Provincial Geographies of India/Volume 4/Chapter 1

CHAPTER I

GENERAL DESCRIPTION

Though politically and administratively included in the Indian empire, Burma is definitely separated from India geographically and its people differ from the people of India in race, speech, religion and manners. It may almost be said to be a part of India merely by accident. Separated from the peninsula by the sea and by ranges of hills, it comprises a distinct nation.

The remotest province of the Indian Empire, lying between 9° 58′ and 28° 30′ N. lat. and 92° 11′ and 101° 91′ E. long., it comprises an area of 261,839 square miles, in extent exceeding either France or Germany and far surpassing any other Indian Province. Its extreme length is over 1200 miles; its utmost breadth 575 miles. The whole territory is distributed into Burma proper, 164,411; Shan States, 54,728; Chin Hills[1], 11,700; unadministered tracts (estimated), 31,700 square miles[2]. A convenient division, in daily use, is into Upper and Lower Burma. The latter embraces all the country annexed in 1826 and 1852, that is to say, the Arakan and Tenasserim and the Pegu (now the Pegu and Irrawaddy) Divisions, including the whole of the sea-coast. The rest of the Province, that part which up to 1885 constituted the Burmese kingdom, is known as Upper Burma.

Lying on the east of the Bay of Bengal, Burma stretches from the borders of Tibet, Assam, Manipur and Chittagong on the north and north-west to the frontier of Siam. Northward from Victoria Point, the south-eastern extremity, the eastern front marches successively with Siam, French Indo-china, China.

Boundaries. A small section of the boundary in the extreme south is the Pakchan river. North of this, hill and mountain ranges mark the eastern frontier except where the rivers Thaungyin, Salween and Mèkong are the dividing lines. With China, the boundary was partially laid down by a joint Commission between 1897 and 1900 and was demarcated by

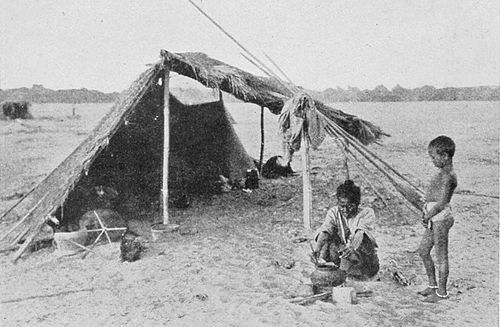

Fig. 1. A Burmese holiday.

masonry pillars, some erected in later years, as far north as the head waters of the Akyang river in about 27° 30′ N. The northern part of this boundary follows successively the Irrawaddy-Shweli and Irrawaddy-Salween watersheds. The extremity of the eastern boundary and the northern frontier facing Tibet, as yet undefined, are marked by lofty mountain ranges. On the west, other mountain chains separate Burma from Assam, Manipur and Chittagong as far as the estuary of the Naaf. Thence, west and south, to Victoria Point, the limit is the coast-line washed by the waters of the Bay of Bengal, the Gulf of Martaban and the Indian Ocean.

Geographically, without regard to administrative distribution, the Province may be regarded as consisting of five main divisions:

- (1) Central Burma, extending from the sea to Tibet;

- (2) Tenasserim, exclusive of the western part of Toungoo but including Karenni;

- (3) Arakan, omitting the northern Hill District;

- (4) The Chin Hills, with Northern Arakan;

- (5) The Shan country.

Central Burma. (1) Central Burma lies between the Arakan Yoma,[3] the Chin Hills, Manipur and Assam on the west, and the Sittang river, the Shan States, and China on the east. It is traversed throughout by the Irrawaddy river, partially in the north by the Chindwin. It may be sub-divided into the wet zone, the dry zone, and hill country. It must not be supposed that these divisions are marked distinctly like the squares on a chess board, but roughly the distribution is sufficiently accurate.

In the south lies the Delta of the Irrawaddy and the wide-stretching deltaic districts of Hanthawaddy, Insein, Pegu and Tharrawaddy. This vast expanse of country is a great alluvial plain. The true Delta includes all the districts of the Irrawaddy division, Bassein, Pyapôn, Ma-u-bin, Myaungmya, Henzada, a flat country intersected by countless rivers and creeks.[4] On the sea board and along the banks of streams and creeks are masses of mangrove and dani palm forest, tidal and swamp vegetation, elephant grass and savannah. In parts, as on the shore of Bassein, the coast consists of a gently shelving sandy beach but westward towards Cape Negrais, the one well-defined promontory, it is rocky and difficult to approach. Except in the north-west of Bassein and towards the head of the Delta in Henzada, where bordering on the Arakan Yoma is a hilly tract, there is no high land in all this wide expanse. But here and there crop up narrow strips of dry sandy soil

from four to ten feet above the level of the plain, called kôndan, supposed to be remnants of old sea-beaches. A great part of the Delta is flooded in the rains and is unculturable. But here is some of the richest rice land, much of it reclaimed and protected by embankments. The general aspect, in the rainy season, of Myaungmya, a typical Delta district, has been thus described by Mr S. Grantham in the Settlement Report,[5] published in 1921:

Along the edges of streams in the tidal area there is often a fringe of mangrove vegetation in which the kyi (Barringtonia) is plentiful and the lamu tree (Sonneratia acida) is prominent by its long arms stretched out over the water and occasionally

obstructing the narrower passages and by its numerous round breathing spires standing out of the mud between tide-levels. Through occasional gaps in this screen the passenger along the river in July spies what appears to be a second river flowing behind a screen of jungle which grows up on a narrow wall of tidal mud; but later in the rains the second river is seen to be a continuous stretch of water covering the paddy[6] fields with the tips of the plants standing out above its surface. In places in which brackish or salt water arrives, intervals in the mangrove screen are formed by dhani plantations, especially in the smaller creeks. In other places again, cultivation has been carried to the edge of the stream and the screen of mangroves is replaced by a narrow ridge on which grass or paddy is seen growing above the water. At neaptide, or later in the season when the paddy has grown tall, the edge of the land is more marked, but navigators are still glad to have posts and marks set up here and there to mark the course of the stream through what is apparently one great lake. The more northerly parts of the tidal

area are now completely cultivated in wide continuous stretches of paddy fields, broken up by streams with a fringe of jungle along their banks but including no extensive uncultivated parts. Travelling towards the south, the colonization becomes steadily more recent, more and more uncultivated land is met until at length cultivation is in rare isolated patches among almost continuous kanazo[7] jungle. Everywhere then, the background of the landscape is a high wall of kanazo growing along the courses of small streams crossing the cultivated plains or forming one face of extensive patches of jungle in the less cultivated parts, and in the south reaching often to the mangrove strip on the water's edge. Even in the cultivated and cleared portions odd trees often still remain as reminders of the kanazo jungle which formerly covered the whole. The river bank, built up by silt, is generally the highest land, but the streams sway to this side and to that as they erode their beds, and the bends tend to move along the course according to the ordinary fashion of river-action; the high ridge is therefore missing in places, the middle levels being contiguous to the rivers. Here, if the stream is large, the paddy suffers from the waves continuously beating upon it, and along the main rivers a fringe of jungle has commonly been left to break the force of the waves and screen the cultivation behind. The cultivators' villages are squeezed into small areas of land, which is uncovered at neap tide and sometimes at all ebb tides, and in lucky cases land is found for the village which is hardly inundated at all; generally these sites are along the banks of the smaller streams, the force of waves on the main rivers being an objection to building there. But commonly in the rainy season, and in the case of a large number for the whole year, the cultivators live in isolated huts or in small groups of two or three houses out in the fields. The highest available land is chosen and its level raised by layers of earth, and on that the house is built; and the whole family group of wife and dogs, cattle and children are accommodated in the closest association. The man and his cattle go out to plough; but except for an occasional journey to buy something to vary a diet of fish-paste and rice the wife may not leave for months this small area of thirty or forty feet square in which the children too must build all their houses, wage all their wars and hold all their pwès and processions, romping with the dogs or dyeing the chickens in their leisure hours.

The whole of the Delta is infested with mosquitoes.

The people generally recognize different varieties of mosquito, but in some places the general view is that expressed by an old Karen, who assured [Mr Grantham] there was only one kind in his village, and on further enquiry with a view to identifying that kind explained that it was "the biting kind." In the south and west the sand fly adds his bite to the other terrors of the insect world, and some people compare these parts to Nga-yè (hell), saying that the water is all salt, the country is always submerged, and the mosquitoes and sand flies are the masters and asking what further misery could be devised besides this of revising the settlement.

Yet, improbable as it may seem, over some minds the Delta exercises a singular fascination. Straggling villages, pagodas, monasteries, at rare intervals, vary the monotony

of the outlook. As one floats on a broad river or a winding creek with forest to the water's edge, at night with swarms of fireflies lighting the banks, many an aspect of calm and silent beauty is revealed.

East of the Delta are more vast stretches of rice-fields broken only by spurs of the Pegu Yoma in Hanthawaddy and Insein and by the Yoma itself which borders Tharrawaddy and traverses Pegu, clad with deciduous and ever-green forests.

The climate of all this country is hot and moist with a heavy rainfall. This is the busiest part of the Province with the ports of Rangoon and Bassein and other thriving towns. Negrais once regarded as a promising port has long been abandoned.

North of the Delta and deltaic plains lies the part of Toungoo west of the Sittang and the districts of Prome and

Thayetmyo approximately parallel with it. Toungoo is still in the wet zone, with rainfall heavy in the south and more than moderate in the north. Indeed, even the southern part of Yamèthin, the Pyinmana sub-division, adjacent to Toungoo, has fairly abundant rain. But Prome and Thayetmyo, on each side of the Irrawaddy, are distinctly hot and dry. In Prome and Toungoo are stretches of plain, as usual under rice cultivation. But a great part of these three districts consists of hilly country, spurs of the Arakan Yoma, the Pegu Yoma and its offshoots, and other less noticeable heights.

From the border of Thayetmyo up to about the latitude of the Third Defile[8] of the Irrawaddy extends the dry zone of Upper Burma. Between the Arakan Yoma and the Chin Hills on the west and the Shan Hills on the east, it includes the whole of the Magwe and Meiktila Divisions (with the exception of the Pyinmana sub-division), the Sagaing Division (except the Upper Chindwin district and the Chin Hills) and the districts of Mandalay and Shwebo. This tract includes wide areas of arid and sterile country sparsely covered with stunted vegetation, broad undulating table lands, rolling downs, barren plains cut up by many deep ravines, with frequent isolated hills rising abruptly from the plains. The Pegu Yoma begins in this area and runs through it from north to south. Elsewhere are other hill ranges. Pakôkku, Lower Chindwin, and parts of the Kyauksè and Mandalay districts are specially hilly country.

It must not be supposed that all this is a desert. Along the rivers are alluvial plains. In Minbu and Kyauksè a large irrigated area is under rice. Shwebo, formerly a dry plain, is now a flourishing rice district. The rice plain of Mandalay covers 700 square miles. On lands unsuitable for rice, products of dry cultivation, millet, sesamum, ground nuts, wheat, are largely grown. The hillsides are often covered with luxuriant forest growth. Sagaing is the only district altogether dry, without relief[9].

The great rivers Irrawaddy and Chindwin, and their numerous affluents, many of them mere beds of sand in the dry season, occasionally rushing torrents in the rains, as well as rivers of less volume in the east, traverse these dry districts. Meiktila is the only district in Burma, except Putao in the north, with no navigable stream.

In this tract are the city of Mandalay and the towns of Pakôkku and Myingyan. Here also are the famous oil wells of Yenangyaung. Of note for other reasons are the multitudinous pagodas of Pagan, most renowned in this land of Pagodas. Here the villages are more compact, each surrounded by a stout fence, sometimes of bamboo, sometimes of stiff cactus.

Though there are long dull stretches of river, with flat banks, there are also scenes of singular beauty. In the

midst, the conspicuous double peaks of Popa are picturesquely visible from the Irrawaddy for many miles. On the western and eastern borders the hills are marshalled in bold outline.

North of the dry zone lies a land of mountains and hills. Upper Chindwin on the west, with the Shan States of Hsawnghsup and Singaling Hkamti, bordering on the Chin Hills and Assam, bestriding the Chindwin river, is a mass of forest clad hills. Parallel with it, on either side of the Irrawaddy are Katha, Bhamo[10] and Myitkyina, with Putao in the extreme north. The part of Katha which lies on the right bank of the river consists mostly of hills with intervening valleys, but about Wuntho and northward from Mo-hnyin are fertile plains. Three well-marked mountain ranges traverse it and there are abundant forests. East of the river are strips of plain country; in the basin of the Shweli, the Shan State of Möngmit; and some sixty miles inland among rugged mountains the world-renowned Ruby Mines. Save for level country on the edge of the river, and for the plain of Hkamti Lōng in Putao, the Kachin Hills compose the three northern districts on the borders of China and Tibet. Stupendous mountain peaks and magnificent alpine scenery are characteristic of this remote part of the province.

Tenasserim and Karenni. (2) On the east and southeast lies Tenasserim, added to the Empire after the First Burmese War, nearly a hundred years ago. South-east are the districts of Mergui and Tavoy, a narrow strip of plain land on the sea coast, backed by hills towards the Siamese border; for the most part rugged and mountainous, covered with dense forests. The mineral possibilities of this country are great but lack of communications retards their development. North of Tavoy, Amherst consists of forest-clad mountains with broad alluvial plains between the Taungnyo and Dawna ranges, watered by the Salween, Gyaing, Ataran and Thaungyin rivers. The wonderful scenery is pictured in Crawfurd's vivid sketch of the view from Martaban, opposite the port of Moulmein:

At sunset we reached Martaban, about twenty-seven miles from the mouth of the river (Salween). The prospect which opens itself upon the stranger here is probably one of the most beautiful and imposing that Oriental scenery can present.[11] The waters of three large rivers, the Salween, the Ataran, and the Gyain meet at this spot, and immediately proceed to the sea by two wide channels; so that, in fact, the openings of five distinct rivers, are, as it were, seen in one view, proceeding like radii from a centre. The centre itself is a wide expanse of waters interspersed with numerous wooded islands. The surrounding country consists generally of woody hills, frequently crowned with white temples. In the distance are to be seen the high mountains of Zingai and in favourable weather the more distant and lofty ones which separate Martaban from the countries of Lao and Siam.[12]

Moulmein, the headquarters of the Division, is one of the chief ports of the province. North of Amherst is Thatôn, a plain country intersected by ranges of hills and half covered by forests.

Salween is a maze of mountains and woods, and so is Karenni, but with a well-watered plain in the north-west. The part of Toungoo, east of the Sittang, which completes this section, is also a hill tract.

Arakan. (3) The western part of Lower Burma is the Arakan Division including administratively the Hill District of northern Arakan which is geographically part of the Chin Hills. The rest of the Division lies between the Arakan Yoma and the Bay of Bengal. Arakan was annexed at the same time as Tenasserim (1826). Bordering on Chittagong on the north, it has usually been more readily subject to Indian influence than other parts of the Province. Embracing the districts of Sandoway, Kyaukpyu and Akyab, the Division consists of a strip of level country along the coast, broadening out to a wide plain in the north. Spurs of the Yoma fill the inland area extending nearly to the sea in the two southern districts. In the south is a rock-bound shore; further north the coast is indented by tidal creeks fringed by the ever-recurring mangrove and dani palm forests. North-east lies broken, hilly country, covered with dense woods. Kyaukpyu includes the large islands of Cheduba and Ramree. Akyab, the headquarters of the Division, is one of the principal ports of the Province with a magnificent harbour.

Chin Hills. (4) The Chin Hills include the district of that name in the Sagaing Division, the Pakôkku Chin Hills, and the Arakan Hill District, covering an area of some 12,000 square miles. This country occupies the western corner of Upper Burma, bounded on the north by Manipur, on the west by the Lushai Hills, on the south by Akyab, on the east by Upper Chindwin and Pakôkku. It is a mass of mountains intersected by deep valleys with no plain country whatever. In the Chin Hills district and the Pakôkku Hills, the ranges run from north to south, varying in height from 5000 to 9000 feet; the highest peak, Mt Victoria, in the Pakôkku Chin Hills, rises to 10,400 feet. In the Arakan Tracts, the hills do not average more than 3000 to 3500 feet in height. The whole Chin country is covered with dense forest, including pines and other trees of temperate climes, and in places glowing with masses of rhododendron. The savage mountaineers have been brought into subjection with much difficulty and are kept in order by military police posts. The headquarters are at Falam. Another principal post is Fort White, named after Sir George White, famous as the defender of Ladysmith.

The Shan States. (5) The great tract known as the Shan States extends along the eastern border of Upper Burma from 19° 20' to 24° 9' N. and from 96° 13' to 101° 9' E., covering an area of 54,728 square miles. It stretches eastward across the Salween as far as the Mèkong river to China, French Indo-China and Siam. In the north it marches with China; in the south with Lower Burma and Karenni. Its general aspect is that of a high plateau rising from 3000 to 4000 feet. The Myelat, bordering on the Meiktila Division, consists of rolling downs, with scanty growth of trees, intersected by ravines. East of the Myelat are hill ranges with intervening valleys; thence towards the Salween a wide well-wooded plateau, broken by isolated hills. East of the Salween is the great state of Kēngtūng and part of Manglün, the latter entirely hill country. Kēngtūng is broken and mountainous, divided unequally by the range which forms the watershed between the Salween and the Mèkong. Other trans-Salween areas are the mountainous country of Kokang and the territory of the Wa, a mere mass of hills. West of the Salween, in the north, is the extensive plateau of North and South Hsenwi and Hsipaw. Hsenwi is partly and Tawngpeng further north entirely hill country. The Salween runs through the Shan States from north to south and the Myitngè through the Northern States fromeast to west. Of the people, climate and administration, description is given elsewhere.

- ↑ The largest section of the Chin Hills has recently been constituted a district of the Sagaing Division; but they are sufficiently unlike other parts of Burma to justify separate classification.

- ↑ The unadministered area has lately been reduced.

- ↑ Yoma, hill ranges, in Pegu and Arakan, literally back-bone.

- ↑ A creek is not a small estuary but a stream, uniting larger branches, not in itself part of a main river. The word is in daily use but not easy to define.

- ↑ See page 120.

- ↑ Paddy=rice.

- ↑ "The kanazo is essentially a mangrove; although it attains the height of eighty to a hundred feet it stands upon soft tidal mud, supporting itself by wide-spreading roots, from which spring breathers which stand up above the surface of the ground and by means of their large stomata enable the roots to obtain the air which they require but could not get in the water-logged mud in which they grow."

- ↑ See p. 25

- ↑ Settlement Report, Sagaing. B. W. Swithinbank.

- ↑ By purists pronounced Bă-maw.

- ↑ Sir Richard Temple records a similar a similar impression.

- ↑ Crawfurd, 361.