Steam Locomotive Construction and Maintenance/Chapter III

CHAPTER III

FOUNDRIES

The work produced in the iron and brass foundries of a locomotive works is similar to that done in most general engineering foundries, except perhaps that locomotive cylinders are somewhat more complicated than those of most stationary engines. The moulding and casting of metals is a separate trade in itself, of which only the briefest mention can be made here.[1]

Iron and Steel Castings. The number of locomotive parts made of cast iron is now somewhat less than was formerly the case, steel castings now being used for many of the brackets, hornblocks and other details, on account of the greater strength and reliability of this material. Steel castings are, in fact, replacing many forgings as well. The art of manufacturing steel castings is a special one, and for this reason few locomotive works have their own steel foundries, and most of them find it easier and more economical to purchase steel castings from firms who have made a special study of the subject for years. Steel castings are used for wheel centres, motion plates, frame stays, horn blocks, driving axleboxes, dome seatings, bogie centres and various brackets and smaller parts.

Iron castings are used for cylinders, the drag-box under the footplate, the chimney, blast-pipe, and regulator-head in the dome, also for certain hornblocks, smaller axleboxes and brackets. Brake cylinders, brake blocks, firebars, sandboxes and on some railways the wheel coverings or “splashers” for goods engines are also of cast iron. This list includes castings of very varying types and qualities of cast iron. For instance, the cylinders are made of the very best close-grained iron of special quality and mixtures, and the greatest care is taken to produce a strong hard material free from any “honeycomb” or other defects, but at the same time the hardness must not be so excessive that they cannot be suitably machined and fitted.

At the other end of the list are the firebars, which are usually made of common scrap, much of which has had to be rejected as unsuitable for other foundry purposes.

It must not, however, be understood that scrap iron castings are inferior as a material. All the best castings such as cylinders contain a percentage of scrap iron varying from 15 to 50 per cent., but this scrap is best selected material, derived from old cylinders and best machine parts. The pig irons used are also selected with a view to the quality of the castings desired, and for cylinders it is usual to mix two different good grades of pig iron with a percentage of scrap. In a locomotive works where a large variation in the qualities of the different castings has to be made, the greatest skill on the part of the foundry foreman is required in selecting and grading his materials.

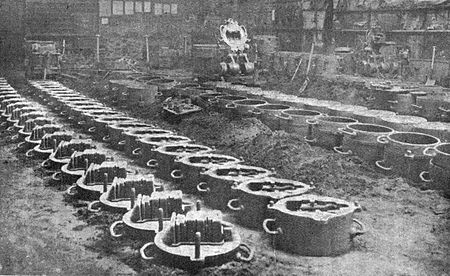

Moulding for General Castings. The various groups of castings require different methods of moulding. Many of the smaller pieces, of which a large quantity are required, are moulded by machine,- or “plate moulded.” In the latter case the patterns are of metal and cast or fixed on to a plate. If the shape of the article to be made allows of it, the whole pattern is placed on one side of the plate, but in many cases half the pattern is on one side, and the other half on the opposite side. The mould is then made in two portions, the second part being produced by turning the plate over. One of the main objects of plate moulding (apart from speed of output), is to save wooden patterns from being damaged by the constant knocking and shaking required to remove them from the sand. A large number of articles can be made from the metal patterns in plate moulding which are all of the same size without variation. Vacuum brake cylinders, which are very thin castings, are made in this way, and also many forms of smaller axleboxes, brake blocks, etc.

Fig. 8.—Axlebox Moulding Machines and Moulds.

G.W.R Swindon Works.

Cylinders. Cylinders are the most important and difficult castings made in the foundry. The difficulty lies in the number of complicated passages which have to be moulded by means of sand cores. If a passage has to be made in a casting, that portion of the mould which represents the passage must, of course, be filled up with a piece of special sand made to the shape and dimensions of the passage, so that when the iron is poured into the mould the metal flows round this “core,” which remains in place until the casting has cooled. Afterwards, when the sand “core” is removed, the desired passage remains in the casting. These cores are made in wooden core boxes, the two halves of which are made with cavities, and when put together form a hollow pattern for moulding the core desired. The cavity is filled with a special binding sand held together by laces and nails, and the core so formed is then dried in a stove and placed in position in the cylinder mould. To form a support for the core in the mould, the ends of the core are extended to form “core prints,” which rest in corresponding recesses in the mould. The steam and exhaust posts are formed from cores of this type, and the hollow cylindrical bore of the cylinder is formed by another large core.

All these cores are made of “loam,” composed of clay and sharp clean sand mixed together with cow-hair, which helps to bind the core, but more particularly makes it porous, so that the gases formed when pouring can escape.

Fig. 9 shows a view of the large iron foundry at the Great Western Railway locomotive works at Swindon. The moulds on the floor in the foreground on the left-hand side show single outside cylinders in various stages of the work. Two of these finished cylinders are being lifted by cranes. In the middle of the floor is a half pattern of a pair of inside cylinders, in front of which is an iron core barrel, on which the loam core for the bore of one of the cylinders is plastered, and finally “strickled,” i.e., the core barrel with the wet loam on it is rotated and the excess of loam swept off by means of a straight lath of wood until the core is of the proper diameter. After having been dried in a drying chamber, the barrel core is placed in its proper position in the mould. To hold it in position there are “core prints” formed in the mould. The pattern in the middle of the floor shows two of these “prints” on the front face.

All moulds must be rammed and “vented”

Fig. 9.—Iron Foundry.

GWR Swindon Works.

Inside cylinders were formerly cast separately and afterwards planed and bolted together to form a pair. Modern practice is to cast both inside cylinders in one piece. This requires more expensive patterns, but saves a lot of machine work.

Brass Foundry All the brass and gun metal castings are made in the brass foundry. These are much smaller pieces than iron castings and consist of axlebox brasses, injectors, cocks and taps, slide valves, and a host of miscellaneous details required in a locomotive. Much of the work is “plate moulding.” Various mixtures of metal are used from gun metal bronzes for slide valves and axlebox “brasses” to common brass for taps, etc. The metal is melted, not in large cupolas as in the iron foundry, but in plumbago crucibles which are heated in furnaces generally placed below the floor level.

- ↑ See also Patternmaking, by Ben Shaw and James Edgar (Pitman), uniform with this volume. Also Foundrywork by the same authors.