CHAPTER VI

PASHPATTI

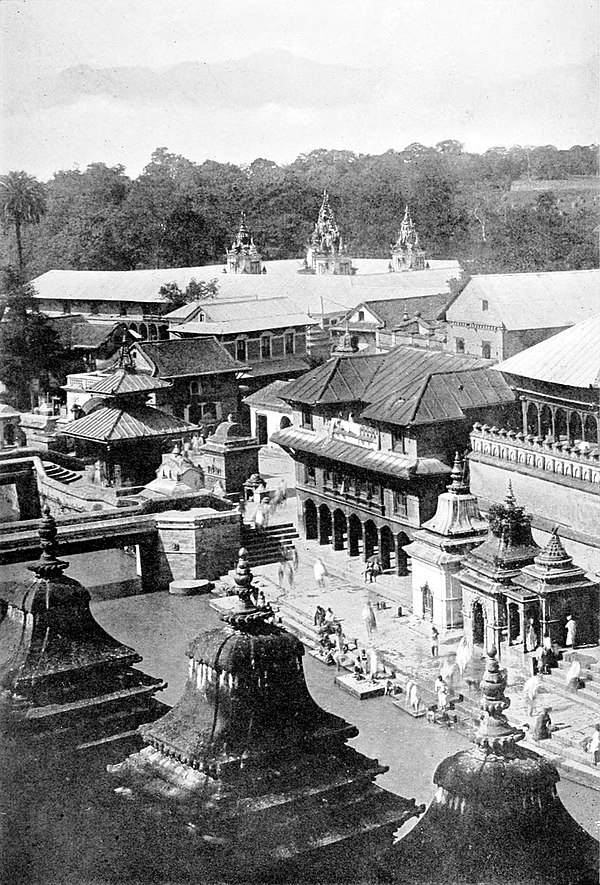

The Doorway of Death—Its Buildings—The Daily Devotees—Women Pilgrims—The Burning-Ghat.

Pashpatti is a picturesque collection of temples and shrines about three miles northeast of Katmandu, and on the banks of the Baghmatti River. Here this stream passes through a narrow gorge, which may be appropriately called the "Valley of Shadow," for Pashpatti is truly the doorway of death. So holy is this place that the one great desire of the Hindu is to gasp out his last breath on the steps of the "ghat," with his feet lapped by the swirls and eddies of the sacred stream. Through sad and dreary existences many of these people toil, unrelieved by any ray of happiness, drudging and starving, but experiencing their one and only thrill of joy in this life as they are passing out of it—another view of that noble thought of Lucan, "Victurosque dii celant, ut vivere durent, Felix esse mori." To any but an Oriental, the idea of being dragged from one's death-bed, carried many miles in a jolting dooly, and then left to fight the last vain struggle on uncomfortable stone steps, with the extremities in cold water, is not an attractive one. But to the inhabitant of Nepal, and from regions far into the plains of India, this final act of penance is felt to be a fitting preparation for that mysterious journey on the other side of the River. And so lying about in corners and recesses are people in the last stage of some fell disease, groaning out their lives, tortured in body but happy in mind, because they have been spared to die within the holy precincts of Pashpatti. When this event actually takes place, the funeral pyre is built on one of the flat buttresses projecting into the sacred stream, and in the gloaming one may see the smoke drifting into the dark recesses of the "Valley of the Shadow," and the turrets and gilded roofs lit up by the glow from the fire of the dead.

But although this is the principal object of Pashpatti, it is pleasant to turn away from the sombre picture thus presented, and see it in the cheerful light of the early morning, when it teems with movement and life. For soon after dawn, as the sun glints on the golden finials of this garden of pagodas, all the people living in the neighbourhood come down in many-coloured garments to perform their prayers and ablutions before commencing on the duties of the day. The buildings are grouped on the west bank of the river, which is crossed by two romantic old bridges, like a combination of Venice and Benares in miniature. They consist mainly of courts and squares arranged in several stories or levels, and connected by frequent flights of stone steps. Picturesque pyramidal roofs cover the temples, the most important one rising above the others into a brilliant effect of fretted wood and fluted gold against the blue sky and distant snows. The courts are filled with images and shrines which have been consecrated at different periods, while before the great sanctuary is the colossal image of a kneeling bull (Nandi), executed in copper and heavily gilt. It is hardly necessary to add that the majority of devotees believe this huge animal is wrought in solid gold.

Such is the bright and barbaric aspect of Pashpatti—the holiest temple of Nepal—of such great sanctity that a pilgrimage to it is deemed an act of purer devotion than the observance of any similar rites prescribed by the Hindu religion. Its situation gives it a mystery which may account for some of this, as the gorge forming the background is a gloomy precipitous cutting through which the holy river silently and solemnly flows. Excavated in the face of the cliff high above the water, and reached only by some primitive means devised by the occupant, are several dark-looking cells in which certain fakirs are said to live and die—

"And next the shryne a pit then doth he grave,"

but it is a place of shadows, and the gay pageant below is commencing.

Quite early the edge of the water is taken up by small groups of picturesquely robed men engaged in the occupation of selling flowers and other offerings to the devotees. Then begin to arrive, as the sun lights up the scene, many men in various bright attires, followed by bevies of women and girls in the gayest of robes. Mixed bathing is the order of the day, and all is decorum, the robing and disrobing being performed in that clever manner only to be accomplished by the Oriental. Soon the crowd grows thicker, and the gay and gorgeous scene—duplicated in the rippling waters of the Baghmatti—becomes a kaleidoscope of bright colours. It seems almost impossible to separate the picture into its individual particles, but it may be attempted. One sees a class of "Sadus," men dressed from head to foot in garments of blood-red, and another religious order is distinguished by the more usual saffron colour. A fakir strolls by nearly unnoticed, although clothed in a startling overall of leopard skins. Some of the boys are most vividly garbed, and an urchin in a combination of artistic purples catches the eye. But gay as the men are dressed, they are completely put into the shade by the

GENERAL VIEW OF PASHPATTI, THE "PLACE OF THE DEAD"

The sacred river runs through a picturesque gorge at this spot.

A PICTURESQUE CORNER IN THE HOLY PILGRIMAGE PLACE OF PASHPATTI.

This sanctuary consists of a collection of temples and shrines on the Baghmatti River. Devotees come to Pashpatti to die with their feet lapped by the sacred stream