Fig. 5.

by means of simple formulae calculate quantities closely agreeing with those obtained from the seismogram. For example, if a body, say a coping-stone, has been thrown horizontally through a distance a, and fallen from a height b, the maximum horizontal velocity with which it was projected equals √(ga²/2b); or if the height of the centre of gravity of a column like a gravestone above the base on which it rests is y, and x is the horizontal distance of this centre from the edge over which it has turned, then the acceleration or suddenness of motion which caused its overthrow is measured, as pointed out by C. D. West, with fair accuracy by gx/y.

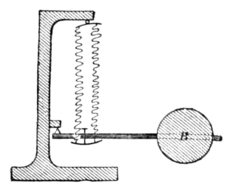

To measure vertical motion, which with the greater number of earthquakes is not appreciable, a fairly steady mass to which a multiplying light-writing index can be attached is obtained from a weight carried on a lever held by any form of spring in a horizontal position. Such an arrangement, for which seismologists are indebted to Gray’s seismograph.Professor T. Gray, is shown in fig. 6, in which B is the mass used as the steady point. This, when supported as shown, can be arranged to have an extremely slow period of vertical motion, and in this respect be equivalent to a weight attached to a very long spring, an alternative which is, however, impracticable. The value of these records, as is the case with other forms of seismographs, is impaired by pronounced tiltings of the ground.

Fig. 6.

We next turn to types of instruments employed to record earthquakes which have radiated from their origins, where they may have been violent, to such distances that their movements are no longer perceptible. In these instruments the same principles are followed as in the construction of horizontal pendulums, the chief difference being that the so-called steady mass is arranged to have a much longer period than that required when recording perceptible earthquakes. Instruments largely employed for this purpose in Italy are ordinary pendulum seismographs as in fig. 2. Instruments to record distant earthquakes.One at Catania consists of a weight of 300 kilos suspended by a wire 25 metres in length, the movements of which by means of writing indexes are multiplied 12·5 times. With pendulums of shorter length, say 2 metres, it is necessary to have a multiplication 80 to 100 fold by a double system of very light levers, in order to render the extremely slight tilting of their support perceptible. This arrangement, as devised by Professor G. Vicentini of Padua, will yield excellent diagrams of the gentle undulations of earthquakes which have originated at great distances, but for local disturbances, even if the bob of the pendulum acts as a steady point, the highly multiplied displacements are usually too great to be recorded.

In Japan, Germany, Austria, England and Russia horizontal pendulums of the von Rebeur-Paschwitz type are employed, which by means of levelling screws are usually adjusted to have a natural period or double swing of from 15 to 30 seconds. These pendulums are usually small. The swinging, arm or boom is from 4 to 8 in. long horizontally, and carries at its extremity a weight of a few ounces. A simple form, which is sometimes referred to as a conical pendulum, may be constructed with a large, sewing needle carrying a galvanometer mirror, suspended by means of a silk or quartz fibre as shown in fig. 7. To avoid the possibility of displacements due to magnetic influences, the needle may be replaced by a brass or glass rod. The adjustment of the instrument is effected by means of screws in the bed-plate, by turning which the axis o′o′′ may be brought into a position nearly vertical. As this position is approached the period of swing becomes greater and greater, and sensibility to slight tilting at right angles to the plane of o′o′′m is increased. The movements of the apparatus, which when complete should consist of two similar pendulums in planes at right angles to each other, are recorded by means of a beam of light, which, after reflection from the mirror or mirrors, passes through a cylindrical lens and is focussed upon a moving surface of photographic paper. The more distant this is from the pendulum the greater is the magnification of the angular movements of the mirror. With a period of 18 seconds, and the record-receiving paper at a distance of about 15 ft., a deflection of 1 millimetre of the light spot may indicate a tilting of 1100 part of a second of arc, or 1 in. in 326 miles. Although this high degree of sensibility, and even a sensibility still higher, may be required in connexion with investigations respecting changes in the vertical, it is not necessary in ordinary seismometry. A very sensitive modified von Rebeur instrument was employed by O. Hecker in his measurement of the variation in the vertical and of tidal earth tremors.

Fig. 7.

A type of instrument which has sufficient sensibility to record the various phases of unfelt earthquake motion, and which, at the suggestion of a committee of the British Association, has been adopted at many observatories throughout the world, is shown in fig. 8. With an adjustment to give a 15-second period, a deflection

Fig. 8.

of 1 mm. at the outer end of the boom corresponds to a tilting of the bed-plate of 0′′·5, or 1 in. in 6·4 m. The record is obtained by the light from a small lamp reflected downwards by a mirror so as to pass through a slit in a small plate attached to the outer end of the boom. The short streak of light thus obtained moves with