Popular Science Monthly/Volume 92/March 1918/Fighting Off Aviators with Shotguns

Fighting Off Aviators with Shotguns

The sawed-off shotgun of the under

world is gaining laurels in a new field.

UNCLE SAM has decided that the shotgun is, under some conditions, as deadly as the machine gun, and his Chief Signal Officer has ordered that instruction in the use of the shotgun be given at every one of the sixteen aviation schools now running, or about to be established.

When war started, the aviator used to go up merely to scout. He took along a rifle and a revolver or automatic pistol. But he could do no harm with such weapons in an aerial combat.

Then came the light machine gun, and the start of real aerial warfare. Now the air fight is merely part of the game, nor is the report of the week's doings complete without mention of the fact that the side making the report lost three planes and the other fellows thirty.

Also, there is the fast increasing use of the plane in sudden swoops over the enemy trenches; the machines, although they fly low, travel so fast that they cannot be hit with any certainty. Here, at short range, the five shots from the automatic shotgun would prove more efficient than charges from the machine gun, because the machine gun fire is concentrated while the buckshot scatters. And of course, there is also the use of the shotgun against the opposing plane at close quarters, where the action is too fast for swinging the machine gun to bear.

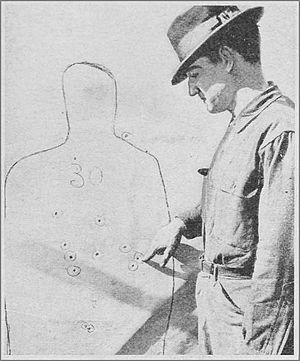

| At ninety feet all but one of the pellets bunched themselves well into the midriff section of a man-size figure fired at. At one hundred and fifty feet, seven out of the twelve hit the figure. At three hundred feet one shot missed the figure, two other shots put two pellets each into the figure, which is a disabling blow. |

Buckshot varies in size from the tiny pellet running twenty-seven to the ounce of weight, to the sort running only nine to the ounce. Usually but an ounce of shot is loaded for the 12-bore gun, and the powder charge is three and a fourth drams. For use against men at short range—less than fifty yards—the small size would be indicated. While it might not prove fatal in most instances, a few loads of this sort of pill would put the recipients in the hospital.

Number One Buck is just the size of the army bullet, .30 inch across, and weighs forty grains per pellet. Twelve pellets make an ounce and therefore the load.

The big, single, round bullet used in shotguns is another sort of missile that might well prove efficient in the hands of our aviators. Nothing shot out of a military rifle—outside of the rifle grenade—gives the tremendous shock and blow of the big .70 calibre, five hundred grain, round lead bullet that is used in the 12-gage shotgun. More than twice the size of the service rifle .30 calibre bullet, more than three times as heavy, and with a tendency to flatten out and hit still harder, the single ball for the shotgun, while not high in accuracy, is capable of knocking a man flat on his back if it hits him fairly. Five such huge pills, slung rapidly into an opposing aircraft, at a range of one hundred yards or less, would be like throwing five half-bricks into the machine with the velocity a half-brick never attained in this world.