Golden Fleece (magazine)/Volume 1/Issue 2/Golden Hour of Guchee

Kara Yussuf, khan of the Black Sheep Turkomans, was feasting hugely in the mountains of Kopet. The feast of the bakshi, he called it.

In the evergreen gloom of a lofty gorge thousands of campfires licked off the twilight. Around each of the campfires were men. They disposed themselves busily, sewing boots, whetting spears, picking flints from the frogs of their horses.

At each fire a brass kettle of mutton-rice stew steamed and bubbled and smelled fat and rank. The men liked that smell, and sniffed often.

Mountaineers, not subjects of the Black Sheep khan, trudged from fire to fire, peddling provisions. The Turkomans swapped knives with the mountain men and baited the red-kirtled women. The feast of the singing bakshi seemed to be in a grand good humor.

Kara Yussuf himself, flinging thrift to the winds, entertained in his goat-hair pavilion. Black-bearded, pinch-eyed, with a sword-cleft in his chin, he symbolized courage and cunning. Primed with wine he waved greetings and hallooed to the fires; but talked low in the ears of his chieftains.

In the spirit of peace and goodwill to mankind, Kara Yussuf had discarded his weapons. His war helmet was passed, full of sweetmeats. Though his sabre still hung in the sheath at his belt, it was hidden by the long jubba of rainbow silk reserved for holiday splendor.

At one of the reeking pots of p'lov, outside the regal pavilion, a man stared at the khan, fascinated. He, too, had a split beard of the same square cut, a cleft in his chin, and a squint. His hair, his eyes, in a loose way his whole aspect, resembled the face of the khan.

The resemblance stopped short in the matter of the soul; for the fellow looked dreamy and kind.

When the khan dipped his fist into his mutton-rice mess, the man aped him, though he burned his whole hand. He imitated the khan's every gesture. So engrossed he became in thus playing the king that one of his pot comrades shouted:

"Look, Uncle, our Guchee is at it again!"

The old fellow called Uncle cackled.

"Ay," he said, "Guchee fancies he looks like Kara Yussuf. But his belly's too round, I'm thinking."

"We can remedy that," said a squat, sunburned fellow, "by dividing amongst us his share of the kettle."

"Even then," cackled Uncle, "a good dog could detect him; for Guchee still would smell of the yaboos."

Guchee raised his cleft chin with a khan-like scorn:

"Cackle on, you old hen. My hour shall come. I was not born to look great for nothing."

"Thou wert born," said another, "to whack yaboos on the rump—"

His jest was cut short as if his tongue had been clipped. A warning stillness struck the encampment.

From the mouth of the nearest guarded pass came the jingle and thud of armed riding.

The Turkomans gripped their weapons and stared as Mangali, the Tatar, rode through.

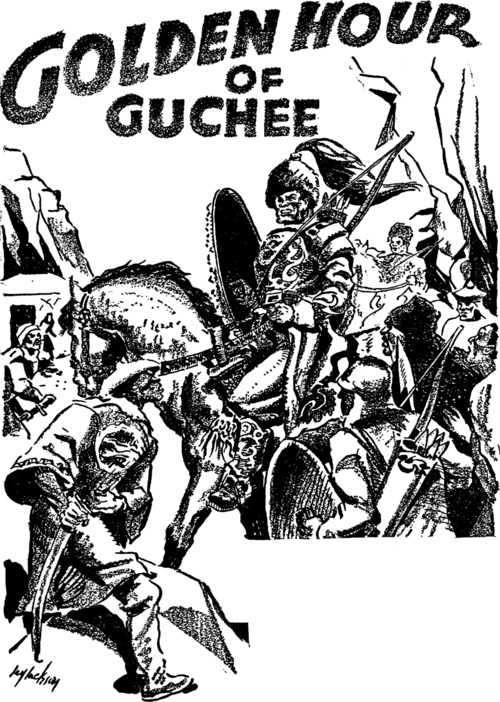

Mangali, the Tatar, great Tamerlane's friend, was equipped as beseemed the Earth-Shakers. His bridle reins dazzled with silver and sunstone; his arrow case twinkled with gold. His helmet sprouted the red horse-tail that had swept a million souls to oblivion.

None but this mighty Tatar chief could wield that appalling tulwar, double length and double width, hung by a loop of camel's hair from the horn of his brocaded saddle.

Though he was traveling through bitterly jealous lands, the Tatar led only six warriors.

Tall guards near the khan's pavilion crossed lances to halt the armed band:

"In the name of Kara Yussuf, supreme lord of the Black Sheep Turkomans, declare thy name and thy errand."

Mangali snatched a treasure bag from his belt and emptied it into the path, a shower of gleaming coins.

"Gold from the sacking of great cities," he answered scornfully. "It is Mangali, friend of Timur, rides through."

The wool-wrapped Turkomans glared stonily from their brightly dyed sheepskin bonnets. "Pass, friend of Lord Timur," they said.

When Mangali and his warriors had moved on through the pines, the guards swooped down with hungry eyes and scraped up the bloodstained fortune.

The Tatars threaded the blinding fires until they sighted the khan in his jubba.

"Ulluh yarin! God with thee!" Mangali saluted the khan.

The khan rose. "Khosh geldin! Thou art welcome, Mangali. Alight. Tarry here. Thou art even in time for the feast of the singing bakshi."

"The feast of the singing bakshi—and no women to sing?" said Mangali.

"Nay, we sing much better without them. Thou shalt stay and judge it thyself."

"Nay, Kara Yussuf, 'tis better for thee to judge the tone of thy people. I haste from the hunt back to Samarkand where Lord Timur hath need of loyal spears and shafts to drive the Jat into the sea. We shall drink a gourd of chaal with thee and thy friends, since thou art at peace with Timur."

Yussuf sent a slave for camel's milk, spicy with Kopet wines.

"At peace—with Timur," he toasted, his fiery black eyes a riddle.

Out through the lofty valley, among the odorous fires and the black felt tents of the flat-nosed Turkomans, Mangali set forth again. His hunting falcon was on his shoulder. The falcon's eyes were not more keen than the eyes of the tawny warrior. Ten thousand sheep could be shepherded in those dark bristling ravines; four or five thousand ponies.

"Ha! feast of the bakshi!" he rumbled. "They sing better, they do, without women!"

They were passing the campfire where Guchee stood, a gourd of mare's milk in his hand. Mangali checked his horse sharply.

"By the beard of my grandsire!" He turned in his saddle to stare back at the khan's pavilion.

Guchee beamed and grimaced, delighted; but the warriors about the fire laughed.

"Nay, stranger," the dried cackling Uncle explained, "Guchee is not commander of the Black Sheep Turkomans, though he knows well enough how to ape him."

"Then he must be sardar of a meeng, commander of a thousand," Mangali suggested in mock innocence.

Guchee's comrades laughed roundly. "Nay, not of a thousand; nor five hundred; nor yet a hare-chasing hundred."

"Fifty," declared Guchee, with offended pride.

"Ha ya! Fifty yaboos of the packmule train. Tell the Tatar lord how thou didst win thy scar, Guchee."

"In battle," the man answered haughtily, posing his face to the firelight so the stranger could get the effect.

"Yea, a most famous battle," drawled the leather-faced cynic. "The battle of Wood-on-Wood. When Kara Yussuf was marked by a Persian blade, this Guchee fellow banged his chin on the edge of a stump. The old wench at the well saw him do it."

A merry laughter went round the pot; even the Tatars sharing.

"Laugh, old gourds, till ye crack!" cried Guchee. "My turn shall come. He that looks like the great may be called to act for the great. Who can say what is written by Ulluh?"

"I can see 'tis a wise stick beats thy yaboos, my friend. Ulluh yarin!" said Mangali, departing. The Tatars thundered down the rock trail.

With his left hand—for the khan was left-handed—Guchee hoisted the mushk of koomiss and swigged valiantly. In lofty style he addressed the dried cynic:

"I tell thee, old jackass, thou'rt jealous. Can I help that I look like the khan? Why, when I galloped into Nisapur on my white stallion—"

"Mule!" yelled somebody.

"Fool, thou knowest my white stallion. When I galloped into Nisapur, the lord of the city with twenty dancing maidens welcomed me: saying: 'Hail, Kara Yussuf!' But I would not fare by deceit, so I convinced him he was in error."

"Twenty broken-hearted damsels," groaned someone.

"In a great hour," Guchee continued, "I could substitute for the khan. Believe it or not, ye rump-headed skeptics. It is the will of Ulluh I should look like a khan, and something important shall come of it. A holy Eeshan prophesied that."

The feast of the bakshi continued—long enough to gather the clans. Then Kara Yussuf rolled up his portable city; packed kajavaks of provisions on camels and yaboos; reviewed the largest and fiercest army of Turkomans ever mobilized by a nomad khan; galloped stealthily night by night down from the craggy Kopet range, to crack the frontiers of Timur.

In the middle of the Black Sand desert, two days from the oasis of Merv, they ran into Mangali's army.

"The old fox worked fast!" Kara Yussuf pulled his split beard. "But verily my eye is a liar, or we outnumber them two to one."

He ordered the pack train moved to the right to avoid a possible stampede. Five hundred camels, yaboos and mules, half hid in a valley of tamarisk scrub, were watched by fifty Persian slaves commanded by ten stout Turkomans, of whom Guchee was one.

Kara Yussuf set his horde in formation. Too wily to charge into a steel-tipped hail from the mighty horned bows of the Tatars, the Turkoman chief chose to wait. Lord Timur, he knew, had much need of Mangali to assist him in smashing the Jat. Mangali would not dare to dally.

Mangali accepted the challenge. His bannermen waved the advance.

"Dar u gar!" The terrible Tatar cry had paralyzed half of Asia.

Pouring death from their bristling quivers the Tatars stormed over the plain. Thousands of croaking partridges in panic-smitten swarms roared from the patchy wormwood and fought through the furling dust clouds to the sky. The crimson banners of Samarkand dartled above the low breakers of drifted sand. Plumed helmets swam along the dunes like shark fins over billows.

Confident of their overwhelming strength the Turkoman riders seized their spears and leaped to meet the whirlwind.

The crash of war was bewildering. For a time Mangali could not fight clear to see how the tide was moving. When he did cut through to the edge of the storm he saw the battle was veering against him.

Frenzied with hope of victory the Turkomans were whooping the name of their khan and driving the Tatars backward. If they broke, they were done for; a massacre. To retreat in order meant sure defeat, for the Turkomans vastly outweighed them.

Only a rally, a forward rush, could break Kara Yussuf's formation.

Turning his tawny head right and left, the veteran Tatar studied the landscape. His quick eye stopped on the baggage herd, half hid in the tamarisk bushes. Ten men in the saddle were straining their necks to observe how the battle progressed. One of these men was Guchee.

"Dar u gar!" pealed the Tatar chieftain and charged, straight into the mules and yaboos. The pack guards braced for his onslaught. A terrific melee rattled the bush, while the animals snorted and milled. Mangali was slashed through his bullshide boots, and his charger bled hard at the flanks. He fought on, through the riot, to Guchee.

A few minutes later, pursued by four, Mangali raced back to the battle; bearing aloft on the point of his spear a bearded human head. In and out among the clashing groups he lunged, braying victoriously:

"The khan is slain! The khan is slain! Behold the head of Yussuf!"

"The khan is slain!" The cry spread through the ranks of Tatars. "Behold his head! Behold his head!" The Turkomans heard, saw, hesitated. An instant was enough. The respirited Tatars raised their cry and took the aggressive madly. The Turkomans, believing themselves leaderless, flinched, wavered, broke. Their backward rout carried Kara Yussuf along, swearing mightily but unnoticed.

Mangali maneuvered his crack horse troop to force the Turkomans into their pack train. A stampede finished the battle. Unhorsed, unhelmeted, his beard floury with dust, Kara Yussuf went down with his clans.

Mangali looked up at the head on his spear. A grim smile broke through his iron features.

"By Ulluh, old fellow, 'tis a great day for thee. Thou hast achieved thy ambition!"

|

Introductory Subscription Offer For the next six Issues send $1.00 to Golden Fleece 538 So. Dearborn St. Chicago, Ill. |