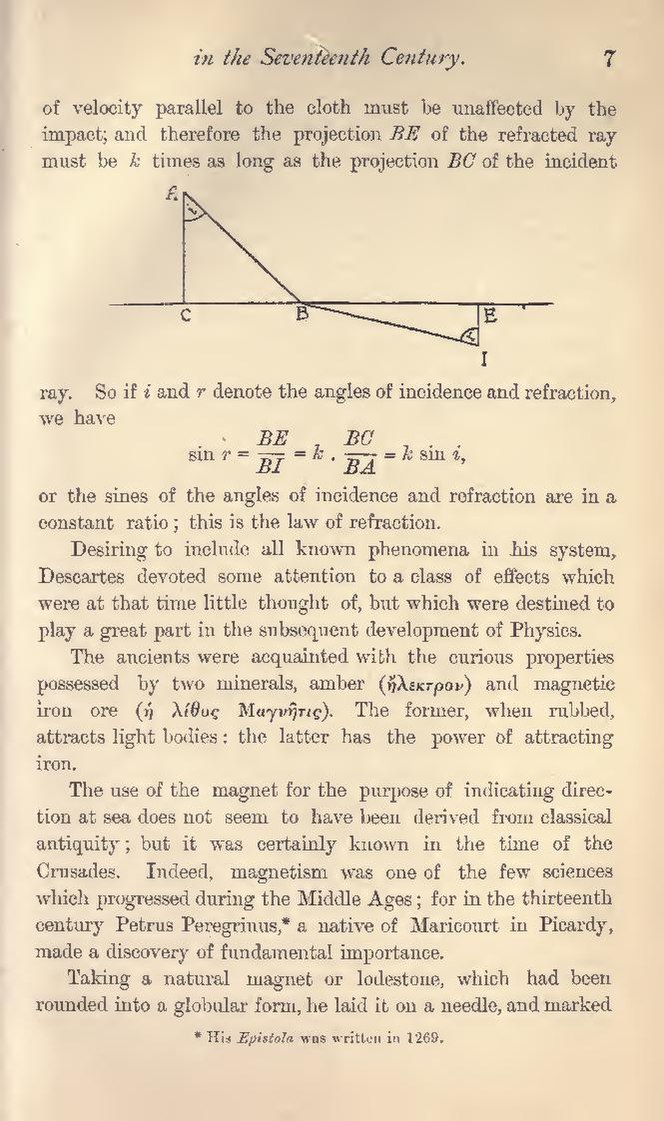

of velocity parallel to the cloth must be unaffected by the impact; and therefore the projection BE of the refracted ray must be k times as long as the projection BC of the incident

ray. So if i and r denote the angles of incidence and refraction, we have

,

or the sines of the angles of incidence and refraction are in a constant ratio; this is the law of refraction.

Desiring to include all known phenomena in his system, Descartes devoted some attention to a class of effects which were at that time little thought of, but which were destined to play a great part in the subsequent development of Physics.

The ancients were acquainted with the curious properties possessed by two minerals, amber (ἣλεκτρον) and magnetic iron ore (ἡ λίθος Μαγνῆτις). The former, when rubbed, attracts light bodies: the latter has the power of attracting iron.

The use of the magnet for the purpose of indicating direction at sea does not seem to have been derived from classical antiquity, but it was certainly known in the time of the Crusades. Indeed, magnetism was one of the few sciences which progressed during the Middle Ages; for in the thirteenth century Petrus Peregrinus,[1] a native of Maricourt in Picardy, made a discovery of fundamental importance.

Taking a natural magnet or lodestone, which had been rounded into a globular form, he laid it on a needle, and marked

- ↑ His Epistola was written in 1269.