Popular Science Monthly/Volume 50/March 1897/The Racial Geography of Europe: Head Shape as a Racial Trait II

APPLETONS’

POPULAR SCIENCE

MONTHLY.

MARCH, 1897.

| THE RACIAL GEOGRAPHY OF EUROPE. |

A SOCIOLOGICAL STUDY.

(Lowell Institute Lectures 1896.)

By WILLIAM Z. RIPLEY, Ph. D.,

ASSISTANT PROFESSOR OF SOCIOLOGY, MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY; LECTURER IN ANTHROPO-GEOGRAPHY AT COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY.

II.—THE SHAPE OF THE HEAD AS A RACIAL TRAIT.

THE shape of the human head—by which we mean the general proportions of length, breadth, and height, irrespective of the "bumps" of the phrenologist—is one of the best available tests of race known. Its value is, at the same time, but imperfectly appreciated beyond the inner circle of professional anthropology. Yet it is so simple a phenomenon, both in principle and in practical application, that it may readily be of use to the traveler and the not too superficial observer of men. To be sure, widespread and constant peculiarities of head form are less noticeable in America, because of the extreme variability of our population, compounded as it is of all the races of Europe; but in the Old World the observant traveler may with a little attention often detect the racial affinity of a people by this means.

The form of the head is for all racial purposes best measured by what is technically known as the cephalic index. This is simply the breadth of the head above the ears expressed in percentage of its length from forehead to back. Assuming that this length is 100, the width is expressed as a fraction of it. As the head becomes proportionately broader—that is, more fully rounded, viewed from the top down—this cephalic index increases. When it rises above 80, the head is called brachycephalic; when it falls below 75, the term dolichocephalic is applied to it. indexes between 75 and 80 are characterized as mesocephalic. The two skulls in our illustrations, viewed from above, show how marked the differences in these proportions may be. In very rare instances the index may run in individuals as low as 62, and it has been observed as high as 103—that is to say, the head being broader than it is long. In our study, which is not of individuals, but of racial groups, the limits of variation are of course much

less. We shall seldom find heads in any considerable numbers exceeding the limits roughly indicated by the two crania in our illustrations.[1]

A factor which is of great assistance in the rapid identification of racial types is the correlation between the proportions of the head and the form of the face. In the majority of cases, particularly in Europe, a relatively broad head is accompanied by a rounded face, in which the breadth back of the cheek bones is considerable as compared with the height from forehead to chin. Anthropologists make use of this relation to measure the so-called facial index; but a lack of uniformity in the mode of taking measurements has so far prevented extended observations fit for exact comparison. It is sufficient for our purposes to adopt the rule, long head, oval face; short head and round face. Our six types on the next page, arranged in an ascending series of cephalic indices from 65 to 94, make clearly manifest this relation between the head and face. In proportion as the heads become broader back of the temples, the face appears relatively shorter. The correspondence is not exact, as, for example, in the case of the brachycephalic type from Piedmont in Italy, where the face is rather long for the breadth of the head. This is probably a case of individual variation, perhaps due to racial intermixture. Only a few examples of widespread disharmonism, as it is called, between head and face are known. The Greenland Eskimos resemble the Lapp shown in our portrait in squareness of face, notwithstanding the fact, illustrated in the world map on page 582, that they are almost the longest-headed race known. In Europe, where disharmonism is very infrequent among the living populations, its prevalence in the prehistoric Cro-Magnon race, will afford us a means of identification of this type wherever it persists to-day. At times disharmonism arises in mixed types the product of a cross between a broad and a long headed race, wherein the one element contributes the head form while the other persists rather in the facial proportions. Such combinations are apt to occur among the Swiss, lying as they do at the ethnic crossroads of the continent.

An important point to be noted in this connection is that this shape of the head seems to bear no direct relation to intellectual power or intelligence. Posterior development of the cranium does not imply a corresponding backwardness in culture. The broad-headed races of the earth may not as a whole be quite as deficient in civilization as some of the long heads, notably the Australians and Melanesians. On the other hand, the Chinese are conspicuously long-headed, surrounded by the barbarian brachycephalic Mongol hordes; and the Eskimos in many respects surpass the Indians in culture. Dozens of similar contrasts might be given. Europe offers the best refutation of the statement that the proportions of the head mean anything intellectually. The English, as our map of Europe will show, are distinctly long-headed. Measurements on the students at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology are fairly typical for the Anglo-Saxon peoples. Out of a total of 486 men, four were characterized at one extreme by an index below 70; the upper limit was marked by four men with an index of 87. The series of heads culminated at an index of 77, possessed by 72 students. This figure is near the average for the British Isles; and likewise, it should be added, for Hottentots and the wild men of Borneo, as our world map shows. Comparisons have been instituted in parts of Europe between the professional and uncultured classes in the same community. The differences in head form are as apt to fall one way as another, depending upon the degree of racial purity which exists in each class.[2] In our study of the proportions of the head, therefore, we are measuring merely race, and not intelligence in any sense. How fortunate this circumstance is for our purposes will appear in due time.

Basel, Teutonic Type. |

Berber, Tunis. |

Island of Ischia, Middle Italy. |

Equally unimportant to the anthropologist is the absolute size of the head. It is grievous to contemplate the waste of energy when, during our civil war, over one million soldiers had their heads measured in respect of this absolute size, in view of the fact that to-day anthropologists deny any considerable significance attaching to this characteristic. Popularly, a large head with beetling eyebrows suffices to establish a man's intellectual credit; but, like all other credit, it is entirely dependent upon what lies on deposit elsewhere. Neither size nor weight of the brain seems to be of importance. The long, narrow heads, as a rule, have a smaller capacity than those in which the breadth is considerable; but the exceptions are so common that they disprove the rule. Among the earliest men whose remains have been found in Europe, there was no appreciable difference from the present living populations. In many cases these prehistoric men even surpassed the present population in the size of the head. The peasant and the philosopher can not be distinguished in this respect. For the same reason the striking difference between the sexes, the head of the man being considerably larger than that of the woman, means nothing more than avoirdupois; or rather it seems merely to be correlated with the taller stature and more massive frame of the human male. Turning to the world map[3] on the next page, showing the geographical distribution of the several types

Lapp, Scandinavia. |

Piedmont, Northern Italy. |

Bavarian Tyrol. |

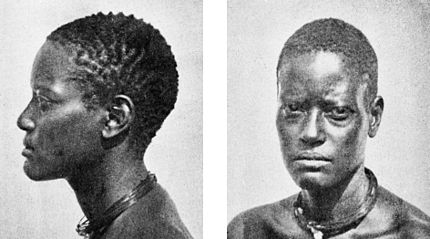

examples of these extremes. In profile the posterior development of the negro skull should be compared with the bullet-shaped head of the Asiatic. It will appear that differences in length are as remarkable as in the breadth. The line of division of head forms passes east and west just south of the great continental backbone extending from the Alps to the Himalayas. Thus the primitive natives of India, the black men of the hill tribes, who are quite distinct from the Hindu invaders, form part of this southern long-headed group. The three southern centers of long-headedness may once have been part of a single continent which occupied the basin of the Indian Ocean. From the peculiar geographical localization about this latter center of the lemurs, a species allied to the monkeys, together with certain other mammals, some naturalists have advocated the theory that such a continent once united Africa and Australia.[4] To this hypothetical land mass they have assigned the name Lemuria. It would be idle to discuss the theory in this place. Whether such a continent ever existed or not, the present geographical distribution of long-headedness points to a common derivation of the African, the Melanesian, and the Dravidian peoples of India. The phenomena of skin color and of hair only serve to strengthen the hypothesis.

The extremes in head form here presented between the north and the south of the eastern hemisphere constitute the mainstay of the theory that in these places we find the two primary elements of the human species. Other racial traits only help to confirm the deduction. The most sudden anthropo-geographical transition in the world is afforded by the Himalaya mountain ranges. Happily, we possess pretty detailed information for parts of this region, especially the Pamir. This "roof of the world" is of peculiar interest to us as the land to which Max Müller sought to trace the Aryan invaders of Europe by a study of the languages of that continent. It is clearly proved that this greatest mountain system in the world is at the same time the dividing line between the extreme types of mankind. It is really the

human equator of the earth. Such is as it should be; for while the greatest extremes of environment are offered between the steaming plains of the Ganges and the frigid deserts and steppes of the north, at the same time direct intercourse between the two regions has been rendered well-nigh impossible by the height of the mountain chain itself. In each region a peculiar type has developed without interference from the other. At either end of the Himalayas proper, where the geographical barriers become less formidable, and especially wherever we touch the sea, the extreme sharpness of the human contrasts fails. The Chinese manifest a tendency toward an intermediate type of head form.

Negro Type, Central Africa. Cephalic Index, 70±.

Japan shows it even more clearly. From China south the Asiatic broad-headedness becomes gradually attenuated among the Malays, until it either runs abruptly up against the Melanesian dolichocephalic group or else vanishes among the islanders of the Pacific. Evidence that in thus extending to the southeast the Malays have dispossessed or absorbed a more primitive population is afforded by the remnants of the negritos. These black people still exist in some purity in the inaccessible uplands of the large islands in Malaysia.

Compared with the extreme forms presented in the Old World, the Americas appear to be quite homogeneous and at the same time intermediate in type, especially if we except the Eskimo; for in the western hemisphere among the true Indians the extreme variations of head form are comprised between the cephalic indices of 85 in British Columbia and Peru, and of 76 on the southeast coast of Brazil. Probably nine tenths of the native tribes of America have average indices between 79 and 83. Many American peoples among whom customs of cranial deformation prevail are able artificially to raise their indices to 90 or even 95; but such monstrosities should be excluded for the present, since we are studying normal types of man alone. Translated into words, this means that the American Indians should all be classified together as, in a sense, a secondary race.

With them we may place the great group of men which inhabits the islands of the Pacific. These people manifest even clearer than do the American Indians that they are an intermediate type. They are, however, more unstable as a race, especially

Kalmuck Girl, Western Asia. Cephalic Index, 86.

lacking homogeneity. They seem to be compounded of the Asiatic and Melanesian primary racial elements in varying proportions. It is the most discouraging place in the world to measure types of head, because of their extreme variability. We shall have occasion shortly to compare certain of their characteristics other than the head form with those of the people of Europe. This we shall do in the attempt to discover whether these last are also a secondary race, or whether they are entitled to a different place in the human species. We shall then see that one can not study Europe quite by itself without gaining thereby an entirely false idea of its human history.

Before proceeding to discuss the place which Europe occupies in our racial series, it may be interesting to point out certain curious parallelisms between the geographical localization of the several types of head form and the natural distribution of the flora and fauna of the earth. Where, as in Africa and Australia, there is marked individuality in the lower forms of life, there is also to be found an extreme type of the human species. Where, on the other hand, realms, like the Oriental one which covers southeastern Asia and the Malay Archipelago, have drawn upon the north and the south alike for both their flora and fauna, several types of man have also immigrated and crossed with one another. Often the dividing lines between distinct realms for varieties of man, animal, and plant coincide quite exactly. The Sahara Desert, once a sea, and not the present Mediterranean, as we shall show, divides the true negro from the European, as it does the Ethiopian zoölogical and botanical realm from its neighbor. Thus the Berber of Tunis, on page 580, is properly placed in our series of European types. The Andes, the Rocky Mountains, and the Himalayas, divide types of all forms of life alike, including man. Even that remarkable line which Alfred Russel Wallace so vividly describes in Island Life, which divides the truly insular fauna and flora from those of the continent of Asia, is duplicated among men near by. The sharp division line for plants and animals between Bali and Lombok we have shown upon the map. It is but a short distance farther east, between Timor and Flores, where we suddenly pass from the broad-headed, straight-haired Asiatic Malay to the long-headed and frizzled Melanesian savage—to the group which includes the Papuans of New Guinea and the Australian.[5]

Following out this study of man in his natural migrations just as we study the lower animals, it can be shown that the differences in geographical localization between the human and other forms of life are merely of degree. The whole matter is reducible at bottom to terms of physical geography, producing areas of characterization. Where great changes in the environment occur, where oceans or mountain chains divide, or where river systems unite geographical areas, we discover corresponding effects upon the distribution of human as of other animal types. This is not because the environment has directly generated those peculiarities in each instance; certainly no such result can be shown in respect of the head form. It is because the several varieties of man or other mammals have been able to preserve their individuality through geographical isolation from intermixture, or contrariwise, as the case may be, have merged it in a conglomerate whole compounded of all immigrant types alike. In this sense man in his physical constitution is almost as much a creature of environment as the lower orders of life. Even in Europe he has not yet wholly cast off the leading strings of physical circumstance, as it is our purpose ultimately to show.

By this time it will have been observed that the differences in respect of the head form become strongly noticeable only when we compare the extremes of our racial series; in other words, that while the minor gradations may be real to the calipers and tape, they are not striking at first glance to the eye. As a matter of fact, it is the modesty of this physical trait—not forcing itself conspicuously upon the observer's notice as do differences in the color of the skin, the facial features, or the bodily stature—which forms the main basis of its claim to priority as a test of race. Were the head form as strikingly prominent as these other physical traits, it would tend to fall a prey to the modifying factor of artificial selection: that is to say, it would speedily become part and parcel among a people of a general ideal, either of racial beauty or of economic fitness, so that the selective choice thereby induced would soon modify the operation of purely natural causes. However strenuously the biologists may deny validity to this element of artificial selection among the lower animals, it certainly plays a large part in influencing sexual choice among primitive men and more subtly among us in civilization. Just as soon as a social group recognizes the possession of certain physical traits peculiar to itself—that is, as soon as it evolves what Prof. Giddings has aptly termed a "consciousness of kind"—its constant endeavor thenceforth is to afford the fullest expression to that ideal. Thus the nobility in Japan are as much lighter in weight and more slender in build than their lower classes as the Teutonic nobility of Great Britain is above the British average. The Japanese aristocracy in consequence might soon come to consider its bodily peculiarities as a sign of high birth. That it would thereafter love, choose, and marry—unconsciously perhaps, but no less effectively—in conformity with that idea is beyond per adventure.

Is there any doubt that where, as in our own Southern States, two races are socially divided from one another, the superior would do all in his power to eliminate any traces of physical similarity to the menial negroes? Might not the Roman nose, light hair and eyes, and all those prominent traits which distinguished the master from the slave, play an important part in constituting an ideal of beauty which would become highly effective in the course of time? So uncultured a people as the natives of Australia are pleased to term the Europeans, in derision, "tomahawk-noses," regarding our primary facial trait as absurd in its make-up. Even among them the "consciousness of kind" an not be denied as an important factor to be dealt with in the theory of the formation of races.

Such an artificial selection is peculiarly liable to play havoc with facial features, for which reason these latter are rendered quite unreliable for purposes of racial identification. And yet, because they are entirely superficial, they are first noted by the traveler and used as a basis of classification. A case in point is offered by the eastern Eskimos, who possess in marked degree not only the almond eye, so characteristic of the Mongolian peoples, but also the broad face, high cheek bones, and other features common among the people of Asia. Yet, notwithstanding this superficial resemblance, inspection of our world map of the head form shows that they stand at the farthest remove from the Asiatic type. They are even longer-headed than most of the African negroes. Equally erroneous is it to assume, because the Asiatic physiognomy is quite common among all the aborigines of the Americas, even to the tip of Cape Horn, that this constitutes a powerful argument for a derivation of the American Indian from the Asiatic stock. We shall have occasion to point out from time to time the occurrence of local facial types in various parts of Europe. On the principle we have indicated above, these are highly interesting as indications of a local sense of individuality, but they mean but little, so far as racial origin and derivation are concerned.

Happily for us, racial differences in head form are too slight to suggest any such social selection as has been suggested; moreover, they are generally concealed by the headdress, which assumes prominence in proportion as we return toward barbarism. Obviously, a Psyche knot or savage peruke suffices to conceal all slight natural differences of this kind; so that Nature is left free to follow her own bent without interference from man. The color of skin peculiar to a people may be heightened readily by the use of a little pigment. Such practices are not infrequent. To modify the shape of the cranium itself, even supposing any peculiarity were detected, is quite a different matter. It is far easier to rest content with a modification of the headdress, which may be rendered socially distinctive by the application of infinite pains and expense. It is well known that in many parts of the world the head is artificially deformed by compression during infancy. This was notably the case in the Americas. Such practices have obtained and prevail to-day in parts of Europe. For example, the people about Toulouse in the Pyrenees are accustomed to distort the head by the application of bandages during the formative period of life. This deformation[6] is sometimes so extreme as to equal the Flathead Indian monstrosities which have been so often described. Fortunately, these barbarous customs are rare among the civilized peoples which it is our province to discuss. Their absence, however, can not be ascribed to inability to modify the shape of the head; rather does it seem to be due to the lack of appreciation that any racial differences exist, which may be exaggerated for social effect or racial distinction.

Another equally important guarantee that the head form is primarily the expression of racial differences alone, lies in its immunity from all disturbance from physical environment. As will be shown subsequently, the color of the hair and eyes, and stature especially, are open to modification by local circumstances; so that racial peculiarities are often obscured or entirely reversed by them. On the other hand, the general proportions of the head seem to be uninfluenced either by climate, by food supply or economic status, or by habits of life; so that they stand as the clearest exponents which we possess of the permanent hereditary differences within the human species.[7] Ranke, of Munich, with Virchow, the leader of anthropological science in Germany, has long advocated a theory that there is some natural relation between broad-headedness and a mountainous habitat. He was led to this view by the remarkable Alpine localization, which we shall speedily point out, of the brachycephalic race of Europe. Our map of the world, with other culminations of this type in the Himalayan plateau of Asia, in the Rocky Mountains, and the Andes, may seem to corroborate this view. Nevertheless, all attempts to trace any connection in detail between the head form and the habitat have utterly failed. For this reason we need not stop to refute it by citing volumes of evidence to the contrary, as we might.[8] Our explanation for this peculiar geographical phenomenon, which ascribes it to a racial selective process alone, is fully competent to account for the fact. The environment is still a factor for us of great moment, but its action is merely indirect. In the present state of our knowledge, then, we seem to be justified in ruling out environment once and for all as a direct modifier of the shape of the head.

Having disposed of both artificial selection and environment as possible modifiers of the head form, nothing remains to be eliminated except the element of chance variation. This last is readily counterbalanced by taking so many observations that the fluctuations above and below the mean neutralize one another. Variation due to chance alone is no more liable to occur in the head than in any other part of the body. Rigid scientific methods are the only safeguard for providing against errors due to it. It is this necessity of making the basis of observation so broad that all error due to chance may be eliminated, which constitutes the main argument for the study of heads in the life rather than of skulls; for the limit to the number of measurements is determined by the perseverance and ingenuity of the observer alone, and not by the size of the museum collection or of the burial place. It should be added that our portraits have been especially chosen with a view to the elimination of chance. They will always, so far as possible, represent types and not individuals, in the desire to have them stand as illustrations and not merely pictures. This is a principle which is lamentably neglected in many books on anthropology; to lose sight of it is to prostitute science in the interest of popularity.

The most conspicuous feature of our map of cephalic index for western Europe[9] is that here within a limited area all the extremes of head form known to the human race are crowded together. In other words, the so-called white race of Europe is not physically a uniformly intermediate type in the proportions of the head between the brachycephalic Asiatics and the long-headed negroes of Africa. A few years ago it was believed that this was true. More recently, detailed research has revealed hitherto unsuspected limits of variation. In the high Alps of northwestern Italy are communes with an average index of 89, an extreme of round-headedness not equaled anywhere else in the world save in the Balkan Peninsula and in Asia Minor. A typical Italian from this district, chosen for me by Dr. Livi, of Rome, from among three regiments of recruits, is shown on page 581. In profile the back of the head is even less developed than that of the Kalmuck girl in our illustration. This type of head prevails all through the Alps, quite irrespective of political frontiers. These superficial boundaries are indicated in white lines upon the map to show their independence of racial limits. There is no essential difference in head form between the Bavarians and

the Italian Piedmontese, or between the French Savoyards and Tyrolese.

From what has been said, it will appear that these Alpine populations in purity exceed any known tribes of central Asia in the breadth of their heads. Yet within three hundred miles, as the crow flies, in the island of Corsica, are communes with an average cephalic index of 73. These mountaineers of inland Corsica are thus as long-headed as any tribe of Australians, the wood Veddahs of Ceylon, or any African negroes of which we have extended observations. A little way farther to the north there are other populations in Scotland, Ireland, and Scandinavia which are almost as widely different from the Alpine peoples in the proportions of the head as are the Corsicans. An example of extreme individual variation downward is shown in our illustrated Teutonic type, which has a lower index than any recorded for the longest-headed primitive races known. Nor is this all. Pass to northern Scandinavia, and we find among the Lapps again, one of the broadest-headed peoples of the earth, of a type shown in our series of portraits.

So remarkably sudden are these transitions that one is tempted at first to regard them as the result of chance. Further examination is needed to show that it must be due to law. Proof of this is offered by the map itself; for it indicates a uniform gradation of head form from several specific centers of distribution outward. Consider Italy, for example, where over three hundred thousand individuals, from every little hamlet, have been measured in detail. The transition from north to south is perfectly consistent. The people of the extreme south are like the Tunisian shown in our portrait; while at the knee of Italy, halfway up, the mean type in our series of illustrations stands between the two geographical extremes in its proper place. So it is all over the continent. Each detailed research is a check on its neighbor. There is no escape from the conclusion that we have to do with law.

Two distinct races of man, measured by the head form alone, are to be found within the confines of this little continent. One occupies the heart of western Europe as an outpost of the great racial type which covers all Asia and most of eastern Europe as well. The other, to which we as Anglo-Saxons owe allegiance, seems to hang upon the outskirts of Europe, intrenched in purity in the islands and peninsulas alone. Northern Africa, as we have already observed, is to be classed with these. Furthermore, this long-headed type appears to be aggregated about two distinct centers of distribution—in the north and south respectively. In the next paper we shall show that these two centers of long-headedness are again divided from one another in respect of both color of hair and eyes and stature. From the final combination of all these bodily characteristics we discover that in reality in Europe we have to do with three physical types and not two. Thus we reject at once that old classification in our geographies of all the peoples of Europe under a single title of the white, the Indo-Germanic, or Aryan race. Europe, instead of being a monotonous entity, is a most variegated patchwork of physical types. Each has a history of its own, to be worked out from a study of the living men. Upon the combination of these racial types in varying proportions one with another the superstructure of nationality has been raised.

Among other points illustrated by our map of Europe is the phenomenon paralleled in general zoölogy, that the extreme or pure type is generally to be found in regions of marked geographical individuality. Such areas of characterization occur, for example, in the Alpine valleys, in Corsica and Sardinia, somewhat less so in Spain, Italy, and Scandinavia. The British Isles, particularly Ireland, at least until the full development of the art of navigation, afforded also a good example of a similar area of characterization. Europe has always been remarkable among continents by reason of its "much-divided" geography. From Strabo to Montesquieu political geographers have called attention to the advantage which this subdivision has afforded to man. They have pointed to the smooth outlines of the African continent, for example, to its structural monotony, and to the lack of geographical protection enjoyed by its social and political groups. The principle which they invoked appears to hold true in respect of race as well as of politics. Africa is as uniform racially as Europe is heterogeneous.

Pure types physically are always to be found outside the great geographical meeting places. The latter, such as the garden of France, the valleys of the Po, the Rhine, and the Danube, have always been areas of conflict. Competition, the opposite of isolation, in these places is the rule, so that progress which depends upon the stress of rivalry has followed as a matter of course. There are places where too much of this healthy competition has completely broken the mould of nationality, as in Sicily, so ably pictured by the late Mr. Freeman. It is only within certain limits that struggle and conflict make for an advance forward or upward. Ethnically, however, this implies a variety of physical types in contact, from which by natural selection the one best fitted for survival may persist. This means ultimately the extinction of extreme types and the supersession of them by mediocrity. In other words, applying these principles to the present case, it implies the blending of the long and the narrow heads and the substitution of one of medium breadth. The same causes, then, which conduce socially and politically to progress have as an ethnic result mediocrity of type. The individuality of the single man is merged in that of the social group. In fine, contrast of race is swallowed up in nationality. This process has as yet only begun in western Europe. In the so-called upper classes it has proceeded far, as we shall see. We shall, in due course of time, have to trace social forces now at work which insure its further prosecution not only among the leaders of the people, but among the masses as well. The process will be completed in that far-distant day when the conception of common humanity shall replace the narrower one of nationality; then there will be perhaps not two varieties of head form in Europe, but a great common mean covering the whole continent. The turning of swords into plowshares will contribute greatly to this end. Modern industrial life with its incident migrations of population does more to upset racial purity than a hundred military campaigns or conquests. Did it not at the same time invoke commercial rivalries and build up national barriers against intercourse, we might hope to see this amalgamation completed in a conceivable time.

- ↑ Our data are drawn in the main not from the relative proportions of each type of head occurring within a given area, but from general averages made up by including all head forms alike. The more scientific method would be to give the relative proportions of each type of head; but that is impossible with the present data. It is a comforting circumstance, however, that the results drawn from the average approximate closely enough to those obtained in the other way for all general purposes. Oftentimes, for lack of data, it is impossible to employ the more scientific method for detailed analysis. Anthropologists distinguish between the relative proportions of the head measured over all the soft tissues, giving the cephalic index, and those taken from the skull divested of all its fleshy parts, in which latter case the relation of length to breadth is expressed by the so-called cranial index. Experience has shown that the cephalic generally exceeds the cranial index by two units, more or less. In other words, the living head is relatively broader than the cranium by about three per cent. This would fix our extreme indices on the living head at about 72 and 89 for averages.

- ↑ Dr. Livi finds that in northern Italy the professional classes are longer-headed than the peasants; in the south the opposite rule prevails. The explanation is that in each case the upper classes are nearer a mean type for the country, as a result of greater mobility and ethnic intermixture. This topic is discussed by the author in Publications of the American Statistical Association, vol v, p. 38 seq.

- ↑ This map is constructed primarily from data on living men, sufficient in amount to eliminate the effect of chance. Among a host of other authorities special mention should be made of Drs. Boas, on North America; Sören Hansen and Bessels, on the Eskimos; von den Stemen, Ten Kate, and Martin, on South America; Collignon, Berenger-Feraud, Deniker, and Laloy, on Africa; Sommier and Mantegazza, on northern, Chantre and Ujfalvy, on western Asia; Risley, on India; Lubbers, Ten Kate, and Maurel, on Indonesia and the western Pacific. For special details vide Balz, on Japan; Man, on the Audamans; and others. For Africa and Australia the results are certain but scattered through a number of less extended investigations. Then there is the more general work of Weisbach, Broca, Pruner Bey, and others. All these have been checked or supplemented by the large collections of observations on the cranium. A complete bibliography, as detailed as the one provided for Europe, will be published in due time. It will never cease to be a matter of regret that observers like Paulitschke, Ehrenreich, Hartmann, Fritsch, Finsch, the Sarasin brothers, Stanley, and others, offer no material for work of this kind. For the location of tribes we have used Gerland's Atlas für Volkerkunde. It is to be hoped that Dr. Boas's map for North America, now ready for publication, may not long be delayed.

- ↑ Ernst Haeckel, in his Anthropogenic, gives an interesting map with a restoration of this continent as a center of dispersion for mammals.

- ↑ A good ethnological map of this region is given in Fr. Ratzel's History of Mankind, i, p. 144.

- ↑ For a-full account of such deformation, vide L'Anthropologie, Paris, vol. iv, p. 11, seq. The illustrations of such deformation, of the processes employed, and of the effect upon the brain development, are worthy of note.

- ↑ For a curiously old-fashioned statement of the exact opposite of this view, see A. H. Keane's Ethnology, recently published by Macmillan, pp. 43 and 177. There is one custom which is effective. The peoples who use hard cradles or wooden pillows for infants' use are undoubtedly modified in head form by it. This is a disturbing factor in the Americas, and to some extent in parts of Europe.

- ↑ This theory is best stated in J. Ranke, Beiträge zur physischen Anthropologie der Bayern, Part I, chap. ii, p. 75 seq.

- ↑ Complete technical details by the author as to the mode of construction, with full references for each portion of the continent, will be found in L'Anthropologie, Paris, vol. vii, pp. 513 seq. Since the above map was drawn, certain minor changes have been made, in conformity with suggestions received from European experts. They all appear in the map in L'Anthropologie to which reference is here made; most of them were so unimportant for present purposes that this map was left unchanged. The only serious modification would be to make Silesia much darker, as I believe it to be less Teutonized than this map indicates.