Popular Science Monthly/Volume 45/July 1894/The Great Bluestone Industry

| THE GREAT BLUESTONE INDUSTRY. |

By HENRY BALCH INGRAM.

HOWEVER unhappy New York city may be in the matter of pavements between curbs, there is one fact apparent to the most casual observer, and that is that New York has the finest and best sidewalk pavements of any city in the universe. This is due to the fact that the sidewalks are largely paved with huge flat slabs of a natural product known in the commercial marts of New York as North or Hudson River bluestone. These slabs, which form smooth and dry platforms for the use of pedestrians, come from the quarries much in the same shape as they are laid upon the walks of nearly all of the Atlantic coast and many of the inland cities.

North River bluestone is a fine-grained compact sandstone, extremely hard and wearing upon a tool, and is made up of microscopic crystals of the sharpest sand. It abounds in inexhaustible quantities in a belt of country reaching from the Helderberg Mountains in Albany County, in this State, diagonally across the southeastern portion of the State and into Pike and Wayne Counties in Pennsylvania. The bluestone belt varies in width, being in the shape of a scalene or elongated obtuse triangle, no two sides of which are equal. In Albany County, at Reidsville and Dormansville, and Greene County, composing the northern extremity of the belt, the territory producing good marketable stone is narrow, being confined to the foothills of the eastern watershed of the Catskills and the southern slope of the Helderbergs. The stone quarried here is gray in color, with frequent tinges of

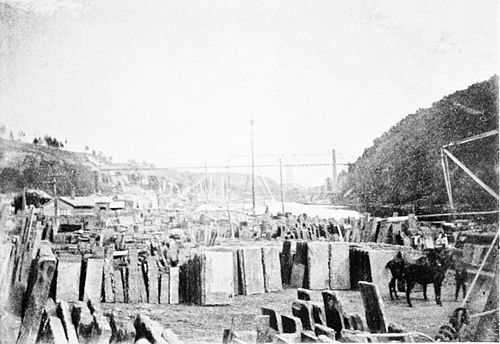

Fig. 1.—Bluestone Quarry at West Hurley, N. Y.

greenish and light-red and brown streaks, caused by the presence of calcite and ferric oxides. This stone is not regarded with favor by dealers, and brings a much lower price than the dark-blue product quarried farther down the river. The industry is also a vanishing one here, for the top matter to be removed in the quarries has become so heavy as the strata dip into the hills that few quarries pay to work at the present price paid for flagging stone. Many of the best-paying quarries of other days have been abandoned, and in consequence the ports of New Baltimore, Coxsackie, Athens, and Maiden, particularly the last, have declined very much in importance since the shipments of stone have fallen off.

The bluestone belt follows the Hudson River until the town of Saugerties, in Ulster County, is reached, when it takes a westward drift, being interrupted on the east by the older limestone formations, and on the north by the quartzose and. conglomerate or pudding-stone formations of the Catskills, the latter of which undoubtedly rests on a foundation of bluestone, as it again makes its appearance on the westward side of the range. In the town of Saugerties the gray color of the stone disappears, and the formation takes on the deep-blue tinge whence it gets its name. Here also the belt begins to widen, and when the broad plateau at the foot of the Catskills, covered by the adjoining towns of Kingston,

Fig. 2.—An Ulster County Monolith Size. twenty by twenty-four feet; nine inches thick.

Woodstock, Olive, Marbletown, Hurley, and Shandaken, is reached, the quarries are distributed over a range of country at least fifty miles broad. Here the stone varies but little in color, touching only the shades from medium to dark blue. The presence of ferric oxides is found in all the quarries, but only in the seams on the surface of the slabs, which have a rusty color from the oxidation. The stone produced in Ulster County has always commanded the largest prices, it being the best quality produced in the entire belt.

Leaving Ulster County, the bluestone belt crosses the Catskills, takes in a corner of Delaware and Orange Counties, and then crosses Sullivan Comity until the Delaware River is reached, where quarrying is carried on all the way from Port Jervis to Narrowsburg on both sides of the river. Very little quarrying is done through the mountainous districts, although many quarries have been opened with a fair profit in Delaware County along the line of the Ulster and Delaware Railroad, The stone produced here, as well as along the Delaware River, is of a deep-red color, contains large quantities of ferruginous matter, is of uneven texture, requiring more cutting, and is much inferior to the stone quarried in Ulster County.

The history of the discovery and first attempt to quarry bluestone for the market is shrouded in uncertainty. It is known,

Fig. 3.—Quarryman's Home with Rubbish Banks in Rear, West Hurley, N. Y.

however, that a man named Moray opened a quarry at what has since been called Moray Hill, near Kingston, as early as 1826. His son, the late Daniel Moray, of Kingston, said that his father was the first person to put bluestone as a product on the market, drawing the stone to Kingston with an ox team and selling it for window-sills and lintels. Philip Van de Bogart Lockwood was the most prominent producer of bluestone for many years after this, hauling the quarried product to the docks at Kingston Point, where it was loaded on sailing vessels and taken to the New York market. Later on, Abijah Smith built a dock and bought stone at Wilbur, which he shipped to New York, and in the early fifties the industry became so important that a plank road, eleven miles in length, was built on the Ulster and Delaware turnpike through the quarrying country, for the better trucking of stone to the docks at Wilbur.

Some of the quarries have been veritable gold mines. One in particular, known as the great Lawson Quarry, at West Hurley, is said to have produced over four million dollars' worth of flag and other classes of bluestone. This quarry was worked by Lucius Lawson, now of Chattanooga, Tenn., for fully thirty years, and in it nearly two thirds of a village of three hundred people earned their living. The great quarry has now been abandoned, as the top has got so heavy that it does not pay to remove it to get at the good stone. In consequence of its abandonment, the village of West Hurley has dwindled to less than one third its former size, and is rapidly becoming a deserted village. Hundreds of other quarries have been abandoned for similar reasons, yet the whole bluestone district of Ulster County is thickly dotted with new quarries, which are opened as soon as the old ones are abandoned.

In working the quarries there is a great difference in the thickness of the slabs taken out. The formation exists in perpendicular blocks of different surface dimensions which are formed of flat plates piled up like cardboard. The top of worthless stone and earth is first removed by blasting with powder, after which wedges are driven in the natural seams which separate the plates, lifting them up, after which they are hoisted out with derricks. In working a block the slabs may run to several thicknesses, varying from two to ten inches. The thin slabs are then cut up into what is known as Corporation four and five foot flag and smaller sizes, while the heavier blocks are preserved intact for such huge platforms as we see reaching from building to curb line on the sidewalks of New York. Many of the blocks worked are so small in surface area that they are unfit for flagging, and are consequently worked up in coping, pillar caps, window and door sills and lintels, building and bridge stone for tramways. Other blocks are found suitable for curb and gutter alone, while some quarries furnish slabs so small and thin that they are used only for floor tiling, or for the facing of brick walls. Again, some of the slabs, or more properly platforms, taken from the quarries are from twenty to thirty feet square, ten inches thick, and weigh over twenty tons. Owing to the difficulty in handling and the danger of breakage during transportation, these platforms are seldom taken to tide water, but are broken up at the quarries into more convenient sizes for handling. Sometimes, however, monoliths of tremendous size and weight have been transported to the docks at Wilbur, the one shown in the illustration being twenty by twenty-four feet in surface area, nine inches thick, without a flaw, and weighing several hundredweight over twenty tons. It was quarried at the Sawkill, in the town of Kingston, and is said to be the largest stone ever brought to tide water. It took eight horses to haul this monster to the docks over a stone tramway, and it is alleged that the side of a tollgate had to be taken down to allow the stone to pass through. In quarrying bluestone much stone that is practically worthless is met with. Sometimes what looks at first glance like a fine, straight-seamed block will be uncovered, when, at the first attempt to work it, it will break up into small pieces like a pile of brick. These blocks are known to quarrymen as cat faces. This formation exists in small blocks between all good working blocks, as well as sometimes in the

Fig. 4.—Shipping Dock on Rondout Creek at Kingston, N. Y.

larger ones. Cat faces are worked up into blocks for street paving, many having been used in the Hudson River cities, where they are set so the wear cuts across the grain, and have been found to wear superior to granite block, as they never become slippery, and furnish always a sure footing for horses. The worthless stone of the quarries, called rubbage, is hauled to the dumps, where immense mountains of broken stone, often one hundred feet in height and several acres in extent, have been built up.

The quarrying of bluestone and its allied industries furnish employment at good* wages to a large number of people. It is estimated that throughout the entire bluestone country—reaching from Albany County, New York, to the Pennsylvania region on the Delaware River—at least twenty thousand people get all or a portion of their support from the bluestone industry, while in the larger cities outside the bluestone belt hundreds of stonecutters are employed in dressing the stone. The wages run from a dollar and a quarter a day for common laborers to three dollars and a half a day for stonecutters, blacksmiths, tool makers, expert quarrymen, and other skilled labor. It would be hard to give a correct estimate as to the exact number of people who profit by the bluestone industry, as its influence is felt in all branches of mercantile trade, in lines of both water and land transportation, and, in fact, every industry throughout the district where the stone is found. To paralyze the bluestone traffic would mean to paralyze all branches of trade throughout that country.

Fig. 5.—Bluestone Sawing and Planing Mills at Kingston, N. Y.

The bluestone trade amounts to nearly three million dollars annually, two thirds of which is paid out in wages.

The manner of working bluestone after it leaves the quarries is worthy of notice. Before it is taken to the docks the stone receives only a superficial dressing. At the docks it is piled up, and such as is needed to fill immediate orders is sent to the cutting mills. Here the large slabs are laid on huge bed planers and planed smooth as a board. Others are sent to the saws, which consist of a gang of thin strips of plate iron, running horizontally over the surface of the stone. Under the edges of the saws, which are toothless, is kept a supply of wet sand very sharp in grain. The constant grinding of the saws in the sand soon cuts into the stone and rends it into slabs or bars of the required size. Other stone which is required to have a perfectly smooth surface is placed on huge revolving platforms of cast iron, the surface of which is kept covered with a thin coating of wet sand. The platform, revolving at high speed under the stone, soon rubs it smooth as polished metal—without the polish, however, as bluestone is not susceptible of polish. Other stone is dressed by hand by the stonecutters, who tool it with chisels and axes into different shapes. It is also turned in lathes in the shape of hitching posts, columns, and other forms, while it is susceptible of the most intricate carving, and is used at present in many classes of sculptured work for the ornamenting of buildings. Its extreme hardness makes it proof against all atmospheric changes, and it will neither shell like brownstone nor crumble like marble under the action of frost. It disintegrates and explodes, however, with terrific force under the action of intense heat.

The bluestone formation of New York State lying in Ulster County belongs to the Hamilton period, while that quarried in the other counties mentioned belongs to the Catskill group of rocks of the Upper Devonian age. As far as the writer has been able to learn, minerals are never found in the bluestone deposits, except in the form of oxides. Ignorant prospectors have at times reported the discovery of anthracite coal, which, however, has always proved to be a worthless deposit of organic slate, which in some localities abounds in considerable quantities. It is improbable that coal will ever be found in this region, as the stone formations that lie nearest the surface are those which underlie the coal measures of the entire country.