PART I

THE STRUGGLE

I

STRENGTH

“Davide cholla fromba

e io choll’archo”

He was born on March 6, 1475, at Caprese, in the Casentino—a rugged country of rocks and beech-trees and “pure air”[2] which dominates the backbone of the bony Apennines. Not far away, on Mount Alvernia, St. Francis of Assisi beheld his vision of the crucified Christ.

The father[3]—a violent, restless, “God-fearing” man—was podestat, or resident magistrate, of Caprese and Chiusi. The mother[4] died when Michael Angelo was six years of age.[5] They had five sons—Leonardo, Michelagniolo, Buonarroto, Giovan Simone and Sigismondo.[6]

He was put to nurse with the wife of a marble-worker of Settignano. Later, he jokingly attributed his vocation as a sculptor to his foster-mother's milk. Sent to school, he spent nearly the whole of his time drawing. "For this reason he was regarded with displeasure and often cruelly struck by his father and his father's brother, who had a hatred for the artistic profession and considered it a scandal to have an artist in the family."[7] Thus, whilst still a child, he came to know the brutality of life and the solitude of the mind.

His obstinacy prevailed over that of his father. At the age of thirteen he became an apprentice in the bottega of Domenico Ghirlandajo—the greatest and healthiest of Florentine painters. His early works were so successful that the master, it is said, was jealous of his pupil.[8] At the end of a year they separated.

He took a dislike to painting, and, aspiring to a more heroic art, entered the school of sculpture which Lorenzo de' Medici had established in the gardens of St. Mark.[9] The prince interested himself in him, lodged him in his palace and admitted him to his sons' table; and thus the child found himself at the very heart of the Italian Renaissance, in the midst of ancient collections, in the poetic and erudite atmosphere of those great Platonists Marsile Ficino, Benivieni, and Angelo Politiano. He became enraptured with their understanding. In order to live in the ancient world he cultivated an ancient soul and became a Greek sculptor. Guided by Politiano, "who loved him greatly," he carved a basso-relievo in

THE BATTLE OF THE CENTAURS

Unfinished bas-relief in the Galleria Buonarroti, Florence

This arrogant low-relief, in which impassable strength and beauty reign supreme, reflects the athletic soul of the young Hercules and his fierce games with his rough companions. Michael Angelo, accompanied by Lorenzo di Credi, Bugiardini, Granacci and Torrigiano dei Torrigiani, also went to the church of the Carmelites to copy Masaccio's frescoes. He was not sparing with the railleries which he addressed to his less skilful comrades. One day he attacked the vain Torrigiani, whereupon Torrigiani gave him a crushing blow on the face with his fist. Later he boasted of the fact to Benvenuto Cellini, in the following words: "I gave him so violent a blow upon the nose with my fist that I felt the bone and cartilage yield under my hand as if they had been made of paste, and the mark I then gave him he will carry to his grave."[11]

But paganism had not stifled Michael Angelo's Christian faith. The two hostile worlds disputed over his soul.

In 1490, Savonarola began his impassioned sermons on the Apocalypse. He was thirty-seven years of age. Michael Angelo was fifteen. The young artist saw the small, frail preacher, who was consumed by the Spirit of God, and the terrible voice which hurled thunderbolts on the Pope from the pulpit in the Duomo and suspended the bloody sword of God over Italy froze him with terror. Florence trembled. People rushed about the streets weeping and shouting like demented beings. The wealthiest citizens—the Ruccellais, the Salviatis, the Albizzis, and the Strozzis—demanded to enter into Orders. Learned men and philosophers, including Pic de la Mirandole and Politiano, themselves abdicated.[12] Michael Angelo's elder brother Leonardo became a Dominican.[13]

Michael Angelo did not escape this contagious terror. When he whom the prophet had announced approached—the new Cyrus, the sword of God, the little deformed monster, Charles VIII., King of France—he was panic-stricken. A dream threw his mind off its balance.

One of his friends, Cardiere, a poet and musician, saw, one night; the shade of Lorenzo de' Medici,[14] with his half-naked body wrapped in a black tattered robe. The dead man commanded him to tell his son Piero that shortly he would be driven from his house never again to return. Michael Angelo, to whom Cardiere confided the story of his vision, exhorted him to relate everything to the prince; but the poet, who was frightened of Piero, dare not. On one of the following mornings he again sought out Michael Angelo and, full of terror, told him that Lorenzo had once more appeared to him. He was wearing the same costume, and as Cardiere, who was lying down, looked at him in silence, the phantom had boxed his ears, as a punishment for not having obeyed him. Michael Angelo then warmly reproved his friend and forced him, there and then, to set off on foot to the villa of the Medici family, at Careggi, near Florence. When half way on his journey Cardiere met Piero, stopped him and related his story. Piero burst into laughter and had him belaboured by his attendants. The prince's chancellor, Bibbiena, said to him: "You are out of your mind. Whom do you think Lorenzo loves best, his son or you? If his son, would he not rather have appeared to him than to any other person, if it had been necessary to appear at all?" Cardiere, lashed and scoffed at, returned to Florence, informed Michael Angelo of the failure of his journey, and so convinced him on the subject of the misfortunes which were going to overtake Florence that, two days later, the sculptor fled.[15]

This was the first attack of those superstitious terrors which occurred more than once in the course of his life and which, however ashamed he might be of them, threw him into consternation.

He fled as far as Venice.

PIETA

St. Peter's, Rome

On the knees of the Virgin—immortally young—the dead Christ is lying, and seems asleep. The severity of Olympus hovers on the features of the pure goddess and of the God of Calvary. But an indescribable melancholy is mingled with it and envelops these beautiful bodies. Sadness had taken possession of Michael Angelo's soul.

It was not merely the sight of wretchedness and crime which had thrown a gloom over him. A tyrannical force had taken possession of him and was never to set him free. He was a prey to that genial passion which was to stifle him until the day of his death. Without having any illusions as regards the victory, he had sworn to conquer for the sake of his own glory and that of his kindred. The whole weight of his heavy family rested on his shoulders alone. He was beset with demands for money. Money was none too plentiful, but ever to refuse wounded his pride: he would have sold himself in order to send his family the sums they demanded. Already his health had begun to deteriorate. Poor food, cold, damp and overwork had begun to ruin him. He suffered in his head and had a swollen side.[20] His father reproached him for the manner in which he lived: he did not mention that he was responsible for it.

"All the hardships which I have endured, I have endured for you," wrote Michael Angelo to him later.[21] ". . . All my cares, all of them, I have suffered through my love for you."[22]

In the spring of 1501 he returned to Florence.

Forty years before, a gigantic block of marble had been entrusted by the Opera del Duomo to Agostino di Duccio to make the figure of a prophet. The work—hardly commenced—had been interrupted and no one dare continue it. Michael Angelo took it in hand[23] and transformed the ill-shapen block into a colossal statue of David.

It is related that the gonfaloniere Pier Soderini, on coming to see this statue, which he had ordered from Michael Angelo, addressed a few critical remarks to him, in order to show his taste: he pretended to discover that the nose was a little too large. Whereupon Michael Angelo mounted the scaffolding, took a chisel and a little marble dust, and, whilst lightly moving the chisel, allowed the dust to fall, little by little. But he took very good care not to touch the nose and left it as it was. Then, turning towards the gonfaloniere, he said:

DAVID

Academy of Fine Arts, Florence

“Now,” replied Soderini, “it pleases me much better. You have given it life.”

Michael Angelo then descended, laughing silently.[24]

We can imagine we can read the sculptor’s silent contempt in this work. It represents tumultuous strength at rest. It is, as it were, swollen with disdain and melancholy. It is smothered within the walls of a museum. It requires the open air, “the light on the square,” as Michael Angelo once put it.[25]

On January 25, 1504, a committee of artists, including Filippino Lippi, Botticelli, Perugino and Leonardo da Vinci, deliberated over the question of the site for the “David.” At the request of Michael Angelo they decided to place it in front of the Palazzo Vecchio.[26] The removal of the enormous block was entrusted to the architects of the Cathedral. On the evening of May 14 the marble colossus was brought out from the wooden construction where it was kept, a wall above a door being demolished in doing so. During the night the populace attempted to shatter it with stones and it had to be strongly guarded. Slowly the huge statue—suspended in an upright position, so that it could swing freely without striking the ground—advanced. It took four days to move it from the Duomo to the Old Palace. On the 18th, at noon, it reached its destination. They continued to keep a guard around it at night, but, one evening, in spite of all precautions, it was stoned.[27]

Such was that Florentine people who are sometimes held up to us as a model.[28]

In 1504 the Seigniory of Florence pitted Michael Angelo against Leonardo da Vinci.

The two men were not fond of each other. Their common solitude ought to have brought them together. But if they felt that they were far removed from the rest of men, they were still more distant the one from the other. The more isolated of the two was Leonardo. He was fifty-two years of age—twenty years Michael Angelo's senior. Since the age of thirty he had been absent from Florence, the bitterness of whose passions was intolerable to his somewhat timid and delicate nature, to his serene and sceptical intellect, open to everything and understanding everything. This great dilettante, this man absolutely free and absolutely alone, was so detached from native country, religion and the entire world that he was only at his ease when with tyrants, who, like himself, were free minded. Forced to leave Milan in 1499, owing to the fall of his protector, Lodovico il Moro, he had entered the service, in 1502, of Caesar Borgia; but the end of the political career of that prince obliged him, in the following year, to return to Florence. There his ironical smile was to be observed side by side with the melancholy, feverish nature of Michael Angelo, and it exasperated the sculptor. Michael Angelo, absorbed in his passions and his faith, hated the enemies of his passions and his faith, but he hated much more those who were without passion and belonged to no faith at all. The greater Leonardo was the more Michael Angelo felt an aversion for him; and he let no opportunity slip of showing it.

"Leonardo was a handsome man with engaging and distinguished manners. One day he was sauntering with a friend in the streets of Florence. He was dressed in a pink tunic, reaching to his knees, and his well-curled, artistically arranged beard floated on his breast. Near Santa Trinità a group of citizens were discussing a passage in Dante. Calling Leonardo to them, they begged him to explain the meaning. At that moment Michael Angelo was passing. Leonardo said 'Michael Angelo here will explain the verses of which you speak.' Michael Angelo, thinking that he wished to laugh at him, replied bitterly: 'Explain them yourself, you who made the model of a bronze horse,[29] and who, incapable of casting it, left it unfinished—to your shame be it said!' Thereupon he turned his back on the group and continued on his way. Leonardo remained and reddened. And Michael Angelo, not yet satisfied and burning with a desire to hurt him, cried: 'And those thieves the Milanese who thought you capable of such a work!'"[30] Such were the two men whom the gonfaloniere Soderini set in opposition over a common work: the decoration of the Council Chamber of the Palace of the Seigniory. A singular combat this between the two greatest forces of the Renaissance! In May 1504 Leonardo began his cartoon of the "Battle of Anghiari."[31] In August 1504 Michael Angelo received a commission for the cartoon of the "Battle of Cascina."[32] Florence was divided into two camps. Time has equalised everything—both works have disappeared.[33]

In March 1505 Michael Angelo was summoned to Rome by Julius II. Then began the heroic period of his life.

THE HOLY FAMILY

In the Uffizi, Florence

In December 1505 he returned to Rome, where the blocks of marble which he had chosen had begun to arrive by sea. They were transported on to the square of St. Peter, behind Santa Caterina, where Michael Angelo lived. "The mass of stone was so great that it excited the astonishment of the people and the joy of the Pope." Michael Angelo set to work. The Pope, in his impatience, came to see him ceaselessly " and conversed with him as familiarly as though he had been his own brother." In order to visit him more conveniently he had a drawbridge, which assured him a secret passage, thrown from a corridor of the Vatican to Michael Angelo's house.

But the Pope's favour lasted only a short time. The character of Julius II. was no less inconstant than that of Michael Angelo. He became interested in the most dissimilar projects one after the other. Another plan — that of the rebuilding of St. Peter's—appeared to him to be more fitted to perpetuate his glory. He was urged to this by Michael Angelo's enemies, who were numerous and powerful. They were headed by a man whose genius was equal to that of Michael Angelo and who possessed a stronger will—Bramante d'Urbino, the Pope's architect and the friend of Raphael. There could not possibly be sympathy between the sovereign intellect of the two great Umbrians and the fierce genius of the Florentine. But if it is true that they decided to oppose him[35] it was doubtless because he had provoked them. Michael Angelo imprudently criticised Bramante, and accused him, whether rightly or wrongly, of malversation in his work.[36] Bramante immediately decided to ruin him.

He robbed him of the Pope's favour. Playing upon Julius' superstitious nature he reminded him of the popular belief that it was unlucky to build one's tomb during one's lifetime. And he succeeded not only in detaching him from his rival's projects but in substituting his own for them. In January 1506 Julius II. decided to rebuild St. Peter's. The mausoleum was abandoned, and Michael Angelo found himself not only humiliated but indebted for the expenses which he had incurred for the work.[37] He complained bitterly. The Pope closed his door to him, and, on the sculptor returning to the charge, Julius had him driven from the Vatican by one of his grooms.

A bishop of Lucca, who witnessed the scene, said to the man:

"Are you aware as to who this is?"

"Pardon me, sir," said the groom to Michael Angelo," but I have an order not to let you enter, and it is my duty to obey my orders."

Returning home, Michael Angelo wrote to the Pope as follows: "Holy Father! I was driven from the Palace this morning by order of your Holiness. I beg to inform you that if you need me you will have to seek me everywhere else but in Rome."

Sending off this letter, he called in a dealer and a marble-cutter who lodged with him and said to them:

"Find a Jew, sell everything in my house, and come to Florence." He then mounted his horse and set off.[38] When the Pope received the letter he despatched five couriers after him, but they did not overtake the fugitive until eleven o'clock at night, by which time he had reached Poggibonsi, in Tuscany. There they handed him the following order: "Immediately after the receipt of this, return to Rome, on pain of our disgrace." Michael Angelo replied that he would return when the Pope kept his engagements; otherwise, Julius II. might give up all hope of ever seeing him again.[39]

He addressed a sonnet to the Pope, as follows:[40]

"Lord, if ever a proverb was true, it is that which says that he who can, never will. You have believed in tales and idle talk; you have recompensed the enemy of truth. As regards myself, I am and have ever been your good old servant. I am as attached to you as the rays are to the sun. And yet the time which I lose afflicts you not! The more I fatigue myself the less you love me. I had hoped to grow greater through your grandeur, and that your just balance and your powerful sword would have been my only judges, and not a lying echo. But heaven makes a mockery of all virtue, in placing it in this world, if it counts on fruit from a dead tree."[41]

It is probable that the affront which he received from Julius II. was not the sole reason for Michael Angelo's flight. In a letter to Giuliano da San Gallo he leads one to suppose that Bramante intended to have him assassinated.[42]

Michael Angelo having left, Bramante remained sole master. On the day after his rival's flight he laid the foundation-stone of St. Peter's.[43] His implacable hatred continued to be directed against Michael Angelo's work, and he took steps to ruin it for ever by causing the populace to pillage the workyard on St. Peter's Square where the blocks of marble for the tomb of Julius II. had been collected together.[44]

However, the Pope, enraged by the revolt of his sculptor, despatched brief after brief to the Seigniory of Florence, where Michael Angelo had taken refuge. The Seigniory sent for the artist and said to him: "You have done by the Pope what the King of France would not have presumed to do. We do not wish, because of you, to enter into a war with his Holiness, so you must return to Rome. We will give you letters of such weight that any injustice which may be done to you will also be done to the Seigniory."[45]

But Michael Angelo became obstinate. He laid down conditions. He demanded that Julius should allow him to make his mausoleum, and he stipulated that the work should be carried out not in Rome but in Florence. When Julius made war against Perugia and Bologna[46] and his summonses became more menacing, Michael Angelo thought of escaping to Turkey, the Sultan, through the Franciscans, having invited him to Constantinople to build a bridge at Pera.[47]

Finally, however, he had to give way, and, during the last days of November 1506, he reluctantly proceeded to Bologna, where Julius II. had entered with his conquering army.

"One morning Michael Angelo went to hear Mass at San Petronio. The Pope's groom recognised him and led him before Julius, who was at table at the Palace of the Sixteen. The Pope, irritated, said to him: 'It was your duty to come to seek us (at Rome); but you waited for us to find you (at Bologna)!' Michael Angelo threw himself on his knees and in a loud voice begged for pardon, saying that he had not acted through malice but irritation, because he could not bear being driven away, as had been done. The Pope remained seated, with bent head and face flushed with anger, whereupon a bishop, whom Soderini had sent to defend Michael Angelo, attempted to intervene by saying: 'May it please your Holiness to pay no heed to his stupidities: he sinned through ignorance. Apart from their art, painters are all the same.' At this the Pope became furious and cried: 'What you say is an insult, which comes not from us! You are the ignorant one! . . . Away with you and the devil take you!' And as he did not do as he was told, the Pope's servants threw themselves upon him, with blows, and expelled him from the room. Then, the Pope, having spent his anger on the bishop, made Michael Angelo approach and pardoned him."[48]

Unfortunately, in order to make peace with Julius II., it was necessary to humour his caprices, and the powerful will had again changed. There was no longer any question of a mausoleum but of a colossal bronze statue which he proposed to raise at Bologna. In vain did Michael Angelo protest "that he knew nothing about the casting of bronze." He had to set to work to learn, with the result that his life became a torment. He lived in a wretched room, with a single bed, in which he slept with his two Florentine assistants, Lapo and Lodovico, and with his metal-founder, Bernardino. Fifteen months passed full of all sorts of troubles. He quarrelled with Lapo and Lodovico, who robbed him.

"This scamp Lapo," he wrote to his father, "gave every one to understand that he and Lodovico did all the work, or at least that they worked in collaboration with me. He could not understand that he was not the master until I turned him out; then, for the first time, did he see that he was in my employment. I drove him forth as I would a brute."[49]

Lapo and Lodovico complained noisily, and, in addition to spreading calumnies against Michael Angelo in Florence, succeeded in extorting money from his father under the pretext that he had robbed them.

The incapacity of the founder next became apparent.

"I would have believed that Maestro Bernardino was capable of casting even without fire, so great was my faith in him."

In June 1507 the casting of the statue failed; the figure was successful only as far as the waist. Everything had to be recommenced. Michael Angelo was occupied with the work until February 1508 and nearly ruined his health over it.

"I have hardly time to eat," he wrote to his brother. "I live in a state of the greatest inconvenience and difficulty. I think of nothing else than working night and day. I have endured such sufferings, and I continue to endure them, that I believe that if I had the statue to make once more my life would not suffice for the task. It has been a gigantic undertaking.”[50]

Considering the fatigue entailed, the fate which was in store for this work of art was pitiful. Erected in February 1508 in front of the façade of San Petronio, the statue of Julius II. remained there but four years. In December 1511 it was destroyed by the party of the Bentivoglio family, the enemies of Julius II., and Alfonzo d’Este bought the fragments to make a cannon.

Michael Angelo returned to Rome. Julius now imposed upon him another task, no less unexpected and still more perilous. He ordered the painter, who knew nothing about the technique of fresco painting, to paint the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel. One would have said that he took pleasure in ordering impossible things and Michael Angelo in carrying them out.

THE PROPHET JEREMIAH

In the Sistine Chapel

Bramante raised a scaffolding for Michael Angelo in the Sistine Chapel, and some painters who had had experience in fresco painting were brought from Florence to assist him. But Michael Angelo was one of those men who would receive no sort of assistance whatsoever. He began by declaring that Bramante’s scaffolding was useless and by raising another. As to the Florentine painters, he took a dislike to them, and, without explanation, put them to the door. “One morning he destroyed everything they had painted, shut himself up in the chapel and would not open the door to them. He would not let himself be seen even in his own house. When the joke seemed to them to have lasted long enough they returned to Florence, profoundly humiliated.”[53]

Michael Angelo remained alone with a few workmen,[54] and, far from the greater difficulty checking his boldness, he enlarged his plan and decided to paint not only the ceiling, as had at first been proposed, but the walls.

This gigantic undertaking was begun on May 10, 1508. Dark years—the darkest and the most sublime of his whole life! Here we see the legendary Michael Angelo, the hero of the Sistine, he whose majestic image is and ought to remain engraved on the memory of humanity.

He suffered terribly. His letters of those days witness to a passionate discouragement, which could not find appeasement in his divine thoughts.

"I am in a state of great mental depression: it is a year now since I received a fixed income from the Pope. I ask him for nothing, because my work does not advance sufficiently to make remuneration appear to me to be merited. This arises from the difficulty of the work and also from the fact that it does not belong to my profession. Thus I lose my time without result. God help me!"[55]

Hardly had he finished painting "The Deluge" than the work became so mouldy that the figures could no longer be distinguished. He refused to continue. But the Pope would hear of no excuse. The artist had to set to work again.

His relatives still further added to his fatigue and anxiety by their odious importunities. All the members of his family lived at his charge, took advantage of him and worried him to death. His father never ceased his moaning and complaining over money affairs. When Michael Angelo himself was crushed under troubles he had to spend his time in raising his father’s courage.

"Do not distress yourself," he wrote to him, “these are not matters in which life is at stake . . . I shall never see you want as long as I myself have anything . . . Even if everything you possess in the world is taken from you, you will lack nothing so long as I exist . . . I would rather be poor and know you were alive than have all the gold in the world and know you were dead . . . If you cannot, like others, have the honours of this world, be content with having bread, and live with Christ, good and poor, as I do here. For I am wretched, and yet I torment myself neither over life nor honour—that is to say over the world. I live under very great difficulties and in a state of infinite distrust. For the past fifteen years I have not had a good hour. I have done everything to support you, and never have you either recognised or believed it. God pardon us all! I am ready, in the future and as long as I live, ever to act in the same manner, provided that I am able to do so!”[56]

His three brothers exploited him. They expected him to provide them with money and position; they helped themselves without scruple to the little capital which he had amassed at Florence; they quartered themselves upon him in Rome. Buonarroto and Giovan Simone bought the goodwill of a business, and Sigismondo land near Florence. And yet they showed no gratitude towards him; they acted as though all this was their due. Michael Angelo knew that they were taking advantage of him, but he was too proud to prevent them. The scamps did not limit themselves to this. They conducted themselves badly and, in Michael Angelo's absence, ill-treated the father. Furious threats then came from the artist. He governed his brothers, as though they were vicious boys, with the lash. Had need be, he would have killed them.

“Giovan Simone,[57] it is said that he who does good to the righteous makes him better, but that kindness shown to the wicked makes him worse. Many years have I endeavoured by fair words and fair actions to lead you to an honest life, in peace with your father and we others. Yet you are ever worse . . . I might speak to you at great length; but that would only be wasting words. To bring matters to a conclusion, know with certainty that you possess nothing in the world, for it is I who, through love of God and believing that you were one of my brothers, support you. But now I am certain that you are not my brother, for if you had been you would not have threatened my father. Rather are you a brute, and I shall treat you as a brute. Know that it is the duty of him who sees his father threatened or ill-treated to expose his life for him . . . But enough on this subject! . . . I repeat that you possess nothing in the world, and that if I hear but the slightest complaint against you I shall come to teach you for squandering your property and setting fire to the house and estates which you have not earned. You are not in the position you imagine. If I come to you I shall make you acquainted with facts which will bring bitter tears to your eyes and show you on what basis you establish your arrogance … If you will endeavour to act well, to honour and venerate your father, I will assist you as I do the others, and, shortly, will procure you a good shop. But if you do otherwise I shall come and arrange your business in such a manner that you will know who you are and exactly what you possess in the world . . . Nothing more! When words are lacking I make up for them by deeds.

"Michelagniolo at Rome.

"Two lines more. For the past twelve years I have lived a wretched life all over Italy. I have supported every disgrace, suffered every difficulty, tormented my body with all sorts of fatigue and exposed my life to a thousand dangers solely in order to aid my house. And now that I have begun to raise it up a little, you amuse yourself by destroying in an hour what has taken years to build! . . . By the body of Christ this shall not be! For I am capable of tearing in pieces ten thousand such men as you, if that is necessary. Be wise, therefore, and do not drive one whose passions are different to yours to extremes!"[58]

It was then Sigismondo’s turn.

"I am living here in distress and in a state of great bodily fatigue. I have no friend of any kind and do not want any . . . It is rarely that I have the means to eat to my liking. Cease to cause me anguish, for I can support no more."[59]

Finally, the third brother, Buonarroto, employed in the commercial house of the Strozzis, shamelessly harassed him, after all the advances of money he had received from Michael Angelo, and boasted that he had spent more for him than he had received.

"I should very much like to know,” wrote Michael Angelo to him, "where your money comes from. I should much like to know if you count the 228 ducats which you took from me at the Santa Maria Nuova bank, the many other hundreds of ducats which I have sent home, and the difficulties and cares which I have had in supporting you. I should much like to know if you take all that into account! If you had sufficient intelligence to recognise the truth, you would not say: 'I have spent so much of my own,' and you would not have beset me here, tormenting me with your affairs, without recollecting all my past conduct towards you. You would have said: 'Michael Angelo knows what he wrote to us; if he does not do it now it is because he has been prevented by something of which we are in ignorance. Let us be patient.' When a horse runs as fast as he can, it is unwise to give him the spur, to make him run more than he is able. But you have never known me. God pardon you! He it is who has granted me the strength to do all that I have done to assist you. But you will not recognise it until I am no more."[60]

Such was the atmosphere of ingratitude and envy in the midst of which Michael Angelo struggled—between an unworthy family which harassed him and relentless enemies who watched him and anticipated his failure. And yet, during this period, he was accomplishing the heroic work in the Sistine Chapel. But at the price of what desperate efforts! He nearly abandoned everything and fled once more. He was under the impression that he was going to die.[61] Perhaps he would have welcomed death.

The Pope became irritated at his slowness and obstinacy in hiding his work. Their proud characters dashed against each other like thunderclouds. "One day," says Condivi, "on Julius II. asking him when he would have finished the chapel, Michael Angelo made his usual reply, 'When I am able.' The Pope, furious,

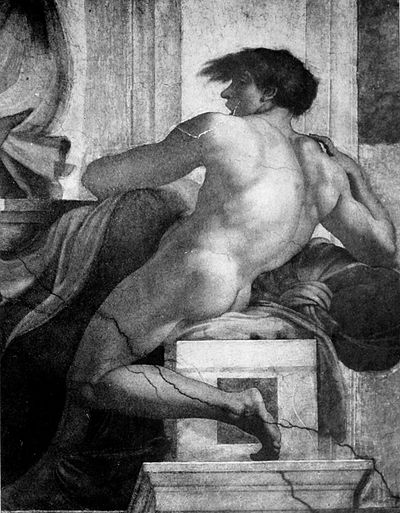

DECORATIVE FIGURE

In the Sistine Chapel

But they recommenced on the morrow. One day the Pope ended by saying to him angrily: “Do you want me to have you thrown from the top of your scaffolding?” Michael Angelo had then to give way; he took down the scaffolding, and on All Saints’ Day 1512 his work was uncovered.

That great and melancholy fête, which receives the funereal reflection of All Souls’ Day, was eminently fitted for the inauguration of Michael Angelo’s terrible work, full of the spirit of God who creates and destroys—the devouring God in whom the whole force of life rushes like a tempest.[62]

- ↑ Poems, i. (Written on a page of drawings in the Louvre, near to the sketches for his “David.”)

- ↑ Michael Angelo was fond of saying that he owed his genius to “the pure air of the district of Arezzo.”

- ↑ Lodovico di Leonardo Buonarroti Simone. The real name of the family was Simoni.

- ↑ Francesca di Neri di Miniato del Sera.

- ↑ A few years later, in 1485, the father remarried with Lucrezia Ubaldini, who died in 1497.

- ↑ Leonardo was born in 1473; Buonarroto in 1477; Giovan Simone in 1479; Sigismondo in 1481. Leonardo became a monk. Michael Angelo thus became the eldest, the head of the family.

- ↑ Condivi.

- ↑ Truth to tell, it is difficult to believe that so powerful an artist would have been jealous. At all events, I do not believe that this was the cause of Michael Angelo's precipitous departure. He preserved, until his old age, the respect of his first master.

- ↑ The school was directed by Bertoldo, a pupil of Donatello.

- ↑ The "Battle of Hercules with the Centaurs" is at the Casa Buonarroti in Florence. Belonging to the same period are two other works: The "Mask of a Laughing Faun," which brought Michael Angelo Lorenzo de' Medici's friendship, and the "Madonna of the Staircase," another low-relief of the Casa Buonarroti.

- ↑ This incident occurred about 1491.

- ↑ They died shortly afterwards, in 1494. Politiano requested to be buried as a Dominican at the Church of St. Mark—Savonarola's church. When about to die Pic de la Mirandole put on the dress of a Dominican.

- ↑ In 1491.

- ↑ Lorenzo de' Medici had died on April 8, 1492, and was succeeded by his son, Piero. Michael Angelo then left the palace and returned to his father's, where he remained for some time without employment. Taking him into his service again, Piero charged him with the purchase of cameos and intaglios. His next piece of work was a colossal Hercules in marble, which, after being at the Strozzi Palace, was purchased in 1529 by Francis I. and placed at Fontainebleau, where, in the seventeenth century, it disappeared. The "Crucifix de Bois" of the Convent of San Spirito, in the making of which Michael Angelo studied anatomy on dead bodies to such an extent that he fell ill (1494), also belongs to this period.

- ↑ Condivi. Michael Angelo's flight took place in October 1494. A month later Piero de' Medici fled in his turn, before a rising of the people, and a popular government was established in Florence, with the support of Savonarola, who prophesied that the city would carry the Republic throughout the world. This Republic recognised, however, a king—Jesus Christ.

- ↑ He was the guest of the nobleman, Giovanni Francesco Aldovrandi, who, on the occasion of certain troubles which ho had with the police of Bologna, came to his assistance. He was then working on the statue of San Petronio and a statuette of an angel for the tabernacle (Arca) of San Domenico. But these works are in no way religious in their character. Arrogant strength still prevailed in his work.

- ↑ Michael Angelo arrived in Rome in June 1496. The "Bacchus Drunk," the "Dying Adonis" (Bargello Museum), and the "Cupid" (South Kensington) are of 1497. He also seems to have drawn at this time the cartoon for a "Stigmatisation of St. Francis" for the Church of San Pietro in Montorio.

- ↑ May 23. 1498.

- ↑ It has always been stated up to the present that "La Pietà" was executed for the French Cardinal, Jean de Groslaye de Villiers, Abbot of St. Denis and Ambassador of Charles VIII., and that he ordered it of Michael Angelo for the Chapel of the Kings of France at St. Peter's. (Contract of August 27, 1498.) But M. Charles Samaran, in a work on "La Maison d'Armagnac au XVe siècle," has proved that the French cardinal who commissioned the work was Jean de Bilhères, Abbot of Pessan, Bishop of Lombez, and Abbot of St. Denis. Michael Angelo worked on it until 1501.

A conversation between Michael Angelo and Condivi explains, by a thought full of chivalrous mysticism, the youth of the Virgin, so different from the rude and blighted Mater Dolorosa, convulsed by sorrow, of Donatello, Signorelli, Mantegna, and Botticelli.

- ↑ Letter from his father, December 19, 1500.

- ↑ Letter to his father, spring 1509.

- ↑ Letter to his father, 1521.

- ↑ In August 1501. A few months earlier he had signed with Cardinal Francesco Piccolomini a contract (which he never carried out) for the decoration of the Piccolomini altar at the Cathedral of Sienna. The breaking of this engagement caused him remorse during the whole of his life.

- ↑ Vasari.

- ↑ “Don’t give yourself so much trouble,” said Michael Angelo to a sculptor who was striving to arrange the light in his studio, in order that his work might appear to advantage, “the great essential is the light on the square.”

- ↑ The account of the deliberations has been preserved. (Milanesi: “Contratti Artistici,” pp. 620 et seq.) The “David” remained on the spot which had been fixed for it in front of the Palace of the Seigniory until 1873. As the rain had damaged the statue in an alarming manner, it was then removed to a special rotunda (the “Tribuna del David”) at the Academy of Fine Arts in Florence. The “Circolo Artistico” of that city is now proposing (1908) to have a white marble copy made and erected on its old site opposite the Palazzo Vecchio.

- ↑ Contemporary narrative and Pietro di Maico Parcnti's "Florentine Stories."

- ↑ Let me add that the chaste nudity of the "David" shocked the Florentines. Aretino, reproaching Michael Angelo with the indecency of his "Last Judgment," wrote to him in 1515: "Imitate the modesty of the Florentines, who hide under leaves of gold the shameful parts of their beautiful Colossus."

- ↑ An allusion to the equestrian statue of Francesco Sforza, which Leonardo left unfinished, and the plaster model of which the Gascon archers of Louis XII. used as a mark.

- ↑ Narrative of a contemporary.

- ↑ They imposed upon him the humiliation of representing a victory of the Florentines over his friends the Milancse.

- ↑ Or the "War of Pisa."

- ↑ Michael Angelo's cartoon, the only one completed in 1505, disappeared in 1512, on the occasion of the riots which arose in Florence through the return of the Medicis. The work is now known only by means of fragmentary copies, the most famous of these being Marc Antonio's engraving, "The

Climbers." As to Leonardo's fresco, the painter himself destroyed it. Wishing to perfect the technique of the fresco, he experimented with a plaster which had oil as its basis, and which failed to last; and thus the painting, which, in his discouragement, he abandoned in 1506, no longer existed in 1550.

To this period of Michael Angelo's life (1501-1505) also belong the two circular bas-reliefs of the "Madonna and the Child," which are at the Royal Academy in London and at the Bargello Gallery in Florence; the "Madonna of Bruges," purchased in 1506 by Flemish merchants; and the large picture in distemper of the "Holy Family" in the Uffizi, the finest and most carefully finished of Michael Angelo's works. Its Puritanical austerity and heroic accent is a striking contrast to the effeminate languor of the art of Leonardo. - ↑ Condivi.

- ↑ At any rate, Bramante. Raphael was too close a friend of Bramante and too much under an obligation to him to refuse to make common cause with him; but we have no proof that, personally, he acted against Michael Angelo. Nevertheless, the sculptor accuses him in formal terms: " All the difficulties which arose between the Pope Julius and myself were the result of the jealousy of Bramante and Raphael. They sought to ruin me; and truly Raphael had reason for doing so, for what he knows in art he learnt from me." (Letter of October 1542 to a person unknown. Letters, Milanesi's edition, pp. 4S9-494).

- ↑ Condivi, whose blind friendship for Michael Angelo renders him somewhat open to suspicion, says: "Bramante was impelled to harm Michael Angelo first of all through jealousy, but also owing to a fear of the judgment of Michael Angelo, who discovered his errors. Bramante, as every one knows, was given to pleasure and great dissipation. The salary which he received from the Pope, large though it was, was insufficient for him, so ho sought to make money by building his walls of bad materials and insufficiently solid. Every one can see this in his buildings at St. Peter's, the corridor of the Belvedere, the cloister of Santo Pietro ad Vincula, &c., which it has recently been necessary to support by means of cramp-irons and buttresses, because they were falling or would soon have fallen."

- ↑ When the Pope changed his mind and the ships arrived with the marble from Carrara, I had to pay the freight myself. At the same time the marble-cutters, for whom I had sent to Florence, arrived in Rome; and as I had furnished and fitted up for them the house which Julius had given me behind Santa Caterina, I found myself without money and in great embarrassment..." (Letter already quoted, October 1542.)

- ↑ April 17, 1506.

- ↑ The whole of this narrative is taken, textually, from a letter by Michael Angelo, dated October 1542.

- ↑ I place it at this date, which appears to me to be the most likely one, although Frey, without, in my opinion, sufficient reason, claims that it was written about 1511.

- ↑ Poems," iii. (See Appendix, i.)

The dead tree "is an allusion to the evergreen oak which figures on the arms of the De la Rovere family—that of Julius II. - ↑ That was not the only cause of my departure; there was another, of which I prefer not to speak. Suffice it to say, that I had reason for tliinking that, had I remained in Rome, that city would have been my tomb, rather than that of the Pope. And that was the cause of my sudden departure."

- ↑ April 18, 1506.

- ↑ Letter of October 1542.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ End of August 1506.

- ↑ Condivi. In 1504 Michael Angelo had already thought of going to Turkey, and in 1519 he was in relations with "the Lord of Andrinopolis," who invited him to come and execute some paintings for him.Leonardo da Vinci was also tempted to go to Turkey.

- ↑ Condivi.

- ↑ Letter to his father, February 8, 1507.

- ↑ Letters to his brother, September 29 and November 10, 1507.

- ↑ Such, at any rate, is the contention of Condivi. It is, however, to be noted that, before Michael Angelo’s flight to Bologna, the question of him painting the Sistine Chapel had been raised, and that then this project was little to the liking of Bramante, who sought to remove his rival from Rome. (Letter from Pietro Rosselli to Michael Angelo in May 1506.)

- ↑ Raphael painted the room known as the “Stanza della Signatura” (“The School of Athens” and the “Dispute of the Holy Sacrament”) between April and September 1508.

- ↑ Vasari.

- ↑ In the letters of 1510 to his father, Michael Angelo laments on the subject of one of these assistants, who was good for nothing “except to be waited upon . . . . . This occupation was doubtless lacking to me! I had not enough to do already! . . . . He makes me as wretched as a brute.”

- ↑ Letter to his father. (January 27, 1509.)

- ↑ Letters to his father, 1509–1512.

- ↑ Giovan Simone had just ill-treated his father. Michael Angelo wrote to the latter as follows:

“I have seen from your last letter how things are and how Giovan Simone is behaving. I have not had worse news for the past ten years . . . Had it been possible, on the day I received your letter, I should have mounted into the saddle and put everything in order. But since I cannot do that, I am writing to him; and if he does not change his disposition, or if he carry off but a toothpick from the house, or does anything to displease you, I beg you to inform me. I will then obtain leave of absence from the Pope and come to you." (Spring 1509.)

- ↑ Letter to Giovan Simone. Dated by Henry Thode, spring 1509; in Milanesi’s edition, July 1508. It is to be noted that Giovan Simone was then a man of thirty. Michael Angelo was only four years his senior.

- ↑ To Sigismondo, October 17, 1509.

- ↑ Letter to Buonarroto, July 30, 1513.

- ↑ Letters, August 1512.

- ↑ I have analysed the work in my book on Michael Angelo in the series entitled “Les Maîtres de l’Art,” and need not here return to the subject.