Popular Science Monthly/Volume 64/April 1904/The Progress of Science

THE CENTENARY OF THE DEATH OF PRIESTLEY.

Priestley died on February 6, 1804, and the centenary of his death has been commemorated in Great Britain and in the United States. Thirty years ago the centenary of the discovery of oxygen was celebrated, and at that time this magazine published several articles on the life and work of Priestley. In the issue for August, 1874, a biographical sketch and an appreciation by Dr. John W. Draper will be found. An address given by Huxley on the occasion

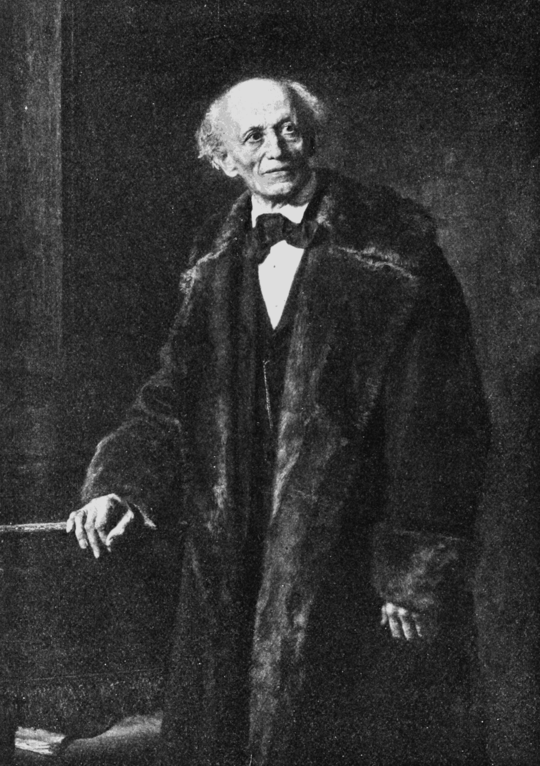

Professor Eduard Zeller.

of the presentation of a statue of Priestley to the town of Birmingham is printed in the issue for November, 1874. Priestley's own account of the discovery of oxygen was reprinted in the issue for December, 1900. To these articles those readers may be referred whose attention has been attracted to Priestley by the recent commemoration.

Priestley's discoveries were of epoch-making importance in the history of chemistry; his radical views in politics and theology anticipated in certain directions the course of subsequent thought, and his career is full of dramatic interest, especially to us in America, among whom he took refuge from persecutions at home. Yet it is not often that one of the twenty-five volumes containing Priestley's collected works is taken down from the shelves of the library. The vast range of his controversial writings belongs to the past, and his scientific work was in a sense an episode in his life and in the development of science. But the courage with which he defended what was then heterodoxy in religion and radicalism in political affairs deserves our admiration, and the discovery of oxygen will always remain a landmark in the progress of chemistry.

At the middle of the seventeenth century, chemistry had not yet found its Copernicus or Newton. From our point of view the confusion was extreme. Air, water and fire were regarded as elementary substances. It was supposed that when anything was burned or when an animal breathed, a substance called phlogiston passed into the air and vitiated it. So when Priestley discovered oxygen, he called it dephlogisticated air, it being, 'between five or six times as good as common air.' Priestley did other work of importance in connection with gases, but did not appreciate the real bearings of his own discoveries and can not be placed in the same rank with Cavendish and Laviosier. But he will always be remembered for one of the most important discoveries in the history of science.

PROFESSOR EDUARD ZELLER.

It appears that in Germany, as in England, the great men of the nineteenth century have scarcely bequeathed their genius to their successors. It is quite impossible for Berlin to fill the places vacant by the deaths of Helmholtz, Virchow and Mommsen. One man of that generation the university still has, and it does well to do him honor on his ninetieth birthday. Professor Zeller does not rank with the greatest of his contemporaries, but he represents the highest scholarship, the type which is in danger of submergence beneath the flood of executive work and business detail of modern life.

The work of Professor Zeller carries us a long way back. Starting from the then prevalent Hegelianism, he was one of the first to take a decided stand against the à priori construction of the world, and claim that we must go back to the epistemology of Kant and develop it in the light of modern science. But he is best known for his 'Philosophy of the Greeks,' the first volume of which was published sixty years ago. This work has continually been revised for subsequent editions; it was followed in 1872 by a history of German philosophy since Leibnitz and by numerous other publications, especially on the relation of philosophy to science and on the philosophy of religion.

CHARLES EMERSON BEECHER.

Yale University lost only five years ago its eminent paleontologist. Professor O. C. Marsh, and now we are compelled to record the untimely death of his successor. Professor C. E. Beecher, which occurred on February 14, at the age of forty-eight years. Beecher was graduated from the University of Michigan in 1878, and for ten years was assistant to Professor James Hall in the New York Geological Survey. In 1888 he was called to Yale University to take charge of the invertebrate fossils of the Peabody Museum, and received the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in 1889. In 1892 he was made assistant professor and in 1897 professor of historical geology, the title being changed to professor of paleontology in 1902. In 1899 he was elected a member of the National Academy of Sciences. In this year, when he succeeded Professor Marsh as curator of the geological collections, he presented to the museum his collection of fossils, which he had been gathering since he was twelve years old and which contained over 100,000 specimens.

Beecher published about sixty papers on invertebrate paleontology, concerned especially with brachiopods and trilobites. He obtained specimens of the latter in which the antennæ and legs were preserved, and made careful studies of the ventral anatomy. He also published a classification of the trilobites, and was at work on an extensive treatise on these primitive crustaceans at the time of his death. Beecher did much work in the field and was skilful in preparing specimens and as a draughtsman. He was also interested in the philosophical aspects of evolution, being counted among the American neo-Lamarckians. In an important paper he finds that species having spines fully developed leave no descendants.

SCIENCE AT COLORADO COLLEGE.

The state universities of the central and western states have developed with remarkable rapidity, and are now beginning to rival the older institutions of the Atlantic seaboard. It is sometimes said that public support of education interferes with private endowments. But Stanford University and the University of Chicago have been established side by side with the state institutions, and in each case both the state and the private institutions are found to help rather than to interfere with one another. In Colorado in the same way the state university has not in any way prevented the development of Colorado College, and there is every reason to suppose that these institutions will continue to work togther for the educational welfare of the state. In all western institutions, science occupies an important if not a predominant position, and of this the erection of Palmer Hall at Colorado College is significant.

This new building, which was dedicated on February 23, contains provision for the scientific departments and administrative offices of the college. It has received its name in honor of General William J. Palmer, one of the trustees of the institution. As shown in the illustration, the building has three stories; it is built of

sandstone with modern fireproof construction. The basement contains laboratories for chemistry, physics and psychology, the first floor, the general offices and lecture rooms and other laboratories for chemistry and physics, and the second floor houses the departments of biology and geology, with the museum.

Nearly ten years ago Dr. D. K. Pearson, to whom American colleges are so greatly indebted, off"ered to give $50,000 to Colorado College, on condition that a building costing $60,000 should be erected. This money was secured and the building planned, but subsequently larger plans were adopted, and the present building cost nearly $300,000; $30,000 have also been secured for equipment. The dedicatory exercises were carefully planned. President David Starr Jordan, of Stanford University, made the principal address, which we hope to have the privilege of publishing in this magazine. On the preceding day addresses were made by Dr. C. R. Van Hise, president of the University of Wisconsin, on 'Colorado as a field for scientific research'; by Dr. Samuel L. Bigelow, of the University of Michigan, on 'The growth and function of the modern laboratory'; by Dr. C. E. Bessey, of the University of Nebraska, on 'The possibilities of the botanical laboratory,' and by Dr. Henry Crew, of Northwestern University, on 'Recent advances in the teaching of physics.' The president of the college. Dr. William F. Slocum, said in his address: "We dedicate then to-day this building devoted to the high purposes which led to the founding of the college; to the cause of learning and scientific study, to the up-building of the educational movement throughout the state. It is an added contribution to what other similar institutions are accomplishing in Colorado and throughout our country. In all the years to come may it help to broaden and enlarge the scope of human knowledge and aid in bringing into this section of the United States such a love of the larger life of thought and accurate study, and that new meaning will come to many as they read over its entrance, 'Ye shall know the truth and the truth shall make you free.'"

THE SIZE OF FAMILIES OF COLLEGE GRADUATES.

The statistics on the size of families of college graduates published last year in this magazine by Professor Thorndike and by Dr. Engelmann have been considerably amplified by President Stanley Hall and Mr. Theodate L. Smith, and form the subject of an article in the last number of The Pedagogical Seminary. It is pointed out that the decrease in the number of children per wife is less than per man, owing to the fact that the graduates of the last century so frequently remarried. The conditions for the wives of clergymen in colonial times appear to have been unfortunate, about forty per cent, dying under the age of fifty.

But the authors are scarcely justified in saying that 'on this biological blunder of estimating the increase of population per man instead of per woman and too narrow a study of statistics is based much of the alarmist outcry in regard to the future population of the United States.' As far as the increase of the population is concerned, it matters but little whether it is due to strict monogamy or to successive polygamy.

The figures given in the paper are substantially those with which we are familiar. The size of family of the married college graduate has decreased from about four in the first part of the last century to about two and a half in the second half, and at the same time the percentage of those unmarried has increased. Great care must, however, be taken in interpreting such statistics. For example, the members of the class of 1883 of Yale College are reported to have only five living children; but we find that the report relates to a period three years after graduation. Even when the period is as long as fifteen years the number of children will increase by about 50 per cent. The ominous fact stands, however, that college graduates do not now reproduce themselves. If the figures for Harvard College are correct, they are exterminated with startling rapidity, a hundred graduates produce only 68 boys in the next generation, and leave only 30 great-grandsons. It must, however, be remembered that the conditions in the race and class from which graduates come may be as bad. Thus the number of children living for every native Massachusetts woman, between the ages of forty and fifty, was, in 1885, only 1.80.

The statistics for the women graduates are of special interest, although they in most cases relate to such recent classes that they are difficult to interpret. They are also reported by diverse methods and are probably not very accurate. Thus when it is said that of 176 children only 11 have died, we infer that the deaths have not been reported rather than that the death rate is remarkably low. The only group fifty years of age consists of the first ten classes of Vassar College ending in 1876 with 323 graduates. Fifty-five per cent, had been married as compared with 80 per cent, in the native population, of whom about one third were barren, about twice as many as under normal conditions. The average fertility of those having children is three (including presumably those deceased), which is fully as large as that of the male graduates. The data from later classes are difficult to use. 42.7 per cent, of Smith College graduates prior to 1888 are married and 46.5 per cent, of the Wellesley College graduates. These women are of the average age of over forty years. If only one half of college alumnæ marry and one third of these are barren, while those who have children only reproduce themselves, the 'species' would be completely exterminated in five generations. If colleges for women must be regarded as modern nunneries, there is no special cause for gratification in the fact that in twelve years the number of women students has increased from about 10,000 to about 28,000.

THE STUDY OF THE SCIENCES AND OF LATIN IN THE SECONDARY SCHOOLS.

There is annually published in the report of the United States Commissioner of Education an interesting table showing among other things the percentages of students pursuing different studies. The table from the last volume referring to the year 1902 is here reproduced.

It will be noted that the percentage of students studying Latin is recorded as increasing from 38.80 in 1891-92 to 49.52 in 1901-2, whereas in physics there has been a decrease in the same period from 22.04 to 17.39 per cent., and in chemistry from 10.08 to 7.70 per cent. These figures have been widely quoted, and are certainly discouraging to those who are interested in scientific education. It must, however, be remembered that figures are illusive. It has been said that there are three kinds of lies—white lies, black lies and statistics. The figures given in the table are on their face difficult to

| Students and Studies. | 1891-92 | 1892-93 | 1893-94 | 1894-95 | 1895-96 | 1896-97 | 1897-98 | 1898-99 | 1899-00 | 1900-1 | 1901-2 |

| Males | 44.01 | 43.62 | 43.39 | 43.00 | 43.40 | 43.84 | 43.50 | 42.93 | 43.16 | 42.83 | 42.49 |

| Females. | 55.99 | 56.38 | 36.61 | 57.00 | 56.60 | 56.16 | 56.50 | 57.07 | 56.84 | 57.17 | 57.51 |

| Preparing for college, classical course | 9.18 | 9.90 | 10.34 | 10.00 | 10.05 | 8.94 | 7.99 | 7.87 | 8.32 | 8.30 | 6.89 |

| Preparing for college, scientific courses | 7.59 | 8.22 | 7.33 | 7.11 | 7.16 | 6.57 | 6.03 | 6.18 | 6.21 | 6.54 | 5.97 |

| Total preparing for college | 16.77 | 18.12 | 17.67 | 17.11 | 17.21 | 15.51 | 14.02 | 14.05 | 14.53 | 14.84 | 12.86 |

| Graduates | 10.87 | 11.46 | 11.88 | 11.60 | 11.73 | 11.95 | 11.75 | 11.78 | 11.74 | 11.95 | 11.86 |

| Per cent, of graduates prepared for college | 39.15 | 36.62 | 30.92 | 32.44 | 32.69 | 32.60 | 30.60 | 31.61 | 32.95 | 33.48 | 33.67 |

| Studying— | |||||||||||

| Latin | 38.80 | 41.94 | 43.59 | 43.76 | 46.22 | 48.01 | 49.44 | 40.29 | 49.97 | 49.93 | 49.52 |

| Greek | 4.68 | 4.92 | 4.99 | 4.73 | 4.58 | 4.60 | 4.50 | 4.27 | 3.95 | 3.58 | 3.36 |

| French | 8.59 | 9.94 | 10.31 | 9.77 | 10.13 | 9.98 | 10.48 | 10.68 | 10.43 | 10.75 | 11.13 |

| German | 11.61 | 13.00 | 12.78 | 12.58 | 13.20 | 13.76 | 14.24 | 14.91 | 15.06 | 16.09 | 16.94 |

| Algebra | 47.65 | 49.92 | 52.71 | 52.40 | 53.46 | 54.22 | 55.29 | 56.21 | 55.08 | 55.66 | 55.27 |

| Geometry | 22.52 | 24.36 | 25.25 | 24.51 | 25.71 | 26.24 | 26.59 | 27.36 | 26.75 | 27.26 | 27.56 |

| Trigonometry | 2.96 | 3.61 | 3.80 | 3.25 | 3.15 | 3.08 | 2.83 | 2.58 | 2.42 | 2.54 | 2.42 |

| Astronomy | ........ | ........ | ........ | 5.27 | 5.19 | 4.89 | 4.40 | 3.94 | 3.43 | 2.96 | 2.64 |

| Physics | 22.04 | 22.25 | 24.02 | 22.15 | 21.85 | 20.89 | 20.48 | 19.97 | 18.88 | 18.24 | 17.39 |

| Chemistry | 10.08 | 9.98 | 10.31 | 9.31 | 9.15 | 9.18 | 8.55 | 8.64 | 8.00 | 7.86 | 7.70 |

| Physical geography | ........ | ........ | ........ | 22.44 | 24.93 | 24.64 | 24.33 | 23.75 | 22.88 | 22.42 | 22.22 |

| Geology | ........ | ........ | ........ | 5.52 | 5.20 | 4.93 | 4.66 | 4.41 | 4.02 | 3.88 | 3.48 |

| Physiology | ........ | ........ | ........ | 28.03 | 31.08 | 29.98 | 29.38 | 28.62 | 26.96 | 26.27 | 24.83 |

| Psychology | ........ | ........ | ........ | 3.35 | 3.82 | 3.82 | 3.64 | 3.23 | 3.19 | 2.98 | 2.53 |

| Rhetoric | ........ | ........ | ........ | 31.31 | 33.27 | 33.78 | 35.30 | 36.70 | 37.70 | 36.69 | 41.90 |

| English literature | ........ | ........ | ........ | ........ | ........ | ........ | 38.90 | 40.60 | 41.19 | 43.90 | 45.60 |

| History (other than United States) | 31.35 | 33.46 | 35.78 | 34.65 | 35.73 | 36.08 | 37.68 | 38.32 | 37.80 | 38.41 | 38.90 |

| Civics | ........ | ........ | ........ | ........ | ........ | ........ | 21.41 | 20.89 | 21.09 | 20.60 | 19.87 |

I have your letter of recent date referring to the remarkable increase in the numbers of students in certain studies in the high schools since 1890. When this office began to classify the statistics of secondary schools more than fifteen years ago it was found that many schools had been reporting a large percentage of elementary pupils as in the high schools when in fact they pursued no secondary studies. It required several years to devise a form of inquiry which would enable this office to eliminate the elementary pupils.

We now state in our summaries how many schools reported students in certain studies (see page 1652, report for 1902 sent under another cover). This was not done in 1890.

The three and a half subjects studied (the average mentioned in your letter) is not excessive. In many schools the minimum required is four subjects' each year.If the fact that students were reported in 1891 as studying on the average less than two subjects was because certain elementary pupils taking only one study were included and if high school students on the average pursue four studies, it would follow that about 70 per cent, of all students reported in the high schools were elementary students. This was of course not the case, and with the data at hand we can only conclude that in 1891 the studies pursued by many students were not reported, and that we do not know what percentage of students studied Latin at that time. It may have been 60 per cent. The percentage of students studying Latin has probably decreased, because relatively more students are now prepared for the college scientific course than for the classical course, while at the same time the percentage of graduates entering college has decreased. The percentage reported as studying Latin has decreased since 1898 when the figures may be assumed to have become more accurate.

The decrease in the number of students studying physics and chemistry is not, however, so easily explained away. It may be that in 1891 elementary students taking physics or chemistry were reported, whereas but few elementary students would take Latin. The percentage of girls has increased, and this would favor literary as compared with scientific studies. The figures for zoology and botany are not given, and in the increase of the number of studies open to secondary students, there would naturally be a decrease in the number studying each subject. Still there is reason to believe that physics and chemistry as taught in the high school and college are not attractive to students. Indeed, we have grounds for fear that the high school course as a whole is not as useful as it should be, especially for boys. The figures given in the table show that 42.49 per cent, of secondary students are boys, whereas the boys graduating from the high school are only 34 per cent, of the total number. Only about 20 per cent, of students—boys and girls—entering the high school stay to graduate, and in Boston only 10 per cent, of the boys who enter the high school remain as long as the fourth year.