a reprint (1878) of the Puissance Motrice. These show that he had not only realized for himself the true nature of heat, but had noted down for trial many of the best modern methods of finding its mechanical equivalent, such as those of Joule with the perforated piston and with the internal friction of water and mercury. W. Thomson's experiment with a current of gas forced through a porous plug is also given. One sentence of extract, however, must suffice, and it is astonishing to think that it was written over sixty years ago. "On peut done poser en these generale que la puissance motrice est en quantite invariable dans la nature, qu elle n est jamais, a proprement parler, ni produite, ni dttruite. A la verite, elle change de forme, c est-a-dire qu elle produit tantot un genre de mouvement, tantot un autre; mais elle n est jamais aneantie."

- ↑ Trans. R.S.E., May 1854.