Copyright, 1914, by Jeff. C. Riddle.

All rights reserved.

Copyright of half tones and engravings from photographs or drawings in this book not specially copyrighted by others are protected by copyright notice, by D. L. Moses.

TO THE PUBLIC.

In writing this little book I want to say, I did what I thought was my duty. I have read so many different works on or about the Modoc war of 1872 and '73. The books I read were so disgusting, I must say that the authors of some of the books certainly were never in the neighborhood of the Lava Beds. They must have dreamt of the Modoc war.

I have read Capt. William T. Drannan's book, "Thirty Years on the Plains," where he wrote about the Modoc warriors. According to what he says, he captured and killed more Modoc warriors than Capt. Jack really had when he commenced fighting. Jack only had fifty-two warriors in all. I knew every one of them. It is such men as Mr. Drannan who mislead the public in regard to Indian wars. Mr. Drannan certainly was not anywhere near the Lava Beds at the time of the Modoc war of 1872 and '73, as I do not remember meeting him at that time.

In my work I aim to give both sides of the troubles of the Modoc Indians and the whites. The Indian side has never been given to the public yet. I have one drawback : I have no education, but I have tried to write as plain as I could. I use no fine language in my writing, for I lack education.

JEFF C. RIDDLE.

"This boy Char-ka, meaning in English The Handsome Boy, Jeff C. Riddle, will be heard from sometime in the future in behalf of his mother's

people." This statement was taken from page 71 of the book entitled "Wine-ma and Her People," by A. B. Meacham, Hartford, Conn., 1876. A prophecy that has now been fulfilled by the same Jeff C. Riddle, who has now

PREFACE.

Mr. Riddle, the author of the following history of the Modoc War, has included in his text all that need be said by way of foreword and introduction. He is himself a Modoc Indian, the son of the chief figure in that struggle, and he was an eye witness of most of the events that he describes. There have been other histories of the Modoc War and of some of these the author gives his opinion an unflattering one. Most of them were written from hearsay and naturally from the point of view of the white man. Here we have the point of view of the Indian, but it is a point of view that is consonant with accuracy and with impartiality. Mr. Riddle's story can speak for itself.

It may be said in conclusion, that it has been thought advisable to have the story practically as it came from the author's pen. Here and there a word has been changed where the meaning has seemed obscure, and an occasional date has been rectified, but with these exceptions, there has been no attempt either to correct the form or to embellish the language.

The present publication of Mr. Riddle's story may derive a certain opportuneness from the fact of its appearance on the forty-first anniversary of a racial struggle written in red upon the face of California history, and upon that of Oregon as well.

Wi-ne-ma, the Author's mother; present day.

TABLE OF CONTENTS.

Captain Jack's father and his people at home in the Tule Lake and Lost River Country.

Captain Jack's father calls Council.—Indians all attend.—Combutwaush attend also.—Legyakes ready to move against the white people.—Modoc Chief lays cause on the Pitt River Indians.—Captain Jack, a small boy at that time, says good words for the white emigrants.

Volunteers from Rogue River, Oregon, make a trip through the Modoc Country; killing done; joined by Ben Wright and his men.

Captain Jack becomes Chief of his people.—John Schonchin, Sub-chief, loved by his people.—No trouble with the whites.—Jack's orders obeyed.—Jack becomes a mighty trapper.

Captain Jack and John Schonchin hold Council with their people after talk with John Fairchild.—Jack tells the men not to offer fight if the soldiers come—"Depend on me, my people, I will do the right thing we will not be hurt."—The shooting between Scar-Face Charley and Major Boutelle.

Captain Jack and his people all arrive safe in the Lava Beds.—Captain Jack occupies the largest cave, known nowadays as Captain Jack's Stronghold.—Indians all live in different caves.—They make preparations for war.

Colonel A. B. Meacham again reappointed Peace Commissioner—Rev. Thomas and General E. R. S. Canby being the other two with Frank Riddle and wife, Tobey, or Wi-ne-ma, Riddle, as government interpreters.—They open up Peace Councils with Captain Jack, John Schonchin and their warriors.

The two Chiefs hold Council with their warriors all night, after the last Council with the Commissioners.—Jack taunted by some of his men, branded as a coward or a squaw.—Canby's life sealed, also Meacham's and Thomas'; Dyar and Riddle not to be spared.

Last Council, April 11, 1873.—Canby and Dr. Thomas killed.—Colonel Meacham saved by Tobey Riddle, althoough badly wounded.—L. S. Dyar and Frank Riddle make their escape.—Tobey Riddle struck down by Boncho, a Rock Indian.

Troops advance on the Modocs April 14th.—Hard battle for three days.—Indians show good marksmanship first three days of fighting.—Indians vacate their caves the night of April 18th, 1873.—April 26th, Wright and his company move on the Indians.—Troops routed.

May 7th, Captain Jack and all his braves go south about four miles.—Make another stand.—George, Ellen's man, killed, the bravest man among the Modocs.—His death causes trouble among the Indians.—The Modocs separate, one band went west and the other east.

Scar-Face Charley, Hooker Jim, Bogus Charley and Shanknasty Jim hired as Government Scouts, commence running to earth their own People.—Armed with nice carbines and riding fine grain fed horses, wages $100.00 per month.—These very men were eager to fight at the beginning of the Modoc War.

Colonel Mason gets orders to trail Captain Jack and Schonchin down.—Jack and his followers meet Ha-kar-gar-ush and his men and women near Steele's Swamp, Calif.—Ha-kar-gar-ush and Captain Jack make their camps together, north of Steele's Swamp a short distance.—General Wheaton with a company of cavalry men with Scar-Face Charley and Bogus Charley as scouts takes up Captain Jack's trail near Clear Lake, California, and follow it to their camp.—They had a sharp running fight for about seven miles.—Some Indians captured at camp.—None were killed on either side.

Hooker Jim and Shaknasty Jim overtook General Wheaton and his men on the south shores of Clear Lake and told them that they saw smoke north of Steele's Swamp, California.—Wheaton dismounts his troops and sends Bogus Charley and Scarface Charley to locate Jack and Schonchin.—Jack and Schonchin and Ha-kar-gar-ush found by the two scouts.—Wheaton follows with his troops and other two scouts and surprises the Indians in camp.—Captain Jack makes his escape, but is captured the next day near the head of Langells Valley, Oregon.

Colonel Mason sends messenger to John Fairchild's Ranch, California, stating to Jeff C. Davis, who was in command at that place, holding Black Jim, Curley Headed Doctor and some sixty or seventy other

Modoc prisoners, that he had Captain Jack and John Schonchin and their families and forty or fifty other prisoners.—Some at large yet.—General Jeff C. Davis starts with his prisoners second day after

he learned of Captain Jack's capture, arrives safe in two days' travel at Colonel Mason's headquarters, on the peninsula, Tule Lake, California.—Six wounded Modoc prisoners shot to death by Oregon Volunteers.

All the prisoners moved to Fort Klamath, Oregon.—Curley Haired Jack kills himself the first night they camped at the lower gap on Lost River, Oregon.—Soldiers arrived at Fort Klamath on the third day from the peninsula.—Captain Jack, Schonchin, Black Jim, Boston Charley and Boncho and Slolux on trial for murder in July.—First four condemned and sentenced to be hung October 3, 1873.

Captain Jack, John Schonchin, Black Jim and Boston Charley hung 3rd day of October, 1873.—Boncho and Slolux, or Modoc name Elulksaltako, sent to penitentiary in California, for life. The rest of the prisoners taken to Quapaw Agency, Indian Territory. Thus the Modoc War ends.

BIOGRAPHY OF TOBEY, WI-NE-MA RIDDLE |

Page 201 |

BIOGRAPHY OF FRANK RIDDLE, AND SON, JEFF. C. RIDDLE, |

215 |

BIOGRAPHY OF GEN. E. R. S. CANBY |

224 |

BIOGRAPHY OF REV. E. THOMAS |

230 |

BIOGRAPHY OF LEROY S. DYAR |

233 |

BIOGRAPHY OF JUDGE J. A. FAIRCHILD |

236 |

BIOGRAPHY OF COL. A. B. MEACHAM |

240 |

BIOGRAPHY OF CAPT. O. C. APPLEGATE |

250 |

BIOGRAPHY OF JUDGE E. STEELE |

260 |

MILITARY BIOGRAPHIES AND OFFICIAL CORRESPONDENCE, |

284 |

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

The Author and wife Frontispiece

Wi-ne-ma, the Author's Mother 5

George and Minerva Riddle 11

Sim B. Riddle 12

Bidwell Riddle 13

Captain Jack 18

John Schonchin 26

Hooker Jim 30

Bogus Charley 35

Capt. O. C. Knapp 36

Wi-ne-ma 40

Three Modoc Warriors and Judge J. A. Pairchild 42

Steamboat Frank 43

One-Eyed Mose 48

One-Eyed Dixie 49

The Fairchild Ranch : 51

Map of the Lava Beds, showing where Peace Commissioners were

killed 53

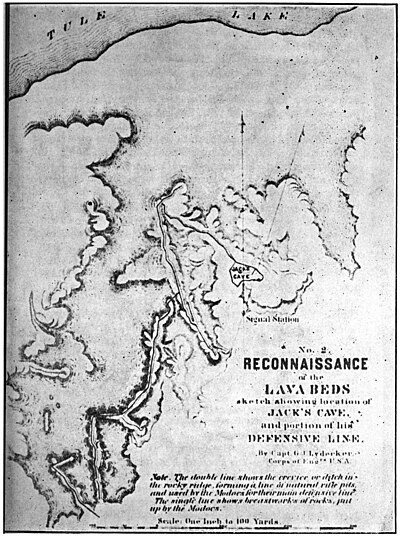

Map of Lava Beds, showing Capt. Jack's Cave 55

Judge A. M. Roseborough 59

Tobey and Frank Riddle's Cave G2

Capt. O. C. Applegate, Wi-ne-ma and four Modoc Squaws 68

William Faithfull 70

Captain Jack 74

Capt. Jack's Family 75

Gen. Frank Wheaton, U. S. A 76

Gen. E. R. S. Canby 78

The Peace Tent 82

Map of the Lava Beds and Vicinity 89

The Killing of the Peace Commissioners 92

U. S. Officers in the Modoc Stronghold 95

Gen. A. C. Gillem's Camp 9G

Soldiers' Quarters continuation of preceding page 97

Eugene Hovey 103

Scar Faced Charley 104

His Wife and Son 105

Gen. A. C. Gillem and Officers on the Modoc Campaign 106

Donald McKay and Scouts 112

Little Ike, or Dave 113

Capolis, Warm Spring U. S. Scout 114

U. S. Soldiers on the lookout for Modocs 115

Joe Sidwaller Bringing in the Wounded 116

The S. F. "Bulletin" Correspondent on the Battlefield 117

Capt. Jack's Stronghold 118

Warm Spring U. S. Indian Scouts 121

William, Warm Spring U. S. Indian Scout 122

Warm Spring U. S. Indian Scout 123

Warm Spring U. S. Indian Scouts 124

Capt. George, Warm Spring U. S. Indian Scout 126

Curly Headed Doctor 130

Ben Lawver 142

Schonchin's Rock 145

Shaknasty Jim's Camp 155

Curly Haired Jack and two Modoc Warriors 157

A Company of U. S. Soldiers at old Ft. Klamath 158

U. S. Soldiers in the Lava Beds 159

Old Chief Schonchin 1GO

Schonchin and Jack in Chains 1G2

Bird'seye View of all the Buildings at old Ft. Klamath 163

Officers' Quarters at old Ft. Klamath 165

George Denny, Slolux 190

Black Jim and Boston Charley 191

Old Fort Klamath, Present Day 192

U. S. Indian Agent's (old) Building, Headquarters Quapaw Agency 194

Peter Schonchin and Family 195

Henry Hudson and wife 196

Johnny Ball 197

One-Eyed Dixie 199

Martha Lawver 200

Wi-ne-ma, Present Day 201

Rev. Steamboat Frank, son and sisters 214

Frank Riddle 216

Wi-ne-ma 217

The Author when a boy 218

The Author, present day 219

Warm Spring U. S. Indian Scout 223

Gen. B. R. S. Canby 224

Gen. Canby's Cross 226

Grave of Gen. E. R. S. Canby 227

Panorama of the Lava Beds 229

Dr. E. Thomas 230

Plot where lie the remains of Rev. E. Thomas 231

Hon. Leroy S. Dyar 233

Princess Mary 235

Judge J. A. Fairchild 236

Toplash, a Modoc War Survivor 239

Col. A. B. Meacham 240

Grave of Col. A. B. Meacham 247

U. S. Grant (Modoc Warrior) and grandchildren . . . 249

Capt. O. C. Applegate 250

Allen David, a Klamath Chief 253

Capt. O. C. Applegate and Klamath Chiefs 257

Jim Winnishett 259

Judge E. Steele 260

U. S. Indian Agent's new building at Quapaw Agency 283

Modoc Prisoners' Children at Quapaw Agency School 292, 294

George Riddle, Minerva Riddle: the Author's eldest son and daughter.

Sim B. Riddle, the Author's second youngest son.

Bidwell Riddle, the Author's youngest son.

CHAPTER I.

Captain Jack's father and his people at home in the Tule Lake and Lost River Country.

Captain Jack's father and his people lived quietly on the shores of a beautiful body of water which was named Wrett Lake, or Tule Lake, California, by the white people. Jack and their followers were Modoc Indians. A few Rock Indians or Combutwaush lived on the southeast shores of Tule Lake.

The Modocs[1] and Combutwaush people lived a nice, peaceable life. They hunted the deer, antelope and bear on the hills and mountains that hemmed in Tule Lake. They shot the ducks and geese with their bows and reed arrows and caught fish in Lost River. The women gathered roots, cammus and wocus for winter use. They lived in peace and harmony with all the tribes that joined them from all sides. The other tribes were the Piute Indians, east; Pit Rivers, south; Shastas, west; and the Klamath Indians on the north.

They were living thus until the white people began to travel through their country; that must have been in the year 1848 or 1849.

Even then the Modoc people lived in peace for some time. On seeing the first emigrant wagon, with the people of a different color from themselves, they all ran for the hills. They thought that God had sent Evil Spirits among them to punish them in some way. But they soon learned that the white people were human, so they became friendly toward the emigrants. Every time any of them saw a train of wagons they would meet them. They liked the white man's bread, coffee, and other eatables that the emigrants gave them. It went on thus for several years.

Along about the year 1853, the Pit River Indians waylaid and killed quite a number of emigrants, both men and women, somewhere near the place where Alturas, California, stands now. Some of the emigrants made their escape and reached Yreka, California, and gave the alarm. The miners made up a posse of sixty-five fighting men and headed for the scene. Jim Crosby was chosen captain of the men. They went through the Modoc Indian country, met several bands of the Modocs and had no trouble with them.

The company went out to the scene of the killing; buried all the murdered they could find, but did not find any Pit River Indians. Although the company rode for miles around the surrounding country, their search for the guilty tribe was in vain, so they started on their return trip to Yreka, California. The company rode all day, and along towards evening, they struck camp on the east side of Tule Lake.

Some Modoc Indians visited the white man's camp the same as usual. The white people had treated the Modocs finely The very first white people that the Modocs had got close enough to had given clothes and flour, coffee and tea, bacon and blankets to them, so they liked the emigrants, for they had been treated so nicely by them. They were really glad when there were emigrants in their country. That was the reason the parties that visited Crosby's company were not afraid.

Captain Crosby gave the Indians some bread, bacon, etc. That night while Captain Crosby's men were asleep, there were about twenty Indians lying flat down on their faces, just a few paces from the lone sentinel or guard that was walking his beat. He knew the Modoc Indians were friendly, so he said to himself, "There is no hostile Indian in twenty miles of here; I guess I'll just sit down for a few minutes"; so he sat down. It was not long until he was fast asleep, so the twenty Indians wiggled towards their prey like snakes, now with their heads up and again with their faces close to the ground. The white boys were dreaming of their sweethearts or their homes. All at once their dreams were cut short. When they awoke, they heard the Indian warwhoop which was so well known by all the old frontiersmen. The most of the white boys went into the lake. Only one got a serious wound. Five or six others got hit by arrows. Capt Crosby emptied his six-shooter; he routed the Indians. The attacking Indians were the Pit Rivers. They followed Crosby and his company and attacked them in the Modoc country.

Capt. Crosby and his men left their camp early that morning. They had not gone far when they saw a few Modoc men and squaws. The Indians were preparing their morning meal. Crosby ordered his men to fire on the Indians, which they did. Only three Indians made their escape out of fourteen. That was the first Modoc blood spilt by white man. The ones that made their escape, went from village to village and spread the news that some of their number had been killed by white men, not in war; so the Indians vacated their camps. Some took to the mountains, others got in the thick titles, so they escaped Crosby's men. Crosby traveled clear around the north side of Tule Lake up Lost River, until he came to the Natural Bridge. He did not see any Indians. The whites crossed the Natural Bridge and headed for Hot Creek, known now as Oklahoma, California.

There they met some Hot Creek Modocs. The Indians were friendly. They did not know that the white people were seeking their lives. Instead of trying to get away, they came right up with their wives and children and said, "How do!" The answer was a volley from the white man's deadly guns. Only a few made their escape. Several women and children were murdered in cold blood, as well as men.

Capt. Crosby and his men reached Yreka the next day, after he had killed the last : mentioned Indians. The men had quite a few scalps to show to their friends, but they did not say that some of the scalps they carried were off poor old, innocent squaws and little children. The citizens in Yreka gave Capt. Crosby and his men a big dinner and a dance at night, in honor of his great brave deed that he had done. If the good citizens of Yreka had known the actual facts about the killing of the Indians by Crosby and his men, they would have hooted Crosby and his men out of town.

Crosby and his men boasted that they had two pitched battles with the Indians; that they were outnumbered in both battles. They did not say that they had fired on peaceable In- dian families and secured their scalps. It was such men as Crosby in the early days that caused the deaths of many good, innocent-hearted white people in the West.

CHAPTER II.

This Council took place about five or six months after the Modoc Indians had been killed by Crosby's men. Captain Jack's father in his opening speech said, in part: "My people, we was born in this country; this is our land. God put our fathers and mothers here. We have lived here in peace. Our fathers had some troubles with the Pitt River Indians and some other tribes. We always beat them. Now, my people, I see we cannot get along with the white people. They come along and kill my people for nothing. Not only my men, but they kill our wives and children. I did not give the white men any cause to commit these murders. Now, what shall I do? Shall I run every time I see white people? If I do, they will chase us from valley to mountain, and from mountain to valley, and kill us all. They will hunt us like we hunt the deer and antelope. Shall we defend our wives and our children and our country? I am not afraid to die. If I die in war against the white people, I will die for a good cause. Is there any one present that can say I am lost, or is there any one here that can say I am not saying what my heart tells me to say?"

After he said his last words he stood like one in a dream. Legugyakes[2] got up. He looked at every face before he said anything Finally he commenced by saying:

"I am a Combutwaush. I am a leader of my people. My people are only a handful. I have listened to the chosen words of the Mocloc Chief. He predicts the truth: we shall all be killed in time by the white men if we run every time we see them. I am not going to run. I am going to fight. I will get some of them before they get me. I say, fight! I am going to lead my men to the first white man's camp I see. I will see what they will do when they see their women and children killed, lying around dead, food for the coyotes, bugs, ravens and buzzards. My heart bleeds to know that we have been treated bad by the white man. If any of our people had stolen their horses or killed any of their people, then they would kill some of us. I would say that they are wrong. I say, as a leader among my people, I intend to kill the first white people I see. There is no one here that can turn my mind. I am going to do what I say."

When he finished his speech, he still kept his position by standing. A boy got up and made his way towards the center of the group of Indians. Perhaps the boy was fourteen years old, but small for his age. After reaching the place lie had selected to stand, he folded his bare arms across his breast, and stood with his head on his breast for some time. Finally he raised his head slowly, cast his eyes over the people, and said:

"Some of you men may think that I have no business to say anything in this Council. What made me get up and comeforward was this: I heard what my father said about our troubles; I also heard what Legugyakes said. I want to say, that both of our leaders are wrong."

Kind reader, this boy was Captain Jack. He was a savage, a born savage, but you will see what he tried to get his father to do at that time, and you will see also, after he took his father's place as a chief, how he tried to get along with the white people. The boy said in part:

"I am a Modoc; I am not afraid to die, but that is not it. We have not killed any white people yet, so let us not kill any. I know they have killed some of our people, but we cannot blame them. The white men that killed our people was attacked by Indians, while they were sleeping. A few of them got hurt. That was done in our country. These men thought the Indians that attacked them was Modocs. None of you has told the white people that it was the Pitt River Indians who made the attack. For my part I cannot blame the white people for firing on our people. If I was a man today, I woulld not plot against white people. The next white people that comes through our country with their families won't be responsible for the act of

the white men that killed our people many moons ago. Why

should we kill the innocent women and children ? It is wrong

to take life when not in war. I see that the white people are

many. If we value our lives or love our country we must not

fight the white man.

"Now I want to say to you, Legugyakes, if you kill any white people, I \vill see that my father shall not help you. M\ word I will make good if I am a boy."

So Jack's father came forward and said, "My people, you have heard what my son said. You all know that he is noth- ing but a baby. He is afraid to fight. He is afraid of death, but he has spoken some good words. I think I see in him a wise man and a good leader of our people when he becomes a man. I cannot take the words of my baby son ; I am like Leguyakes. I shall fight for my country that God gave me." So the council was called off by the chiefs.

One day an Indian was out hunting far from his village. He looked south. He shaded his eyes with his hand "and looked again. He said to himself, "I thought I could not be mistaken; it is many white people coming." He got behind a little ridge and started on a run for his village. He reported to Legugyakes the Combutwaush leader, what he had seen. Legugyakes said, "Tonight, when the stars are dim, will be our time."

Meanwhile a train of wagons was making its way through the eastern part of the famous Lava Beds where the Modoc Indians made their last stand in the year 1873. The jaded oxen and tired horses of the emigrants w'ere lugging the heavy wagons, with their high bows and white canvas tops. The train of wagons looked like a huge snake wiggling its way through that part of the Lava Beds. Some of the men were walking. The women and children were riding and happy. The men saw some Indian tracks, but thought nothing of it. The men were anxious to get over the next little raise. When the first man on horse-back rode over the raise, he waved his hat in the air, turned his horse and galloped back, met the wagons and told them that he had just seen a big lake.

The train moved forward and in a few minutes they called

a halt on the east shore of Tule Lake. After they had been

there a few minutes they pushed on, as the grass was not

plentiful where they stopped. The train moved on until to-

wards evening, and found a nice camp ground. This place

is two miles south of the California and Oregon boundary line.

The emigrants turned their horses and cattle loose to graze.

They gathered dry sage-brush and built their campfire to

prepare their evening meal, not knowing that the most of

them never would prepare another meal. Poor, innocent travel-

ers; they were all happy,for they knew that they would soon

reach civilization again, for after they consulted their maps

they knew they \vere on the shores of Wrett Lake, California.

About one mile northeast of the emigrant camp was a small

hill covered with black sage-brush and juniper trees. On

that hill Legugyakes and his men were laughing and talking;

joyful, for the prospects before them w r as an easy victory.

One runner had been sent to notify Capt. Jack's father that "many white people had stopped at Wa-ga-kan-na, this being the name of the place that the emigrants had camped at. (Wa-ga-kan-na means, at the little canyon, in the Modoc language). Jack's father called his men together and told them that many white people \vere camped at Wa-ga-kan-na, that Legugyakes and his men were going to attack them. He was going to help kill the white people that killed his people. Capt. Jack and some other boys were out from the camp playing. He saw the people astir in camp, so he ran to his father's lodge and asked his father what was the matter. His father told him. The boy caught his father and told him not to go. He cried and begged for him not to join Legug- yakes. "Let him do the dark deed, father," he says, "it's a coward's work to sneak up to any one and take his life."

"Father," he pleads, "it is bad enough to kill in battle. Do not lead your men to kill or help kill them poor people. They do not expect trouble. If you do help kill them white people, do you know, father, that you \vill be guilty of killing your own wife and your son and many of your own people. The white men will come here with more people than you have got, and kill us all."

OP THE MODOC WAR

The old man was headstrong; he called in his men; he told them to go with him one and all. "Do not listen to what my hoy says; he is young; he cannot lead me." The boy raised to his full height, faced his father and his men, and said, "Men, do not listen to my destructive father; he seeks the lives of all of us. If you do what he wants you to do; that is, kill innocent people, we are all doomed. The wise boy touched the hearts of the braves and only a few followed their chief.

Jack's father and Legugyakes met on the little hill and there sealed the lives of the poor emigrants. After supper the white people in camp sat around their campfires and, I suppose, talked about the new country they were going to, and about their homes that they had left behind, little sus- pecting at that time, that there was a strong body of half- naked savages watching their campfires, and wishing it \vas near daylight. The white men dropped off one by one to their beds to dream about their new homes they intended to build for their families. The fires went out one by one. At last the last fire died out, which the Indians noticed with glee. The emigrants had no guard out. They all slept the sound sleep of death.

About midnight some of the emigrants' horses got scared and snorted. None of the whites took any notice of it. The Indians were just a short distance from their sleeping vic- tims. The dawn of daylight found the Indians within striking- distance. They whispered to one another to lay down when it got good and light. One or two whites were up. They had just started the fires .to burning good. All at once about fifteen Indians jumped at the white men, howling like wolves.

The two men were struck down before they realized what was the matter. Nearly half of the white people were killed or wounded before they offered battle. Some of them were half asleep when they were shot with poisoned arrows. At last the emigrants rallied. They got their guns and com- menced shooting. The Indians retreated, leaving their dead behind. The white man's aim was good. After the Indians retreated to a safe distance, they got together and held a

council of war. They decided to send two runners, one south,

and the other north for help. Sometime in the afternoon the

runners got back to their comrades with many more blood-

thirsty savages.

Men and women were all astir at the emigrant camp, caring for the wounded, digging trenches, etc. The Indians renewed their attack about midnight, but were put to rout by the whites. Their aim was deadly. Soon as darkness was at hand the Indians commenced on the heart-stricken emigrants again. The white man's guns did not do any damage. All their shooting was guess-work. A few of the emigrants made their escape on horse-back in the forepart of the night. After midnight the rest of them made their escape. The first ones made their way towards Yreka, California; the others went towards Ashland, Oregon.

The Indians charged the emigrant camp next morning at the break of day, but were surprised to find that their intended victims had got away. Some of them said that none had escaped ; that they were all there dead. When it got good and light some of them found the tracks of their fleeing victims. None of them took up the trail ; they were too eager to loot. One Indian found a little girl ten or twelve years of age. He took her and said, "I will take this girl and care for her ; some day she can get among her kind of people; I will give her a chance. Now I ask a favor of all you men: Do not kill her." They all promised him that the girl would not be harmed. They divided everything among themselves ; they set fire to the wagons and burnt them. They left the dead white people lay where they had fallen. They all took to the mountains: some going north, some south, and others east.

The party that went north took the white girl along. After the party had gone about three miles the Indians got into a fight among themselves. During the mix-up the white girl was killed accidentally. She was left under a big juniper tree. Two days after the massacre there was a few Indians on the big mountain that stands north of the outlet of Lost River, watching a heavy dust that was raising up like a mighty cloud. The dust settled and it began to raise heavier than

ever, right close to the Natural Bridge, near where now stands

the beautiful town, Merrill, Oregon.

The cause of the dust \vas a strong body of hardy white men from Yreka, California. Some of the escaped emigrants had reached Yreka and given the news of the awful massacre. The citizens took to arms and were ready to start for the scene in less time than it would take a man to walk two miles. The writer's father, Frank Riddle, was one of the men in this company. If my memory serves me right, it was in the year of 1851. The captain of the men was from Ohio. His name was Al. Woodruff. Woodruff halted his men on the north side of Lost River, dismounted them, and they had a few crackers and some dried meat to eat. Some of them filled their pipes and began to smoke. Woodruff and Riddle were standing on some rocks about the middle of the river and were in earnest conversation for some time. Finally they both came ashore by stepping from rock to rock. Woodruff in- structed his men that if they sa\v any Indians, not to fire on them until he ordered them to. He said, "There are some Indians around hereabouts that are peaceable. We do not want to kill anyone that does not need killing, white or black. I know that all the Indians that lives here- abouts did not take a hand in 'his massacre. If they did, there would not have been one wh te person left to tell the yarn." The men answered by saying, "You are the Doctor, Captain." Before the men mounted to go, two Indian men and their wives came right up to the white men. By signs, they let the white men know that they had been up on Klamath Lake for nearly one moon. They knew nothing of the massacre.

Woodruff moved on towards the scene of murder at ;i lively gait. When they reached Wa-ga-kan-na they dis- mounted. The scene before their eyes was heart-breaking. Every man took his hat off. The men stood with their heads . down. When Woodruff spoke, the men raised their heads up, and every eye was wet. Some of the men's bodies shook with grief. They gathered the dead and laid them side by side in the trench, and covered them up, the best they could do under the circumstances. They went north perhaps a mile, and stayed over night. They were not disturbed during the night. The company took up the Indian trail the following morning and had not gone far when they found a little white girl dead under a juniper tree. Frank Riddle took his gray double blanket and wrapped it around the poor little girl's remains. He and some of the other boys dug a shallow hole under the tree and covered her over the best they could.

The company left the trail at this place, and started off west, reached little Klamath Lake that evening, camped over night, was on the road bright and early next morning, and met two or three bands of Hot Creek Indians. The Indians took to the rock and brush. Woodruff went on like he did not see them, and reached Yreka, California, the following day.

CHAPTER III.

The Modoc people were driven from place to place, after they left the mountains, and went back to Title Lake. After they massacred the emigrants at Wa-ga-kan-na, they went to the mountains, and lived there for nearly two years. They were the guilty parties. The Modocs that did not take a hand in the massacre continued to live in the valleys. The chief among them was Schonchin's father.

The whites named the place where the massacre took place, Bloody Point. The massacre at Bloody Point did not stop the white emigrants from coming through the Modoc country. Every little while there would be an Indian killed. It went on thus for some time. No more whites were killed in the Modoc country; some emigrants being killed out in the Pitt River country right along.

About the year 1856, month of June, about thirty-five men started for Tule Lake from Rogue River, Oregon. They came out to Keno, Oregon, and turned and \vent down the Klamath River and on to Yreka, California. When they got to Yreka they stated they were hunting Indians. There was a man by the name of Ben Wright who told them he would like to hunt Indians. The Oregon volunteers invited Wright to join them and go along; so Wright got some men that liked to hunt Indians to go with him. When they all got together they numbered over one hundred men. They all left Yreka some time in July to hunt down the Modoc Indians. They found some Hot Creek Indians, jumped onto them and killed a few. Wright was ths chosen captain of the company. Wright traveled all through the Klamath Indian country, kill- ing Klamath Indians wherever he could find them. He went through Goose Lake country, killed Paiute Indians wherever he got a chance. He came down Spragues River, Oregon, and killed a few Indians some place near where the Openchain ranch[3] is now. In the fall he went to Tule Lake and found some Indians. He did not attack them. He found one that could speak a little white man talk. He told that Indian that he was the Indians' friend. He or his men did not want to hurt any of them. He said he was a peace-maker. Said the Great Father had sent him to the Modoc country to make peace with the Indians. He told them that he would go away tomorrow to get some things for the Indians to eat and then they would have a big talk. Ben Wright and his men made his word good with the Indians. They all left the following day.

The Indian that had the talk with Wright spread the news among the Modocs and Rock Indians or Combutwaush that he had at last found a good friend. A white man with many men had told him he would be back in three or four days with plenty to eat for the Indians while they talked to make peace. The word went from village to village of the big feast and intended council. Three days after Wright and his men had left the Natural Bridge, forty-five men and a few squaws was camped near the Natural Bridge waiting Wright's return. They were anxious to be friends with the white people, and the prospects were good for a big feast. On the fifth day from the day Wright had left, he and his men all returned; all seemed to be very friendly with the Indians. They dismounted a short distance from the Indian camp. While Wright's men were busy pitching tents, Wright walked over to the Indian camp. He told them he would like all the Indians to move over near his camp. Said it would be much better when they would hold their council the next day, for if it kept raining they would be unable to hold an open council. We will have to get in my biggest tent; we will keep dry. The Indians agreed to his wishes. Wright located the camp site for them. He encamped them right on the bank of the river, where the river made a quick bend. Wright's camp was right back of the Indians' camp. They had the Indians hemmed in next to the river. The Natural Bridge was about half a mile southeast of this camp.Wright gave the Indians a whole beef and flour and other foodstuffs. The Indians were very happy. That evening they pulled up sage-brush and built wind-breaks and got tules and built shelters. The Indians and whites were having a jolly good time that night, until near the midnight hour. After midnight, everything was quiet. The whole camp was in slumber. The Indians little thought that that evening would be the last they would enjoy on this earth; their talk was, they were all glad that they had found a friend. Capt. Jack's father said he was tired dodging the whites. He seen a great future for his son and their people.

Long before daylight, if any of the Indians had been on guard they could have seen Ben Wright's men all up and looking after their arms. They could have seen men making their way down the river towards the Natural Bridge, carefully picking their way through the tall sage-brush. A few minutes after these men had left their tents, about forty in number, the Indians could have seen these same men on the north bank of Lost River, opposite their own camp, fingering the triggers of their muskets, assured by their Captain Wright, that they would have a fine morning's sport.

On the south bank of Lost River, where the two camps were, the rest of Wright's men were laying low behind their own tents, anxiously awaiting the brightness of morning to come. The sky begins to fade in the east, it gets quite light. Ben Wright looks along his gun barrel; he turns slowly, around to his men and says, "It is not light enough; we will wait till it is good and light. I want to get every mother's son of them Injuns. Boys, don't spare the squaws; get them all!"

The birds began to sing. Capt. Jack's father raises his head; he tells his squaw it is day. "Let's get up," he says; "it is raining. I wonder why the white people are not up?" The Indians begin to show signs of life. Capt. Jack's father was the first one up. He looked to his bow and quiver. It is still unstrung. All the rest of the Indians had unstrung their bows, because it was raining when they retired. Capt. Jack's father went towards his white friends' camp, looking for dry twigs, to start a fire. When he got even with the tents, he met Wright face to face. Wright drew his revolver and shot the Indian dead, and he yelled; told his men to be up and at them. The Indians all jumped to their feet, got their bows and offered fight, but could not do anything. The whites shot them down so fast on the south bank, they jumped in the river, thinking if they could make the opposite bank, they possibly could make their escape. When they got about half way across, the whites on the north bank opened fire on them. Only five escaped; every one of them wounded; quite a few squaws were killed. Not a man on the white side was hurt.

After the Indians had been butchered, Wright ordered the camp to hustle. It was not long till the Wright men were all traveling towards Yreka, California, with all kinds of Indian scalps dangling from their shot pouches. The second night after Wright's arrival at Yreka, the citizens gave Wright and his men a big dance. He was the lion of the day, and proclaimed the mighty Indian Hunter, Savage Civilizer, Peace-Maker, etc.

Died at Quapaw Agency, I. T. (Oklahoma), 1879.

CHAPTER IV.

Captain Jack becomes Chief of his people.—John Schonchin,[4] Sub-chief, loved by his people.—No trouble with the whites.—Jack's orders obeyed.—Jack becomes a mighty trapper.

Capt. Jack, though young and inexperienced as a leader, called a council. Told his people that through him, they, his people, would never be led in a trap and killed. "Now, we will go and see about our killed relatives." The second day after the Wright massacre, Jack's men and women were at the scene of the massacre. They gathered all they could find and cremated them. They only recovered about half of the killed; the rest had sunk to the bottom of the river. Jack kept watch along the river for months and recovered a few more of the dead.

Jack and his people dodged the white people for about two years. He never offered to kill any white people. He told his men that he wanted the white man as a friend, not as an enemy. Jack goes to Yreka, California, taking some of his men with him. He finds a man in Yreka that tells him he will be his friend and help him and his people. This man was Judge of Siskiyou County, California (Judge Roseborough). He proved to be a true friend to Jack afterwards.

Jack returned to his home on Lost River,[5] Oregon, in a few days, and told his followers that he and his men were well treated in Yreka, and had been assured by Roseborough (Big Chief, he called him) that he would be a friend to the Modocs. He told them, "I know he meant what he said; we will live in peace from now on. I will go and see Roseborough again soon; I want to find some more men like Roseborough."

In a short time he made another trip to Yreka. He was welcomed by the whites at Yreka. He stayed in town five or six days. Jack got acquainted with several leading men of Yreka, among them John Fairchilds, E. Steele, Pres. Dorris, and others. These men told Jack to live in peace in his country and he and his people would not be bothered. Jack was a happy man when he and his men left Yreka. Jack traded a pony for a lot of steel traps and it was not long till he was a very good trapper. His people went to Yreka every few days. After Jack's second trip to Yreka, along about the year of 1859, the whites began to settle in Capt. Jack's country. Jack and his people lived near the Natural Bridge, on Lost River, on both sides of the river. They welcomed the settlers. They got along fine; the settlers gave the Indians work, making juniper posts and rails, etc. Among the first settlers were Abe Ball, Brotherington, Miller, Boddys, George Nurse, Caldwell, Bibus and Overtoils. The most of these people settled on the north side of the Tule Lake, from Frank Adams' horse ranch[6] around the lake east. They all had horses and cattle. The Indians never bothered the settlers, and were not bothered in return.

Abe Ball had a cabin near where the Clint Vanbrimer ranch is now. Ball and one Indian named Skukum Horse were chums. Skukum Horse would go and stay over night with Ball any time he felt like it. Ball always was glad to have him around. One evening Skukum Horse went to Ball's, tied his pony and gave him hay the same as usual, and went to the cabin and knocked. Ball opened the door, but refused to admit the Indian. They had some hot words. Ball sent Skukum Horse away from his cabin door on a trot by the point of a gun. Ball had a visitor that evening. He did not want Skukum Horse to see who his visitor was. The visitor happened to be one of the Modoc's opposite sex. Ball and Skukum Horse met in a few days after they had the hot words. Ball wanted to explain things to his Indian friend. The Indian told him he could have told him who was with him that evening without getting so mad or threatening to shoot. One word brought on another. They had another falling out. They became hated enemies as the time rolled by. Ball and Skukum Horse never showed friendship towards one another again. The settlers kept coming into the Lost River country and made homes. The first man that settled in Langells Valley, Oregon, was a man by the name of Langell. The valley was named after him. The first man that lived in Poe Valley, Oregon, his name was Poe. Likewise the valley was named after him. Going back to Abe Ball, he lived on Lost River for a long time after he had trouble with his friend, Skukum Horse.

The country was getting pretty well settled up. Ball and his friend had another falling out in the year 1868. Ball wrote to Capt. Knapp, the agent at Klamath agency, stating that the Modocs were getting unruly; that they were killing the settlers' cattle and demanding flour and other provisions from the settlers. He was afraid that the Indians were preparing for war. He stated that the settlers were at the mercy of the savages. It was not long after Knapp got his first letter from Ball, he got another one from him stating that the Indians were giving war dances; stating that the bucks were getting bold, and there must be something done. He stated the settlers must be protected. Capt. Knapp then wrote to the Indian office in Washington, D. C., explaining Abe Ball's communications, whereupon Knapp got orders from the Indian office to investigate.

Col. A. B. Meacham, at that time of Salem, Oregon, was appointed Peace Commissioner by the government to go to the Modoc chief, Capt. Jack, and John Schonchin, sub-chief, and hold a peace conference with them. Col. A. B. Meacham, I. D. Applegate, John Meacham, George Nurse and Gus Horn and a company of soldier cavalrymen were ordered to go in November, 1869. The writer's father and mother, Frank and Tobey Riddle, were the interpreters. The writer, who was a small boy at that time, was present at the peace council. The peace council was well attended by the Modocs. They all agreed to go to Klamath Agency, Oregon, immediately, providing that Peace Commissioner Meacham would promise to protect them from the Klamath Indians. Meacham told them that they would be fully protected by Capt. Knapp, then agent for the Klamath Indians. Jack and Schonchin agreed to be ready to start with their people the next day for their new home on the Klamath reservation.

The next morning Capt. Jack was ready with all his people for the journey. It took eight big government wagons with mule teams to haul the Modoc women and their clothing, etc., up on the reservation. The point is known as Modoc Point today, named on account of the Modocs being settled there in November, 1869.

Jack in a few days had all his people well settled. About the month of December he called on the Indian agent, Knapp, at the agency. He told the agent that he wanted chopping axes, cross-cut saws, wedges and maul rings. He said he wanted to put his men to work making rails, etc. Agent Knapp furnished Jack with what he asked for. Jack went home to the Modoc settlement happy. In a few days the Modoc men were working- like beavers. They made nine hundred pine rails in a very short time. It commenced to snow. Jack told his men to quit for the winter, as it was bad weather; but as soon as the weather would get good in the spring, they would commence making rails again. It only snowed a day or so and quit. The snow soon melted off. Jack concluded to commence work again. The Modocs went out one morning to work. Only split a few rails. Along came five or six Klamath Indians with their wagons and teams, and loading their wagons with the rails that Jack's men had made, drove out of sight in the timber. Jack and his men did not stop work. Jack told his men that the Klamath Indians wanted to pick a fuss with him, but we shall not quarrel with them or fight them. If they come and load more rails in their wagons, I shall ask them who gave them authority to haul away our rails. While he was talking thus to his men, the Klamath teams again came in sight. The wagons stopped at the rails again. The work of loading rails commenced by the Klamath Indians. Jack walked slowly over to where the Klamaths were busy. He asked one of the men who had told them to take away the rails. The Klamath Indian struck himself on the breast and said, "I did." The other Klamath Indians ran up to Capt. Jack, got all around him and took turn about and told him that was their country and all the timber belonged to them. One old Klamath man said to Capt. Jack: "I am a Klamath Indian. This is my land. You have got no business to cut my trees down. This is not your country or land. The grass, water, fish, fowl, deer and everything else belong to me. I will take all the rails or posts you and your men make. My agent will protect me and all my people. You, Capt. Jack, cannot help yourself. Tule Lake is your home. Go there and live, and do what you please." At this juncture Jack replied, "I am a Modoc; I am not afraid of you, but I will not quarrel with you or your people. I think the agent will protect me

Bogus Charley, Modoc warrior. The reason he was called Bogus is, he was always telling jokes on the people. He died on the train while en route to see his sister, at Walla Walla, Wash., 1881.

and my people." As he said his last words, he turned his back on the angry Klamaths, and walked back to where his own men were still at work. He called his men together and told them what the Klamaths said to him. "Now," he said, "we shall quit for the present. I do not want any of you to quarrel with these Klamaths. I will take you, Bogus Charley, and go this very day and see the agent. I think he will protect us." They all went back to their camps. Jack and Bogus Charley started immediately for the agency, a distance of about eight miles. On their arrival at the agent's, they were met by a crowd of Klamath Indians. The Klamaths taunted them; told them they were all cowards. Jack and Bogus Charley worked their way through the crowd and got into the

Capt. O. C. Knapp, U. S. Agent at the Klamath Reservation, served in the Union Army during the Civil War and was promoted twice for gallantry and meritorious services at the battle of Mission Ridge, Tennessee, and during the Atlanta campaign. Honorably discharged at his own request, returned to his home at Bellefontaine, Ohio, where he died April 16, 1877.

- By the kindness of the Rev. E. M. Knapp.

agent's office. Mr. Knapp was in. He asked Jack what he could do for him. Jack told him about making the rails, about the Klamaths hauling them away, and what the Klamaths had told him. He told the agent he did not want any trouble with the Klamaths. "I have come to you for protection," said Jack.

Mr. Knapp said to Jack, "Perhaps, if you move your people up Williamson River a few miles, the Klamaths will not bother you. Let your rails go, Jack, and move your people right away. If these Klamath Indians bother you after you get to work upon the river, I will attend to the fellows, but by all means, Jack, don't fight any of them. Leave everything with me. Jack thanked him. Jack and Bogus Charley got back to their settlement in the evening. Jack called a council that night. He explained everything to his sub-chief, John Schonchin, and his people. The two chiefs decided to move in a few days, which they did. The Modocs settled north five miles up the river from their first settlement at Modoc Point. They did not do any work of any kind the rest of the winter. The Klamath Indians visited with the Modocs frequently They got along tolerably well. In March, 1870, the Modoc Indians and nearly all the Klamaths went fishing on Lost River, ten miles east of Linkville, now called Klamath Falls, Oregon. The Klamaths and Modocs all went back to their homes on the reservation in April. Jack and his men commenced making rails again, near their new homes in May. Had only made three hundred when the Klamath Indians commenced to haul them off. Jack stopped his men. He told them that he and Bogus Charley would go and consult their agent. They went and saw the agent. Jack told the agent what the Klamath people were doing. The agent replied: "You black son of a b; dm your Heart; if you come and bother me any more with your complaints, I will put you where no one will ever bother you again. Now, get out of here and be dm quick about it, too." Jack stood with his arms folded across his breast. He said, "Bogus Charley, tell this man that I am not a dog. Tell him that I am a man, if I am an Indian. Tell him that I and my men shall not be slaves for a race of people that is not any better than my people. If the agent does not protect me and my people I shall not live there. If the government refuses to protect my people, who shall I look to for protection?" Bogus and Capt. Jack went back to their settlement with sad hearts. Jack called a council that afternoon, and said to his followers: "I have been to see our agent. He threatened to kill me. He sent me out of his house. He will not protect us. He must be afraid of these Klamath people. I do not want my men to be slaves for these Indians, and they shall not be. My people are just as good as these Indians here. I am not afraid of them, but I shall not fight them. I am going back to my own country. If I stay here I will be killed. I know it, for I cannot stand for what the Klamath Indians do and say. I just as well die in my own country." Next day in the forenoon, Capt. Jack and his entire band of Indians was back on the banks of Lost River on their old camping grounds. Some of the Modocs visited their friends, the settlers, and told the settlers that they could not get along with the agent and Klamaths. One man by the name of Whitney, said he was glad to see them back. "There is plenty of room for all of us here. I know we can get along fine."

Jack's people all went in different directions in the month of June, 1870, to gather roots. The men all happy, some of them went to work for the settlers. They did not have any trouble with any of their white neighbors. Abe Ball, Skukum Horse's friend, had left while the Modocs were on the reservation. Jack's people went to Yreka quite often. The white people did not harm any of Jack's people; neither did the Indians bother the whites. The Modocs led and lived happy lives until September, 1872. Some of the white men told Scar-Face Charley that the soldiers would be after them soon.

John Fairchild rode one day into Capt. Jack's camp on Lost River. That was in October, 1872. The people gathered around Fairchild, all glad to see him. Fairchild was one of the best friends the Modocs had. Whenever he told them anything, they believed him. Fairchild told them that day that he was pretty sure the troops would be after them next month. He told them not to offer battle, but to go with the soldiers to the Klamath agency. He told them the soldiers were like them black birds, pointing to a flock of black birds. Scar-Face Charley told Fairchild that if the soldiers did not open fire on them they would not fight. Fairchild bid the Indians farewell and left for his ranch in Hot Creek, California. CHAPTER V.

Captain Jack and John Schonchin hold Council with their people after talk with John Fairchild.—Jack tells the men not to offer fight if the soldiers come—"Depend on me, my people, I will do the right thing—we will not be hurt."—The shooting between Scar-Face Charley and Major Boutelle.

November 28th, 1872, the agent at Klamath agency sits in his office reading a telegram from the Secretary of War at Washington, D. C. The message read like this: "Major Jackson, Fort Klamath, Oregon: Go to Lost River and move Capt. Jack and band of Modoc Indians onto the Klamath Indian reservation, Oregon; peaceable if you can, but forcible if you must."

Tobey Riddle rode towards Lost River from Yreka, California. She pats her bay mare on the neck, saying, "This has been a hard trip for you today. I will soon get there. Snippy, but we cannot stay long at Capt. Jack's camp. We must go on tonight towards Yainax." Tonight the noble animal strains its every nerve. She goes away in a fast trot, then at a gallop, then off like the wind. At last she reaches the top of the small ridge. She stops her faithful mare, looks long at the white specks of canvas at Jack's camp, and says to herself, "I guess my people are safe yet!" In a few minutes Tobey is among her people. They gathered around her. She tells in these words, "I am glad to see all of you. I left my home this morning about fifty-eight miles. I cannot stay overnight here. I must go on to my father and brother." Jack replies, "Cousin, you look tired and anxious; what is the matter? Your folks are just over the hill at Nuh-sult-gar-ka. Your brother, Charley, is better. Did you hear of him being sick?" Tobey shook her head. She was crying. After she overcame her grief, she said, "The soldiers will be here tomorrow. I rode hard in order to reach you people. What I want to tell you is this: "Do not resist the soldiers. Do not offer fight; if you listen to the officers, you people will not

This photo was taken in Washington, D. C., 1875.

From the Smithsonian collection.

While Jack was still talking, Tobey Riddle mounted her trusty animal. She reined her animal around and said, "Farewell, my people, we may never meet in this world again, but if you people just take my advice, you will all die natural deaths, one by one, near your native country." She tapped her trusty animal on the neck. The mare started in a gallop on the trail headed for Nuh-sult-gar-ka, where now stands the town of Bonanza, Oregon. Tobey arrived at her destination long after sun down, told her folks that the soldiers would be after the Modocs, over on Lost River tomorrow. Some of the Indians packed up that same night and made their way towards Yainax, Oregon. The ride Tobey Riddle made was on the 17th day of November, 1872. The distance this woman rode on that short November day was about seventy-five miles.

As soon as Tobey left Capt. Jack's village on Lost River, Oregon, near the Natural Bridge, Scar-Face Charley, Shaknasty Jim, Bogus Charley, Steamboat Frank, Hooker Jim, Skukum Horse, Curley Headed Jack and others got their ponies and started around the north side of Tule Lake to see the settlers. They told the white settlers; namely, Boddys, Brotheringtons, Overtons, Miller, Bibus, Browns and all the others that the soldiers would be at their village the following day. If the soldiers did not treat them right, they were going to fight. "We came here to see you men. All we ask of you men is to stay at your homes. Take no hand against us. We promise that not one of you will be hurt. Just stay at your homes. Let the soldiers lick us." The settlers all promised to stay at their homes. The Indians went back to their villages, well satisfied with their mission. After sundown a company of soldiers, cavalrymen, commanded by Major Jackson, was dismounting near a ford on Lost River, four miles from the Indian village up the river. The ford is now called Stukel Ford. The commander told his brave soldiers: "We will wait here till near the morning hour; then we will go down

Left to right: Shaknasty Jim, Modoc warrior; Indian name Ski-et-tete-ko, meaning left-handed person. Hooker Jim, Modoc warrior; Indian name Ha-kar Jim, meaning Let-me-see. Steamboat Frank, Modoc warrior; Indian name Slat-us-locks, meaning sitting down clumsily. Judge Fairchild of Yreka, Cal.

and pay the reds a visit." Eight or nine miles southeast of the company of soldiers, fifteen or twenty settlers had collected together in one of the settler's homes, and were talking about the war. They were preparing for war against the Modocs.

Kind reader, these men are the same men that had promised Scar-Face Charley and his men that same evening, that in case the Modocs got into a fight with the troops, they would stay home and do as the Indians had requested them to do. Capt. Jack and John Schonchin stayed up till a late hour that night, trying to reach some conclusion for the following day. They decided one and all to not offer battle, unless the soldiers forced them to fight. All of the Indians went to their lodges and were soon sleeping, not thinking in the least that they

Steamboat Frank, a Modoc warrior. Indian name Slat-us-locks, meaning sitting down clumsily. Died in Oakland, Maine, 1885, while studying for the ministry under the auspices of the Society of Friends.

would be routed by daylight. There was not one of them but what thought the soldiers would come to their villages in day time. They soon afterwards found out that was not the case.

Long before the dawn of day on the morning of November 29, 1872, the soldiers were on their way down Lost River, headed for the Modoc village on the south bank of Lost River. The captain called a halt about one mile from the village, told the boys it was too dark to good shooting yet. "We will go on when it gets lighter," he says. If one could have penetrated the darkness, he could have seen fifteen or twenty men, less than a mile from Curley Headed Doctor's lodge, and four or five other lodges on the north bank of Lost River, straight across from Jack's lodge. This body of men are the settlers. These men were very anxious to secure a few Modoc scalps at the risk of their own lives.

The Indian dogs had been barking nearly all night. The old squaws had been very uneasy on account of the barking of the dogs. One or two of the old women did not go to sleep all night. Just at daybreak, one old woman went out and started up the river. She was on the south side. She had not gone but a short distance when she discovered the soldiers advancing. She turned, got back in the village and gave the alarm. Every Indian was up and dressing in no time to speak of. One of the braves jumped in a canoe and paddled across the river and told the Indians on the north side that the soldiers were right at their village. One of the Indians on the north side of the river went out to see about his pony he had picketed. He run onto the settlers. The men told the Indian they had come there to watch the battle, if any should take place. The Indian let on as if he believed what they was telling him. At the same time he told the writer, afterwards at Yainax, he was expecting every moment to be struck down. The Indian's name w<as Little Tail, now deceased.

The soldiers rode right up to Capt. Jack's lodge and stopped.. Then they advanced a few steps on foot, and halted. By that time the braves were all around through the village. Major Jackson demanded Capt. Jack. Scar-Face Charley told the major he would go and get him. Jack appeared in a few minutes. A few of his men were with him. Every Indian had his gun with him. Jackson told Capt. Jack that the Great Father had sent him to go and get him, Jack and all his people and put them on the Klamath reservation. Jack replied, saying, "I will go; I will take all my people with me, but I do not place any confidence in anything you white people tell me. You see you come here to my camp when it is dark. You scare me and all my people when you do that. I won't run from you. Come up to me like men, when you want to see

OP THE MODOC WAR

or talk with me." The major assured Jack he did not want any trouble. He says: "Jack, get all your men up here in front of my men." Jack called his men .together. They did it, eyeing the soldiers closely. Some of the old men were saying, "Maybe this man wants to repeat what Ben Wright did to us Modocs years ago." When all the Modocs got in front of Jackson and his soldiers, Jackson says to Capt. Jack: "Now, Jack, lay down your gun here," pointing to a bunch of sage-brush. Jack hesitated. At last Jack says: "What for?" Jackson told him, "You are the chief. You lay your gun down, all your men does the same. You do that, we will not have any trouble." "Why do you want to disarm me and my men for? I never have fought white people yet, and I do not want to. Some of my old men are scared of what you ask me to do." Jackson said : "It is good, Jack, that you do not want to fight whites. If you believe what you say, Jack, and you will give up your gun, I won't let anyone hurt you." Jack looked at his own men and ordered them to lay down their guns. Every Indian stepped up smiling, and laid down his trusty muzzle-loading rifle. Scar-Face Charley laid his gun down on top of the pile of guns the Indians had stacked, but he kept his old revolver strapped on. Jackson ordered him to take his pistol off and hand it over. Scar-Face said: "You got my gun. This pistol all lite. Me no shoot him you." Jackson ordered his lieutenant, Boutelle, to disarm Scar-Face, whereupon Lieutenant Boutelle stepped forward

and said: "Here, Injun, give that pistol here, d m you,

quick." Scar-Face Charley laughed and said : "Me no dog. Me man. Me no fraid you. You talk to me I just like dog. Me no dog. Talk me good. I listen you." Boutelle drew his

revolver, saying, "You son - - b , I will show you now

to talk back to me." Scar-Face said, "Me no dog. You no shoot me. Me keep pistol. You no get him, my pistol." Boutelle leveled his revolver at Scar-Face's breast. Scar-Face drew his pistol. At the same instant, both pistols made but one report. The Indian's bullet went through Boutelle's coat sleeve. Scar-Face jumped and got his gun. .Every Indian then followed suit. The soldiers opened fire on the Indians.

Not more than thirty feet from them, the Indians piled on one

another, trying to get their guns. After the Indians got their

guns they gave battle. The soldiers retreated after a few

minutes of firing, leaving one dead and seven severely

wounded on the field. The Modocs lost one warrior killed and

about half a dozen wounded. The Modoc warrior killed was

known as Watchman; his Indian name was Wish-in-push.*

When the Indians saw that their comrades on the south bank was into it, they jumped in their dugouts to go across and assist in the fight. When they were about in the middle of the river, the settlers on the north bank fired on them. George Faiuke fired the first shot, saying: "Up at them, boys!" The Indians returned the fire from their dugouts. They turned around and paddled back to the north side. By the time the Indians got on the bank the settlers were way back in the thick, tall sage-brush, shooting all the time with but little effect, only killing one old squaw on the north side, killed one little baby, shot out of its mother's arms while she was running to get in the thick tules. One man had his arm broken. His name w r as Duffey. 1 On the white side three men w T ere killed. On the south side one able-bodied warrior was killed ; one girl about fifteen years old killed ; two small

- "Major Jackson finally rode over to me and said, 'Mr. Boutelle, what do

you think of the situation?' 'There is going to be a fight,' I replied, 'and the sooner you open it the better, before there are any more complete prepara- tions.' He then ordered me to take some men and arrest Scarface Charley and his followers. I had taken the situation in pretty thoroughly in my mind and knew that an attempt to arrest meant the killing of more men than could be spared, if any of the survivors were to escape. I was standing in front of the troop. I called out to the men, 'Shoot over those Indians,' and raised my pistol and fired at Scarface Charley. Great minds appear to have thought alike. At the same instant, Oharley raised his rifle and fired at me. We both missed, his shot passing through my clothing over my elbow. It cut two holes through my blouse, one long slit in a cardigan jacket, and missed my inner shirts. My pistol bullet passed through a red handkerchief Charley had tied around his head, so he afterwards told me. Thefe was some discussion after the close of the war, as to who fired the first shot. I use a pistol in my left hand. The track of Scarface Charley's bullet showed my arm was bent in the act of firing, when he fired. We talked the matter over, but neither could tell which fired first. The fight at once became gen- eral. Shots came from everywhere, from the mouth of the tepees, from the sage brush on our left, from the river bank and from the bunch of braves in which Scarface Charley was at work. As soon as I had time to see that I had missed, I suppose I fired another shot at Charley, at which he dropped and crawled off in the brush. Just then an Indian dropped on his knees in the opening of a tepee a few yards from our right front, and let slip an arrow at me. This I dodged and the subsequent proceedings interested him

(This is Major F. A. Boutelle' s version of the affair with Scarface Char- ley, as written by him for Cyrus Townsend Brady's book entitled, "Northwest Fights and Fighters," from pages 266 and 267.)

Major Boutelle now resides in Seattle. Major Jackson resides in Portland. iDuffey was the father of Watson Duffey, who resides near the author's place. He died at the Yainax, Oregon, on the 19th day of December, 1897.

OP THE MODOC WAR

children killed; one old woman, helpless, very old, burned up; Skukum Horse shot below the right nipple, making a bad wound.

After the Indians repulsed the soldiers, the women took to their dugouts, many going along the river through the titles, towards the lake on foot. Some of them hid right close to their camp so they could leave under cover of darkness the fol- owing night. The warriors got together, some on both sides of the river. The older men started right for the Lava Beds, and quite a few of the women and children in their dugouts or canoes. The Indians on the north bank of Lost River col- lected together and decided to kill the settlers. The settlers had all gone home. About ten o'clock a. m. Hooker Jim led the Indians on to the settlers' homes. By sundown Hooker Jim and his men had killed eighteen settlers, but they never touched a white woman or a child. Bogus Charley told Mrs. Boddy that she need not be afraid of him. He said this just as Mrs. Boddy used to tell it. "Don't be afraid, Mrs. Boddy, we won't hurt you. We're not soldiers. We men never fight white women ; never fight white girl, or baby. Will kill you women's men, you bet. Soldier kill our women, gal, baby, too. We no do that. All I want is something to eat. You give, I go. Maybe I see white man; I like kill him. No like kill white woman." She said she gave him flour, sugar, and coffee. He thanked her and went on his mission of killing.

Kind reader, would these settlers have been killed if they had stayed at their homes as they were requested to do by the Indians? No, sir. The settlers would never have been bothered, not a bit more than their wives were. The Modocs never harmed one child or woman since Capt. Jack became a chief. Major Jackson's soldiers shot down women and chil- dren in Jack's village. Mind, kind reader, these men that shot the squaws and children were white men, government soldiers, supposed to be civilized. Jack, a born savage, would not allow his men to do such a coward's work, as he called it.

When the soldiers saw that the Indians had all left their village along in the afternoon, they went back to see after their dead. The soldier boys found a very old sq uaw. She

was so old she could not walk, was blind, could not see. The soldiers took title matts and heaped them up on the old squaw till they got a big pile heaped on her, say like a load of straw. One of the boys lit a match and set the pile of tule matts on fire that they had heaped on that poor old helpless blind squaw and burned her up alive. After the matts burned up, the body

One-TCytd Mose, a Modoc warrior. Indian name Mose Ki -e.sk. Husband of One-Eyed Dixie. Died near Bly, Oregon, 1010. Cousin to Capt. Jack. Photo by Mr. Heller, 1873. From the Collection of Mr. John Daggett.

of the old squaw was laying drawn up burned to a crisp. One of the officers saw her. He said : "Boys, kick some sand over that old thing. It looks too bad !" Mind you, gentle reader, this happened right under the eyes of the officers of this United States government that was in command that twenty-ninth day of November, 1872.

I can write many and many such doings on the white's

side. It was not the Indians altogether that did the dark

deeds that happened in early days in the West. The people

at large never got the Indian side of any of the Indian wars

with the white people of the United States, although some

tribes did some a\vful bad deeds. On the other hand, the

white people did the same. The Modoc Indians never killed

white women or children after Capt. Jack became chief of the

Modocs. Jack would never allow such doings.

One-Eyed Dixie, a Modoc squaw and survivor, now residing at the Snake Camp, near the Yainax, Klamath Reservation, Oregon. Photo by Mr. Heller, 1873. From the Collection of Mr. John Daggett.

CHAPTER VI.

Captain Jack and his people all arrive safe in the Lava Beds. Captain Jack occupies the largest cave, known nowadays as Captain Jack's Stronghold. Indians all live in different caves. They make prep- arations for war.

After the Modocs all got well settled in the Lava Beds they took life easy for about two weeks, keeping two men on guard night and day. They did not intend to be caught nap- ping. They was expecting troops all the time. About mid- day, January 15, 1873, one of the Modoc guards saw a large body of horsemen about two miles west of their camp on a ridge. He reported to his chief. The chief ordered his men to prepare for battle. The enemy disappeared. The men that appeared on the ridge, was a company that was out on a scout- ing expedition, sent out by General Gillem, from John Fair- child's ranch near Hot Creek, California.

General Gillem had his headquarters at Fairchild's ranch. He had about two hundred soldiers under his command at that time. The scouting party returned to Gillem s headquar- ters late in the evening of the 1 5th and reported to the general that they had located the Indian camp. The general ordered a company of cavalrymen on the morning of the i6th to ad- vance on the Indians and rout them out of the Lava Beds, and chase them if they could get them started. Spare none. The troops started for the field of action, early morning of the 1 6th. They arrived at the foot of the hill on the south- west of the Tule Lake edge of the Lava Beds in the afternoon. The troops camped there for the night about one mile and a half from the stronghold. Before sundown a company of Oregon volunteers and some twenty or thirty Klamath Indians arrived, also made their camp alongside of the soldiers. The soldiers and volunteers put their guards out, two hundred yards from the camp.

The men after supper sat around their campfires, all dis- cussing the events of tomorrow, how they were going to whip

the Indians. One volunteer says to his comrade : "Say, Jim,

The Fairchild Ranch on Cottonwood Creek, near Dorris, Siskiyou County, California. Founded by the late Judge J. A. Fairchild. This is where some of the Modoc Warriors surrendered.

By the kindness of the present owner, Mr. J. P. Churchill of Yreka, Cal.

M ?

how are you going to eat your Modoc sirloin for dinner to- morrow, raw or cooked? I am going to eat mine raw. I don't want to take the time to cook it. I want to clean 'em all up before I stop, the red devils." Jim replied : "Bill, gol darn it, I don't like the idea of facing these red devils. I wish I had stayed at home. I believe, Bill, these reds are going to be hell; gol darn it, I do. I heard these Modocs was gol darn good shots; darn it, I don't want 'em to shoot at me. "Say, Jim, play sick in the morning. You won't have to go out to face 'em at all; you are afraid of them Injuns; Jim, I'll go, and I will bring some Modoc steak in for you tomorrow evening." "Bill, gol darn it, don't talk about them Injuns. They are bad medicine; gol darn it, they be." Some of the volunteers were going to capture nice looking Indian maids and make them cook the company's meals.

One of the volunteer's beats was right on the shore of the lake. He was on the lookout for the Indians pretty close for a short time. He got sleepy and did not pay much attention to his duty. The moon came up. The volunteer noticed the moon and stopped and rubbed his eyes. He yawned and was just in the act of starting again on his beat. All at once he saw his own shadow in the lake. He levelled his gun at his shadow and fired, and at the same time he yelled like ten Modoc war- riors. The camp was in commotion. They thought the whole Modoc nation was right in amongst them. Some of the volunteers broke for the hill like escaped horses. Some of them tucked their blankets close over their heads and imagined themselves safe from the Modoc bullets. They soon found out that the guard had been dreaming. The guard told them that he had seen the Injun swimming right up to him with his gun in his teeth. "I shot the devil. He sunk right where I shot him." Some of the boys next morning went down to where the guard had killed the Injun, but found the water only ten inches deep. They concluded that the guard did not kill any Indians. The boys teased the Indian-killer so much about him shooting at his own shadow, he pulled his coat off

and said: "He could lick any mother's son in the compa

Showing the place where the Peace Commissioners were killed.