it, the plant discovers that it has been deceived, and, after bending for a time, it unbends and becomes straight again.

The bending, which enables a leaf to seize a twig, is not the only change which the stimulus of a touch produces. The leaf-stalk swells and becomes thicker and more woody, and turns into a strong, permanent support to the plant. The thickening of the leaf-stalks is to be made out in Fig. 2, which represents a shoot of clematis, bearing two leaves, each of which has seized a twig; in one of the leaf-stalks this thickening has commenced, and is fairly evident. The thickened and woody leaf-stalks remain in winter after the leafy part has dropped off, and in this condition they are strikingly like real tendrils.

The genus Tropœolum, whose cultivated species are often called nasturtiums, also consists of leaf-climbing plants, which climb like clematis by grasping neighboring objects with their leaf-stalks.

In some species of Tropœolum we find climbing organs developed, which can not logically be distinguished from tendrils; they consist of little filaments, not green like a leaf, but colored like the stem. Their tips are a little flattened and furrowed, but never develop into leaves; and these filaments are sensitive to a touch, and bend toward a touching object, which they clasp securely. Filaments of this kind are borne by the young plant, but it subsequently produces filaments with slightly enlarged ends, then with rudimentary or dwarfed leaves, and finally with full-sized leaves; when these are developed they clasp with their leaf-stalks, and then the first-formed filaments wither and die off; thus the plant, which in its youth was a tendril-climber, gradually develops into a true leaf-climber. During the transition, every gradation between a leaf and a tendril may be seen on the same plant.  Fig. 3.—Bignonia. An unnamed species from Kew. It is not always the stalk of a leaf which is developed into the clasping organ; the bignonia-leaf shown in Fig. 3 bears tendrils at its free extremity. And in other plants tendrils are formed from flower-stalks, in which the flowers are not developed, or the whole stem of the plant or a single branch may turn into a tendril. In one curious case of monstrosity, what should have been a prickle on a sort of cucumber, grew out into a long, curled tendril.

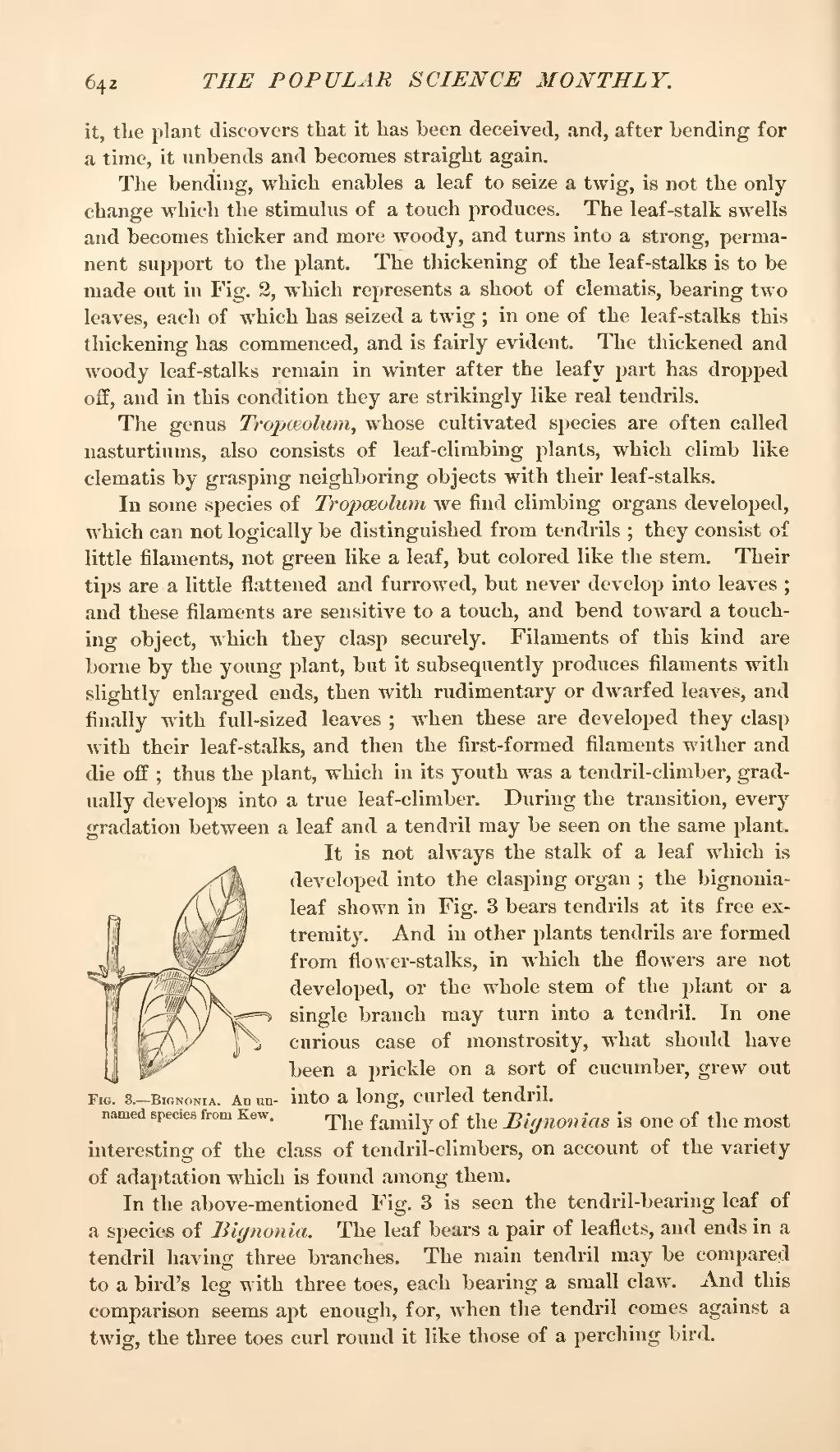

Fig. 3.—Bignonia. An unnamed species from Kew. It is not always the stalk of a leaf which is developed into the clasping organ; the bignonia-leaf shown in Fig. 3 bears tendrils at its free extremity. And in other plants tendrils are formed from flower-stalks, in which the flowers are not developed, or the whole stem of the plant or a single branch may turn into a tendril. In one curious case of monstrosity, what should have been a prickle on a sort of cucumber, grew out into a long, curled tendril.

The family of the Bignonias is one of the most interesting of the class of tendril-climbers, on account of the variety of adaptation which is found among them.

In the above-mentioned Fig. 3 is seen the tendril-bearing leaf of a species of Bignonia. The leaf bears a pair of leaflets, and ends in a tendril having three branches. The main tendril may be compared to a bird's leg with three toes, each bearing a small claw. And this comparison seems apt enough, for, when the tendril comes against a twig, the three toes curl round it like those of a perching bird.