The American Magazine (1906-1956)/Volume 64/Following the Color Line

THE AMERICAN MAGAZINE

FOLLOWING THE COLOR LINE

BY RAY STANNARD BAKER

ILLUSTRATED WITH PHOTOGRAPHS SPECIALLY TAKEN BY A. B. PHELAN

THE CLASH OF THE RACES IN A SOUTHERN CITY

I ARRIVED in Atlanta, Georgia, on the first day of last November. The riot, which I described a month ago, had taken place about six weeks before, and the city was still in the throes of self-examination and reconstruction. Public attention had been peculiarly riveted upon the facts of race relationships not only in Atlanta but throughout the South, and all manner of remedies and solutions were under sharp discussion. If I had traveled the country over, I could not have found a more favorable time or place to begin following the color line.

I had naturally expected to find people talking about the Negro, but I was not at all prepared to find the subject occupying such an overshadowing place in Southern affairs. In the North we have nothing at all like it; no question which so touches every act of life, in which everyone, white or black, is so profoundly interested. In the North we are mildly concerned in many things; the South is overwhelmingly concerned in this one thing.

And this is not surprising, for the Negro in the South is both the labor problem and the servant question; he is pre-eminently the political issue, and his place, socially, is of daily and hourly discussion. A Negro minister I met told me a story of a boy who went as a sort of butler's assistant in the home of a prominent family in Atlanta. His people were naturally curious about what went on in the white man's house. One day they asked him:

"What do they talk about when they's eating?"

The boy thought a moment; then he said:

"Mostly they discusses us culled folks."

What Negroes Talk About

The same consuming interest exists among the Negroes. A very large part of their conversation deals with the race question. I had been at the Piedmont Hotel only a day or two when my Negro waiter began to take especially good care of me. He flecked off imaginary crumbs and gave me unnecessary spoons. Finally, when no one was at hand, he leaned over and said:

"I understand you're down here to study the Negro problem."

"Yes," I said, a good deal surprised. "How did you know it?"

"Well, sir," he replied, "we've got ways of knowing things."

He told me that the Negroes had been much disturbed ever since the riot and that he knew many of them who wanted to go North. "The South," he said, "is getting to be too dangerous for colored people." His language and pronunciation were surprisingly good. I found that he was a college student, and that he expected to study for the ministry.

"Do you talk much about these things among yourselves?" I asked:

"We don't talk about much else," he said. "It's sort of life and death with us."

Another curious thing happened not long afterwards. I was lunching with several fine Southern men, and they talked, as usual, with the greatest freedom in the full hearing of the Negro waiters. Somehow, I could not help watching to see if the Negroes took any notice of what was said. I wondered if they were sensitive. Finally, I put the question to one of my friends:

"Oh," he said, "we never mind them; they don't care."

One of the waiters instantly spoke up:

"No, don't mind me; I'm only a block of wood."

First Views of the Negroes

I set out from the hotel on the morning of my arrival to trace the color line as it appeared, outwardly, in the life of such a town.

Atlanta is a singularly attractive place, as bright and new as any Western city. Sherman left it in ashes at the close of the war; the old buildings and narrow streets were swept away and a new city was built, which is now growing in a manner not short of astonishing. It has. 115,000 to 125,000 inhabitants, about a third of whom are Negroes, living in more or less detached quarters in various parts of the city, and giving an individuality to the life interesting enough to the unfamiliar Northerner. A great many of them are always on the streets, far better dressed and better-appearing than I had expected to see—having in mind, perhaps, the tattered country specimens of the penny postal cards. Crowds of Negroes were at work mending the pavement, for the Italian and Slav have not yet appeared in Atlanta, nor indeed to any extent anywhere in the South, I stopped to watch a group of them. A good deal of conversation was going on, here and there a Negro would laugh with great good humor, and several times I heard a snatch of a song: much jollier workers than our grim foreigners, but evidently not working so hard. A fire had been built to heat some of the tools, and a black circle of Negroes were gathered around it like flies around a drop of molasses and they were all talking while they warmed their shins—evidently having plenty of leisure.

As I continued down the street, I found that all the drivers of wagons and cabs were Negroes; I saw Negro newsboys, Negro porters, Negro barbers, and it being a bright day, many of them were in the street—on the sunny side.

I commented that evening to some Southern people I met, on the impression, almost of jollity, given by the Negro workers I had seen. One of the older ladies made what seemed to me a very significant remark:

"They don't sing as they used to," she said. "You should have known the old darkeys of the plantation. Every year, it seems to me, they have been losing more and more of their care-free good humor. I sometimes feel that I don't know them any more. Since the riot they have grown so glum and serious that I'm free to say I'm scared of them!"

One of my early errands that morning led me into several of the great new office buildings, which bear testimony to the extraordinary progress of the city. And here I found one of the first evidences of the color line for which I was looking. In both buildings, I found a separate elevator for colored people. In one building, signs were placed reading:

For Whites Only.

In another I copied this sign:

This Car for Colored Passengers, Freight, Express, and Packages.

Curiously enough, as giving an interesting point of view, an intelligent Negro with whom I was talking a few days later asked me:

"Have you seen the elevator sign in the Century Building?"

I said I had.

"How would you like to be classed with 'freight, express and packages'?"

I found that no Negro ever went into an elevator devoted to white people, but that white people often rode in cars set apart for colored people. In some cases the car for Negroes is operated by a white man, and in other cases, all the elevators in a building are operated by colored men. This is one of the curious points of industrial contact in the South which somewhat surprise the Northern visitor. In the North a white workman, though having no especial prejudice against the Negro, will often refuse to work with him; in the South, while the social prejudice is strong, Negroes and whites work together side by side in many kinds of employment.

I had an illustration in point not long afterward. Passing the post office, I saw several mail-carriers coming out, some white, some black, talking and laughing, with no evidence, at first, of the existence of any color line. Interested to see what the real condition was, I went in and made inquiries. A most interesting and significant condition developed. I found that the postmaster, who is a wise man, sent Negro carriers up Peachtree and other fashionable streets, occupied by wealthy white people, while white carriers were assigned to beats in the mill districts and other parts of town inhabited by the poorer classes of white people.

"You see," said my informant, "the Peachtree people know how to treat Negroes. They really prefer a Negro carrier to a white one; it's natural for them to have a Negro doing such service. But if we sent Negro carriers down into the mill district they might get their heads knocked off."

Then he made a philosophical observation:

"If we had only the best class of white folks down here and the industrious Negroes, there wouldn't be any trouble."

The Jim Crow Car

One of the points in which I was especially interested was the "Jim Crow" regulations, that is, the system of separation of the races in street cars and railroad trains. Next to the question of Negro suffrage, I think the people of the North have heard more of the Jim Crow legislation than of anything else connected with the Negro problem. I have seen, so far, no better place than the street car for observing the points of human contact between the races, betraying as it does every shade of feeling upon the part of both. In almost no other relationship do the races come together, physically, on anything like a common footing. In their homes and in ordinary employment, they meet as master and servant; but in the street cars they touch as free citizens each paying for the right to ride, the white not in a place of command, the Negro without an obligation of servitude. Street-car relationships are, therefore, symbolic of the new conditions. A few years ago, the Negro came and went in the street cars in most cities and sat where he pleased, but gradually Jim Crow laws or local regulations were passed forcing him into certain seats at the back of the car.

Since I have been here in Atlanta, the newspapers report two significant new developments in the policy of separation. In Savannah, Jim Crow ordinances have gone into effect for the first time, causing violent protestations on the part of the Negroes and a refusal by many of them to use the cars at all. Montgomery, Ala., about the same time, went one step further and demanded, not separate seats in the same car, but entirely separate cars for whites and blacks. There could be no better visible evidence of the increasing separation of the races, and of the determination of the white man to make the Negro "keep his place," than the evolution of the Jim Crow regulations.

I was curious to see how the system worked out in Atlanta. Over the door of each car, I found this sign:

White People Will Seat from Front of Car toward the Back, and Colored People from Rear Toward Front.

Sure enough, I found the white people in front and the Negroes behind. As the sign indicates, there is no definite line of division between the white seats and the black seats, as in many other Southern cities. This very absence of a clear demarcation is significant of many relationships in the South. The color line is drawnn but neither race knows just where it is. Indeed, it can hardly be definitely drawn in many relationships, because it is constantly changing. This uncertainty is a fertile source of friction and bitterness. The very first time I was on a car in Atlanta, I saw the conductor—all conductors are white— ask a Negro woman to get up and take a seat further back in order to make a place for a white man. I traveled a good deal, but I never saw a white person asked to vacate a back seat to make place for a Negro. I saw cars filled with white people, both front seats and back, and many Negroes standing.

At one time, when I was on a car the conductor shouted: "Here, you nigger, get back there," which the Negro, who had taken a seat too far forward, proceeded hastily to do. Of course, I am talking here of conditions as they are in Atlanta. I may find different circumstances in other cities, which I hope to develop when the time comes.

No other one point of race contact is so much and so bitterly discussed among the Negroes as the Jim Crow car. I don't know how many Negroes replied to my question: "What is the chief cause of friction down here?" with a complaint of their treatment on street cars and in railroad trains.

Why the Negro Objects to the Jim Crow Car

A Professor and some students of Gammon Theological Seminary

leading Negroes in Atlanta, "exactly as the white man does, but we don't get first-class service. We don't know when we may be dislodged from our seats to make place for a white man who has paid no more than we have. I say it isn't fair."

In answer to this complaint, the white man says: "The Negro is inferior, he must be made to keep his place. Give him a chance and he assumes social equality, and that will lead to an effort at intermarriage and amalgamation of the races. The Anglo-Saxon will never stand for that."

One of the first complaints made by the Negroes after the riot, as I showed last month, was of rough and unfair treatment on the street cars.

The committee admitted that the Negroes were not always well treated on the cars, and promised to improve conditions. Charles T. Hopkins, a leader in the Civic League and one of the prominent lawyers of the city, told me that he believed the Negroes should be given their definite seats in every car; he said that he personally made it a practice to stand up rather than to take any one of the four back seats, which he considered as belonging to the Negroes. Two other leading men, on a different occasion, told me the same thing. It is, however, a rare practice.

One result of the friction over the Jim Crow regulations is that many Negroes ride on the cars as little as possible. One prominent Negro I met said he never entered a car, and that he had many friends who pursued the same policy; he said that Negro street car excursions, familiar a few years ago, had entirely ceased. It is significant of the feeling that one of the features of the Atlanta riot was an attack on the street cars in which all Negroes were driven out of their seats. One Negro woman was pushed through an open window, and, after falling to the pavement, she was dragged by the leg across the sidewalk and thrown through a shop window. In another case when the mob stopped a car the motorman, instead of protecting his passengers, went inside and beat down a Negro with his brass control-lever.

Story of an Encounter on a Street Car

I heard innumerable stories from both white people and Negroes of encounters in the street cars. Dr. W. F. Penn, one of the foremost Negro physicians of the city, himself partly white, a graduate of Yale College, told me of one occasion in which he entered a car and found there Mrs. Crogman, wife of the colored president of Clark University. Mrs. Crogman is a mulatto so light of complexion as to be practically undistinguishable from white people. Dr. Penn, who knew her well, sat down beside her and began talking. A white man who occupied a seat in front with his wife turned and said:

"Here, you nigger, get out of that seat. What do you mean by sitting down with a while woman?"

Dr. Penn replied somewhat angrily:

"It's come to a pretty pass when a colored man cannot sit with a woman of his own race in his own part of the car."

The white man turned to his wife and said:

"Here, take these bundles. I'm going to thrash that nigger."

In half a minute the car was in an uproar,

Types of the respectable working-class Negro

WHERE THE MILL HANDS (WHITE) LIVE

Showing that there is no great difference

the two men struggling. Fortunately the conductor and motorman were quickly at hand, and Dr. Penn slipped off the car.

Conditions on the railroad trains, while not resulting so often in personal encounters, are also the cause of constant irritation. When I came South, I took particular pains to observe the arrangement on the trains. In some cases Negroes are given entire cars at the front of the train, at other times they occupy the rear end of a combination coach and baggage car, which is used in the North as a smoking compartment. The complaint here is that, while the Negro is required to pay first-class fare, he is provided with second-class accommodations. Well-to-do Negroes who can afford to travel, also complain that they are not permitted to engage sleeping-car berths. Booker T. Washington usually takes a compartment where he is entirely cut off from the white passengers. Some other Negroes do the same thing, although they are often refused even this expensive privilege. Railroad officials with whom I talked, and it is important to hear what they say, said that it was not only a question of public opinion—which was absolutely opposed to any intermingling of the races in the cars—but that Negro travel m most places was small compared with white travel, that the ordinary Negro was unclean and careless, and that it was impractical to furnish them the same accommodations, even though it did come hard on a few educated Negroes. They said that when there was a delegation of Negroes, enough to fill an entire sleeping car, they could always get accommodations. All of which gives a glimpse of the enormous difficulties accompanying the separation of the races in the South.

Another interesting point significant of tendencies came early to my attention. They have just finished at Atlanta one of the finest railroad stations in this country. The ordinary depot in the South has two waiting rooms of about the same size, one for whites and one for Negroes. But when this new station was built the whole front was given up to white people, and the Negroes were assigned a side entrance, and a small waiting room. Prominent colored men regarded it as a new evidence of the crowding out of the Negro, the further attempt to give him unequal accommodations, to handicap him in his struggle for survival. A delegation was sent to the railroad people to protest, but to no purpose. Result, further bitterness. There are in the station two lunch rooms, one for whites, one for Negroes.

A leading colored man said to me:

"No Negro goes to the lunch room in the station who can help it. We don't like the way we have been treated."

A Negro Boycott

Of course this was an unusually intelligent colored man, and he spoke for his own sort; how far the same feeling of a race consciousness strong enough to carry out such a boycott as this—and it is exactly like the boycott of a labor union—actuates the masses of ignorant Negroes, is a question upon which I hope to get more light as I proceed. I have already heard more than one colored leader complain that Negroes do not stand together. And a white planter, whom I met in the hotel, said a significant thing along this very line:

"If once the Negroes got togther and saved their money, they'd soon own the country, but they can't do it, and they never will."

After I had begun to trace the color line I found evidences of it everywhere—literally in every department of life. In the theaters, Negroes never sit downstairs, but the galleries are black with them. Of course, white hotels and restaurants are entirety barred to Negroes, with the result that colored people have their own eating and sleeping places, most of them inexpressibly dilapidated and unclean. "Sleepers wanted" is a familiar sign in Atlanta, giving notice of places where for a few cents a Negro can find a bed or a mattress on the floor, often in a room where there are many other sleepers, sometimes both men and women in the same room crowded together in a manner both unsanitary and immoral. No good public accommodations exist for the educated or well-to-do Negro. Indeed, one cannot long remain in the South without being impressed with the extreme difficulties which beset the exceptional colored man.

In slavery time, many Negroes attended white churches and heard good preaching, and Negro children were often taught by white women. Now, a Negro is never (or very rarely) seen in a white man's church. Once since I have been in the South, I saw a very old Negro woman—some much-loved mammy, perhaps—sitting down in front near the pulpit, but that is the only exception to the rule that has come to my attention. Negroes are not wanted in white churches. Consequently, the colored people, who are nothing if not religious, have some sixty churches of their own in Atlanta. Of course, the schools are separate, and have been ever since the Civil War.

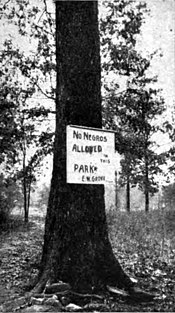

In one of the parks of Atlanta I saw this sign:

No Negroes Allowed in this Park.

Color Line in the Public Library

A story significant of the growing separation of the races is told about the public library at Atlanta, which no Negro is permitted to enter. Carnegie gave the money for building it, and when the question came up as to the support of it by the city, the inevitable color question arose. Leading Negroes asserted that their people should be allowed admittance, that they needed such an educational advantage even more than white people, and that they were to be taxed their share—even though it was small—for buying the books and maintaining the building. They did not win their point, of course, but Mr. Carnegie proposed a solution of the difficulty by offering more money to build a Negro branch library, provided the city would give the land and provide for its support. The city said to the Negroes:

"You contribute the land and we will support the library."

Influential Negroes at once arranged for buying and contributing a site for the library. Then the question of control arose. The Negroes thought that inasmuch as they gave the land and the building was to be used entirely for colored people, they should have one or two members on the board of control. This the city officials, who had charge of the matter, would not hear of; result, the Negroes would not give the land, and the branch library has never been built.

Right in this connection: while I was in Atlanta, the Art School, which In the past has often used Negro models, decided to draw the color line there, too, and no longer employ them.

Formerly Negroes and white men went to the same saloons, and drank at the same bars, as they do now, I am told, in some parts of the South. In a few instances, in Atlanta, there were Negro saloon-keepers, and many Negro bartenders. The first step toward separation was to divide the bar, the upper end for white men, the lower for Negroes. Finally, after the riot, all Negro saloon-keepers were thrown out of business, and by the new requirement no saloon can serve both white and colored men.

Consequently, going along Decatur Street, one sees the saloons designated by conspicuous signs:

"Whites Only."

"Colored Only."

And when the Negro suffers the ordinary consequences of a prolonged visit to Decatur Street, and finds himself in the city prison, he is separated there, too, from the whites. And afterwards in court, if he comes to trial, two Bibles are provided; he may take his oath on one; the other Is for the white man. When he dies he is burled in a separate cemetery.

One curious and enlightening example of the infinite ramifications of the color line was given me by Mr. Logan, secretary of the Atlanta Associated Charities, which is supported by voluntary contribution. One day, after the not, a subscriber called Mr. Logan on the telephone and said:

"Do you help Negroes in your society?"

"Why, yes, occasionally," said Mr. Logan.

"What do you do that for?"

"A Negro gets hungry and cold like anybody else," answered Mr. Logan.

"Well, you can strike my name from

The color line can be followed by means of signs in some places

your subscription list. I won't give any of my money to a society that helps Negroes."

Psychology of the South

Now, this sounds rather brutal, but behind it lies the peculiar psychology of the South. This very man who refused to contribute to the associated charities, may have fed several Negroes from his kitchen and had a number of Negro pensioners who came to him regularly for help. It was simply amazing to me, considering the bitterness of racial feeling, to see how lavish many white families are in giving fo3d, clothing and money to individual Negroes whom they know. If is said that the Southern housewife never serves hash; certainly I haven't seen so far a sign of it since I came down here. The admit "made-over dishes" of economical New England are here absent, because nothing is ever left to make over. The Negro eats it up! Even bread here is not usually baked days ahead as in the North, but made fresh for every meal—the famous, delicious (and indigestible) "hot bread" of the South. A Negro cook often supports her whole family, including a lazy husband, on what she gets daily from the white man's kitchen. In some old families the "basket habit" of the Negroes is taken for granted; in the newer ones, it is, significantly, beginning to be called stealing, showing that the old order is passing and that the Negro is being held more and more strictly to account, not as a dependent vassal, but as a moral being, who must rest upon his own responsibility.

And often a Negro of the old sort will literally bulldoze bis hereditary white protector into the loan of quarters and half dollars, which both know will never be paid back.

Mr. Brittain, superintendent of schools in Fulton County, gave me an incident in point. A big Negro with whom he was wholly unacquainted came to his office one day, and demanded—he did not ask, but demanded—a job.

"What's your name?" asked the superintendent.

"Marion Luther Brittain," was the reply.

"That sounds familiar," said Mr. Brittain—it being, indeed, his own name.

"Yas, sah. Ah'm the son of yo' ol' mammy."

In short, Marion Luther had grown up on the old plantation; it was the spirit of the hereditary vassal demanding the protection and support of the hereditary baron, and he got it, of course.

The Negro who makes his appeal on the basis of this old relationship finds no more indulgent or generous friend than the Southern white man, indulgent to the point of excusing thievery and other petty

The Hotel Vendome for colored people only

offenses, but the moment he assumes or demands any other relationship or stands up as an independent citizen, the white men—at least some white men—turn upon him with the fiercest hostility. The incident of the associated charities may now be understood. It was not necessarily cruelty to a cold or hungry Negro that inspired the demand of the irate subscriber, but the feeling that the associated charities helped Negroes and whites on the same basis, as men; that, therefore, it encouraged "social equality," and that therefore it was to be slopped.

I shall have to ask the indulgence of the reader here—and all through this series—for getting away from the main-traveled road of my narrative. Sooner or later I promise solemnly to get back again, and not without the hope that I have illuminated some obscure by-way or found a new path through a thorny hedge.

Most of the examples so far given are along the line of social contact, where, of course, the repulsion Is intense. They are the outward evidences of separation, but while highly provocative, they are not really of vital importance. Negroes and whites can go to different schools, churches and saloons, and sit in different street cars, and still live pretty comfortably. But the

Barber shop managed by A. F. Herndon, the richest Negro in Atlanta

longer I remain in the South, the more clearly I come to understand how wide and deep, in other, less easily discernible ways, the chasm between the races is becoming. It takes forms that I had never dreamed of.

The New Racial Consciousness among Negroes

One of the natural and inevitable results of the effort of the white man to set the Negro off, as a race, by himself, is to awaken in him a new consciousness—a sort of racial consciousness. It drives the Negroes together for defense and offense. Many able Negroes, some largely of white blood, cut off from all opportunity of success in the greater life of the white man, become of necessity leaders of their own people. And one of their chief efforts consists in urging Negroes to work together and to stand together. In this they are only developing the instinct of defense against the white man which has always been latent in the race. This instinct exhibits itself, as in the recent Brownsville case, in the way in which the mass of Negroes often refuse to turn over a criminal of their color to white justice; it is like the instinctive clannishness of the Highland Scotch or the peasant Irish. I don't know how many Southern people have told me in different ways of how extremely difficult it is to get at the real feeling of a Negro, to make him tell what goes on in his clubs and churches or in his innumerable societies.

A Southern woman told me of a cook who had been in her service for nineteen years. The whole family really loved the old darkey: her mistress made her a confidante, in the way of the old South, in the most intimate private and family matters, the daughters told her their love affairs; they all petted her and even submitted to many small tyrannies upon her part.

"But do you know," said my hostess, "Susie never tells us a thing about her life or her friends, and we couldn't, if we tried, make her tell what goes on in the society she belongs to."

The Negro has long been defensively secretive. Slavery made him that. In the past, the instinct was passive and defensive; but with growing education and intelligent leadership it is rapidly becoming conscious, self-directive and offensive. And right there, it seems to me, though I speak yet from limited observation, lies the great cause of the increased strain in the South.

Let me illustrate. In the People's Tabernacle in Atlanta, where thousands of Negroes meet every Sunday, I saw this sign in huge letters:

For Photographs, Go to

Auburn Photo Gallery,

Operated by Colored Men.

The old-fashioned darkey preferred to go to the white man for everything; he didn't trust his own people; the new Negro, with growing race consciousness, and feeling that the white man is against him, urges his friends to patronize Negro doctors and dentists, and to trade with Negro storekeepers. The extent to which this movement has gone was one of the most surprising things that I, as an unfamiliar Northerner, found in Atlanta. In other words, the struggle of the races is becoming more and more rapidly economic.

Story of a Negro Shoe-Store

One day, walking in Broad Street, I passed a Negro shoe-store. I did not know that there was such a thing in the country. I went in to make inquiries. It was neat, well kept and evidently prosperous. I found that it was owned by a stock company, organized and controlled wholly by Negroes; the manager was a brisk youth mulatto named Harper, a graduate of Atlanta University. I found him dictating to a Negro girl stenographer. There were two reasons, he said, why the store had been opened; one was because the promoters thought it a good business opportunity, and the other was because many Negroes of the better class felt that they did not get fair treatment at white stores. At some places—not all, he said—when a Negro woman went to buy a pair of shoes, the clerk would hand them to her without offering to help her try them on; and a Negro was always kept waiting until all the while people in the store had been served. Since the new business was opened, he said, it had attracted much of the Negro trade; all the leaders advising their people to patronize him. I was much interested to find out how this young man

The first drug store in Atlanta operated by a colored man. Moses Amos is the proprietor

looked upon the race question. His first answer struck me forcibly, for it was the universal and typical answer of the business man the world over, whether white, yellow or black:

"All I want," he said, "is to be protected and let alone, so that I can build up this business."

"What do you mean by protection?" I asked.

"Well, justice between the races. That doesn't mean social equality. We have a society of our own, and that is all we want. If we can have justice in the courts, and fair protection, we can learn to compete with the white stores and get along all right."

Such an enterprise as this indicates the new, economic separation between the races.

"Here is business," says the Negro, "which I am going to do."

Considering the fact that only a few years ago, the Negro did no business at all, and had no professional men, it is really surprising to a Northerner to see what progress he has made. One of the first lines he took up was—not unnaturally—the undertaking business. Some of the most prosperous Negroes in every Southern city are undertakers, doing work exclu-

A Negro tailor shop

Homes of some colored physicians

Dr. Butler's home Dr. Porter's home

sively, of course, for colored people. Other early enterpriser, growing naturally out of a history of personal servife, were barber- ing and tailoring. Atlanta has many small Negro tailor and clothes-cleaning shops.

Wealthiest Negro in Atlanta

The wealthiest Negro in Atlanta, A. F. Herndon, operates the largest barber shop in the city; he is the president of a Negro insurance company (of which there are four in the city) and he owns and rents some fifty dwelling houses. He is said to be worth $80,000, all made, of course, since slavery.

Another occupation developing naturally from the industrial training of davery was I ployed by white men, and they hire ,„, for their jobs both white and Negro woricmen.

Small groceries and other stores are of later appearance; I saw at least a score of them in various parts of Atlanta. For the most part they are very small, many are exceedingly dirty and ill-kept; usually much poorer than corresponding places kept by foreigners, indiscriminately called " Da- goes " down here, who are in reality mostly Russian Jews and Greeks. But there are a few Negro grocery stores in Atlanta which are highly creditable. Other busi- ness enterprises include restaurants (for Negroes), printing establishments, two newspapers and several drug-stores. In other words, the Negro is rapidly building up his own business enterprises, tending to make himself independent as a race.

The appearance of Negro drug-stores was the natural result of the increasing practice of Negro doctors and dentists. Time was when all Negroes preferred to go to white practitioners, but since educated colored doctors became common, they have taken a very large part—practically all, I am told—of the practice in Atlanta. Several of them have had degrees from Northern universities, two from Yale; and one of them, at least, has some little practice among white people. The doctors are leaders among their people. Naturally they give prescriptions to be filled by druggists of their own race; hence the growth of the drug business among Negroes everywhere in the South. The first store to be established in Atlanta occupies an old wooden building in Auburn Avenue. It is operated by Moses Amos, a mulatto, and enjoys, I understand, a high degree of prosperity. I visited it. A post-office occupies one comer of the room; and it is a familiar gathering place for colored men. Moses Amos told me his story, and I found it so interesting, and so significant of the way in which Negro business men have come up, that I am setting it down briefly here:

Rise of a Negro Druggist

"I never shall forget," he said, "my first day in the drug business. It was in 1876. I remember I was with a crowd of boys in Peachtree Street, where Dr. Huss, a Southern white man, kept a drug-store. The old doctor was sitting out in front smoking his pipe. He called one little Negro after another, and finally chose me. He said:

"'I want you to live with me, work in the store, and look after my horse. "He sent me to his house and told me to tell his wife to give me some breakfast, and I certainly delivered the first message correctly. His wife, who was a noble lady, not only fed me, but made me take a bath in a sure enough porcelain tub, the first I had ever seen. When I went back to the store, I was so regenerated that the doctor had to adjust his spectacles before he knew me. He said to me:

"'You can wash bottles, put up castor oil, salts and turpentine, sell anything you know and put the money in the drawer."

"He showed me how to work the keys of the cash drawer. 'I am going to trust you,' he said. 'Don't steal from me; if you want anything ask for it, and you can have it. And don't lie; I hate a liar. A boy who will lie will steal, too. "I remained with Dr. Huss thirteen years. He sent me to school and paid my tuition out of his own pocket; he trusted me fully, often leaving me in charge of his business for weeks at a time. When he died, I formed a partnership with Dr. Butler, Dr. Slater and others, and bought the store. Our business grew and prospered, so that within a few years we had a stock worth $3,000, and cash of $800. That made us ambitious. We bought land, built a new store, and went into debt to do it. We didn't know much about business—that's the Negro's chief trouble—and we lost trade by changing our location, so that in spite of all we could do, we failed and lost everything, though we finally paid our creditors every cent. After many trials we started again in 1896 in our present store; to-day we are doing a good business; we can get all the credit we want from wholesale houses, we employ six clerks, and pay good interest on the capital invested."

Greatest Difficulties Met by Negro Business Men

I asked him what was the greatest difficulty he had to meet. He said it was the credit system; the fact that many Negroes have not learned financial responsibility. Once, he said, he nearly stopped business on this account.

"I remember," he said, "the last time we got into trouble. We needed $400 to pay our bills. I picked out some of our best customers and gave them a heart-to-heart talk and told them what trouble we were in. They all promised to pay; but on the day set for payment, out of $1,680 which they owed us we collected just $8.25. After that experience we came down to a cash basis. We trust no one, and since then we have been doing well."

He said he thought the best opportunity for Negro development was in the South where he had his whole race behind him. He said he had once been tempted to go North looking for an opening.

"How did you make out?" I asked.

"Well, I'll tell you," he said, "when I got there I wanted a shave; I walked the streets two hours visiting barber shops, and they all turned me away with some excuse. I finally had to buy a razor and shave myself! That was just a sample. I came home disgusted and decided to fight it out down here where I understood conditions."

Of course only a comparatively few Negroes are able to get ahead in business. They must depend almost exclusively on the trade of their own race, and they must meet the highly organized competition of white men. But it is certainly significant that even a few—all I have met so far are mulattoes, some very white—are able to make progress along these unfamiliar lines. Most Southern men I met had little or no idea of the remarkable extent of this advancement among the better class of Negroes, Here is a strange thing. I don't know how many Southern men have prefaced their talks with me with words something like this:

"You can't expect to know the Negro after a short visit. You must live down here like we do. Now, I know the Negroes like a book. I was brought up with them. I know what they'll do and what they won't do. I have had Negroes in my house all my life."

But curiously enough I found that these men rarely knew anything about the better class of Negroes— those who were in business, or in independent occupations, those who owned their own homes. They did come into contact with the servant Negro, the field hand, the common laborer, who make up, of course, the great mass of the race. On the other hand, the best class of Negroes did not know the higher class of white people, and based their suspicion and hatred upon the acts of the poorer sort of whites with whom they naturally came into contact. The best elements of the two races are as far apart as though they lived in different continents; and that is one of the chief causes of the growing danger of the Southern situation. Last month I showed the striking fact that one of the first— almost instinctive—efforts at reconstruction after the Atlanta riot was to bring the best elements of both races together, so that they might, by becoming acquainted and gaining confidence in each other, allay suspicion and bring influence to bear upon the lawless elements of both white people and colored.

Many Southerners look back wistfully to the faithful, simple, ignorant, obedient, cheerful, old plantation darkey and deplore his disappearance. They want the New South, but the old darkey. That darkey is disappearing forever along with the old feudalism and the old-time exclusively agricultural life.

A New Negro is not less inevitable than a new white man and a New South. And the New Negro, as mv clever friend says, doesn't laugh as much as the old one. It is grim business he in; in, this being free, this new, fierce struggle in the open competitive field for the daily loaf Many go down to vagrancy and crime in that struggle; a few will rise. The more rapid the progress (with the trained white man setting the pace), the more frightful the mortality.

(Mr. Baker's narrative of observation of Southern life will continue next month)