PART II

ABDICATION

I

LOVE

I'me la morte, in te la vita mia.[1]

After renouncing everything which kept him alive, a new life—like the spring which blossoms again—sprang up in Michael Angelo's devastated heart, and love burnt with a brighter flame. But it was a form of love in which there was hardly a trace of either egoism or sensuality. It consisted in the mystical adoration of the beauty of a Cavalieri, in the religious friendship of Vittoria Colonna—the passionate communion of two souls in God. It consisted, also, in paternal tenderness for his orphan nephews, in pity for the poor and the weak, and in holy charity.

Michael Angelo's love for Tommaso dei Cavalieri is calculated to disconcert the minds of many, whether honest or dishonest. Even in the Italy of the closing days of the Renaissance it gave rise to unpleasant interpretations, and Aretino made outrageous allusions to it.[2] But the insults of an Aretino—such men are common to all ages—could not reach a Michael Angelo. "They formed in their hearts a Michelagniolo out of the stuff of which their own hearts was made."[3]

No one possessed a purer soul than Michael Angelo. No one had a more religious conception of love. "I have often heard him speak of love," says Condivi, "and those who were present used to say that Plato did not speak otherwise. For my part, I know not what Plato said of it; but this I know well, in my long and intimate intercourse with him, I have never heard him utter any but the most honourable words, which had the effect of calming in young men the inordinate desires which agitated them."

But there was nothing literary and cold in this Platonic idealism: it was united to a frenzy of thought which made Michael Angelo the prey of everything which he considered beautiful. He knew this himself, and said one day when refusing an invitation from his friend Giannotti:

CHRIST CONDEMNING THE WICKED

Fragments of "The Last Judgment," in the Sistine Chapel

If he were thus overcome by beauty of thoughts, words or sounds, how much more so must he have been by bodily beauty!

"La forza d’un bel visio a che mi sprona!

C’altro non è c’ al mondo mi dilecti …"[5]

To this great creator of admirable forms, and who at the same time was a great believer, a beautiful body was divine—a beautiful body was God Himself appearing under the veil of the flesh. Like Moses before the Burning Bush, he trembled on approaching. The object of his adoration was to him truly an idol, as he himself said. He threw himself at its feet; and this voluntary humiliation of a great man, which was painful to the noble Cavalieri himself, was all the more strange because the idol with the beautiful face was often a vulgar and despicable being like Febo di Poggio. But Michael Angelo saw nothing of this … Did he really see nothing? He had no desire to see anything; he was completing in his heart the statue he had rough-hewn.

The earliest of these ideal lovers, of these living dreams, was Gherardo Perini, whose acquainance with the sculptor dates from about 1522.[6]

Later, in 1533, Michael Angelo became enamoured of Febo di Poggio, and in 1544 it was the turn of Cecchino dei Bracci.[7] His friendship for Cavalieri was not, therefore, exclusive and unique. But it was durable, and it reached a height which, to a certain extent, was justified not only by the friend’s beauty but by his moral nobility.

"Far above all others, without comparison," says Vasari, "he loved Tommaso dei Cavalieri, a Roman noble, a young man devoted to art … Michael Angelo drew a life-size portrait of him, his first and last, for he abhorred drawing anything that was not of the utmost beauty."

Varchi adds:

"When I saw Messer Tommaso Cavalieri at Rome he was not only of incomparable beauty but possessed such grace of manner, such a distinguished mind and such nobility of conduct that he well merited being loved, and all the more so as one got to know him."[8]

Michael Angelo met him in Rome in the autumn of 1532. The first letter in which Cavalieri replies to Michael Angelo’s impassioned declarations is full of dignity:

"I have received a letter from you, which has been all the dearer to me because it was unexpected. I say unexpected because I do not consider myself sufficiently worthy to be written to by a man such as you. As to what you have said in my praise, and as to these works of mine, for which you assure me you have felt no small sympathy, I reply that they were not of a nature to warrant a man with a genius like yours—a genius such as is, I will not say without a parallel, but without a rival upon earth—to write to a young man who has barely made his début and who is so ignorant. I cannot believe, however, that you lie. I believe, yes, I am certain, that the affection which you show me has no other cause than the love that a man like you, who is the personification of art, must necessarily have for those who devote themselves to art and love it. I am one of those, and as regards love of art I give place to no one. I amply return your affection—that I promise you. Never have I loved a man more than you, never have I desired a friendship more than yours ... I beg you to make use of me, should an opportunity offer, and eternally recommend myself to you.

Cavalieri seems to have ever maintained this tone of respectful and reserved affection. He remained faithful to Michael Angelo until his last hour, at which he was present. He retained his confidence; he was the only one who was reputed to have any influence over him, and he possessed the rare merit of having always used it for his friend's benefit and grandeur. He it was who made Michael Angelo decide to complete the wooden model of the cupola of St. Peter's. He it was who preserved Michael Angelo's plans for the construction of the Capitol, and who worked at their realisation. He it was, finally, who, after the death of the sculptor, saw that his wishes were carried out.

But Michael Angelo's friendship for him resembled the passion of love. He wrote him frenzied letters: addressed his idol with his head bowed down to the dust.[10] He called him "a powerful genius . . . a miracle . . . . the light of our century"; he implored him "not to despise him, because he could not compare himself to him—he who was without an equal!" He laid the whole of his present and the whole of his future at his feet, and added:

"It is an infinite sorrow to me not to be able to give you my past also, in order to serve you all the longer. For the future will be short. I am too old. . . .[11] I do not believe that anything can destroy our friendship, although I speak in a very presumptuous fashion, for I am infinitely beneath you. . . .[12] I could as easily forget your name as the nourishment on which I live; yes, I could as easily forget the nourishment on which I live, and which only sustains the body, without pleasure, as your name, which nourishes the body and the soul, and fills them with such sweetness that as long as I think of you I feel neither suffering nor the fear of death.[13] My soul is in the hands of the one to whom I have given it. . . .[14] If I were to cease thinking of him I believe that I should fall dead on the spot."[15]

He made superb presents to Cavalieri:

"Stupendous designs and heads in black and red chalk, which he had made with the intention of teaching him how to draw. Then he drew for him a Rape of Ganymede, the Vulture eating the Heart of Tityrus, the Fall of the Chariot of the Sun in the Po, and a Bacchanalia of Infants, all most rare and unique."[16]

He also sent him sonnets, sometimes admirable, often obscure, and some of which were soon recited in literary circles and known all over Italy.[17] The following sonnet has been styled "the finest lyric poem that Italy produced in the sixteenth century":[18]

"With your beautiful eyes I see a gentle light, which my blind eyes can see no longer. Your feet assist me to bear a load which my crippled feet can support no longer. I feel that, through your mind, I am raised to heaven. My will is centred in your will. My thoughts are formed in your heart and my words in your breath. Abandoned to myself, I am like the moon, which is invisible in the sky as long as the sun shines.[19]

Still more celebrated is this other sonnet, one of the finest poems which has ever been written in honour of perfect friendship:

"If a chaste love, if a superior devotion, if an equal fortune exist between two lovers, if cruel fate in striking one strikes the other, if a single mind, if a single will governs two hearts, if a soul in two bodies has become eternal, bearing both to heaven on the same wings, if Cupid with a single golden shaft pierces and burns the heart of both at once, if one loves the other and neither loves himself, if both centre their pleasure and their joy in attaining the same end, if a thousand thousand loves are not a hundredth part of the love and faith which binds them, could a movement of vexation ever shatter and untie such a bond?"[20]

This forgetfulness of self, this ardent gift of his whole being, which melted in that of the beloved one, was not always characterised by this serenity. Sadness once more got the upper hand, and the soul, possessed by love, struggled and moaned.

"I weep, I burn, I am consumed, and my heart nourishes itself on its troubles…."[21]

"You who have taken from me the joy of living," he says elsewhere to Cavalieri.[22]

To these over-passionate poems, Cavalieri, "the gentle and beloved lord,"[23] opposed his calm and affectionate coldness.[24] Secretly he was shocked by the exaggeration of this friendship. Michael Angelo made excuses:

"My dear lord, do not be irritated by my love, which is addressed only to what is best in you,[25] For the spirit of the one ought to be enamoured of the spirit of the other. That which I desire, that which I learn in your beautiful face, cannot be understood by ordinary men. He who wishes to understand it must first of all die."[26]

And certainly there was nothing immodest in this passion for beauty.[27] But the secret of this ardent and agitated love [28] (yet for all that chaste) was nevertheless disquieting and deluded.

To these morbid friendships—a despairing effort to deny the nothingness of his life and create the love for which he craved—there fortunately succeeded the serene affection of a woman, who could understand his old child, alone and lost in the world, and bring to his bruised soul a little peace, a little confidence, a little reason, and melancholy acceptance of life and death.

It was in 1533 and 1534[29] that Michael Angelo's friendship for Cavalieri reached its height. In 1535 he began to know Vittoria Colonna.

She was born in 1492. Her father was Fabrizio Colonna, Lord of Paliano and Prince of Tagliacozzo.

YOUNG WOMAN WEARING A HELMET

From the drawing in the Uffizi Gallery

She did, in fact, suffer cruelly through the infidelity of her husband, who deceived her in his own house to the knowledge and in the sight of all Naples. Nevertheless, on his death in 1525, she was inconsolable. She sought refuge in religion and poetry. She led a claustral life, first at Rome, then in Naples,[32] but without renouncing in the early days thoughts of the world. She sought solitude merely in order to be able to absorb herself in the recollection of her love and celebrate it in verse. She was in relations with all the great writers of Italy—with Sadoleto, Bembo, and Castiglione, who entrusted the manuscript of his "Cortegiano" to her; with Ariosto, who celebrated her in his "Orlando"; with Paul Jove, Bernardo Tasso and Lodovico Dolce. From 1530 her sonnets were read over the whole of Italy and secured her a position of unique glory among the women of her period. Having retired to Ischia, she was indefatigable, in the solitude of the beautiful island and amidst the harmonious sea, in singing of her transfigured love.

But from 1534 religion occupied her entire attention. The spirit of Catholic reform—the free religious spirit which then tended to regenerate the Church without running the risk of a schism—took possession of her. Whether she knew Juan de Valdès[33] in Naples is unknown, but she was overwhelmed by the sermons of Bernardino Ochino of Sienna;[34] she was the friend of Pietro Carnesecchi,[35] Giberti, Sadoleto, the noble Reginald Pole, and of the greatest of these reforming prelates, who constituted in 1536 the Collegium de emendandâ Ecclesiâ—namely, Cardinal Gaspare Contarini,[36] who tried in vain, at the Diet of Ratisbonne, to establish unity with the Protestants, and who dared to write these strong words:[37]

"The law of Christ is a law of liberty. … One cannot call by the name of government that the rule of which is the will of a man, inclined by nature to evil and impelled by innumerable passions. No! Every sovereignty is a sovereignty of reason. Its object is to lead those who are under its sway to their just goal—happiness—and by paths that are just. The authority of the Pope is also an authority of reason. A Pope should know that he exercises his authority over free men. He ought not to command, or defend, or dispense of his own will, but only in accordance with the rules of reason, the divine Commandments and Love—a rule which leads back everything to God and the common good."

Vittoria was one of the most exalted souls of this little idealistic group, which united the purest consciences of Italy. She corresponded with Renee of Ferrare and Margaret of Navarre; and Pier Paolo Vergerio, later a Protestant, called her "one of the lights of truth." But when the counter-reform movement began, under the direction of the merciless Caraffa,"[38] she fell into mortal doubt. Like Michael Angelo, she had a passionate but weak soul: she felt a need to believe; she was incapable of resisting the authority of the Church. "She tortured herself by fasts and hair-shirts until she was nothing more than flesh and bone."[39] Her friend Cardinal Pole[40] restored her peace of mind by forcing her to submit, to humiliate the pride of her intelligence, to forget herself in God. She did so in a wild moment of sacrifice. … Ah! if she had only sacrificed herself! But she sacrificed her friends with her: she disowned Ochino, whose writings she delivered over to the Inquisition of Rome. Like Michael Angelo, her great soul was shattered by fear. She drowned her remorse in despairing mysticism.

"You have witnessed the chaos of ignorance in which I was," she wrote; "the labyrinth of errors in which I wandered, my body perpetually in movement to find repose and my soul ever agitated in its search for peace. God has willed that I should be told Fiat lux! and that I should be shown that I am nothing—that everything is in Christ!"[41]

She welcomed death as a deliverance. She died on February 25, 1547.

It was at the time she was most profoundly penetrated by the free mysticism of Valdès and Ochino that she made Michael Angelo’s acquaintance. This woman, sad and tormented, who had ever need of a guide on whom to lean, had no less need of a weaker and more unfortunate being than herself on whom to expend the maternal love with which her heart was full. She endeavoured to hide her trouble from Michael Angelo. Serene in appearance, reserved, somewhat cold, she transmitted to him the peace which she demanded from others. Their friendship, which began about 1535, was intimate from the autumn of 1538, and entirely based on God. Vittoria was forty-six years of age; he was sixty-three. She lived in Rome, at the cloisters of San Silvestro in Capite, below Monte-Pincio. Michael Angelo lived near Monte Cavallo. They met on Sundays in the Church of San Silvestro on Monte Cavallo. Friar Ambrogio Caterino Politi read to them the Epistles of St. Paul, which they discussed together. The Portuguese painter, Francis of Holland, has handed down to us the recollection of these conversations in his four "Dialogues on Painting."[42] They form a living picture of this grave and tender friendship.

The first time that Francis of Holland went to the Church of San Silvestro he found the Marchesa di Pescara there with a few friends, listening to the holy word. Michael Angelo was not of the company. When the Epistle was finished the amiable woman said to the stranger, with a smile:

"Francis of Holland would doubtless have more willingly heard a discourse of Michael Angelo than this sermon."

To which Francis—stupidly offended—replied:

"Indeed, Madame? Does it seem to your Excellency that I have sense for nothing else and am only good for painting?"

"Do not be so susceptible, Messer Francesco," said Lattanzio Tolomei. "The Marchesa is quite convinced that a painter is good for everything. So much do we Italians esteem painting! But perhaps she said that merely to add to the pleasure which you have had—that of hearing Michael Angelo."

Francis was then lost in apologies, and the Marchesa said to one of her servants:

"Go to Michael Angelo's and tell him that Messer Lattanzio and I have remained, after the close of the religious service, in this chapel, where it is agreeably cool. If he would consent to lose a little of his time,

we should profit greatly. . . . But," she added, knowing Michael Angelo's unsociableness, "do not tell him that the Spaniard Francis of Holland is here."

Awaiting the servant's return they fell into conversation, endeavouring to find out by what means they could lead Michael Angelo to speak on the subject of painting, but without him suspecting their intention, for, if he perceived it, he would immediately refuse to continue the conversation.

"There was a brief silence. A knock came at the door. We all expressed a fear, since the reply had come so promptly, that it could not be the master. But my star willed that Michael Angelo, who lived quite near, should at that very time be on his way in the direction of San Silvestro; he was proceeding along the Via Esquilina, towards the Thermtæ, philosophising as he went with his disciple Urbino. And as our envoy had met him and brought him along, he it was who stood upon the threshold. The Marchesa rose and long remained in conversation with him, standing and apart from the others, before she invited him to take a seat between Lattanzio and herself."

Francis of Holland sat by his side. But Michael Angelo paid not the slightest attention to him. Whereupon the Spaniard was acutely nettled and said, with a vexed air:

"Verily the surest means of not being seen by any one is to place oneself right in front of his eyes!"

Michael Angelo, astonished, looked at him and immediately apologised, with great courtesy.

"Pardon me, Messer Francesco," he said. "In truth I did not notice you, for all my attention was centred on the Marchesa.

"Meanwhile Vittoria, after a slight pause, began, with an art which is deserving of the highest praise, to speak, adroitly and discreetly, of a thousand things, but without touching on the subject of painting. It was like one who lays siege, with difficulty and with art, to a fortified town. And Michael Angelo had the air of a besieged person who, vigilant and defiant, puts guards here, raises bridges there, places mines elsewhere, and keeps the garrison on the alert at the gates and on the walls. But finally the Marchesa carried the day. And truly no one could defend himself against her.

"Well," said she, "we must indeed recognise that we are always conquered when we attack Michael Angelo with his own arms, that is to say with cunning. We must speak to him, Messer Lattanzio, on the subject of lawsuits, papal briefs, or else . . . painting if we would reduce him to silence and have the last word."

This ingenious détour led the conversation on to the subject of art. Vittoria informed Michael Angelo of a religious construction which she proposed to raise, and immediately Michael Angelo offered to examine the site and draw up a plan.

"I should never have dared to ask so great a service," replied the Marchesa, "although I know that in everything you follow the teachings of the Lord, who lowers the haughty and raises up the humble. . . . Consequently, those who know you esteem the person of Michael Angelo much more than his works, whilst those who do not know you personally glorify the weakest part of yourself—that is to say, the work of your hands. But I praise you no less for so often withdrawing aside, fleeing from our useless conversations, and, instead of painting all the princes who come to beg you to do their portraits, for devoting almost the whole of your life to a single great work."

Michael Angelo modestly declined these compliments, and expressed his aversion for chatterers and idlers—whether great lords or popes—who thought it permissible to impose their society on an artist, when even now his life was not long enough to enable him to accomplish his task.

The conversation then passed to the highest artistic subjects, which the Marchesa treated with religious gravity. In her opinion, as in that of Michael Angolo, a work of art was an act of faith.

"Good painting," said Michael Angelo, "approaches God and is united with Him. ... It is but a copy of His perfection, a shadow of His brush. His music. His melody. . . . Consequently, it is not sufficient for a painter to be merely a great and skilful master. I think that his life must also be pure and holy as much as possible, in order that the Holy Spirit may govern his thoughts."[43]

And thus the day wore on, with these truly sacred and majestically serene conversations in the Church of San Silvestro, unless the friends preferred to continue them in the garden—which Francis of Holland describes for us: "near the fountain, within the shade of laurel bushes, seated on a stone bench placed against an ivy-covered wall," whence they looked down on Rome stretched at their feet.[44]

Unfortunately these beautiful conversations did not last. They were suddenly interrupted by the religious crisis through which the Marchesa di Pescara was passing. In 1541 she left Rome to shut herself up in a cloister, first at Orvieto and then at Viterbo.

"But she often set off from Viterbo and came to Rome, specially to see Michael Angelo. He was enamoured of her divine spirit, and she amply returned his admiration. He received from her and kept many letters, full of a chaste and very gentle love, and such as that noble soul could write."[45]

"At her request," adds Condivi, "he executed a nude Christ, who, detached from the Cross, would have fallen like a dead body at the feet of his Holy Mother had not two angels supported Him by the arms. Mary is seated under the Cross; her face is marked by tears and suffering; and with open arms she raises her hands heavenwards. On the wood of the Cross we read the words: 'Non vi si pensa quanto sangue costa.'[46] For love of Vittoria, Michael Angelo also drew a Christ on the Cross, but not dead, as He is usually represented, but living, with His face turned towards His Father, and crying: 'Eli! Eli!' The body does not willingly abandon itself; it twists and contracts in the last sufferings of death."

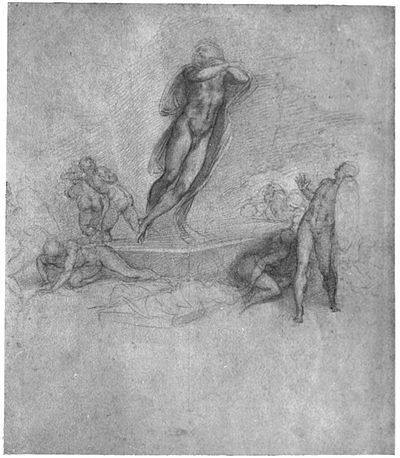

THE RESURRECTION

From a drawing in the Louvre

Thus did Vittoria reopen the world of faith to the art of Michael Angelo. She did still more—she gave free scope to that poetic genius which his love for Cavalieri had awakened.[47] Not only did she enlighten him as regards religous revelations, of which he had a dim presentiment, but, as Thode has shown, she set him the example of singing them in her verses. It was during the early days of their friendship that the first “Spiritual Sonnets” of Vittoria appeared.[48] She sent them to her friend as soon as she had written them.[49]

He found a consolatory charm, a new life in them. A beautiful sonnet which he addressed to her in reply bears witness to his tender gratitude:

“Blessed spirit who, by your ardent love, keeps my old heart, so near the point of death, alive, and who, in the midst of your possessions and your pleasures, distinguish me alone among so many nobler beings—so you appeared formerly to my eyes, so now, in order to console me, you show yourself to my soul. … That is the reason why, receiving this favour from you, who think of me in my troubles, I write to thank you. For it would be a piece of great presumption and a great shame if I offered to give you wretched paintings in exchange for your beautiful and living creations."[50]

In the summer of 1544 Vittoria returned to live in Rome, in the cloisters of Santa Anna, and she remained there until her death. Michael Angelo used to go to see her. She thought affectionately of him, tried to put a little pleasure and comfort into his life, and, secretly, to make him a few little presents. But the suspicious old man, "who would accept presents from no one,"[51] even from those whom he loved the most, refused to give her this pleasure.

She died. He saw her die, and he uttered these touching words, which show with what a chaste reserve their great love had been surrounded:

"Nothing distresses me more than to think that I have seen her dead, and that I have not kissed her forehead and her face as I have kissed her hand."[52]

"This death," says Condivi, "made him for a long time quite stupid: he seemed to have lost his intelligence."

"She wished me the greatest good," said Michael Angelo sadly, later on, "and I the same (Mi noleva grandissimo bene, e io non meno di lei). Death has robbed me of a great friend."

He wrote two sonnets on this death. One, imbued with the Platonic spirit, is characterised by a rugged affectation and a deluded idealism: it is comparable to night with lightning flashing across the sky. Michael Angelo compares Vittoria to the hammer of the divine sculptor, who makes his sublime thoughts spring forth from matter.

"If my rude hammer fashions hard rocks first into one image and then into another, it is from the hand which holds and guides it that it receives movement; it acts through the influence of a foreign force. But the divine hammer which is raised in the heavens creates its own beauty and the beauty of others by reason of its own strength. No other hammer can create without this hammer; this one alone gives life to all the others. And since the blow which it strikes on the anvil is so much the greater the higher it is raised in the forge, this hammer has risen above me to heaven. That is why it will guide my work to a good end, if the divine forge lends its aid. Up to now, on earth, it was alone."[53]

The other sonnet is more tender and proclaims the victory of love over death.

"When she who drew from my breast so many sighs slipped away from the world, from my eyes and from herself. Nature which had judged us worthy of her

THE RESURRECTION

From a drawing in the British Museum

It was during this grave and serene friendship[55] that Michael Angelo executed his last great works in painting and sculpture: “The Last Judgment,” the frescoes of the Pauline Chapel and—at last—the mausoleum of Julius II. When Michael Angelo left Florence in 1534 to settle down in Rome he thought that, having been relieved of all his other works by the death of Clement VII., he would be able to complete the mausoleum of Julius II. in peace, and then die, with his conscience relieved of the burden which had weighed on the whole of his life. But he had hardly arrived than he allowed himself to be enchained by new masters.

“Paul III. soon summoned him and required his services. … Michael Angelo, however, declined until the tomb should be finished, alleging his contract with the Duke of Urbino. His refusal angered the Pope, who said, ‘I have been longing for this opportunity for thirty years, and shall I not have it now I am Pope? I will tear up the contract, and I am determined that you shall serve me, come what may.’”[56]

Michael Angelo was on the point of fleeing.

“He thought of taking refuge near Genoa, in an abbey of the Bishop of Aleria, who was his friend and who had been that of Julius II. There, in the neighbourhood of Carrara, he would comfortably have finished his work. He was also struck with the idea of retiring to Urbino, a peaceful spot, where he hoped that, out of respect for the memory of Julius II., he would be well received. With that object in view he had already sent there one of his men to buy a house."[57]

But, at the moment of coming to a decision, his willpower, as usual, failed him; he feared the consequences of his acts, and deceived himself with the eternal illusion—inevitably ending in disappointment—that he could get out of the difficulty by some compromise or other. He again allowed himself to be enchained and continued to drag his cannon ball until the end.

On September 1, 1535, Paul III. issued a brief appointing him architect-in-chief, sculptor and painter to the apostolic palace. Since the preceding April Michael Angelo had consented to work on "The Last Judgment."[58] He was entirely occupied with this work from April 1536 to November 1541—that is to say, during the sojourn of Vittoria at Rome. In the course of this enormous task—doubtless in 1539—the old man fell from his scaffolding and seriously injured his leg. "In his pain and anger he refused to be attended by a doctor."[59] He detested doctors and manifested in his letters a comical anxiety on hearing that one of the members of his family had had the imprudence to call one in.

"Fortunately for him, after his fall. Maestro Baccio Rontini, a Florentine, his friend and a clever physician, who loved the arts, took compassion on him and went to his house. When no one answered his knock he entered by a secret way, and passing from room to room found Michael Angelo in desperate case. Baccio refused to leave him before he was healed.”[60]

As Julius II. had formerly done, Paul III. used to come to see Michael Angelo painting, and gave his opinion. He was accompanied by his master of the ceremonies, Biagio da Cesena. One day the Pope asked this official what he thought of the work. Biagio, who, says Vasari, was a very scrupulous person, declared that it was “a disgrace to have put so many nudes in such a place, and that the painting was better suited to a bathing-place or an inn than a chapel. This angered Michael Angelo, so, after they had gone, he drew a portrait of Biagio from memory, representing him as Minos in Hell among a troop of devils, with a great serpent wound about his legs.” Biagio complained to the Pope. But Paul III. laughed at him. “Had Michael Angelo put you in Purgatory,” he said to him, “there might have been some remedy, but from Hell, ‘Nulla est redemption.’”

CHARON'S BOAT

Fragment of "The Last Judgment" in the Sistine Chapel

When the Sistine fresco was completed,[69] Michael Angelo thought that at last he had the right to finish the monument of Julius II. But the insatiable Pope demanded that the old man of seventy should paint the frescoes of the Pauline Chapel.[70] He almost put his hand on some of the statues intended for the tomb of Julius II. in order to use them for the ornamentation of his own chapel! Michael Angelo had to consider himself fortunate in being allowed to sign a fifth and last contract with the heirs of Julius II.—a contract by which he agreed to deliver his completed statues[71] and pay two sculptors to finish the monument, after which he was released from any other obligation for ever.

But he was not at the end of his troubles. The heirs of Julius II. continued greedily to claim the money which they alleged had formerly been laid out for him. The Pope told him not to think about it, but to concentrate all his attention on the Pauline Chapel.

"But," replied Michael Angelo, "we paint with our head, not with our hands. He whose mind is not at ease dishonours himself. That is why, so long as I have these worries, I do nothing good. . . . I have been chained to this tomb the whole of my life. I have wasted all my youth in endeavouring to justify myself before Leo X. and Clement VII. I have been ruined by my too great conscientiousness. Thus did my fate ordain it! I see many men who have got together incomes of two to three thousand crowns, whilst I, after terrible efforts, have only succeeded in remaining poor. And they call me a thief! … Before men (I do not say before God) I consider myself an honest man. I have never deceived any one. . . . I am not a thief: I am a Florentine citizen, of noble birth, and the son of an honourable man. . . . When I have to defend myself against scoundrels I become, in the end, insane! . . . "[72]

In order to indemnify his adversaries he completed the statues representing "Active Life" and "Contemplative Life" with his own hand, although he was not forced to do so by his contract.

So, at last, in January 1545 the monument to Julius II. was inaugurated at San Pietro in Vincoli. What remained of the fine primitive plan? Only the statue of Moses, which became the centre of it, after having formerly been but one of its details. It was the caricature of a great project.

However, it was finished. Michael Angelo was delivered from the nightmare which had troubled the whole of his life.

MOSES (TOMB OF JULIUS II)

San Pietro in Vincoli, Rome

- ↑ "Poems," lix.

- ↑ Michael Angelo's great nephew, in the first edition of the Rime, in 1623, did not dare to publish the poems to Tommaso dei Cavalieri exactly. He left his readers to believe that they were addressed to a woman. Until the recent works of Scheffler and Symmonds, Cavalieri was regarded as an imaginary name, hiding the identity of Vittoria Colonna.

- ↑ Letter from Michael Angelo to an unknown person. (October 1542.) ("Letters," Milanesi's edition, cdxxxv.)

- ↑ Donato Giannotti's "Dialogi," 1545.

- ↑ "Poems," cxxxxi. "The strength of a beautiful face, what a spur it is to me! No other joy in the world is so great."

- ↑ Gherardo Perini was specially a mark for Aretino’s attacks. Frey publishes a few very tender letters of his, of 1522, in which we read such phrases as the following: "… Che avendo di voi lettera, mi paia chon esso voi essere, che altro desiderio non o." "When I have a letter from you, I seem to be with you, which is my unique desire." He signed himself: "Vostro come figliuolo," "Yours like a son." A beautiful poem by Michael Angelo on the sorrow of absence and forgetfulness seems to be addressed to him: "Quite near here my love has ravished my heart and life. Here, his beautiful eyes promised me their aid, and then withdrew it. Here he bound me; here he unbound me. Here I have wept, and, with infinite sorrow, I have seen, from this stone, depart the one who has taken me from myself, and who desires me no longer." (See Appendix, xi. "Poems," xxxv.)

- ↑ Henry Thode, who, in his work on "Michael Angelo und das Ende der Renaissance," cannot resist the desire of depicting his hero in the brightest colours, even sometimes at the expense of truth, places his friendship for Gherardo Perini and Febo di Poggio in such an order as to rise by degrees to his friendship for Tommaso dei Cavalieri, because he cannot admit that Michael Angelo could have descended from the most perfect love to the affection of a Febo. But, in reality, Michael Angelo had already been in relation with Cavalieri for more than a year when he became enamoured of Febo and wrote him the humble letters (of December 1533 according to Thode, or of September 1534 according to Frey) and the absurd and raving poems in which he plays upon the words Febo and Poggio (Frey, ciii., civ.)—letters and poems to which the young scamp replied by demands for money. (See Frey’s edition of the "Poems of Michael Angelo," p. 526.) As to Cecchino dei Bracci, the friend of his friend Luigi del Riccio, Michael Angelo did not know him until ten years after Cavalieri. Cecchino was the son of a banished Florentine, and died prematurely at Rome in 1544. In memory of him Michael Angelo wrote forty-eight funereal epigrams, full of idolatrous idealism, if one can use the phrase, and some of which are sublimely beautiful. These are perhaps the gloomiest poems which Michael Angelo ever wrote. (See Appendix, xii.)

- ↑ Benedetto Varchi’s "Due lezzioni," 1549.

- ↑ Letter from Tommaso dei Cavalieri to Michael Angelo. (January 1, 1533.)

- ↑ See especially the reply which Michael Angelo made to Cavalieri's first letter, on the very day on which he received it. (January 1, 1533.) There are three rough drafts of this letter, all feverish in their style. In a post-scriptum to one of them Michael Angelo writes: "It would be quite permissible to give the name of the thing which one man presents to another who receives it; but out of respect for propriety it does not appear in this letter." It is evident that the word in question was—love.

- ↑ Letter from Michael Angelo to Cavalieri (January 1, 1533).

- ↑ Rough draft of a letter from Michael Angelo to Cavalieri (July 28, 1533).

- ↑ Letter from Michael Angelo to Cavalieri (July 28, 1533).

- ↑ Letter from Michael Angelo to Bartolommeo Angiolini.

- ↑ Letter from Michael Angelo to Sebastiano del Piombo.

- ↑ Vasari.

- ↑ Varchi commented on two of them in public, and published them in his "Due Lezzioni." Michael Augelo made no secret of his love. He spoke of it to Bartolommeo Angiolini and Sebastiano del Piombo. No one was astonished at such friendships. When Cecchino del Bracci died, Riccio proclaimed his love and despair from the housetops. "Ah! friend Donato!" he said. "Our Cecchino is dead. All Rome is in tears. Michael Angelo is making the drawing of a monument for me. I beg you to compose an epitaph and send me a consoling letter. My mind is drowned in sorrow. Patience! Each hour I live with a thousand thousand dead! O God! how Fortune has changed her face!" (letter to Donato Giannotti, January 1544). "I bear a thousand souls of lovers in my breast," Michael Angelo makes Cecchino say in one of his funereal epigrams ("Poems," Frey's edition, lxxiii, 12).

- ↑ Scheffler.

- ↑ "Poems," cix, 19. {See Appendix, xiii.)

- ↑ "Poems," xliv. {See Appendix, xiv).

- ↑

"I' piango, i' ardo, i' mi consumo, c 'l core

Di questo si nutriscic….""Poems," lii. See also lxxvi. At the end of the sonnet Michael Angelo plays on Cavalieri's name, as follows:

"Resto prigion d'un Cavalier armato"

(I am the prisoner of an armed knight). - ↑ "Onde al mio viver lieto. che m'ha tolto…." "Poems," cix, 18.

- ↑ "Il desiato mie dolce signiore…" The same, I.

- ↑ "Un freddo aspetto…" The same, cix, 18.

- ↑ The exact text says: "That which you yourself love the best in yourself."

- ↑ See Appendix, xv.

- ↑ "Il foco onesto, che m'arde …" ("Poems," 1).

La casta voglia, che 'l cor dentro infiamma …" (The same, xliii).

- ↑ In a sonnet, Michael Angelo expressed a wish that his skin might serve to clothe the one he loved. He wished to be the shoes which covered his snow-like feet. (See Appendix, xvi.)

- ↑ Especially between June and October 1533, when Michael Angelo, having returned to Florence, was at a distance from Cavalieri.

- ↑ The beautiful portraits which are said to represent her are not authentic. Take, for instance, the celebrated drawing of the Uffizi, in which Michael Angelo has represented a young woman wearing a helmet. The most that can be said is that, when drawing it, he was unconsciously influenced by the recollection of Vittoria, idealised and rejuvenated; for the face possesses Vittoria's regular features and her severe expression. The eyes are absorbed in thought and the look is hard. The neck is bare, the breasts uncovered. The expression is cold and concentrated in its violence.

- ↑ So is she represented on an anonymous medal reproduced in the "Carteggio di Vittoria Colonna," published by Ermanno Ferrero and Giuseppe Müller, and thus, doubtless, Michael Angelo saw her. Her hair is hidden by a large striped head-dress, and she wears a dress severely closed, with an indentation at the neck. Another anonymous medal represents her young and idealised. (Reproduced in Müntz's "Histoire de l'Art pendant la Renaissance," iii, p. 248, and in "L'Œuvre et la Vie de Michel-Ange," published by the Gazette des Beaux- Arts.) Her hair is gathered up and tied above her forehead by means of a ribbon; a curl hangs down on her cheek and finely plaited tresses fall on her neck. Her forehead is high and straight; her eyes look with a somewhat indolent attention; her long, regular nose has broad nostrils; her cheeks are full, her ears large and well formed; her straight, strong chin is raised; her neck, entwined with a light veil, is, like her breast, bare. She has a sulky and indifferent air.These two medals, produced at different ages, have the following characteristics in common: a contraction of the nostrils and the somewhat sulky upper lip, and a small, tightly-closed, disdainful mouth. The face, as a whole, is expressive of a calm, without illusions and without joy.Frey contends, in a somewhat hazardous manner, that he has discovered Vittoria's portrait in a strange drawing by Michael Angelo on the back of a sonnet—a beautiful and sad drawing which Michael Angelo would have refused, in that case, to show to any one. The figure is that of an aged woman, nude to the waist, and with empty, pendent breasts. The head has not grown old—it is upright, pensive, and proud. A necklace surrounds the long and delicate neck; the hair, gathered up, is enclosed in a cap, which is attached under the chin, hides the ears and forms a sort of helmet. Facing her the head of an old man, resembling Michael Angelo, looks at her—for the last time. Vittoria Colonna had just died when this drawing was made. The sonnet which accompanies it is the fine poem on the death of Vittoria commencing with the words: "Quand' el ministro de sospir mie tanti …" Frey has reproduced the drawing in his edition of the " Poems of Michael Angelo," p. 385.

- ↑ Her spiritual counsellor at that time was Matteo Giberti, Bishop of Verona, who was one of the first to attempt the renovation of the Catholic Church. Giberti’s secretary was the poet Francesco Berni.

- ↑ Juan de Valdès, the son of a private secretary of Charles V., and who established himself in Naples in 1534, was the head there of the reform party. Nobles and great ladies grouped themselves around him. He published numerous works, the chief of which were the "Cento et dieci divine considerazioni" (Basle 1550) and an "Aviso sobre los interpretes de la Sagrada Escritura." He believed in justification through faith alone, and subordinated instruction by the Bible to illumination by the Holy Spirit. He died in 1541. It is said that he had more than three thousand followers in Naples.

- ↑ Bernardino Ochino, a great preacher and the Vicar-General of the Capucines in 1539, became the friend of Valdès, who came under his influence. In spite of denunciations, he continued his audacious sermons at Naples, Rome, and Venice, upheld by the people against the interdiction of the Church, until 1542, when, on the point of being punished as a Lutheran, he fled from Florence to Ferrara, and then to Geneva, where he became a Protestant. He was an intimate friend of Vittoria Colonna, and when about to leave Italy announced his resolution to her in a confidential letter.

- ↑ Pietro Carnesecchi, of Florence, prothonotary of Clement VII., the friend and disciple of Valdès, was summoned before the Inquisition in 1546 and was burnt in Rome in 1567. He remained in relations with Vittoria Colonna until her death.

- ↑ Gaspare Contarini, the member of a great Venetian family, was first Venetian Ambassador at the Court of Charles V., in the Netherlands, in Germany, and in Spain, and then, from 1528 to 1530, at the Court of Clement VII. He was appointed a Cardinal by Paul III. in 1535, and was legate in 1541 at the Diet of Ratisbonne. He did not succeed in coming to an understanding with the Protestants and he came under the suspicion of Catholics. He returned, discouraged, and died at Bologna in August 1542. He was the author of numerous works, such as "De immortalitate animæ," "Compendium primæ philosophiæ," and a treatise on "Justification," in which he came very near Protestant ideas concerning the question of grace.

- ↑ Quoted by Henry Thode.

- ↑ Giovanni Pietro Caraffa, Bishop of Chieti, founded in 1524 the Order of Theatines, and in 1528 began in Venice the work of counter-reform, which he was to continue with implacable rigour, first as a cardinal and then, in 1555, as Pope, under the title of Paul IV. The Order of the Jesuits was authorised in 1540; in July 1542 the Inquisition, with full powers against heretics, was established in Spain; and in 1545 the Council of Trent opened. This marked the end of the free Catholicism which had been dreamed of by the Contarinis, the Gibertis, and the Poles.

- ↑ Deposition of Carnesecchi before the Inquisition in 1566.

- ↑ Reginald Pole, of the House of York, had had to flee from England, where he had entered into conflict with Henry VIII. He went to Florence in 1532, became the enthusiastic friend of Contarini, was made a Cardinal by Paul III., and legate of the patrimony of St. Peter. Possessed of great personal charm and a conciliatory spirit, he undertook the work of counter-reform and lead back to obedience many of the free minds of the Contarini group, who were about to join the ranks of the Protestants. Vittoria Colonna placed herself entirely under his direction at Viterbo from 1541 to 1544. In 1554 Pole returned to England as Papal legate and became Archbishop of Canterbury. He died in 1558.

- ↑ Letter from Vittoria Colonna to Cardinal Morone (December 22, 1543). For details regarding Vittoria Colonna see the work of Alfred de Reumont and the second volume of Thode’s "Michael Angelo."

- ↑ Francisco de Hollanda’s "Quatre entretiens sur la peinture," held in Rome in 1538-1539, written down in 1548, and published by Joachim de Vasconcellos. French translation in "Les Arts en Portugal," by Comte A. Raczynski, 1846. Paris, Renouard.

- ↑ First part of the "Dialogue on Painting in the City of Rome."

- ↑ The same. Third part. On the day of this conversation. Octave Farnese, nephew of Paul III., married Margaret, the widow of Alessandro de' Medici. On this occasion a triumphal procession, with twelve cars after the fashion of ancient times, filed by on the Piazza Navone, where a large crowd had collected. Michael Angelo took refuge with his friends, amidst the quietness of San Silvestro, above the town.

- ↑ Condivi. These are not, truth to tell, the letters of Vittoria which have been preserved, and which are doubtless noble but a little cold. We must remember that of the whole of this correspondence we possess but five letters written from Orvieto and Viterbo, and only three from Rome, between 1539 and 1541.

- ↑ This drawing, as M. A. Grenier has shown, inspired the various "Pietà" which Michael Angelo carved later: that of Florence (1550-1555), the Rondanini "Pietà" (1563), and the more recently discovered one of Palestrina (between 1555 and 1560). Connected also with this conception are some drawings in the library at Oxford and the "Entombment" of the National Gallery.See A. Grenier's "Une Pietà inconnue de Michel-Ange à Palestrina," Gazette des Beaux-Arts, March 1907. Reproductions of the various "Pietà" will be found in this article.

- ↑ It was then that Michael Angelo thought of publishing a collection of his poems. His friends Luigi del Riccio and Donato Giannotti gave him the idea. Up to then he had not attached much importance to what he wrote. Giannotti occupied himself over this publication in 1545. Michael Angelo made a selection of his poems and his friends recopied them. But the death of Riccio in 1546 and that of Vittoria in 1547 diverted him from the idea, which now appeared to him to be a final piece of vanity. His poems were not published during his lifetime, with the exception of a small number, which appeared in the works of Varchi, Giannotti, Vasari, and others. But they passed from hand to hand. The greatest composers—Archadelt, Tromboncino, Consilium, and Costanzo Festa—set them to music. Varchi read and commented upon one of the sonnets in 1546 before the Academy of Florence. He found in it “antique purity and the fulness of the thoughts of Dante.”Michael Angelo was nourished on Dante. “No one understood him better,” said Giannotti, “or possessed his work more perfectly.” No one has addressed to him a more magnificent homage than the fine sonnet beginning with the words: “Dal ciel discese. …” (“Poems,” cix, 37). He was equally well acquainted with Petrarca, Cavalcanti, Cino da Pistoja, and the classics of Italian poetry. His style was modelled upon them. But the sentiment which vivified everything was his ardent platonic idealism.

- ↑ “Rime con giunta di xvi Sonetti spirituali,” 1539.“Rime con giunta di xxiv Sonetti spirituali e Trionfo della Croce,” 1544. Venice.

- ↑ “I possess a little parchment book which she gave me some ten years ago,” wrote Michael Angelo to Fattucci on March 7 1551. “It contains one hundred and three sonnets, without counting the forty on paper, which she sent me from Viterbo, and which I have had bound in the same little book. … I have also many letters which she wrote me from Orvieto and Viterbo. That is what I possess of her.”

- ↑ See Appendix, xvii ("Poems,"lxxxviii).

- ↑ Vasari. He quarrelled for a time with one of his dearest friends, Luigi del Riccio, because, against his wishes, he made him presents. "I am more oppressed by your extreme kindness," wrote Michael Angelo, "than if you robbed me. There must be equality between friends. If one gives more and the other less, then they come to blows; and if one is conquered, the other pardons not."

- ↑ Condivi.

- ↑ See Appendix, xviii ("Poems," ci).Michael Angelo added the following commentary:

"It (the hammer—that is Vittoria) was alone in this world to exalt virtue by its great virtues; there was no one here who worked the bellows of the forge. Now, in heaven, it will have many assistants; for there is no one there to whom virtue is not dear. Consequently, I hope that the completion of my being will come from on high. Now, in heaven, there will be some one to work the bellows; here below there was no assistant at the forge, where virtues are forged."

- ↑ See Appendix, xix (“Poems,” c).

On the back of the manuscript of this sonnet is the pen-and-ink drawing of a woman with wasted breasts which is alleged to be a portrait of Vittoria.

- ↑ Michael Angelo’s friendship for Vittoria Colonna did not exclude other passions. That friendship was not sufficient to satisfy his soul. Great care has been taken not to say so, through a ridiculous desire to “idealise” the artist. As though a Michael Angelo had need of being “idealised”! During the period of his friendship with Vittoria, between 1535 and 1546, Michael Angelo loved a “beautiful and cruel” woman—“donna aspra e bella” (cix, 89), “lucente e fera stella, iniqua e fella, dolce pieta con dispietato core” (cix, 9), “cruda e fera stella” (cix, 14), “bellezza e gratia equalmente infinita” (cix, 3); “my lady enemy,” as he also calls her, “la donna mia nemica” (cix, 54). He loved her passionately, humiliated himself in her presence, and would almost have sacrificed his eternal salvation for her sake: “Godo gl’inganni d’una donna bella …” (cix, 90); “porgo umilmente al’ aspro giogo il collo …” (cix, 54); “dolce mi saria l’inferno teco …” (cix, 55). He was tortured by this love. She amused herself with him:

She excited his jealousy, and coquetted with others. He ended by hating her. He implored Fate to make her ugly and enamoured of him, in order that he could no longer love her and make her suffer in her turn:“Cupid, why do you permit beauty to refuse your supreme courtesy to one who desires and appreciates you, whilst she accords it to stupid beings? Oh! grant that another time she has a loving heart, but so ugly a body that I love her not, and that she loves me!”See Appendix, xx (“Poems,” cix, 63).

“Questa mie donna è si pronta e ardita.

C’allor che la m’ancide, ogni mie bene

Cogli ochi mi promecte e parte tiene

Il crudel ferro dentro a la ferita …”

(cix, 15). - ↑ Vasari.

- ↑ Condivi.

- ↑ The idea of this immense fresco, which covers the wall at the entrance to the Sistine Chapel, above the papal altar, dated back to 1533, during the papacy of Clement VII.

- ↑ Vasari.

- ↑ Vasari.

- ↑ In July 1573. Veronese did not fail to rely on the example set him by “The Last Judgment.”“‘I admit that it is bad; but I repeat what I have said, that it is my duty to follow the examples which my masters have set me.’“What then have your masters done? Similar things, perhaps?” “‘Michael Angelo at Rome, in the Pope’s Chapel, has represented Our Lord, His Mother, St. John, St. Peter, and the Heavenly Court, and all these personages, even the Virgin Mary, are nude and in attitudes which have not been inspired by the severest religious feeling…’”—(A. Baschet’s “Paul Véronèse devant le Saint Office,” 1880.)

- ↑ It was done out of revenge. He had endeavoured, in his customary manner, to extort some works of art from him. Moreover, he had had the effrontery to outline a programme for “The Last Judgment.” Michael Angelo had politely declined this offer of collaboration and had turned a deaf ear to the demand for presents. Aretino wished to show Michael Angelo what lack of respect towards him might cost.

- ↑ One of Aretino’s comedies, “L'Hipocrito,” was the prototype of “Tartuffe” (P. Gauthiez’s “L'Arétin, 1895).

- ↑ He made an insulting allusion to “Gherardi and Tomai” (Gherardo Perini and Tommaso dei Cavalieri).

- ↑ This attempt at blackmail was impudently displayed. At the end of his threatening letter, after reminding Michael Angelo of what he expected from him—namely, presents—Aretino added the following postscript: “Now that I have somewhat expended my anger, and made you see that if you are “divino” I am not ‘acqua,’ tear up this letter, like me, and come to a decision …”

- ↑ By a Florentine in 1549 (Gaye, “Carteggio," ii, 500).

- ↑ In 1596 Clement VIII. also even thought of effacing "The Last Judgment.”

- ↑ In 1559. Daniello da Volterra was afterwards called "the breeches-maker" ("Il braghettone"). Daniello was a friend of Michael Angelo. Another of his friends, the sculptor Ammanati, condemned these nudes as a scandal. Michael Angelo was not even supported on this occasion by his disciples.

- ↑ The inauguration of "The Last Judgment" took place on December 25, 1541. People came from all over Italy, France, Germany, and Flanders to be present. For a description of the work, see my book on Michael Angelo in the series "Les Maîtres de l’Art," pp. 90-93.

- ↑ These frescoes ("The Conversion of St. Paul" and the "Martyrdom of St. Peter"), at which Michael Angelo worked from 1542, were interrupted, in 1544 and 1546, by two illnesses, and were painfully terminated in 1549-1550. They were "his last paintings," says Vasari, "and they cost him great labour, as painting, especially fresco, is not the work of an old man."

- ↑ These must have been his "Moses" and the two "Slaves"; but Michael Angelo decided that the latter were no longer suitable for a tomb thus reduced in size, so he carved two other figures "Active" and "Contemplative Life" (Rachael and Leah).

- ↑ Letter to an unknown “Monsignore” (October 1542). ("Letters," Milanesi’s edition, cdxxxv).