the present symphony does not show anything sufficiently marked to call for record in that respect. It is singularly quiet and unpretentious, and characteristic of the composer, showing his taste and delicacy of sentiment together with his admirable sense of symmetry and his feeling for tone and refined orchestral effect.

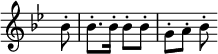

The contemporary of Mendelssohn and Sterndale Bennett who shows in most marked contrast with them is Robert Schumann. He seems to represent the opposite pole of music; for as they depended upon art and made clear technical workmanship their highest aim, Schumann was in many respects positively dependent upon his emotion. Not only was his natural disposition utterly different from theirs, but so was his education. Mendelssohn and Sterndale Bennett went through severe technical drilling in their early days. Schumann seems to have developed his technique by the force of his feelings, and was always more dependent upon them in the making of his works than upon general principles and external stock rules, such as his two contemporaries were satisfied with. The case affords an excellent musical parallel to the common circumstances of life; Mendelssohn and Sterndale Bennett were satisfied to accept certain rules because they knew that they were generally accepted; whereas Schumann was of the nature that had to prove all things, and find for himself that which was good. The result was, as often happens, that Schumann affords examples of technical deficiencies, and not a few things which his contemporaries had reason to compare unfavourably with the works of Mendelssohn and Sterndale Bennett; but in the end his best work is far more interesting, and far more deeply felt, and far more really earnest through and through than theirs. It is worth observing also that his feelings towards them were disinterested admiration and enthusiasm, while they thought very slightly of him. They were also the successful composers of their time, and at the head of their profession, while he was looked upon as a sort of half amateur, part mystic and part incompetent. Such circumstances as these have no little effect upon a man's artistic development, and drive him in upon his own resources. Up to a certain point the result for the world in this instance was advantageous. Schumann developed altogether his own method of education. He began with songs and more or less small pianoforte pieces. By working hard in these departments he developed his own emotional language, and in course of time, but relatively late in life as compared with most other composers, he seemed to arrive at the point when experiment on the scale of the Symphony was possible. In a letter to a friend he expressed his feeling that the pianoforte was becoming too narrow for his thoughts, and that he must try orchestral composition. The fruit of this resolve was the B♭ Symphony (op. 38), which was produced at Leipzig in 1841, and was probably his first important orchestral work. It is quite extraordinary how successfully he grappled with the difficulties of the greatest style of composition at the first attempt. The manner is thoroughly symphonic, impressive and broad, and the ideas are more genuinely instrumental both in form and expression than Mendelssohn's, and far more incisive in detail, which in instrumental music is a most vital matter. Mendelssohn had great readiness for making a tune, and it is as clear as possible that when he went about to make a large instrumental work his first thought was to find a good tune to begin upon. Schumann seems to have aimed rather at a definite and strongly marked idea, and to have allowed it to govern the form of period or phrase in which it was presented. In this he was radically in accord with both Mozart and Beethoven. The former in his instrumental works very commonly made what is called the principal subject out of two distinct items, which seem contrasted externally in certain characteristics and yet are inevitable to one another. Beethoven frequently satisfied himself with one principal one, as in the first movements of the Eroica and the C minor; and even where there are two more or less distinct figures, they are joined very closely into one phrase, as in the Pastoral, the No. 8, and the first movement of the Choral. The first movement of Schumann's B♭ Symphony shows the same characteristic. The movement seems almost to depend upon the simple but very definite first figure—

which is given out in slow time in the Introduction,[1] and worked up as by a mind pondering over its possibilities, finally breaking away with vigorous freshness and confidence in the 'Allegro molto Vivace.' The whole first section depends upon the development of this figure; and even the horns, which have the last utterances before the second subject appears, continue to repeat its rhythm with diminishing force. The second subject necessarily presents a different aspect altogether, and is in marked contrast to the first, but it similarly depends upon the clear character of the short figures of which it is composed, and its gradual work up from the quiet beginning to the loud climax, ends in the reappearance of the rhythmic form belonging to the principal figure of the movement. The whole of the working-out portion depends upon the same figure, which is presented in various aspects and with the addition of new features and ends in a climax which introduces the same figure in a slow form, very emphatically, corresponding to the statement in the Introduction. To this climax the recapitulation is duly welded on. The coda again makes the most of the same figure, in yet fresh aspects. The latter part is to all intents independent, apparently a sort of reflection on what has gone before, and is so far in definite contrast as to explain itself. The whole movement is direct

- ↑ See the curious anecdote, vol. iii. p. 413.