CHAPTER VI

THE LAND OF UZ

TO appreciate truly the significance of Damascus, one should approach it from the east, across the thirsty wilderness which stretches between the Euphrates and the Syrian mountains. The long, wearisome journey would be worth while if only for the first glimpse of the city as it appears to the wondering eyes of the desert-dweller. But the twentieth century visitor may be excused if he prefers to save time and strength by utilizing the railway. To-day there is even a choice of routes. He can travel to Damascus from the west comfortably, or from the south speedily. But the adverbs are not interchangeable.

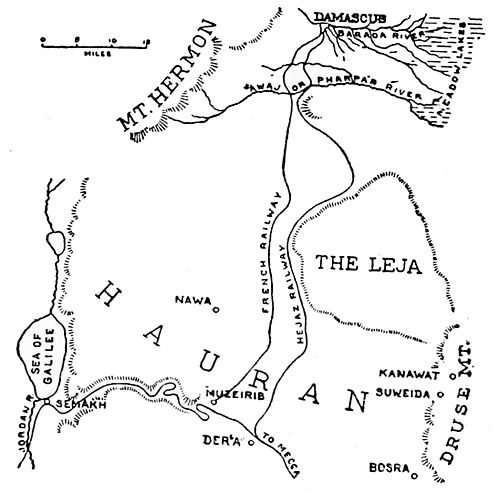

We have already taken the slow, beautiful journey from Beirut across the two mountain ranges. The other railway between Damascus and the coast starts from the seaport of Haifa, at the foot of Mount Carmel, and follows at first a fairly easy grade through the historic Plain of Esdraelon to the Jordan Valley at Beisan. From here it runs northward along the river to the Sea of Galilee,[1] then in a general easterly direction up the valley of the Yarmuk to the plateau of the Hauran, where the Haifa branch joins the main line of the Mecca railway. Although the distance to Damascus by this route is a hundred and seventy-seven miles, or almost twice that from Beirut, the journey takes no longer. But in warm weather it is not a very comfortable trip, for more than half the time the train is below the level of the sea.

From Semakh, which lies at the southern end of the Sea of Galilee six hundred feet below the Mediterranean, the railway ascends the Yarmuk gorge through the most wild and desolate scenery imaginable. The entire region northeast of Galilee is volcanic. Prehistoric flows of molten rock extended over large areas, and the subsequent erosion of the river has cut through a solid layer of hard basalt from ten to fifty feet thick, whose perpendicular black cliffs appear in striking contrast to the irregular outlines of the softer limestone beneath.

For two hours after leaving the Sea of Galilee we do not pass a human habitation; indeed, for the first few miles there is no evidence of vegetable life except now and then a small clump of bushes at a bend of the stream. As the train puffs slowly up the bed of the steep, twisting ravine, all that can be seen is the narrow torrent rushing madly along between white walls of lime or chalk, above these a smooth, regular layer of shining black basalt and, as we look straight up or down the valley, a few bare, brown mountaintops showing above the nearer cliffs. After a while, however, oleanders appear along the riverside, and for mile upon mile their thick foliage and gor-

geous flowers add the one touch of life to the wild, lonely landscape. We pass a strange monolithic pyramid a hundred feet high, which has been carved by some freak of the winter floods. A little farther on, a recent landslide has covered the bottom of the valley with black stones and soot-like dust. Even early in the morning it is hot and stifling in this breezeless trench below the level of the ocean.

As we rise higher, however, scattered olive trees appear among the oleanders by the riverside, and a few little patches of thin wheat are seen among the rocks. A small herd of black, long-haired goats are drinking in the stream. We are startled to behold a rude oil-well. A dozen men are gathered at each railway station, though the villages from which they have come are still invisible on the heights above us. Then the valley suddenly turns and broadens, and we see against the cloudless sky the clean-cut profile of the highland country toward which we have been so long ascending. The track now leaves the river's bank and, in great loops, quickly mounts the side of the valley. From the edge of the plateau there comes tumbling a magnificent succession of cascades, which finally roar under a railway bridge and break in spray at the bottom of the gorge far below us. Another broader waterfall drops in a solid sheet of silver from the unseen land beyond the level summit of the precipice. Our train twists up a last steep grade, straightens out on the level ground—and, after looking for three hours at the close cliffs which hemmed in a narrow valley, it gladdens our eyes to gaze now on the vast prospect which is revealed in the shimmering light of the noonday sun.

Before us stretches the Hauran, the ancient Land of Bashan, a rolling sea of soft brownish earth and waving wheat. From time immemorial this has been the chief granary of western Asia. Until we become accustomed to the new perspective, we can not distinguish a village or tree or living creature. Here and there a few apparently low hills show their summits above the horizon. The Arabs, who came from the high eastern desert, called this the Haurân, or "Depression," because it lies flat between the mountains. But to us who have climbed hither from a point 2,500 feet below, the broad acres of Bashan seem set far up among the lonely skies. An endless, level, undivided expanse of wheat; dim summits far away; fertility and spaciousness and freedom and strong, ceaseless wind—this is the Hauran.

Muzeirib, the first station on the plateau, is the terminus of the earliest railway from Damascus to the Hauran, which was completed by the French in 1895. During recent years this has suffered severely from the competition of the Hejaz Railway begun in 1901 by Abdul Hamid; for the Turkish line is somewhat cheaper, has better connections, and enjoys the odor of sanctity. In fact, its chief avowed object is ultimately to connect Damascus with Mecca and thus provide transportation for the multitude of the Faithful who each year make the pilgrimage to the holy city. Only Moslems were employed on the construction of this sacred railway, large numbers of Turkish soldiers were detailed as guards and laborers; and, besides special taxes which were levied, voluntary subscriptions for the pious enterprise were sent in from all over the world of Islam. On account of the revolution of the Young Turks and the troublous times which followed the enforced abdication of Abdul Hamid, no work has been done on the railway for several years. Already, however, it extends 823 miles to Medina, which is four-fifths of the distance to Mecca; but non-Moslems are strictly forbidden to travel beyond Ma'an, 285 miles from Damascus, without a special permit from the government.

Der'a, where we join the Hejaz main-line, has since the earliest days of Christianity been identified with Edrei, the capital of Og, the giant king of Bashan.[2] Beneath the ancient citadel, which stands some distance to the south of the station, is a wonderful labyrinth of caves, with real streets and shops as well as dwelling-places. This underground city doubtless was intended as a refuge for the entire population of the capital in time of siege, but it has not been used for many centuries.

As our train now turns northward from Der'a, Mount Hermon comes into full view at our left, in all its splendor of towering summit and dazzling whiteness, and the lofty blue cone with its long streaks of summer snow stays with us for the rest of the day.

Thirty miles to our right, Jebel Hauran, also known as the "Druse Mountain," rises from the level sea of grain like a long, low island. At such a distance we find it difficult, even in this crystal air, to realize that the isolated mountain is really forty miles long and only a little short of six thousand feet high. It is one of the few localities in the region where are still found the once famous "oaks of Bashan."[3] Since the religious struggles which drenched Syria with blood in 1860, many thousand Druses have migrated from Lebanon to the Hauran, where the special retreat and stronghold of this proud, brave, relentless people is the mountain which bears their name. Hither they flee from the conscription; here they defy the hated tax-collector, flaunt their contempt of the weak Turkish government and, as is their wont everywhere, waste their own strength in bitter family feuds.

A very ancient and plausible Christian tradition, which since the rise of Islam has also been accepted implicitly by the Moslems, identifies the Hauran with the "Land of Uz" where dwelt the patriarch Job. Three towns on the western slopes of the Druse Mountain perpetuate his story. Bishop William of Tyre, writing in the twelfth century, mentions the popular belief that Job's friend Bildad the Shuhite dwelt at Suweida, and the inhabitants of this village boast that the patriarch himself was their first sheikh. At Kanawat a group of very old ruins is commonly known as the "Convent of Job," and at Bosra, the ancient capital of the Hauran, there is a Latin inscription in his praise. Probably this belonged to a sixth century leper asylum; for the suffering patriarch early came to be considered the special patron of those who, like himself, were afflicted with the most mysterious and loathsome of diseases.

But it is in the plain that memories of this Biblical drama cluster most closely. Nawa, twenty miles northwest of Der'a, has for two thousand years been honored as Job's birthplace. An hour's ride to the south of this village there stood fifteen hundred years ago a splendid church dedicated to the Man of Uz, and part of the ruined "Monastery of Job" is still in good enough condition to be used as Turkish barracks. Near by is shown the rock on which he leaned while arguing with his three friends—it is a small basalt monument erected by Rameses II.—also the stone trough in which he washed after his afflictions were ended, and the tomb of the patriarch and his wife.

In spite of the naïve and often impossible localization of particular incidents of the story of Job, it is quite possible that the very old tradition is correct, and the mysterious Land of Uz across which roamed the herds and flocks of "the greatest of all the Children of the East" was this same free, fertile tableland along which we are now traveling. Before the Hauran was so largely given over to agriculture, it must have been, an ideal grazing country; it has always been subject to forays by robber tribes from the desert;[4] and the "great wind from the wilderness" which smote the dwelling; of Job's eldest son[5] would perhaps nowhere else blow with such fury as on this high, open plateau.

There was just such a great wind from the wilderness the last time I went to Damascus. The Hauran bears a deserved reputation for coolness and healthfulness; but that day, as happens two or three times each summer, there was a sirocco. The wind was indeed blowing—blowing a furious gale of perhaps thirty-five miles an hour; but it came straight from the eastern desert and scorched as if it had been a blast from an opened furnace door. I did not have a thermometer with me; but, from sirocco experiences elsewhere, I should judge that the temperature in the train was not under a hundred and five degrees. The drinking-water that we had brought for the journey became warm and nauseating; but we put it to good use in soaking the back of our necks, where it evaporated so quickly in the dry, burning wind that it stung like ice for a few seconds, and then was gone. Strange as it may seem, the only other way to mitigate the heat was to shut the car windows and keep the breeze out.

There were fortunately some interesting incidents to enliven the long; hot ride over the monotonous plain. We did not see any of the renowned "strong bulls of Bashan,"[6] or any other cattle grazing on the plain, but we watched slow caravans bearing wheat to the coast, as they have been doing for millenniums past. They could never carry all the grain that this productive district might harvest, and the railways should prove a rich boon to the Hauran. We pondered curiously as to why the stations were never by any chance just at the towns and why the track should swing far to the right and left in great curves, as if it were ascending a difficult grade, when the only engineering problem involved in its construction could have been solved by laying a ruler on the map and drawing a straight line down the center of the level plain. A fellow-traveler explained to us that the course of the railway had not been determined by the usual considerations, such as economy of construction and the desirability of passing through the most densely populated districts, but by the amount of bakhsheesh which wealthy landowners would pay the government in order to have the line pass through their estates.

We stopped an unconscionable length of time at every station, for no evident reason; and when we did get ready to start there were so many vociferous warnings that very naturally none of them was heeded by the passengers who had got off for refreshments. So finally the rapidly moving train would be chased by a crowd of excited peasants, most of whom carried big bundles and wore long, hampering garments. Several were left behind at lonely stations. There would be another train—to-morrow! Of course, all the dogs ran after us. Provided they are well-fed, dogs and children are exactly the same the world over; and these were not the starved, sullen curs which lie in Oriental gutters, but were wide-awake, fun-loving fellows who ran merrily alongside the train for a half-mile from the town, and had no difficulty in understanding our English shouts of encouragement. As we were pulling out of one of the stations, a very reverend, gray-bearded old farmer stole a ride on the running-board; but he misjudged the quickly increasing speed of the train, and, when he at last decided to jump off, rolled head-over-heels down the steep embankment. The last we saw of him, he was gazing after us with a ludicrously dejected countenance whose every lineament expressed stern disapproval of the nervous haste of these degenerate modern days.

As a rule the other travelers were too hot and tired to afford us much entertainment; but one new arrival, not finding a seat elsewhere, tried to force his way into the harem-compartment which Turkish railways always provide for the seclusion of Moslem ladies. The lord and master of the particular harem occupying this compartment resented the intrusion with such a frenzy of threatening gesticulation and insulting malediction that the members of our party who

Long, slow caravans have always been crossing the Hauran

Damascus in the midst of its far-reaching orchards

were unaccustomed to the ways of the East expected to see murder committed forthwith. The conductor, who interposed as peace-maker, was—as is usual on this holy railway—a Turk who knew no Arabic, and he consequently had great difficulty in determining what the quarrel was about; but the Syrians have a healthy fear of any one wearing a uniform, so the trouble was finally adjusted without bloodshed.

After we became accustomed to the peculiar features of the landscape we could now and then distinguish a village. Yet at a very short distance the largest settlements were blurred into the brown plain; for the houses are all built of a dull black basalt and, save for one or two square towers, the compact hamlets are hardly to be distinguished from rough outcroppings of rock. All of the dwellings look like deserted ruins: some of them are. All seem centuries old: many have been occupied for more than a thousand years, for the hard basalt seems never to crumble.

The extraordinarily rich earth of the Hauran is only disintegrated lava, and as we near the end of the plain we pass tracts where presumably more recent eruptions have not yet been weathered into fertile soil. Two or three miles to the east of the railway a long line of dark rock some thirty feet high marks the western edge of the Leja, which in New Testament times was known as the Trachonitis[7] or "Rocky Place." From now-extinct volcanoes at the northern end of the Druse Mountain there flowed these three hundred and fifty square miles of lava, which has broken in cooling into such a maze of irregular fissures that its surface has been likened to that of a petrified ocean. Yet this rugged region contains also little lakes, and pockets of arable soil, and numerous ruins of villages and roads and bridges which point to a considerable population in former days. Leja means "hiding-place" or "refuge," and the Druses call this forbidding district the "Fortress of Allah." The entire lava mass is honeycombed with caves. Indeed, the people of the Hauran say that one who knew the labyrinth of subterranean passages could make his way from one end of the Leja to the other without once appearing above ground. It is no wonder that this immense natural citadel, with its unmarked trails, its innumerable hiding-places in dark caves or deep-cut fissures of the rock, and its easy dominance over the dwellers on the level plain below, has always been a thorn in the side of whatever government pretended to rule the Hauran. Eighty years ago the Druses of the Leja, although they were outnumbered by the attacking force twenty to one, routed with terrible slaughter the entire army of Ibrahim Pasha, the great Egyptian conqueror.

The description of the Leja and its inhabitants which was written in the first century A. D. by Josephus would serve for any period in its wild history. "It was not an easy thing to restrain them, since this way of robbery had been their usual practice, and they had no other way to get their living, because they had neither any city of their own, nor lands in their possession, but only some receptacles and dens in the earth, and there they and their cattle lived in common together: however, they had made contrivances to get pools of water, and laid up corn in granaries for themselves, and were able to make great resistance by issuing out on the sudden against any that attacked them; for the entrances of their caves were narrow, in which but one could come in at a time, and the places within incredibly large and made very wide; but the ground over their habitations was not very high, but rather on a plain, while the rocks are altogether hard and difficult to be entered upon unless any one gets into the plain road by the guidance of another, for these roads are not straight, but have several revolutions. But when these men are hindered from their wicked preying upon their neighbors, their custom is to prey one upon another, insomuch that no sort of injustice comes amiss to them."[8] Josephus' diction is as involved as the labyrinthine trails of the Leja, but his facts are still correct.

Further evidences that we are in a volcanic region are found in the round black stones, about the size of large bowling-balls, which now begin to appear on the plain. At first they do not seriously interfere with cultivation, for the farmers gather them into heaps along the edges of their fields. A few miles farther on, however, there are so many that there has been no attempt to remove them and the light plow has simply scratched whatever narrow strips of earth might lie between the rocks. At last they cover the land as far as we can see, with hardly their own diameter separating them. There must be ten thousand of them to the acre. Millions upon millions of black spots dot the nearer landscape and in the distance merge into an apparently solid mass of dark, hard sterility.

By this time most of the passengers in our coach have become very tired and irritable, though the loud breathing of some indicates that they have fallen into a restless slumber. Several are quite sick from the heat. At half-past five in the afternoon the sun has lost none of its midday glare, and the noisy wind from the desert still scorches with its furnace breath. On either side, the monotonous multitude of round black rocks strew the brown, burnt earth. The hills, which constantly draw in closer to us, seem as if they might have fair pasture-land on their lower slopes; but, save for the shining white dome of one Moslem tomb, they bear nothing higher than scattered grass and dusty thorn-bushes. We climb slowly over the watershed in the narrow neck of the plain, then speed swiftly down a steep incline; and, lo, we behold a veritable paradise of running water and heavily laden orchard trees, above which the glory of the setting sun gilds a forest of slender minarets.

- ↑ See the author's The Real Palestine of To-day, chapter XV, "The War-path of the Empires," and XVIII, "The Lake of God's Delight."

- ↑ Numbers 21:33.

- ↑ Isaiah 2:13, etc.

- ↑ Job 1:15, 17.

- ↑ Job 1:19.

- ↑ Psalm 22:12, etc.

- ↑ Luke 3:1.

- ↑ Antiquities of the Jews, XV. 10.1.