Popular Science Monthly/Volume 62/March 1903/The Fossil Man of Lansing, Kansas

| THE FOSSIL MAN OF LANSING, KANSAS. |

By Professor S. W. WILLISTON,

UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO.

CLOSE by the mouth of a small but deep ravine opening into the valley of the Missouri River eighteen or nineteen miles northwest of Kansas City, and two and a half miles east of Lansing, Kansas, a farmer and his two sons, some two or three years ago, began the excavation of a cave to be used for the storage of their farm and dairy products. In the intervals of their more active farm work, this excavation was carried further into the side of the hill, until it had reached a length of nearly seventy feet. In February, 1902, a human skeleton was exhumed at the end of this cave or tunnel, but it excited no great surprise, since many fragments of bones had been found in the progress of their work. Fortunately, however, most of the bones were saved, though some were broken up and removed with the excavated material, from which not a few were recovered later. In the latter part of March, Mr. Michael Concannon, the elder son, took with him to Kansas City a fragment of one of the jaws and showed it to a reporter of one of the daily papers, by whom a brief account of the discovery was published.

This notice attracted the attention of Mr. M. C. Long, the curator of the Kansas City Museum, a gentleman who has long been interested in things archeological. Mr. Long immediately visited the place of the discovery in company with Mr. F. Butts, and secured such parts of the skeleton as had been saved. They recognized the importance of the discovery, and, from Mr. Long's description, a more extended account was widely published by the newspapers, with more or less embellishment, as that of a glacial man. On July 18, the present writer, in company with Mr. Long, made as thorough an examination of the place of the discovery and the accessible remains as was possible at the time, the results of which were briefly published in Science of August 1. In this paper he affirmed his belief in the post-glacial age of the remains, attributing their inhumation to a time when the Missouri River flowed at an elevation of forty to fifty feet above its present bed.

Very soon thereafter the subject received the attention of a number of eminent geologists and anthropologists, those most competent to express an opinion upon the age of the deposits in which the bones were found and the character of the remains, who thoroughly examined the excavation and the bones. Among these were Professors Winchell and Upham, of Minnesota, Haworth, of Kansas, Chamberlin and Salisbury, of Chicago, Calvin, of Iowa, and Drs. Dorsey, of Chicago, Holmes, of Washington, and Hrdlicka, of New York, all of whom agree upon the essential facts concerning the discovery and the genuineness of the remains themselves.

Sketch Map of the Lansing Site. a, Concannon dwelling and point of contact of limestone river bluff and recent bench. b, Entrance to cellar-tunnel. c, Inner end of tunnel where skeleton was found. d, Trench opened by Bureau of American Ethnology. e-e, Outcrop of limestone of floor of excavation.f, Entrance of rivulet to Missouri river flood-plain. g, Contact of limestone spur and bench remnant on north side. After Holmes.

Section of the Lansing Site showing Bluffs and River beyond, looking South. a, Concannon dwelling and point of contact of limestone river bluff and recent bench.b, Entrance to cellar-tunnel. c, Inner end of tunnel where skeleton was found. d, Trench opened by Bureau of American Ethnology. e-e, Outcrop of limestone in rivulet bed. f, Entrance of rivulet to Missouri river flood-plain s, Grade of steam bed. After Holmes.

While, however, the authenticity of the find has never been questioned, save by a Kansas City newspaper, the nature of the deposits in which the bones were found, and, in consequence thereof, the age of the bones themselves has been the subject of not a little discussion, and of wide differences of opinion. Already the literature of the subject is considerable, and the reader who chooses may find it in the discussions by Professors Winchell and Upham, in Science and the American Geologist, by Professor Chamberlin, in the Journal of Geology, and, more recently, by Dr. Holmes, in the American Anthropologist. The subject, too, has been fully discussed at the Congress of Americanists in New York, and at the various meetings in Washington during the session of the American Association for the Advancement of Science. It is fortunate that the conditions were such that there can be no

View looking Northward across the Mouth of the Tributary Valley. showing Concannon's house at the left and the truncated slope under it, the mouth of the valley just beyond, and in the center the north bluff with its truncated face overlooking the Missouri bottoms, on the edge of which the railroad lies. The bluff is about 160 feet high. From a photograph by Mr. Chamberlin.

serious doubt concerning either the discovery itself or the nature of the remains. The small ravine, near the mouth of which the bones were discovered, opens upon the flood-plain of the Missouri River from the west. The ravine is less than a mile in length, with a fall of more than one hundred feet, and has no running stream, save perhaps for a short time in wet weather. Very near its mouth it has a tributary branch, perhaps a quarter of a mile in length, coming from the south, nearly parallel with the river bank. It is at the extremity of the intervening spur that the excavation was made, beginning a few feet above the bed of the ravine and extending southward nearly horizontally for a distance of seventy feet. The cave itself has for its floor in its whole length, a thick, nearly horizontal stratum of carboniferous limestone, but the material excavated is believed, in most part at least, to have been deposited by either the river or the recurrent freshets in the tributary ravine. The excavation has a width of about ten feet, and a height of seven or eight, the roof being slightly arched, which, with the walls, have retained their shape without support. Upon the floor, for a thickness of one or two, or in some places perhaps more, feet, there are many broken pieces of limestone, and shales, for the most part worn and disintegrated, that were evidently the talus from the adjacent hillside of carboniferous rocks. With these, however, and sometimes at higher altitudes there are not a few larger masses of

sharp-angled limestone masses, lying horizontally. In this talus material a number of fragments of water shells were found. About three feet above the floor, on the west side of the tunnel, and extending nearly horizontally inward, there is a stratified layer of finer material. At places this stratum is pinched out and scarcely distinguishable, and later excavations show that it does not extend further than the end of the tunnel as first excavated.

Its material is not unlike that of the walls of the tunnel elsewhere, though less coarse. Above this stratum, evidences of water stratification are indistinct or wanting. In some places there are whitish horizontal streaks of limited extent, and some observers believe that distinct indications of stratification are shown in the disposition of the occasional masses or small nodules of limestone and pebbles. However that may be, there are not a few fragments of worn limestone and

occasional pebbles, for the most part of local origin. Otherwise the material of the walls and roof everywhere is a fine, siliceous, sharp angled silt, firm and lumpy when dry, but a soft mud when wet. It contains some, but not much, carbonate of lime disseminated through it, and is of a yellowish brownish color. At the edge of the roof, near the outer extremity of the tunnel, the writer dug from the wall a complete cast of a river clam. The original shell had entirely disappeared,

leaving, however, the external markings sharp and clear. No other similar specimen has been discovered in the later excavations. Land shells, of three or four species, are abundant everywhere in the material. Fragments of bones of other animals than man have been discovered in the excavation, but they are indecisive in character,—a part of a bison vertebra, a mere fragment of a small artiodactyl metapodial, etc.

Additional excavations at the end of the tunnel, and a cross-section, undertaken at the instigation of Mr. Holmes, have disclosed the projecting point of carboniferous shales underlying the superincumbent drift material, between the end of the tunnel and the near-by bank of the river. Above the skeleton, the thickness of this silty material is about twenty feet, and the elevation of the terrace or knoll, between the tunnel and river bank, is about ten feet greater.

The present course of the Missouri River is at the opposite side of the flood plain a mile or more distant. Until within a few years, however, the river flowed within a few hundred yards of the entrance of the cave. In 1881, the year of the highest water known in the river at this place since 18-14, the water reached to within about seventy-five feet of the cave entrance, and to within twelve and a half feet of the

horizon of the skeleton, as determined from Mr. Martin Concannon's testimony.

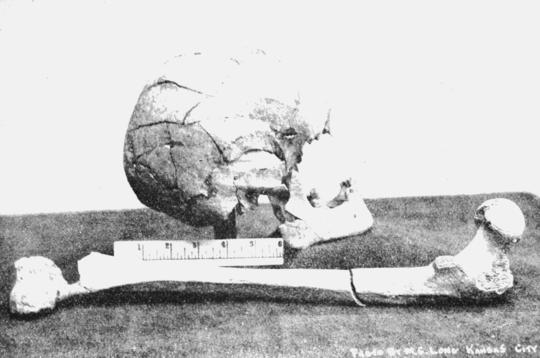

The bones discovered in the excavation belong to two different skeletons. One of these skeletons is represented by a single bone, the left upper maxilla, belonging to a child about nine years of age, as determined by the teeth, of which the permanent incisors and first molar were fully erupted, while the deciduous molars were much worn. This bone was found about sixty feet from the entrance of the cave, nearly upon the floor of the tunnel. The other skeleton was evidently complete, or nearly so, and but little disturbed. It was found about ten feet further away from the entrance, lying upon the limestone talus, though wholly covered by the silty material characteristic of the tunnel throughout. This skeleton is that of an adult between forty and fifty years of age, about five feet two inches in height, of slight build and, in much probability, of a female. The bones were firm, and as fully fossilized as could be expected in such material as enclosed them. The bones show in places an incrustation of a stony matrix commonly observed about bones of pleistocene animals preserved in river deposits in the west. I may also add that some of the bones of the leg show pathological deposits, probably rheumatoid. The young man who exhumed the skeleton stated that it was irregularly placed. As the specimen came under my observation it was largely enclosed in its original matrix. Very clearly it had not been covered by the limestone talus upon the floor of the cave. Portions of the encrusting matrix enabled one to determine that the bones had been in large part, if not wholly, articulated when discovered. Every collector of vertebrate fossils knows how rarely so large a skeleton as that of a man is found preserved entire and with the bones in position. The right femur was lying in its socket, but reversed; the left femur had been partly dislocated from its acetabulum, and was lying obliquely across the pelvis. Various other bones showed connections, and some of the bones of the feet are still united. Altogether, sufficient fragments were recovered to show that nearly every bone in the skeleton had been present. The femur measures a little more than seventeen inches in length (430 mm.), the tibia fourteen inches (350 mm.), the humerus twelve inches (302 mm.), the radius ten inches (250 mm.), and the forearm, from olecranon to wrist, eleven inches (277 mm.).

It seems very probable that the skeleton had been immersed in water while yet held together by the flesh. It is impossible that it could have been subjected to strong currents of water after the decomposition of the ligaments had occurred, nor could it have been exposed to the atmosphere for any length of time, nor even for a short time to the depredations of predatory animals while yet enclosed in the flesh. In other words, it seems almost beyond dispute that the person had either been thrown into the water very soon after death, or had been drowned, and that the body had remained immersed in comparatively quiet water until covered so deeply by the soil that it could no longer suffer the vicissitudes of exposure to the atmosphere and predatory animals. Evidences of artificial or accidental burial beneath the silt are wanting and are improbable. So far as any theory of the age of the skeleton is contradictory to this evidence it may be rejected.

Two chief views as to the age of the remains are now held: the one by Professors Winchell and Upham; the other by Professor Chamberlin, with the assent of Professors Salisbury and Calvin. To give all the reasons upon which these views are based is to repeat the already voluminous discussion, and we must content ourselves with the conclusions only.

According to Professors Winchell and Upham, the material covering the skeletons was deposited during the time of the fourth recrudescence or southward extension of the glaciers in the United States, in that stage known as the Iowan, that is, during the next to the last glacial extension which reached as far south as central Iowa. Under

View from the West showing Intersecting Trench dug to join the Original Tunnel, with the Concannon residence in background. The skeleton was found nearly below the place indicated by the larger light spot at the right of the trees. From a photograph by Professor Chamberlin.

this view, the valley of the Missouri River was at this time filled to a depth of a hundred feet or more, but has since been excavated to its present level, and the material covering the Lansing skeleton is a part which has not since been carried away. In support of this view, it is claimed that the material covering the skeleton is of the character of glacial loess; that it shows evidence of water stratification; and that there is no evidence to prove that there has been any subsidence of the valley subsequent to glacial time.

The other view is that presented by Professor Chamberlin. He believes that the inhumation of the remains dates from a time when the river bed was from fifteen to twenty-five feet above its present level, that is, when the waters of the river eroded the surface of the limestone upon which the bones were lying, and that the bones themselves were covered by the action of the river, or by the wash from the adjacent uplands. The material above the stratum already described, Professor Chamberlin believes to be without evidence of water stratification; that it was built up chiefly by the action of the tributary, which deposited its washed down silt from the uplands upon the comparatively low gradient of the end of its valley, while the river itself was flowing at the opposite side of its flood-plain. He admits as possible, though less probable, that the whole of the material covering the skeleton may have been deposited by the action of the river while flowing at a high elevation. Whether his views are finally accepted or not, they are supported by valid arguments, and are conservative. By this explanation a considerable antiquity is accorded to our Lansing man, but one far short of the glacial times. If the other explanation is accepted, the one first offered by the present writer, and the one suggested as possible by Professor Chamberlin, the age of the skeleton would be considerably greater, though still much short of the glacial times.

Yet another opinion is held by certain able geologists—that the whole of the material covering the skeleton, and to the top of the knoll, full forty feet above the flood-plain, has been built up, for the most part at least, by the action of the tributary. This explanation might permit the inhumation of the skeleton within very recent times, since the settlement of the valley by white men, indeed. But, this view seems incompatible, not only with the physical conditions presented, but also with the evidence afforded by the skeleton itself, and is, I believe, untenable. This explanation would require the covering of the skeleton while yet in the flesh, by some sudden freshet in the ravine, so deeply as to be beyond the effects of the atmosphere, and the reach of the many prowling wolves and other predatory animals— a requirement that seems quite improbable, considering the position and condition of the skeleton. Such a freshet would be far more likely to wash the body or skeleton far out into the valley of the river.

Dr. Holmes has somewhat modified Professor Chamberlin's views, in that he believes that a change of level in the altitude of the river of five or ten feet would be sufficient to have met the conditions presented. However, Mr. Holmes frankly says that the decision must finally rest with the glacial geologists, none of whom has so far published anything to sustain the lessened estimate. Furthermore, Mr. Holmes' views are open to the same objections as those just given. It seems to me that nothing short of Professor Chamberlin's estimate will meet the paleontological requirements.

As to the character of the remains themselves, both Dr. Hrdlicka and Dr. Dorsey, to whom may confidently be left the final decision, assert that they are of modern type, and might well belong to an Indian inhabiting the plains region within quite recent times, so far as anthropological evidence goes. Nor does this verdict as to the character of the remains have much to do with either of the views presented. It is certainly not improbable that the widespread races of American Indians date back for thousands of years in their history. Mr. Upham's estimate of the time since the death of the Lansing man is about twelve thousand years, a not unreasonable time for the evolution of the American Indian.

Evidences of the high antiquity of man in America have hitherto been wanting, or doubtful, and the Lansing man, whichever age is assigned to him, can claim but little greater age than might be given him from à priori reasoning. One must frankly admit that proofs of man's contemporaneity with the many extinct animals of the pleistocene times in North America have been few, and perhaps in some cases doubtful. But, that man has existed with some of the large extinct animals of North America, the present writer, in company with other vertebrate paleontologists, believes. But this belief does not carry with it, necessarily, a belief in any very great antiquity. It seems very probable that some of these large animals, such as the elephant, mastodon and certain species of bison, have lived on this continent within comparatively recent times.

Furthermore, if the evidences of the commingling of human and extinct animal remains in South America are to be accepted, and such evidences seem almost beyond dispute, it must necessarily follow that man has existed on our own continent for a yet longer time, since there could have been no other way for him to reach the southern continent than through the Isthmus of Panama. In additional support of the evidence of man's high antiquity in South America, I am permitted to quote the following from a recent letter by Professor W. B. Scott, the distinguished paleontologist of Princeton University, who has recently spent some time in those regions in the study of the extinct vertebrate fauna: "I am convinced, from personal examination, that man existed in South America contemporaneously with the great, extinct mammals. To be more explicit, human remains have been found in the Pampean beds in association with large numbers of extinct mammalian genera." Is it not reasonable to suppose that we must seek for the earliest indications of man's habitation on our continent in the Pacific regions?