CHAPTER XIX

A Great Maori Carnival—Interviewing a Much-Married Prophet—In a Hauhau Village—A Call on King Mahuta

At Ngaruawahia, once the capital of the Maori kingdom,—a very limited monarchy confined to the Waikato country,—is held once a year a great Maori carnival. Here, at the junction of the Waikato and Waipa Rivers, from ten thousand to twelve thousand natives and Europeans congregate on St. Patrick's Day to see exciting war canoe races, comic canoe hurdles, stirring hakas, and the graceful poi.

From the north and the south, the east and the west, people travel in long excursion trains to witness the chief Maori festivity of its kind. Especially from Auckland, about seventy-five miles distant, thousands of excursionists journey to Ngaruawahia in passenger coaches and goods trucks.

On the day I left Auckland to see the carnival I reached Ngaruawahia about noon. At that hour the banks of the Waikato were thronged by thousands of people and hundreds more swarmed through the town, and nowhere more so than inside and outside the bars of the two hotels. The whole was a moving panorama of colors, ill matched, many of them, but worn none the less proudly for that by their Maori owners.

Heading for the forty side-shows in the grove, I first passed a stand stacked with bottled mussels and smoked schnapper, the latter one of New Zealand's most popular sea-fish. A white hawker was selling these wares to the Maoris, two of whom stood by eating fish with their fingers. Below this was another schnapper stand, also well patronized by natives. Had there been a shark stand in the neighborhood it likewise would have prospered, for Maoris are fond of shark flesh.

Not all the Maoris about stood eating in the highway. Many were dining in roughly furnished tents. Here also was fish in abundance. And here, too, were table manners in great variety. One of the best examples of table etiquette was provided by a Maori man. He was using a knife and fork, but suddenly tiring of them, he put them down, and seizing a potato in his fingers he ate it in true primordial fashion.

Everywhere I went there were Maoris, many of them being men and women of great girth and weighing two or three hundred pounds and upward. Hundreds of both sexes were smoking pipes or cigarettes. It was a happy Maori crowd. Hand in hand, three girls came hurrying across the green. On the same track followed two youths awkwardly leading a big girl between them. Here and there gossipy mothers carried babies papoose fashion, in shawls on their backs; and here grizzled age made merry and flushed with youth again.

All the Maoris, from babies to grandfathers and grandmothers, were well dressed, though not always with good taste. There were yellow dresses and green,

TATTOOED MAORI WITH HUIA FEATHERS IN HAIR

red, white, and blue dresses. There were loose-fitting blouses and diffusive skirts, and as it were a reproach to these, close-fitting gowns on young wahines.

"Did you see that Maori woman in a hobble skirt?" a friend asked me.

"No; where is she?" I inquired.

"She just disappeared in the crowd with a bloke," answered he.

Soon after I heard a voice exclaim: "Get off my dress."

The speaker was a big Maori woman, and as she gave this command she struck a white woman, who accidentally had trod on her skirt.

There were ribbons and sashes of all hues; and the premier color of Ireland was not the least of these. Incongruities of dress were common. Although the day was hot, one woman wore an ostrich boa, with a gayly-colored parasol raised above it, and another woman carried a fur muff. Occasionally there was a flash of the truly picturesque,—one, a girl poi dancer wearing a flax mat, another, a warlike man bared to the waist and kilted with flax. With young men colored waistcoats found favor.

Ornaments were at all places conspicuous, especially large greenstone pendants and greenstone earrings with black ribbons attached. One pendant looked like a papercutter. There also were silver-tipped boar tusks; in large frames photographs of men; cheap, gaudy jewelry; metaled and tinted flower and leaf; and feathers—plumes of the huia, the duck, the pheasant, and the long, slender red tail feather of the amokura. More lasting than all these adornments were the tattooed chins of the women. The decorations of the men also were noticeable, some of the elder ones even wearing earrings; but the women carried enough ornaments to furnish a second- or third-rate jewelry store.

"Let me know as soon as you see a hongi," I said to my friend. "I want to see every kind of hongi there is."

"There they are. Quick! before they've finished," shouted my companion.

"They" were two old Maori women, and they were engaged in the prosaic occupation of rubbing each other's nose. They were squatting on the ground, their hands were clasped, tears rolled down their cheeks, and moans escaped from their slightly moving lips. They had long been separated, and were simply greeting each other in the most approved Maori fashion.

For several minutes this singular greeting lasted, two flat ihus pressing each other all the while. Of the hundreds of people about them these two were apparently unmindful. Finally they arose, and one, immediately grasping the hand of a native man seated near her, started another hongi.

Compared with some nose salutations, the hongi just witnessed was a mild exhibition. One that I saw later between an elderly Maori man and a youth was more energetic. These two fairly howled as they condoled

A HONGI

with each other. After a prolonged effort they had an intermission, in which they wiped their tears away. Then they started all over again.

All that day at Ngaruawahia there were hongis, and had we reached the town in the early morning, we should have seen hundreds of such exchanges of affection. At purely Maori meetings there are remarkable nose-rubbing performances. In fact, they are such days for the nose that it is a wonder the rest of the face does not get jealous at this show of esteem. At these huis the hosts, or the inhabitants of the villages where they are held, fall into line after the speeches of welcome and responses, and as the visitors pass by, hosts and guests rub noses. Often one man will rub hundreds of noses in a single day. Necessarily, these fraternal displays are not individually so prolonged as at family reunions or small parties of relations and friends.

There are, I found, several kinds of nose-rubbing, or, rather, preliminaries thereto. After two noses have found a proper setting, perhaps with some skirmishing for position, there is little or no rubbing. Some noses are so expert in their manœuvres that they instantly find a satisfactory resting-place; others, not so experienced, or having only a slight acquaintance with a friendly nose, feel their way or proceed cautiously, like an Indian tracker on a stealthy mission.

Fortunately for the Maori, with few exceptions his nose is flat. Thus it is admirably adapted for hongis, and its owner regards it as the most beautiful nose in the world. All hail, then, to the Maori nose! For it a laurel wreath, a gold medal, or a blue ribbon.

Beyond the nose-rubbing group stretched the tents and booths of the side shows. At the stands we could have bought almost anything from flashy jewelry and alarm clocks to bandanna handkerchiefs and potato-parers. Above one pyramidal booth floated a small American flag. How dignified it looked in that place of noise and jostle!

Here, too, were the "Petrified Lady"; "take-all-comers" wrestlers and boxers; a "professor" wildly proclaiming the "wonders" of a dog show; and, in adjoining tents, a fat man and Darwin's "Missing Link," both from America.

Of course, there were games of chance, and two merry-go-rounds with rumbling music. More than half the passengers on the merry-go-rounds were Maoris. Not all were able to ride the horses. I saw one Maori girl make three unsuccessful attempts to mount a painted steed.

Down by the Waipa stood an old unpainted building which evidently was the headquarters of a watermelon vendor. From it I frequently saw Maoris emerge hugging watermelons. One two-year-old girl, dressed neatly in white, walked about holding half a melon to her breast. She did not care to associate with pakeha children or their parents, and every time one spoke to her, she cried.

It is doubtful if anywhere else in the world there are canoe races superior to those held on the Waikato River, at Mercer and at Ngaruawahia. The canoe contests of Washington and British Columbia are usually exciting enough for anybody, but the crews are limited to about a dozen men. In the long Maori war canoes from thirty to forty men flash paddles as they are urged forward by the rhythmic cries of their captains. In the Society Islands, canoes and crews are about equally large, but I would hesitate to back the Tahitians or Mooreans in a contest with the hardier Maoris.

As is customary, the Ngaruawahia regatta was opened on this day with a canoe parade. The first aquatic event was a canoe hurdle race for men. There were three hurdles, placed several rods apart, and each consisting of a pole raised about a foot above the river. Over these obstacles the contestants had to drive their wakas, and then paddle for a short distance to the winning stake.

Each crew was limited to two men, and as they paddled they sat in the back of their light canoes, thus raising the long bow above the hurdle. As the nose of the canoes glided over the top of the pole the paddlers rushed forward. Those who had selected the psychological moment and were able to maintain their advantages got safely over. Others less fortunate lost their equilibrium or were not active enough, and slid back or were capsized.

When well timed, and movements were not too quick or too slow, the weight of the crews forced the canoes over as smoothly as the passage of logs down a chute. When the calculations were wrong, another start had to be made, and always amidst the laughter and badinage of the multitude. In the first hurdle race the six canoes entered were close at the finish, and but one was capsized.

Following this contest was a mirth-provoking women's hurdle. There were two wahines to each canoe, and at the first pole the canoes pressed each other closely. Pare and Mere, the leaders, wriggled over the hurdle after the other canoes, sliding along the pole, had crowded them to one side and nearly sent them backward. The second crew got over at their second attempt, and found themselves parallel with the pole, with their craft headed shoreward and half full of water. Baling it out, they started again, and reached the barrier with six inches of water in their canoe.

The third crew was fated to be the laughing-stock of the crowded banks. At the first three attempts to get over the first hurdle they were forced back, and on the third failure the forward stroke fell into the river. The fourth effort was as ignoble as its predecessors. The fifth was the worst of all. The canoe capsized, and both women went into the stream. Two canoes manned by native men went to their aid and righted the canoe. Seeing now that they were hopelessly out of the race, the discomfited twain abandoned further trials.

The next hurdle was scarcely less amusing. This was an over-and-under hurdle for men, the crews being

WOMEN'S CANOE HURDLE

required to pass under the hurdles and send their canoes over them. One man negotiated the first hurdle successfully, but his opponents were so close together at that point that they piled up in one tangled heap. While they were extricating themselves the first canoe got well away, and won.

There were two war-canoe races, three canoes competing in each. Two of the canoes were eighty feet long, and were advertised to carry thirty-six men. The smallest canoe carried twenty men. The courses were three miles long and both events were handicaps. The first race was the Ngaruawahia Handicap, in which the smallest canoe was given three hundred and fifty yards' start; the Te Waonui a Tane's crew of thirty-two was allowed one hundred and ten yards' start of the Tangitekiwi, the scratch canoe, which carried thirty-six men.

The bows of the canoes were boxed In and when the crews were seated, their gunwales were a very few inches above water. In the centre of the largest canoes stood a feather-bedecked captain, who, from a slightly raised platform, prepared to flourish his arms, to cut the air with his taiaha (sword), and to shout and chant encouragement to the paddlers.

As the canoes started they were followed by a fleet of small steamers and launches loaded to capacity with excursionists. As they moved swiftly down the Waikato, they were hailed by excited Maoris ashore. These vied with the canoe captains in the fervor of their demonstrations,—men, women and children joining in the clamorous chorus.

The large canoes strained hard to overtake the flying Tauanui, yet it was impossible appreciably to diminish the gap. But meanwhile what amazing paddling we witnessed. So rapidly, so rhythmically did the paddles rise and fall that the canoes looked like great marine monsters with long rows of palpitating gills. Through it all the captains balanced themselves on their little elevations, singing and gesticulating. At one moment they were exhorting the forward paddlers; then, turning, they addressed the stalwarts aft. Their bodies swayed in rhythm with the glinting blades; their straining eyes noted every gain and loss, which they emphasized by brandishing taiaha or hand aloft; and as they lunged forward the canoes seemed to respond like trained living creatures.

On the eastern borders of the little-known Urewera country I sought the prophet Rua, the most talked-of Maori of the day. I had heard so many strange stories about him that I resolved to interview him, if possible. Just where I should find him I did not know, but I knew that he could not be more than one or two days' journey into the mountainous regions back of Opotiki, a Bay of Plenty town which Rua often visited. Here, I had heard, he had walked up and down Church Street

with a money-box, buying everything he or his wives fancied.

AT THE FINISH LINE

Yes, his wives! For when I saw him he had seven, and no one in Opotiki knew when he would take unto himself another. But most wonderful of all, so exemplary are these seven that they are not jealous of each other! So Rua assured me in a most matter-of-fact way when, after four days of fruitless efforts, I cornered the long-haired predictor.

While, according to Caucasian standards, Rua was morally a bigamist, he was not legally such, having taken his wives according to Maori custom. Doubtless many other Maori women would have been proud to join the prophet's household; but Hurinui Apanui, foremost of living Urewera chiefs, told me Rua would take no more wives. From Hurinui, too, I learned that in his polygamous views Rua was somewhat selfish; his "Follow me" was not all embracing. He would not permit his followers to have more than one wife at a time, although, Hurinui assured me, "he allows them to change their wives when they want to."

I reached Opotiki at an opportune time. The Native Land Court was sitting there adjusting the large transfers of land Rua had made to the State in behalf of his followers. The town was full of Maoris, and on the main streets they were more numerous than Europeans. Half of Urewera appeared to have moved into the town. The hotel bars were thronged with Maoris; they flocked about the shops; and they were scattered about in tents.

The majority of the Maoris were well dressed, though by no means faultlessly. Some of the make-ups were clownish. Many of the women were gorgeous in colors and extravagantly bedecked with greenstone ornaments. Some were barefooted, but a large percentage were shod. Not a few squatted in rows on the sidewalks in front of stores; others walked about and peered into shop windows. Tattooed chins were numerous, and pipes overhung a good number of them. From lobes hung earrings of greenstone decorated with gold and silver, some hanging direct from the ear, others pendent on black ribbons fastened in the ear. One woman had silver-mounted earrings and two gold-mounted brooches.

Among the women were odd inconsistencies of dress. Brilliancy was in close company with sombreness; colors that should have been strangers to each other hobnobbed together on skirt, waist, and hat; slouch hats bordering on the disreputable looked dull beside flaring red or bright green; and flashy neckties were set on gloomy blouses.

Here came one woman with a blue skirt, a red waist, and bright yellow hat trimmings sufficient for at least two hats. Beside her walked a woman carrying a baby on her back in the folds of a big colored shawl, and with a large striped flax kit in one hand. Another woman approached me wearing a boyish-looking green hat, held in place with long brass pins; a red hair-ribbon and a red tie; a brown waist; and black skirt and black shoes, or boots, as they call shoes in New Zealand. The waist had long, flapping lace sleeves, matched in color by the flax kit, or shopping-bag, she carried. She was met by another woman wearing a lavender gown, a big red sash, a red neckcloth, and a straw hat with a liberal amount of white trimming.

Most interesting of all was a row of Rua's wives, brightly arrayed, and occupying the whole width of the walk as they strolled up the street with all eyes on them.

All the native men wore European clothes. Riding habits were common, and a number had feathers in their hat bands. A few followers of Rua had hat-pins thrust through their long hair, and a humpbacked zealot had a back comb. Many men were as incongruous in their attire as the women. There were yellow and orange neckcloths, and green, blue, red and lavender socks over riding-breeches; while garters of various hues encircled thick calves.

Every day for a week there were additions to this exhibition of colors and sartorial absurdities. They entered the town on the gallop. Seeing two wagonloads of men and women dressed in their best driving into Opotiki on the run, I said to my half-caste Maori guide, "Those Maoris drive like Tahitians."

"Oh," replied he with a touch of ennui, "they are just making a show of themselves."

Few of the male visitors failed to patronize a hotel bar soon after reaching the town, but not many were allowed in the other hotel rooms, and as a rule no Maori women. At the hotel where I was staying a Maori man sat down in a wicker chair in the hallway, just as the landlady entered.

"Here, here!" said she, clapping her hands, "these chairs are for the pakeha."

Another Maori man brought in a native woman, and straightway the landlady was upon him.

"You must n't bring her through here," she protested. "You know it is n't allowed."

"All right," grunted the man, and then he passed through despite the order.

At this hotel noisy Maoris were drinking every day, and one of them fought a white man. The Maori is a convivial spirit, and nowhere more so than in a bar. Maoris are always willing to "shout," but after they have treated, some will say, "I shouted for you, now you shout for me."

"Where can I hear Maori singing?" I asked Mokomoko, pilot for a steamship company.

"If you want to get a Maori to sing," he advised, "give him a beer."

Of all these thirsty natives the most frequent visitor to Opotiki's "pubs" was Tamaikoha, an aged ex-cannibal. With pipe in mouth, this wrinkled Polynesian shuffled into the commercial room of the hotel one Sunday. Halting at the door, he looked appealingly at the inmates and passed a forefinger across his throat. Did he mean to convey by pantomime that he intended to commit suicide? No; he was thirsty! and the bar was closed.

"That man is more than ninety years old," said an Opotiki merchant present, "and he has eaten pakeha."

Tamaikoha was not ashamed to acknowledge that he was once a cannibal, and he even joked about that fact. "You are no good for me," said he to a solicitor. "You are too thin and yellow."

When in Opotiki the old man divided his time between two public-houses. To one he always went early in the morning, and I often saw him crouching on the walk outside. Later he would appear at the hotel where I lodged, and frequently squat on the floor before the bar. There I saw him finishing a haka one morning, a sure evidence that he had been given or promised a "beer."

Tamaikoha was a ludicrous mixture of the solemn and the comic. He was never too solemn to become comical, nor too comical to lapse quickly into solemnity. He was a walking caricature. He wore a round slouch hat that meagrely shaded a stubby white beard and side whiskers. Over summer trousers that looked as if they had been thrashed about in a greasy dust heap, and an unbuttoned vest with a liberal exposure of neck above it, he wore a dull-colored overcoat. He was barefooted, and walked slowly, usually with hands behind back; which, with bowed head, clothed him with a judicial, studious air.

I had not been long in Opotiki until I heard of Rua. He had taken a cottage, and four of his wives occupied it with him. He was the busiest man in town. More than a hundred thousand dollars had passed through his hands a short time before, and many thousands more were soon to be paid to him. He had proved himself to be more successful as business agent for the Urewera tribe than as its prophet, and he was regarded by his supporters and clients as a great man. In the Bay of Plenty district he was in truth the man of the hour. Cognizant as he was of his power and prestige, would he be pliable in the hands of one who had come to ask him meddlesome questions? This appeared so doubtful that, to influence Rua, I had solicited an introduction to him from the Native Minister.

Before I called on Rua, I heard astonishing tales about him. I learned that a few years ago he was an obscure laborer, who later professed healing virtues, and cured many Maoris of their ills. Puffed with success, he proclaimed himself a second Christ, and even imagined he had a facial resemblance to the Saviour. Turning to prophecy, he gathered a large following, who believed in him implicitly.

As an instance of his influence, Rua announced that on a certain day he would walk on the river at Whakatane. A great crowd collected to see him. Standing before it, Rua asked:—

"Do you believe I can walk on the water?"

"Yes," shouted a number of natives.

"Well," said Rua, "so long as you believe I can do it, that is all that is necessary."

Rua's predictions were remarkable, but not more so than the blind trust placed in them by his adherents. For a certain date he prophesied an earthquake. Luckily for him there was a shock in the South Island that day. It was far from where it had been promised, but

RUA AND FOUR OF HIS WIVES

Rua's face wore an I-told-you-so expression despite the miscarriage, and he received wide and loud acclaim from the Maoris.

At another time Rua said that the late King Edward VII was coming to Gisborne to visit him on an appointed day. In this brazen prophecy such trust was placed that a number of natives bet heavily with whites that the King would come. One Maori bet a buggy and two draft-horses against $250; another native put one horse against $125. When the King did not appear the first Maori wanted his horses back, and even tried to steal them, the winner told me.

As usual, Rua had an excuse when the monarch failed to arrive. The King was too sick, he explained; later he blamed Halley's comet for the non-arrival; and when the King died, some Maoris declared he had been caught up in the comet's tail!

A prediction that had more effect was that respecting a tidal wave seventy-five feet high, which was to invade the Bay of Plenty. Rua, I was informed by Hurinui Apanui, advised the Maoris of that locality to sell all their possessions before the wave arrived, and many did so. When the natives decided to sell their lands to the State, Rua dreamed, and foresaw for himself wealth and great honor. Beside the picture he drew prophecy was tame. So, acting as his people's agent, he sold thousands of acres of land. With the receipts therefrom in hand the unique village he had established in the far interior lost its magnetic interest, and with many of its inhabitants the seer moved fifty miles nearer civilization and founded Waimana, which, unlike Maungapohatu, could be reached by carriage.

When he first emerged from obscurity, "Rua did not like to be stared at; now he doesn't mind," one who knew him told me. "But if you go to his settlement," this man warned me, "don't stare too long at his wives. Rua is very jealous."

The arrival of the Native Minister's letter of introduction was delayed, and tiring of waiting for it, I determined to face Rua without it.

"How shall I know Rua when I meet him?" I asked a man at the hotel.

"Oh, you will know him easy enough," he replied. "He is wearing red socks."

So out I went to look for a pair of flaming socks. It was not long before I saw a pair sticking out of two brown shoes, and as they were the only red socks on the street, I decided that they were Rua's. The man above these socks was large. He wore riding-breeches, a blue, unbuttoned coat, a colored shirt, and a blue tie. Above his bushy face was a soft straw hat with a white-headed pin stuck through it. This was Rua with his hair "done up," and he was standing on a corner of the main street, talking with Maoris.

I did not know whether he could speak English or not, for my informers were disagreed on this point; therefore I approached him cautiously, and inquired of a Maori more civilized-looking than the others.

"Yes, Rua speaks little English, not very well," he answered me.

I told him what I wanted, and he explained it to the prophet. In reply, Rua said he would meet me at that corner at five o'clock that day. I thought then that I should have no difficulty in persuading him to talk. But I did not know Rua.

At five I was at the corner, but Rua was not there. "Just like a Polynesian," I concluded, thinking of appointments with Tahitians the year before. Presently I spied the red socks at the other end of the street, and with them was a red hair-ribbon. It was Rua with one of his wives—she displaying a long gold chain necklace—walking leisurely up the thoroughfare. At my corner they sauntered into a store.

Apparently the prophet had not seen me, and presuming that the two wished to shop there, I resolved to let them do so before reminding Rua of his appointment. Fifteen minutes' waiting made me impatient and suspicious, and I entered the store to find him doing nothing, so far as I could see.

When Rua saw me, he raised his eyes and asked the storekeeper, who for the moment acted as my interpreter, what I wanted. On this being explained to him, the prophet replied that he was too busy to see me unless I had business to transact with him. There were many land titles to be adjusted, said he, and he could not spare me any of his time unless money were involved. This was discouraging, but there was more to come, and it came bluntly. It was: "What you want is nothing." And this cruel thrust from one claiming resemblance to the Great Teacher!

I had been told that the man had a certain Jewish cast of countenance. If he ever had had such a cast, he certainly had lost a lot of it before I saw him. To me he was just plain Polynesian, with a broad face and a broad, flat nose.

I knew he could afford to give me the time I wanted if he chose to do so, and I declined to cease my importunities. It was then or never. As I continued arguing my case, Rua rose, and throwing out his hands in true oratorical fashion, addressed the storekeeper. He wore a shrewd look, and he had the air of the most independent of men. Probably he regarded my request for a claim on his hours as rash and unwarranted. At first he seemed amused by it, but at last he agreed to meet me two days later, on Sunday afternoon, provided it rained; otherwise he would go to Waimana. If he went to Waimana he would meet me Monday night.

It did not rain, and at six o'clock Monday evening he promised my interpreter to see me at this corner store at eight that same evening. At that hour there was no sign of him, nor half an hour later. By that time it was not hard to conclude that the prophet was long on promises, but short on their fulfillment. Why had he evaded me again? I put this question to a merchant the next day.

"Oh," he explained, "he may have got into an argument with a lot of natives, and forgot. There he is now, in that hotel, having a discussion."

After this failure of Rua to keep his appointment, I almost despaired of interviewing the wily exhorter. Fortunately the next day's mail brought the Native Minister's introductory letter, and with it I prepared for the final attack. Getting a good interpreter, I started for Rua's cottage. In turning off Church Street, I saw him coming round a corner in his shirt-sleeves. He was aflame with a red tie, red suspenders, and red socks, moderated by a bright pink sash.

Giving him the Minister's letter, I explained that I had heard so many conflicting stories about him that I desired to hear his own account of himself. Rua did not so much as open the letter; it was quite enough that it was from the Native Minister. Becoming talkative, he assured me that he was willing to tell me anything I wished to know about himself, his people, and his plans. Yes, he would go with me to my hotel.

En route he stopped several times to speak with Maoris; and just before reaching the hotel he hailed a white man passing on a horse, and from a roll of bank bills which he drew from his pocket as he walked, he gave one note to the horseman. In spite of these interruptions, however, I eventually got him to my room. He was warm, and taking out a long pin, he removed his hat. To my astonishment, a big back comb was in his hair. It looked like part of an encircling crown.

With hands on his knees, Rua informed me that he would start at the beginning to give his history. "No use to start from the limbs of a tree and work down," said he emphatically. "I will start at the roots." The metaphorical tree proved to have tremendous roots; it could n't have been anything less than a Sequoia gigantea. Details were one of his specialties, and he all but went back to the days of Adam for some of them. He certainly submitted a good case for himself, and possibly he imagined I believed everything he told me.

"I was born," he began, "in 1868. At twelve years of age I began to ponder on the questions of life. I thought on the Maoris' future, and dwelt on their past. I saw that to do right man must live right; but though I thought much, I was not bold to speak my opinions, fearing the elders among my people would say, 'He is too young for that.'

"In 1906 I could see clearly. God's power came to me, and people who knew me as a boy recalled the sayings of my youth. Then these said, 'Rua talked sense in those days.' I saw there were two laws in the world—one, God's, the other, man's; the law that came from the Spirit, and the law that comes from man's mind. But it is God's law that should direct man. I talked to my people about this. I told them I was not taught in any school, but that my knowledge and inspiration came from God. God was my teacher. God's schooling is everything. He is in all knowledge.

"In 1908 I saw all the faults of the Maoris, and I had more of God's power in me then than in 1906. I was not afraid to say anything to anybody. I saw that the natives were dying out, because they were not using themselves rightly. I believed they should do something to improve their condition.

"I studied the land question. I saw there was little money in New Zealand, and that because of this the country was all the time borrowing. The reason was partly the tying up of so much land. Nobody was working it. If it were opened up for the pakeha, more money would come into the country. So I told the Maoris to sell some of their lands, but not for less than one pound an acre. My people have sold much land to the Government, and they will sell more."

I asked Rua if all the land-sale receipts were paid into his hands.

"No; every man gets his share," replied he. "I get my share and the other Maoris get their shares."

"Do you get a commission?" I suggested.

"No; all I have I earned working for the pakeha, and from my land. I have much land yet, also many cattle."

Detailing his plans for building a village at Waimana, Rua said he would spend $15,000 there in improvements. All this talk about possessions and town building was well enough for commercial history, but I wanted to know what the man's claims as a prophet were.

"There have been many prophets," he reminded me. "I am a general prophet. I know something of everything."

Could it be that Solomon reincarnated was before me! "Do you claim to be a second Christ, Rua?"

"Yes," he instantly assured me.

"Do you maintain that you have the same powers as Christ? Can you heal the sick?"

At the moment I asked these questions there came a knock at the door. A merchant with whom the prophet dealt extensively entered, and told him he was wanted at the wharf, at once. Freight had arrived, and only he knew where to store it. Rua left me with a promise to see me again at seven o'clock that evening, in the back room of that merchant's store.

Shortly after that hour he sauntered past the appointed place, with a wife on each side of him. One wore a sky-blue skirt and a black waist, the other had a pink gown with lace trimmings. Each woman had a gold chain necklace and enormous greenstone ornaments. Their husband seemed to have forgotten me, but at the hail of my interpreter he entered the store and resumed the interview.

Answering my last question, he said he was Christ's successor. I asked for his authority. That started him in earnest. Straightway he made for the roots of his figurative tree, and as he burrowed he waved his hands, pointed with fingers, and thumped his knees. There was no pause in his speech, and he proved to be a master of circumlocution.

I had told the interpreter it would not take me long to complete the interview, but I was not then acquainted with the Maori way of replying to questions. The Maoris are strong on genealogical history, and when opportunity is offered they delight to beat the entire range of their intellect in quest of material, which, when found, is instantly seized, whether closely or remotely related to the issue involved.

Rua was like the rest of his race. With his wives sitting near him he expounded the Scriptures like an old-time revivalist, with himself as the central figure. He talked until he perspired, yet he seemed to be getting farther from the end every minute. Like the Irish seaman's rope, the end appeared to be cut off. It was too much.

"Stop him!" I commanded the interpreter. "We shall be here all night if he is going to continue like this. Won't he answer 'yes' or 'no'?"

"No," replied he. "Rua wants to go far back to give you a good explanation of everything leading up to your questions."

I threw a switch to sidetrack the prophet, for I was feeling musty under this sprinkling of the dusty past. Did he have any rules of moral conduct for his followers? Only advisory, he told me. He had advised the Maoris neither to drink nor smoke, because such indulgence tended to decrease their numbers, but they had not accepted his counsel. Any other result, however, could scarcely have been expected,—at least with regard to drinking intoxicants,—for, I was informed, Rua could at that time "take a long beer with anybody."

As I had heard conflicting stories regarding the number of Rua's wives, I asked him for census returns. "Seven," came his reply. "And none of them is jealous."

I took a deep breath, gripped my chair, and stared at him. Wonderful man! I asked for the formula. It was brief: "My power keeps them from being jealous of each other."

Was not this the first instance of the kind the world had ever known? I asked this model bigamist. No, he modestly disclaimed, there was one other man equally distinguished. He also had seven unjealous wives, and he was an Old Testament prophet named Rameka. That was a Maori name for this seer, so I demanded an English translation. This was about the only point on which Rua apparently was ignorant.[1]

By this time Rua's two wives, who had been acting like bashful children, were so amused by the interview that they could scarcely control their risibility, and fain would have laughed. In truth, the proceedings were equal to a vaudeville sketch.

Rua confidently told me that God approved of his polygamy, but it would be wrong, he maintained, for other men to do likewise.

"It is right for me to have seven wives," declared he, "because the Bible say so. I have more wives than any other man because the law of the Almighty protects me from man's law. Man's law say only one wife. I take more to see if man's law reached me. The law did nothing. God protected me from the Government, and I know he means for me to have seven women."

"Would the Lord allow your followers to have more than one wife?" I finally asked him.

"No," he explained, "because they are not prophets."

To the pakeha Rua would concede nothing. God objected to the white man having more than one wife at a time. When I asked for further particulars, he immediately started on a return to the dawn of history. As it promised to be the dawn of morning before he reached current events again, I hastily fled to the gaslight glare of my hotel.

The next morning I saw him and one of his wives in a trap, bound for Waimana. Preceding them were two wagonettes of color; in these were his other wives.

Weeks later I learned that Rua had been fined five hundred dollars and costs for sly-grog selling in Waimana. As he pulled out a roll of notes representing from two thousand to five thousand dollars, he remarked: "I will see the Governor about this." Had Rua been moved to prophecy at that moment, probably he would have forecasted some dreadful calamity—at least an earthquake, or a tidal wave.

To dog the footsteps of the fanatical warrior-prophet Te Kooti forty years before would have been a risky venture. But one morning, with the cunning seer long in spirit land, with peace restored, and with Tom, the half-caste Opotiki constable, at my side, it was quite safe to go where the doughty Hauhau once had trod. We were bound for Waioaka, a former stronghold of Te Kooti's, and now a shiftless-looking spectacle at the base of foothills, seven miles from Opotiki. It was Saturday, the Hauhaus' Sabbath, and we hoped to reach the pa in time for church.

Many years ago, an old Maori told me, Waioaka was the largest of four pas that then stood in the immediate neighborhood, and had three thousand inhabitants. As Maoris are not noted for accuracy in furnishing census returns, that number of inhabitants probably was an exaggeration. Perhaps it included dogs and cattle; for the Maori loves a joke, and census enumerators not infrequently have learned that heads of native households have represented canines and livestock to be human beings, and they have been so entered. At any rate, the settlement's population was now little more than one hundred persons.

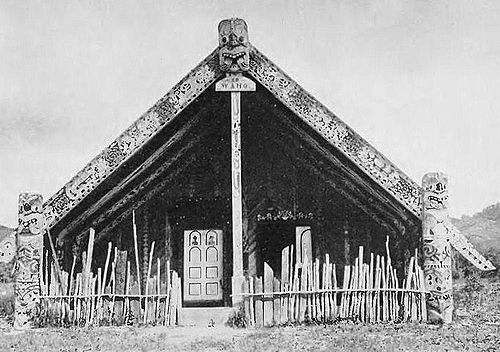

There was nothing formidable in Waioaka's appearance as we drew near it. Only low, grass-grown sections of the demolished ramparts remained. There were no ditches to cross, no closely-set tree-trunks to scale, to reach the group of small one-story houses built around the carved house of worship. Still there was a barrier, a sort of mongrel affair. It was a diversified fence, a fence in evolution. Tree-fern trunks tied with supplejack were succeeded by barbed wire, and that by smooth wire; then came a gate; not a carved portal with hostile form above it, but just a common pasture gate. It was opened to us by a Maori boy.

Scarcely anybody was about. "The people must be in church," said I.

"No, I don't think so," replied Tom. "If they were the church door would be open."

Near us stood a group of boys and girls with uncombed hair and loose-fitting clothes. Was it a Sunday-School class? No; these youths and maidens were merely waiting for dinner. As we drove toward the village square, an old man waved his hand to Tom, and came to meet us. He was clad in new overalls, a torn gray coat, and a vest; a cap crowned his head and unlaced shoes protected his feet. He shook hands with us. Following him came a large, barefooted man wearing a dark suit. Both were prominent men of Waioaka. Then we were called upon to shake hands with a woman in black. We accepted their invitation to sit down on the village green, and there told this volunteer entertainment committee why we had come.

Alas! we were too late. Church was dismissed. The benediction or its equivalent had been pronounced at 10.30, and there would not be another service that day until seven, and again on Monday. On Monday!

"Yes, and on every other day of the week, before breakfast and after supper," I was informed.

"But," explained a committeeman, "they don't all go to church every time. If they pray in their own homes, it is all right if they don't attend service. If they don't go to church or don't pray at home, they are not doing right."

A great many pray at home in Hauhau land, and on this day Waioaka could not be excepted. Where were the villagers? There were so few the place was lonely. Some had gone to town.

"But this is their Sunday," I said to Tom.

"Well," explained he, "they like to see what's going on in Opotiki. Even Mary Hira, the chief woman of Waioaka, has gone to town to-day."

We were late for church services, but could we not do the next best thing, and see the church's interior? Yes, said the man in overalls, as he turned to lead the way to the wharepuni, which stood inside a fenced area, and had a flower garden in front. At one corner hung a little bell. The building was old, with the exception of the roof, the outside carvings being decayed with age and dull with faded paint. Outside the inclosure was a meeting house of more modern appearance. Indeed, it was so modern that the carved figure at the front gable peak looked more like a Beau Brummel than a Maori warrior, although a mere held in one hand indicated warlike propensities.

Passing under two long gable boards bearing carved representations of three noted Maori ancestors coming to New Zealand astride a great fish, our village guide opened a large wooden sliding window and threw back the heavy sliding door. Just prior to this Tom warned me, "You must not take food, pipe, or matches into this house. To do so would be a desecration."

Suiting action to words, he placed his pipe and matches on the ground outside.

The wharepuni's interior was gloomy. It was a good place for solemnity. On the bare floor of the one large room there was not a single bench or chair. All around the room were carved wood panels, thick, and of various widths. Each of them, said my guide, represented a dead great man or woman. I wished to know why some panels were so much wider than others.

"Because," elucidated Tom, "some persons were greater than others."

So, after death, a Maori's greatness was measurable by the width of his memorial panel! Simplicity, like consistency, thou art a jewel! Why should not the memorial tablets of the Caucasian be modeled likewise?

Each panel bore a different design, and between the panels, likewise differing from each other in pattern, were combinations of strips of wood tied to toitoi with narrow strips of flax and the tough creeper kiekie. The wood and flax were dyed red and black, and the kiekie's bleach furnished white.

At the bases of the posts supporting the roof were carved figures. One was an incongruous production, being such a mixture of ancient and modern styles that one would be justified in presuming that the finishing touches were made by a humorous great-grandson of the artist who began it. The head was carved in ancient fashion, the face being elaborately tattooed. The remainder of the figure was painted, showing a black tie, a low black waistcoat, and black trousers and shoes. It looked as if the upper part had come from a Maori battlefield and the lower from a ballroom or a banquet hall of the twentieth century.

As it was with this carved and painted pedestal, so differences distinguish the Hauhaus of to-day from their warring forefathers. The Hauhau faith was established in 1864 at the base of Mount Egmont by the mild-mannered Te Ua. About the same time its believers started a war against the colonials, and for seven years their war-cry of "Father, Good and Gracious," accompanied by right-hand passes and the cry "hau," was heard from Taranaki to the Bay of Plenty. When they marched to battle a sacred party of twelve warriors preceded the army; and when in action bullets were rendered harmless, they professed to believe, by mystic hand and barking "hau." When a warrior fell, loss of faith was given as the cause. Chief of all the Hauhaus was Te Kooti. By his followers he was regarded as a demigod, and by the troopers, who were three years effecting his capture, he was admitted to be an accomplished Artful Dodger.

Not many religious sects, if any, are more tolerant than the Hauhaus of to-day. Where, for example, has there occurred an instance of one Caucasian religious denomination giving one of its important yearly meetings into the hands of widely differing believers? The Hauhaus have done so. A Mormon missionary told me TE KOOTI'S HOUSE

that he reached a Maori village soon after the Hauhaus had opened an annual conference. He entered the Hauhaus' wharepuni, and as soon as his presence was known the meeting was placed in his hands, and he conducted it two days. As soon as he was gone, the Hauhaus reconvened. After all, was this liberality undisguised politeness, or a disguised desire to get rid of the missionary in a diplomatic way?

Following our inspection of Waioaka's house of worship, Tom and I strolled about the village, entering smoke-stained kitchens, mat-carpeted sleeping-houses, and mouldy sweet potato pits. In the native-built houses warmth seemed to be the main consideration. That is why, looking into a sleeping-house large enough for two or three families, I saw that the interior resembled a smokehouse. The walls and ceiling were as brown as a cured side of bacon, and there was no apparent outlet for smoke excepting through open door and sliding window. When these were closed, the room was a capital place for coughs and inflamed eyes, as was many another Maori house of olden days, when a hole in the roof was commonly a substitute for a chimney. Some of the sleeping-houses of Waioaka contained mattresses, but the majority had only flax and kiekie mats, under which bulrush was sometimes spread.

Excepting one place, we were welcome in all parts of the village. The exception was the little cemetery on the hill. In their graveyards the Maoris do not, as a rule, want white visitors, I was told. Fear of desecration is given as one reason for this attitude; another reason is fear of the theft of ornaments from the bodies. If these are stolen, say superstitious natives, the spirit of one whose body is thus dishonored cannot abide in Heaven.

As we neared the close of our village sight-seeing an odor of cooking was wafted to us. Waioaka was preparing its noonday meal. Most of the cooking was done outdoors, in pots and on heated stones. When the stones were sufficiently heated by the fire built around them all the ashes and unconsumed wood were raked away, whereupon vegetables and meat or fish were placed on the stones, and over all water was poured. The whole was then covered with sacks, and in the smothered steam the food was soon and wholesomely cooked.

Unknown to me, I had been invited to dine while I was inspecting Waioaka. Tom told me about it after we had departed.

"I did n't accept the invitation for you," he laughingly explained. "I said, 'No, we will go home to dine.’ They were eating rotten corn. It had a terrible smell. It must have been in water twelve months."

Not often does one hear of a king in the rôle of a real estate agent. In Mahuta, third of Maori kings. New Zealand had such a potentate when I was in the Dominion. When he was not in his royal city of Waahi, beside the broad Waikato River, this king, since dead, was usually at the offices of Messrs. Mahuta and Kaihau, Queen Street, Auckland. About the first intimation Auckland had that there was a king in the ranks of its land and estate agents was a newspaper item detailing the flight of Mahuta's partner from a wrathful wahine, who vigorously scratched and kicked the big Maori Member of Parliament for alleged unfair dealings.

Desiring to see the monarch in his new character, I resolved to call on him. But first I went to the public library to read up on his majesty. I thought I should find all I required in "Who's Who in New Zealand." Diligently I searched between its red covers, but vainly. Other Maoris were recorded in this book of greatness, but of Mahuta, King of all the Waikatos, there was not one word!

I called on Messrs. Mahuta and Kaihau one afternoon. Through an open door I saw a Maori of large size seated in an equally ample leather-bottomed chair. It was Henare Kaihau, for fifteen years a Member of Parliament, so he told me. On the opposite side of his desk was a chair similar to his own, empty. Intuitively I felt that the King was out. He was, and would not return until the following morning. At the appointed hour I was there, but the King was still out.

"Gone home to-day," said Kaihau. "Won't be in till next week,"

That would not do, as I should not then be in Auckland. "I shall have to see Mahuta at his home," I told Kaihau.

"What you want to see him for?" asked he. "I can speak for him. Mahuta leave me to do the business. I am just the same as King. I can answer all your questions."

"Oh, you are the King's prime minister?"

"Just the same."

"What does Mahuta do?" I interrogated.

"He does nothing," came the astonishing reply. "He leave me to do the business here."

"The King is merely a drawing card, then?" I asked; but Kaihau evaded the query, or preferred not to view his association with Mahuta in that light.

"I have the King come here, and Maoris come here and see him. They ask him if they should do this or do that. The King may be say, 'Yes, do that,' and sends them to me. I do everything."

"How old is Mahuta; Mr. Kaihau?"

"Same age as me."

"How old are you?"

"About fifty-four."

"What is the name of the King's wife?"

"She has two names. You have a pencil? I show you."

Then the M.P. quaintly wrote:—

Nganeko Mahuta

Mara Mahuta

I was not satisfied with the interview, and I told the "prime minister" I intended to visit his royal partner at Waahi. Would I find any one in the royal household able to speak English? Yes, a woman.

The next day I took train for Huntly, a coal-mining town sixty-five miles south of Auckland, opposite to which the Maori sovereign dwelt. Crossing the Waikato River in a rowboat, and walking up its left bank three quarters of a mile, I reached the outskirts of Mahuta's capital. It looked like a village in a cornfield. Half encircling it were little patches of ripened maize, and high in willow trees that lined the river bank hung bunches of husked yellow corn. Near the corn sweet potatoes grew and pumpkins yellowed.

On a near approach no imposing architecture such as befits the resident city of a king was revealed. In what might well be termed a suburb of the village stood a Mormon church, the only European church in sight. Close at hand were small houses of wood and of wood and tree-fern trunks combined. Some of these huts brushed sides with large galvanized-iron chimneys; all were humble. Within the pa proper a tall, unpainted flagstaff cast a crooked shadow on a long carved meeting-house, which had on the apex of its front gable boards a wooden effigy with protruding tongue. Nearer the road stood a longer one-story building used as an eating-house at large meetings.

I looked for the village gate. I had thought I should find a carved door, perhaps with a wooden Colossus of ferocious mien bestride it. Instead I saw only a barbed-wire fence, which my eyes followed until they encountered a gap, such as one sees on a farm when bars are down. This was the village entrance. There was no barrier of any kind, nor any ornamentation.

Through the gap I saw fern-trunk fencing on one side of the village, and houses partly built of the same material. Most of the houses here were more substantial and respectable-looking than in the outskirts, and nearly all were on the right-hand side of the road, which corresponded to the main street.

As it was noon few of Waahi's inhabitants were astir. Some were squatting on floors eating, others were walking lazily about.

Hailing a Maori, I asked, "Where is Mahuta?"

"Somewhere up there," he answered carelessly.

In that vague precinct I paused at a picket fence surrounding a European cottage of more pretentious appearance than any other dwelling of the village. Under an awning raised on the front lawn a group of natives lay on mats and shawls. All were women excepting one, a contented-looking man. I surmised that I stood before Mahuta's "palace," and that this man was the King.

I made inquiry, but smiles of the "don't-understand" sort were the only responses. Where was that English-speaking woman Kaihau had told me I should find? I needed her badly now. Perhaps she was in that smiling group. At my query the man slightly inclined his head, but not enough to convince me that he intended to convey a meaning.

Feeling that I was leaving the King behind me, but determined to skirmish through the entire village in my quest, I continued up the "street." A youth vouchsafed me, "There his house," pointing to a small house

"KING" MAHUTA

adjoining the one I had just left. "He is not here," he added; "he is in Auckland."

"I was told he is here," I rejoined; and believing, from what Kaihau had told me, that the King had a native house, I asked the lad to point it out.

"Big house over there," said he.

The big house proved to be the meeting-house behind the crooked flagstaff. I now wondered if I were not being trifled with, Baffled and puzzled, and thinking the journey possibly would be fruitless, I was retracing my steps, when I saw a smiling man approaching me. He was well built and of medium size. His gray hair was closely cut, and he wore only a shirt, open at the throat, a black neckcloth, and a shawl, which served as a kilt. He was smoking a pipe. One hand held the shawl, the other was given me in greeting. I was in the strong grasp of the Waikato King, but it was a hospitable grasp.

I handed Mahuta a letter of introduction from the Native Minister, and he was nearly five minutes reading the two paragraphs, though they were typewritten in his own tongue. Supplementing it, I tried to engage Mahuta in conversation, and it was then I learned I had selected an unfortunate time for my visit.

"I have no time to-day," said the King. "My missus is sick. You see Kaihau in Auckland. He speak for me. What he say all right."

This was not encouraging, but finding that the King could speak more English than I had supposed, I did not want to leave him long enough to get an interpreter, fearing that if I did I should not get near him again. Telling him I had seen Kaihau, I asked, "How do you like the real estate business?"

His Majesty did not evade the question. It was plain he was not dodging the issue when he replied: "Me don't like it. Me rather be in Waahi. In Auckland too much tired. Too much walk around. Me like bed."

O ingenuous king!

Mahuta, I learned, was a popular ruler. "Do many people come to see you?" I asked him. Throwing up his hands, he replied: "Yes, many people. Sometimes big meetings in Waahi. Then all houses full and tents all around. Two thousand hundred men come."

As the King and I conversed, we were standing near a large fern-trunk building. To the immediate right was the village bell, hanging in a dead forked tree and overhung in turn by a cluster of corn. Toward this building the King moved, saying "Come have tea." Stepping across the threshold, we entered a large smoke-blackened room with a rough earth floor. In the centre a fire burned, and around it was a collection of pots and kettles. We were in the royal kitchen.

Four or five native women were present, some of whom were smoking pipes, and I observed a boy five or six years of age wearing only an undershirt. First giving the women some orders, Mahuta motioned me to follow him into a roughly boarded room at the other end of the building. This was the dining-room, furnished with ordinary tables, benches, and chairs. Here Mahuta tendered me an apology. "No meat," said he. Evidently it was not his customary lunch hour.

For his unexpected guest the King poured tea and cut thick slices of bread. Although Mahuta was reputed to be partial to strong drink, he was in a temperate mood this day. For him, as with Count Fosco on a plotting night, it was "the cold water with pleasure, a spoon, and the basin of sugar." He drank but one cup of cold, sweetened water. At the table Mahuta told me that one of his sons was a lawyer in Auckland, and his eager words and sparkling eyes proved that he was proud of his tama's achievement.

Rising at the close of the lunch, Mahuta, saying something I did not hear, crossed the road to the house that had been pointed out to me as his own. As the King mounted the steps several Maori youths were sitting on the veranda. These at once respectfully walked away. Through a window I saw my host searching a room. Presently he returned, holding an object in his hand. It was a piece of greenstone for me, a specimen that caused my ruddy, take-life-easy ferryman to ask, "What's your line?" when he saw the gift.

"Good-bye," said Mahuta, as he held out his hand to me. At the gate of his son's home he echoed my "Kia ora," and, trudging very slowly, went in to see his sick "missus."

THE END

- ↑ Asking the Anglican Bishop of Auckland to enlighten me on this question, I received the following explanation: "Rameka means Lamech, and as he is, in Biblical narrative, represented as the first bigamist, Rua, whose knowledge of Scripture, I am informed, was none too accurate, doubtless founded his deduction upon this somewhat precarious premise."