Great Neapolitan Earthquake of 1857/Part II. Ch. VII

CHAPTER VII.

VILLA CARUSSO—FIRST DETERMINATIONS MADE OF WAVE-PATH'S EMERGENCE—PERTOSA—SOUNDS HEARD.

The Villa Carusso is a large proprietor's house, visible from Auletta summit, at a distance of about 1 1/2 mile in a right line; and seeing by the glass that it was a strong well-built house and nearly cardinal, I resolved to examine it. It is in general plan a parallelogram, with four towers at the angles, and a projecting sort of porch over the front and rear entrances.

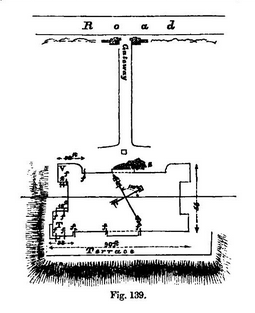

Its longest axial line is 110° E. of N. The western end is probably 400 years old, part of an ancient semi-fortified château, and the towers here are of decayed and very inferior masonry. The remainder is modern, and of tolerably good uncoursed rubble limestone masonry, the stones not above 10 to 15 inches average bed, with dressed ashlar window and door jambs, and some Italian brickwork in the arcades over the south entrance. (See Figs. 139, 140, 141, and Photog. No. 137 bis, Part I.)

The wails at the west end appear to be about 2 feet 9 inches in thickness at about 10 feet from the bases, as I found by climbing up to one of the window apertures, that shown in Fig. 141, north elevation of the tower, V, Fig. 139.

No one was to be found, and the house was tenantless, so I could only make external examination.

The only fissures are those marked , &c., in the west end, all in the ancient towers, and two fractures in the slender brickwork of the southern arcades. The towers have been thrown westward, off from the body of the building, and the fissures at the rëenterant quoins are 2 inches open at top, and run nearly from top to bottom of the walls, which are about 32 feet in height to the eaves, and the whole of the west end is out of plumb. The fissures in the south front are seen in Photog. No. 137. Their direction has been determined and limited at the quoin, by the form of the buttress built into it, for nearly half its height, and projecting at the base, as seen in ground plan, Fig. 139.

The fissures at the internal flanks of the tower, that, , (ground plan, Fig. 139), looking south, and that, , looking north, are pretty exactly sketched in Figs. 140 and 141.

These fissures slope about 30° from bottom to top towards the east, but they, like the preceding, have been rendered more nearly plumb, by the action of the buttresses and other disturbing causes acting in the interior, which I am unable to examine particularly.

Some roof-tiles have been thrown from the cave at the west end, from (Fig. 140), and are lying at , from 7 to 9 feet horizontally from the base of the wall, having fallen vertically 33 feet.

Taking the horizontal range of projection here, = 9 feet and the vertical descent from the point , = 33 feet, and assuming the velocity of projection to be 13 feet per second (which is about what it proved to be elsewhere in this neighbourhood), and solving for = the angle of elevation of the projectile which is here equal to the angle of emergence, we have,

The house was approached by an arched gateway, of rubble stone-work plastered, as seen in Photog. No. 138, looking south from the military road. This arched structure is heavily fissured, right through the crown of the arch, showing most at the south side, and in three diagonal fissures on the north side of the structure. The largest fissure is about 4 inches wide at top. The gateway is 12 feet wide and the height to the soffit is 16 feet; each pier is equivalent to about 4 feet square in horizontal section, and buttressed by the fragments of walls proceeding from them at each side. These fissures, like those of the main building, indicate a wave-path not far from E. and W., and a direction from the eastward—on the whole, about 100° west of north. The gateway fissures have had their directions mainly determined by those of the voussoirs of the arch, which is of brick; by the relative support given by the side walls as buttresses; and by the rocking of the piers as the shock passed through them; so that no inference can be drawn from them as to the angle of emergence.

In the Photog. No. 138 the rere or north front of the villa is seen, and above the projection at the central part (which corresponds to that above the "Portone" of the south front) stood, before the earthquake, a wooden sort of verandah, framed, as shown in Fig. 142, and covered by a

The shock emerging from the eastward had swept over the vertical posts towards the direction of the dotted lines , and the tiling of the roof had rent away from the rest at the line of the eave , twisting and drawing out the cross lintels from their sockets in the walls of the house at the eaves, the whole mass then falling in the direction of . The weight of the timber-work was insignificant, the chief mass was in the heavy tiling which it carried. A line drawn from the position of the centre of gravity of this (the projecting tiled roof) to the centre of gravity of the mass of rubbish upon the ground, I found made an angle of 60° with the level ground. This is, therefore, about the angle of emergence; but as the roof received a small amount of nearly horizontal motion at its centre of gravity before it began to descend, this angle is a little too small, and so it may be taken as about 62° to 64°, coinciding as thus separately determined, with the emergence as given by the tiles projected from the tower.

The villa stands upon deep clay, upon the north side of the Auletta valley, the land sloping gradually southwards with a rolling surface, and behind it still further north, the limestone mountains (apparently Apennine limestone) rise with a flowing sweep to perhaps 1,500 feet, with bedding nearly parallel to the face of the slope, and a strike in the line of the axis of the valley, or E. and W. and north of E. The calcareous breccia is probably the rock directly under the clay on which it stands, however.

By barometer I find the ground at the villa is about 110 feet above the summit of Auletta. Returning from the villa to Auletta, a good view is afforded to the N. W. and W. down the great valley, which I sketched. Castelluccio is visible, perched upon its summit in the centre, and the lower ranges of the shaggy wooded precipices upon the north flank of Monte Alburno, block up the left of the view. Contursi is just visible upon another very distant height upon the right, () and the villa Carusso is seen at the roadside at (). I proceeded on to

Pertosa.—It also stands upon the top of a mound, less lofty and steep than Auletta, and not so elongated in form. The longer axis is on the whole transverse to the course of the Tanagro, or about 30° E. of N. The steep side,

Sketch Pl. 123

|

|

From the Plain of Pœstum. |

Sketch Pl. 124

|

|

From the Plain of Pœstum. |

Sketch Pl. 145

|

|

Vincent Brooks, lith. London

|

The flanks of Monte Alburno & Castelluccio from near Auletta. |

faces towards Polla, or towards the S. and S.E., and the gentler slope towards Auletta, or N. and N.W. The steepest slope is about 55° from the vertical. The "colline" consists of solid beds of breccia of great thickness, of pebbles chiefly calcareous, but with many metamorphic hard slaty and chertose pebbles, of from 3 to 5 inches diameter, in a calcareous cement. Beneath the town these beds have a general E. and W. strike, or lengthwise to the river valley, and a dip of 30° the S. and S. E., so as to be not very far from parallel to the faces of the limestone mountain slopes, behind them to the N. and N.W.

The town was an extremely poor place, the land of the commune being less productive than that of Auletta, and chiefly the residence of working peasants. With the exception of a few new houses, low, and tolerably well built, with dressed quoin stones and jamb linings in long blocks, which have stood pretty well, though heavily fissured, all the remainder of the town was built of large oblate or ovoid calcareous boulders, of from 10 to 12 inches across, picked out of the banks and river bed below, and laid into the walls as in Figs. 143 and 144 (Coll. Roy. Soc.), without an attempt at dressing flat-beds upon them, and with thick mortar joints. The town has hence suffered fearfully and is almost completely demolished. The timbers of many of the houses after their overthrow took fire, and more than 150 corpses of the vast number buried in the ruins here, were found charred and calcined when disinterred, and in some few cases, all semblance of humanity, from the action of the quicklime produced from the calcined limestone, absolutely obliterated.

It was very painful to witness the subdued and patient endurance of the survivors, exposed to the terrible inclemency of the winter nights here, and the processions of women and children, carrying about some paltry relic, and whining litanies to the Madonna, in tones of despairing sadness. The recent visit as far as this spot of the deputation of Englishmen who came to distribute personally, the alms collected at Naples amongst our countrymen, was fresh and grateful in the memories of these poor beings, who crowded round me and struggled unwelcomely, to kiss my hands and pour "benedizioni" on all "Inglese" to such an extent, that had I not fortunately found the Padre, Vincenzio Mancini, I should have been unable to make any observation.

He was a man of much more than the average information and intelligence of his class, but conversed in no modern language except Italian, which was strongly provincial, and I found it difficult to follow him; he spoke Latin with some fluency and elegance, and I obtained from him a good deal of information.

The town has suffered most, at the east and west sides, the southern end the least. Large portions of the west side are a perfect chaos of ruin, and beyond reach of observation or analyzation, as in Photog. No. 146. The general character of the west side is seen in Photog. No. 147. The Photogs. No. 148 (Coll. Roy. Soc.) and No. 149 are views at the southern entrance near the town and towards its central part.

Those No. 150 (Coll. Roy. Soc.) and No. 151 give a tolerable notion of such portions of the town, as presented measureable elements of the direction of shock. The sketch No. 152, taken on the spot, shows a part of the west side in which the lines of street and houses were for

Photo Pl. 151

|

Sketch Pl. 159

| |

|

|

|

Vincent Brooks, lith. London.

|

||

Pertosa. |

| The Tenementa Della Madonna Campostrina |

a certain range nearly cardinal. The walls a and b, and all parallel to them, run nearly E. and W. These were in great part, more or less standing, but fissured, in sloping cracks; but the walls whose plans had been N. and S.

were universally down and in rubbish, unless something had accidentally propped them up. In the sketch No. 152, the gable wall a, had been built within about 2½ feet S. of b, a passage had probably run between them; b was kept up by flooring and other props to the northward, but a had swayed over at top to the northward, and leaned against b there, the bottom of both being buried in rubbish wherever the fracture had occurred.

The horizontal force and velocity with which a had been brought over against b, was small, as they only touched, at the top, and the space below was all hollow between, and yet a was not fractured by the coming in contact: it was about 2 ft. 3 in. thick and about 15 feet high above the rubbish. The sockets of the joists, whence they had been drawn and twisted out, were still visible on its face.

The direction of wave-path given by all this portion of the ruined town, was from E. to W. 118° to 120° 30' W. of N. The force in the N. and S. direction, therefore, which brought the wall a against b was necessarily small. In some other portions of this west side, the crooked streets brought the general position of the houses to be ordinal, nearly 40° W. on the average. The houses that were so circumstanced, were less absolutely demolished than those whose front and rear walls ran nearly cardinal or N. and S., but diagonal and crossing fissures were to be found in all directions, and huge wedge-shaped masses, as in sketch Fig. 144 were thrown out from the W. and S. W. quoins of numbers of them. From the extent to which destruction had proceeded, and the vile class of the masonry, measurements of the widths of fissures, were uncertain and the angles of fracture ill defined. From measurements and general judgment together, however, it appeared to me that the angle of emergence here must have been extremely steep, steeper than the indications at the Villa Carusso, and certainly not less than 70° with the horizon, possibly as much as 75°.

This is corroborated by the nearly universal fall of the tiled roofs and heavier floors.

In the Photogs. Nos. 149 and 150, some of the steeply-inclined fracturing is visible: some of the temporary roofs, as well as the piling up of the stones seen in No. 150, had been work done since the shock, in digging out for interment, the buried corpses.

At the east side of the town, the wave-path was more nearly E. and W., and gave a general direction of 83° 30' or 84° W. of N.

At the south portion of the town, the destruction was rather less than over the remainder. An obvious reason for the fact is afforded, now that the wave-path is obtained. The plane of the great breccia beds upon which the whole stands, is not very far from being at right angles to the direction of wave-path; hence the southern portion of the town received the blow through the greatest thickness of these beds, and thus, by the numerous and successive changes of medium, in passing from bed to bed, the force of shock here had sustained the largest mount of loss of vis vivâ.

The direction, of the longer axis of the hill on which the town was perched, also accounts for the greatest damage having been done at the E. and W. sides, and less upon the very top and more level portion of the place.

Nobody here nor at Auletta seems to have felt any second shock, occurring within a minute or two after the first; but they all speak of a second shock much less powerful than the first, but occurring about an hour after the first; testimony which appears strangely inconsistent with that universal at Naples. The Padre Mancini is positive, that there was no second shock soon (i.e. within a few minutes) after the first, of a noticeable character. He himself had escaped the first with difficulty, and only owing to the fact that he was not in bed, and so was able to rush out instantly.

As to the time of the shock, he does not know of any clocks having been stopped, inasmuch as there are none either here or at Auletta. He thinks it was at about a quarter past ten (tempo Francesi), i.e. not reckoning by Italian hours.According to his narrative, the shock was from S. to N.; but when I caused him to point with his hand to what he deemed the north, he pointed nearly to the west, and I then found, what I afterwards recognized as the usual mode of speech in the provinces, that such words as "tramontana,—dal nordo,—meridionale,—mezzogiorno," were more commonly applied to the apparent path of the sun in the heavens, from rising to setting, than with precision as signifying points of the compass. I henceforward always made the narrator point out with his hand the azimuth he intended. The testimony of the Padre therefore, which coincides with that of the postmaster down at the bottom of the valley, agrees generally with the deductions from my observations.

Padre Mancini says, the first shock was "sussultorio," and immediately became "orizontale ed oscillatorio;" and he thinks the second, of an hour after, was "vorticoso." But upon being pressed as to what he meant, he at length said "he thought the direction was not the same as the first, and changed while yet shaking; but he was not certain," adding quaintly, that his own head and those of his parishioners had become "vorticosi" from the alarm of the first shock.

The accounts given here and at Auletta, of the sounds heard at the same time, or rather before the shock, agree in the main. At Auletta, those who were in the town and survive, commonly used such words as "fischio sospirante," and the like, in describing the sound. Those down at the Locanda generally said it was like the "romore di carozzo" simply. The Padre described it as "ronzio e romore moderato." And when asked more minutely to describe it, he said it was "ingens fremitus retonans cum sibilatione." My final impression was, that the description of the people in the bottom of the valley, conveyed the notion of a more confused sound, than that of those on the summits, in the two towns; as if echoes or secondary sounds from the precipitous sides of the hills around had in some way been heard more by the former than the latter, with the primary sounds.

Descending with Padre Maucini, from the town to the road at the valley bottom, which is perhaps 100 feet above the bed of the Tanagro close beneath, I examined the little Casa Commnnale, a nearly new building (about three years old) a parallelogram of two stories (Fig. 153), nearly

cardinal (axial line 10° W of N.), built of rubble, with cut stone jamb dressings, and middling quoin stones, and with a heavy external stone staircase on the west flank. It was fissured in several places, and the fractures gave a wave-path of 120° W. of N., and an emergence of about 65° with the horizon. The emergence might be steeper, however, the direction of the fissures in the front, had been coerced in some degree, by the large proportionate surface, of cut stone jamb dressings.