himself, she should decide between them; and now Eriphyle, bribed by Polyneices with the fatal necklace given by Cadmus to Harmonia, persuaded him against his better judgment to set out on the expedition. Knowing his doom, he bade his sons, Alcmaeon and Amphilochus, avenge his death upon their mother, upon whom, as he stepped into his chariot, he turned a look of anger. This scene was represented upon the chest of Cypselus described by Pausanias (v. 17).

The assault on Thebes was disastrous for the Seven; and Amphiaraus, pursued by Periclymenus, would have been slain with his spear, had not Zeus with a thunderbolt opened a chasm into which the seer, with his chariot, horses and charioteer, disappeared. Henceforth he was numbered with the immortals and worshipped as a god. Near Oropus, on the supposed site of his passing, his sanctuary arose, with healing springs, and an oracle famous for its interpretation of dreams (Pausanias i. 34). The ruins of this temple, with inscriptions which identify it, have been discovered and preserved at Mavrodilisi, in the provinces of Boeotia and Attica. There was another temple dedicated to him on the road from Thebes to Potniae, and here was the oracle of Amphiaraus consulted by Croesus and Mardonius.

Homer, Odyssey, xi. 326; Herodotus viii. 134; Pindar, Olympia, vi., Nemea, ix.; Apollodorus iii. 6.

AMPHIBIA, a zoological term originally employed by Linnaeus to denote a class of the Animal Kingdom comprising crocodiles, lizards and salamanders, snakes and Caeciliae, tortoises and turtles and frogs; to which, in the later editions of the Systema Naturae he added some groups of fishes. In the Tableau Elémentaire, published in 1795, Cuvier adopts Linnaeus’s term in its earlier sense, but uses the French word “Reptiles,” already brought into use by Brisson, as the equivalent of Amphibia. In addition Cuvier accepts the Linnaean subdivisions of Amphibia-Reptilia for the tortoises, lizards (including crocodiles), salamanders and frogs; and Amphibia-Serpentes for the snakes, apodal lizards and Caeciliae.

In 1799[1] Alexandre Brongniart pointed out the wide differences which separate the frogs and salamanders (which he terms Batrachia) from the other reptiles; and in 1804 P. A. Latreille,[2] rightly estimating the value of these differences, though he was not an original worker in the field of vertebrate zoology, proposed to separate Brongniart’s Batrachia from the class of Reptilia proper, as a group of equal value, for which he retained the Linnaean name of Amphibia.

Cuvier went no further than Brongniart, and, in the Règne Animal, he dropped the term Amphibia, and substituted Reptilia for it. J. F. Meckel,[3] on the other hand, while equally accepting Brongniart’s classification, retained the term Amphibia in its earlier Linnaean sense; and his example has been generally followed by German writers, as, for instance, by H. Stannius, in that remarkable monument of accurate and extensive research, the Handbuch der Zootomie (2nd ed., 1856).

In 1816, de Blainville,[4] adopting Latreille’s view, divided the Linnaean Amphibia into Squamiféres and Nudipelliféres, or Amphibiens; though he offered an alternative arrangement, in which the class Reptiles is preserved and divided into two subclasses, the Ornithoides and the Ichthyoides. The latter are Brongniart’s Batrachia, plus the Caeciliae, whose true affinities had, in the meanwhile, been shown by A. M. C. Duméril; and, in this arrangement, the name Amphibiens is restricted to Proteus and Siren.

B. Merrem’s Pholidota and Batrachia (1820), F. S. Leuckart’s Monopnoa and Dipnoa (1821), J. Müller’s Squamata and Nuda (1832), are merely new names for de Blainville’s Ornithoides and Ichthyoides, though Müller gave far better anatomical characters of the two groups than had previously been put forward. Moreover, following the indications already given by K. E. von Baer in 1828,[5] Müller calls the attention of naturalists to the important fact, that while all the Squamata possess an amnion and an allantois, these structures are absent in the embryos of all the Nuda. An appeal made by Müller for observations on the development of the Caeciliae, and of those Amphibia which retain gills or gill-clefts throughout life, has unfortunately yielded no fruits.

In 1825 P. A. Latreille[6] published a new classification of the Vertebrata, which are primarily divided into Haematherma, containing the three classes of Mammifera, Monotremata and Aves; and Haemacryma, also containing three classes—Reptilia, Amphibia and Pisces. This division of the Vertebrata into hot and cold blooded is a curiously retrograde step, only intelligible when we reflect that the excellent entomologist had no real comprehension of vertebrate morphology; but he makes some atonement for the blunder by steadily upholding the class distinctness of the Amphibia. In this he was followed by Dr J. E. Gray; but Duméril and Bibron in their great work,[7] and Dr Günther in his Catalogue, in substance, adopted Brongniart’s arrangement, the Batrachia being simply one of the four orders of the class Reptilia. Huxley adopted Latreille’s view of the distinctness of the Amphibia, as a class of the Vertebrata, co-ordinate with the Mammalia, Aves, Reptilia and Pisces; and the same arrangement was accepted by Gegenbaur and Haeckel. In the Hunterian lectures delivered at the Royal College of Surgeons in 1863, Huxley divided the Vertebrata into Mammals, Sauroids and Ichthyoids, the latter division containing the Amphibia and Pisces. Subsequently he proposed the names of Sauropsida and Ichthyopsida for the Sauroids and Ichthyoids respectively.

Sir Richard Owen, in his work on The Anatomy of Vertebrates, followed Latreille in dividing the Vertebrata into Haematotherma and Haematocrya, and adopted Leuckart’s term of Dipnoa for the Amphibia. T. H. Huxley, in the ninth edition of this Encyclopaedia, treated of Brongniart’s Batrachia, under the designation Amphibia, but this use of the word has not been generally accepted. (See Batrachia.) (T. H. H.; P. C. M.)

AMPHIBOLE, an important group of rock-forming minerals, very similar in chemical composition and general characters to the pyroxenes, and like them falling into three series according to the system of crystallization. They differ from the pyroxenes, however, in having an angle between the prismatic cleavage of 56° instead of 87°; they are specifically lighter than the corresponding pyroxenes; and, in their optical characters, they are distinguished by their stronger pleochroism and by the wider angle of extinction on the plane of symmetry.

They are minerals of either original or secondary origin; in the former case occurring as constituents (hornblende) of igneous rocks, such as granite, diorite, andesite, &c. Those of secondary origin have either been developed (tremolite) in limestones by contact-metamorphism, or have resulted (actinolite) by the alteration of augite by dynamo-metamorphism. Pseudomorphs of amphibole after pyroxene are known as uralite.

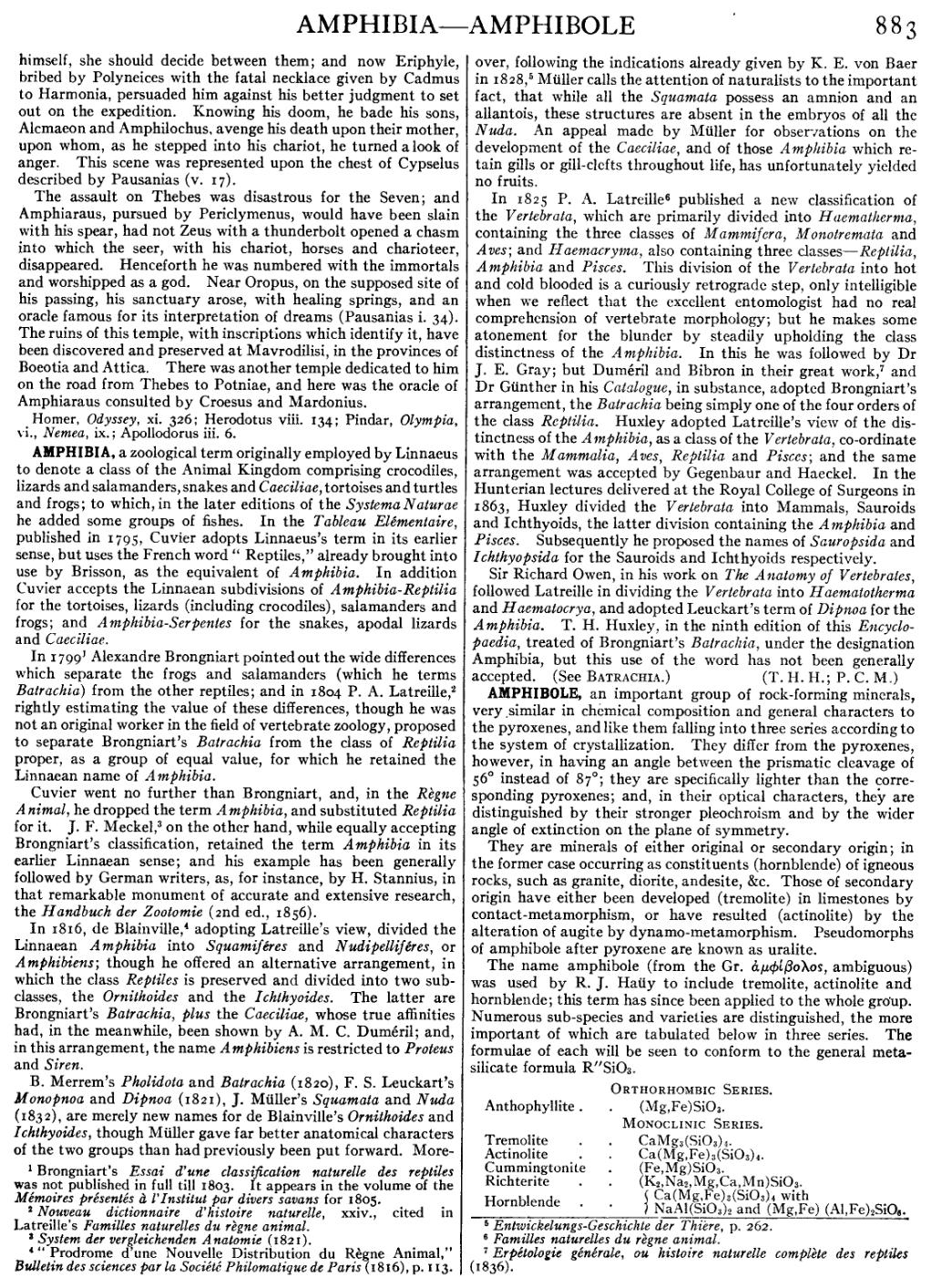

The name amphibole (from the Gr. ἀμφἰβολος, ambiguous) was used by R. J. Haüy to include tremolite, actinolite and hornblende; this term has since been applied to the whole group. Numerous sub-species and varieties are distinguished, the more important of which are tabulated below in three series. The formulae of each will be seen to conform to the general metasilicate formula R′′SiO3.

Orthorhombic Series. | ||

| Anthophyllite | (Mg, Fe)SiO3. | |

Monoclinic Series. | ||

| Tremolite | CaMg3(SiO3)4. | |

| Actinolite | Ca(Mg, Fe)3(SiO3)4. | |

| Cummingtonite | (Fe, Mg)SiO3. | |

| Richterite | (K2, Na2, Mg, Ca, Mn)SiO3. | |

| Hornblende | Ca(Mg, Fe)3(SiO3)4 with | |

| NaAl(SiO3)2 and (Mg, Fe) (Al, Fe)2SiO6. | ||

| Glaucophane | NaAl(SiO3)2⋅(Fe, Mg)SiO3. | |

| Crocidolite | NaFe(SiO3)2⋅FeSiO3. | |

| Riebeckite | 2NaFe(SiO3)2⋅FeSiO3. | |

| Arfvedsonite | Na8(Ca, Mg)3(Fe, Mn)14(Al, Fe)2 Si21O45. | |

Anorthic Series. | ||

| Aenigmatite | Na4Fe″9Al Fe‴ (Si, Ti)12O38. | |

- ↑ Brongniart’s Essai d'une classification naturelle des reptiles was not published in full till 1803. It appears in the volume of the Mémoires présentés à l'Institut par divers savans for 1805.

- ↑ Nouveau dictionnaire d'histoire naturelle, xxiv., cited in Latreille’s Familles naturelles du règne animal.

- ↑ System der vergleichenden Anatomie (1821).

- ↑ “Prodrome d'une Nouvelle Distribution du Règne Animal,” Bulletin des sciences par la Société Philomatique de Paris (1816), p. 113.

- ↑ Entwickelungs-Geschichte der Thiere, p. 262.

- ↑ Familles naturelles du règne animal.

- ↑ Erpétologie générale, ou histoire naturelle complète des reptiles (1836).