THE

PRIMEVAL ANTIQUITIES

OF

DENMARK.

BY

J. J. A. WORSAAE,

A FOREIGN MEMBER OF THE SOCIETY OF ANTIQUARIES OF LONDON, &C., AND A ROYAL COMMISSIONER FOR THE PRESERVATION OF THE NATIONAL MONCMENTS OF DENMARK.

TRANSLATED, AND APPLIED TO THE ILLUSTRATION OF SIMILAR REMAINS IN ENGLAND,

BY

WILLIAM J. THOMS,

A FELLOW OF THE SOCIETY OF ANTIQUARIES, CORRESPONDING MEMBER OF THE SOCIETY OF ANTIQUARIES OF SCOTLAND, AND SECRETARY OF THE CAMDEN SOCIETY.

ILLUSTRATED WITH NUMEROUS WOODCUTS.

LONDON,

JOHN HENRY PARKER:

AND BROAD-STREET, OXFORD.

M DCCC XLIX.

OXFORD:

PRINTED BY I. SHRIMPTON.

DEDICATED

TO THE

FELLOWS OF THE SOCIETY OF ANTIQUARIES OF LONDON,

AND

TO THE MEMBERS OF THE VARIOUS ARCHÆOLOGICAL SOCIETIES

OF

GREAT BRITAIN AND IRELAND,

BY

J. J. A. WORSAAE,

WILLIAM J. THOMS.

CONTENTS.

- Preface to the English Edition, written by the Authoriii

- Preface by the Editor of the English Editionix

- Introduction1

FIRST DIVISION.

- Of our Antiquities7

- I. Antiquities of the Stone-period9

- II. Antiquities of the Bronze-period23

- III. Antiquities of the Iron-period45

SECOND DIVISION.

- Of Stone Structures, Barrows, &c.76

- Graves of the Stone-period, or Cromlechs, (Steendysser)78

- Giants' Chambers (Jættestuer)86

- II. Tombs of the Bronze-period93

- III. Tombs of the Iron-period98

- IV. Tombs in other Countries, (particularly in Sweden and Norway)105

- V. Runic Stones115

THIRD DIVISION.

- I. Importance of the Monuments of Antiquity for History121

- § 1. The Stone-period127

- § 2. The Bronze-period136

- § 3. The Iron-period144

- II. Importance of the Monuments of Antiquity as regards Nationality149

APPENDIX.

- On the Examination of Barrows, and the Preservation of Antiquities151

Illustrations of Terminology, three plates, to face p. 1.

PREFACE

TO

THE ENGLISH EDITION,

WRITTEN BY THE AUTHOR.

Whilst the antiquities of Rome, Greece, and Egypt have been carefully examined and systematically described by English writers, the primeval national antiquities of the British islands have never hitherto been brought into a scientific arrangement. The consequence has been that they have neither furnished those results to history, nor excited that interest with the public in general, which they otherwise would have done. This want of systematic arrangement has probably arisen from the circumstance that on the British islands there exist remains of many different people, as the Celts, the Romans, the Saxons, the North-men and the Normans. It is often difficult to distinguish with certainty the antiquities of those different people, and hence the same remains have, by some authors, been called Celtic or Druidical, by others Roman, by others again Danish, &c.

In order to determine with any degree of certainty the differences between the antiquities of different people, and particularly in order to determine what remains are not Roman, it will evidently be serviceable to British antiquaries to look to the national antiquities of countries that were never conquered by the Romans, and whose national remains are therefore unmixed. In that respect the primeval antiquities of Denmark are peculiarly important. Denmark was peopled at a very early age; it lay beyond the pale of Roman conquest; and there the ante-Roman civilization was kept up to a much later period than in the south and west of Europe. The Royal Museum of Northern Antiquities of Copenhagen contains a greater number of primeval antiquities, than most other collections, and by the efforts of C. J. Thomsen, (the real founder of the Museum,) it has been systematically arranged. The close connection which in the old time existed between Denmark and the British islands, renders it natural that British antiquaries should turn with interest to the antiquities of Denmark, and compare them with those of their own countries.

The present little work, which gives a short review of the Danish antiquities compared with the other antiquities of Scandinavia, was originally written in Danish for a Copenhagen society for the diffusion of useful knowledge[1]. It was not my plan to write a book merely for the archæologist, but more particularly for the general reader. I endeavoured to prove the use and importance of archæological researches, by shewing how the early history of our country can be read through the monuments, and I wanted in that way to excite a more general interest for the preservation of our national remains.

In the supposition that this little book would be acceptable to English readers, my friend Mr. Thoms had already, without my knowledge, translated it into English before my arrival in England, and Mr. Parker had undertaken the publication. But since its publication I have had an opportunity of picking up a good deal of new information by examining the national antiquities of several foreign countries, and last year I published some of the results at which I had recently arrived in another book[2]. Both Mr. Thoms and Mr. Parker agreed with me, that it would be desirable that the English edition should be corrected and enlarged with some of my new observations. I have therefore made a good many alterations, and additions, particularly in the general historical review. I have brought in more information about the connection between the antiquities of our country with those of Germany, Switzerland, France, &c., which, as I hope, will be found to possess some interest. It is only through a comparison of the national antiquities of the different European countries that we shall be enabled to trace the large historical results.

British Archæology has suffered very much from the want of a fixed nomenclature. This has caused a great deal of confusion. The same names and terms have been used for the most different remains. Mr. Thoms and myself have been anxious to give more fixed names. For instance, in the following work the term cromlech has only been applied to the monuments of the stone-period; and the name celt has not, as before, been given alike to stone hatchets, stone hammers, and to two different sorts of bronze hatchets, but only to one sort of bronze hatchet which is commonly called so on the continent, &c. I think that antiquaries can scarcely pay too much attention to the introduction of a fixed terminology.

From the many valuable and interesting notes about similar remains in England, which have been added by Mr. Thoms from the writings of other antiquaries, it will appear, that there exists a great similarity between the Danish and the British antiquities. The same division of the antiquities into three classes,—those belonging to the periods of Stone, and Bronze, and Iron,—which has been adopted in the arrangement of the Danish primeval monuments, will apply to the British remains; and very nearly the same results, in regard to the state of civilization in the stone and bronze periods, as have been gained for Denmark, will also be gained for Britain through a careful examination of its primeval antiquities. At the same time it is perfectly clear, that the British antiquities, when once sufficiently collected, examined and compared, will on the whole give more interesting and important results, than have been derived from those of Denmark, or of most other countries, because they belong to so many and such different people. I myself in my travels in Holland, Ireland, and England, have seen how many most interesting antiquities and monuments still exist in those countries; and I am fully convinced, that a systematical description and comparison of those remains will throw quite a new light upon the early state of the British islands, and particularly that it will present inestimable illustrations on the civilization and connections of the people from the time of the Anglo-Saxons until the invasion of the Normans. It is only through the monuments that we are enabled to trace the influence of the Roman civilization upon the Celts, until it was superseded by those new invaders, who laid the foundation of the subsequent progress of England on the ruins of the Roman civilization. I hope the day is not far distant when the British people will have formed a national museum of antiquities commensurate with the importance of their remains. It is only in that way that they can be enabled to read the history of their country through its national monuments. If my book should have a little of the same effect in England, as that which it was intended to produce in Denmark, viz., to excite a more lively interest in the national remains, I think it will do some good. And even in any case,—if it only shews how important it is that the British and Danish antiquaries should unite their efforts more than has hitherto been the case,—I hope the translation will not be regarded as entirely without use. I feel quite sure that such union could not exist without producing most valuable results for the history of both countries.

J. J. A. WORSAAE,

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

PREFACE

BY

THE EDITOR OF THE ENGLISH EDITION.

In the Preface which the reader has just perused, my learned friend Mr. Worsaae has so well described the object of his valuable little work—of which the present must be regarded rather in the light of a new edition than a translation—that any Preface from me, as its English editor, might at first sight appear altogether uncalled for.

In justice to myself however I feel it right to direct the reader's attention to one or two matters in connection with the present publication.

In the first place, I would briefly explain the motives which induced me to undertake the production of an English version of a work, upon a subject so remotely connected with the branch of antiquarian research to which my attention has been more particularly directed; and, as this explanation may, I trust, not only justify me in what I have done, but tempt others to a further examination of the illustrations of our national antiquities which are to be found in the writings of continental antiquaries, I hope I shall not be considered presumptuous if, in the next place, I venture to point out some mines of information which I think calculated to reward those who will take the trouble to explore them.

In the summer of 1845 my attention was accidentally drawn to the German or second edition of the present work. I had not turned over many of its pages before I felt that the combined knowledge and common sense of the writer had enabled him to produce a more satisfactory book upon a subject involved in very considerable obscurity than it had ever before been my good fortune to meet with. In the belief that it was a book likely to facilitate the enquiries, and to reduce into somewhat of a method the researches, of our English archæologists, in the imperfectly developed field of primeval antiquities, I ventured to recommend it to their attention in a short review which was inserted in the Archæological Journal.

The appearance of that notice having led to the expression of an opinion on the part of many friends, to whose judgment in such matters I could not but defer, that the publication of an English version of Mr. Worsaae's book would be rendering good service to the cause of archæological research, and Mr. Parker having consented to undertake the charge of it, such a publication was determined upon.

Other and more important occupations had occurred to delay the progress of the work, when Mr. Worsaae's visit to this country—a visit which will long be remembered with satisfaction by those who had the opportunity of meeting him—secured me the pleasure of his personal acquaintance, and obtained for the work the benefit of such a thorough revisal by himself, together with such copious additions, as to make it almost a new book instead of a new edition. Its value has not, I trust, been diminished by my endeavour, in the notes for which I hold myself responsible, to make the early national antiquities of Denmark and of this country mutually illustrative of each other. And here it may be very properly explained that the great delay which has taken place in the appearance of the present work has partly had its origin in a wish to make it still more complete, by the addition of a copious Appendix pointing out what remains belonging to the Stone, Bronze, and Iron periods respectively have been found in this country, and the localities in which they were discovered; but the difficulty of securing perfect correctness in the returns of such discoveries, and the length of time necessary to authenticate their accuracy, have necessarily led to the postponement of what will form a very essential supplement to the present volume.

If I am right in my anticipation that the strong practical common sense view, which Mr. Worsaae takes of the primeval antiquities of his native country, will be as readily appreciated here, as it has already been on the continent, it is clear that the publication of an English edition of his work will serve to sweep away from among us the last traces of the many fanciful theories connected with those remains which are a reproach to English archæology; and that the stone chambers will no longer be spoken of as the altars on which human victims were immolated, and that stone hatchets will cease to be described as the sacrificial knives with which the heathen priesthood shed the blood of their fellow-creatures.

Nor is this the only benefit likely to result from its publication; which will it is hoped lead our antiquaries to look to the writings of their continental brethren for that illustration of their studies which in the absence of positive knowledge is only to be obtained by a comparison of objects found in these islands with those discovered abroad, and described by foreign archæologists. As an instance how such comparisons may be instituted, let us take the case of the Gristhorpe find mentioned in the note p. 96 of the following volume: and which is with one exception, I believe, the only discovery of the kind known to have taken place in England.

This tumulus was opened in the month of July, 1834, by Mr. Beswick, the owner of the estate on which it was situated, and Mr. Alexander of Halifax. At the depth of six feet from the surface the spades struck against a hard substance which proved to be a quantity of oak branches loosely laid together; these being removed an immense log of wood, situated north and south, seven feet long by three broad, presented itself to the great satisfaction of these antiquaries. At one end of the log was what was at first supposed to be a rude figure of a human face, (but this seems very questionable, as may be judged by the following woodcuts,) which circumstance, together with the large size of the log, led the finders to believe that they had discovered one of the Druidical remains of the ancient Britons. On attempting to remove this log on the following morning, it seemed, at first, to have been broken by the force employed; but on the fractured portion being lifted up, it was found to be the lid of a coffin, the lower part still remaining in the clay, containing a quantity of fluid in which a human skull was visible; and on the water being thrown out it was soon found that the coffin contained a perfect skeleton. The bones were carefully removed, the other contents of the coffin examined, the lower part taken up, and the whole conveyed to the Scarborough Museum, where they are now deposited. The coffin proved to have been made from the trunk of an oak—

Ingentem quercum, decisque undique ramis

Constituit tumulo—

roughly hewn at the extremities, and split with wedges. It had been hollowed by chisels of flint about two inches in width, but must have been cut down with some much larger tool, the marks of its strokes being three inches in length. The outer bottom of the coffin was in length seven feet nine inches, and its extreme breadth three feet three inches. In the bottom, near the centre, is an oblong hole about three inches long by one wide, most probably intended to carry off any fluids arising from the decomposition of the body. There is little difference in size between the lid and body of the coffin. No resin appears to have been used to fix the lid. It was merely loosely laid on, and kept in its place only by the uneven fracture of the wood, the broken portions corresponding on each side when brought into their proper situations.

The skeleton found in the coffin was quite perfect and of an ebony colour[3]. The bones are much larger and stronger than those of a more recent date, exhibiting the lines and ridges for the attachment of the muscles with a degree of distinctness rarely if ever witnessed at the present day. But the most remarkable portion is the head, which is beautifully formed and of extraordinary size. The skeleton, which has been articulated, measures six feet two inches, and the interior of the coffin being only five feet four inches accounts for the disordered state in which the lower extremities were found, as they must necessarily have been doubled up so as to admit of being placed within it.

The body, which had been laid on its right side with the head to the south and its face turned towards the rising sun, had evidently been wrapped in the skin of some animal, the hair of which was soft and fine, resembling that of a sheep, or perhaps more nearly that of a goat, but not quite so long, and this skin had been originally fastened at the breast with a pin of horn or bone.

The weapons &c. found in this coffin consist of A. the head of a spear or javelin, formed of brass or some other composition of copper; it was much corroded, and had at the broad end two small rivets used to attach it to a shaft, which from the shortness of the rivets still remaining must have been broad and thin.

B. The flint head of a small javelin.

C. A beautifully formed ornament of either horn or the bone of some of the larger cetaceous tribe of fishes. The under side is hollowed out to receive some other appendage; and there are three perforations on each side for the purpose of fastening it by means of pins. It had probably been the ornamental head of a javelin, of which the metal head had formed the opposite extremity. Its symmetrical form, which would not disgrace the most expert mechanic of the present day, combined with the gloss upon it, gives it quite a modern appearance.

D. and E. rude arrow-heads of flint.

F. An instrument of wood resembling in form the knife used by the Egyptian embalmers, the point not sharp but round, and flattened on one side to about half its length. The opposite extremity is quite round.

G. A pin of the same material as the ornament of horn or fish. It was laid on the breast of the skeleton, having been used to secure the skin in which the body had been enveloped.

H. Fragments of a ring of horn, composed of two circles connected at two sides. It was of an oval form, too large for the finger, and was probably used for fastening sonic portion of the dress.

I. By the side of the bones was placed a kind of dish or shallow basket of wicker work, of round form and about six inches in diameter. The bottom had been formed of a single piece of bark, and the side composed of the same, stitched together with the sinews of animals, which, although the basket fell to pieces on exposure to the atmosphere, are still easily to be observed in the fragments and round the edges of the bottom. Attached to the bottom was a quantity of decomposed matter, the remains, as was supposed, of offerings of food, either for the dead or as gifts to the gods.

K. Laid upon the lower part of the breast of the skeleton was a very singular ornament, in the form of a double rose of riband, with two loose ends. It appeared to have been an appendage to some belt or girdle, but like the basket, it fell to pieces immediately on being removed. It is very uncertain of what it was composed: it was something resembling thin horn, but more opaque and not elastic. The surface had been simply though curiously ornamented with small elevated lines.

L. Lastly, a quantity of vegetable substance was also found in the coffin. It was at first believed to be rushes, and being afterwards macerated, although the greater portion of it was so decomposed that nothing but the fibre remained, in one or two instances the experiment was so far successful as to distinguish a long lanceolate leaf resembling the misletoe, to which plant they most probably belonged; this supposition was strengthened by the discovery of some few dried berries, among the vegetable masses, about the size of those of the misletoe. They were however very tender, and soon crumbled to dust.

We have remarked that this discovery stands almost alone in this country. Let us now therefore turn to an account, unfortunately very imperfect, of a somewhat similar one made at Bolderup near Haderslev, in 1827, the particulars of which are recorded in the third volume of the Nordisk Tidskrift for Oldkyndighed, published by the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Copenhagen. The tumulus in which this primitive coffin was found was celebrated in the traditions of the neighbourhood. According to some of these it was the burial-place of a great hero named Bolder or Balder; and according to others, a light was often seen burning on its summit, which was held to be a sure sign that the mound contained hidden treasures. Some excavations had been made by treasure-seekers in 1827, but after digging to the depth of four or five feet without meeting with any thing, further search was abandoned. After this a farmer in the neighbourhood having occasion to fill up some trenches or hollows on his farm, agreed with the proprietor of the mound for permission to cart away so much earth as he wanted, one of the conditions being, that whatever treasure might be found, should be equally divided between the farmer and the proprietor. At about six feet above the level of the surrounding earth, a small urn of baked clay was found, which almost immediately fell to pieces. This gave fresh hopes of finding the expected treasure: the work was continued, and on arriving at the level of the adjacent lands, the workman came to a heap of small granite stones, about the size of a clenched fist, together with one very large one. On removing these, a large shapeless chest presented itself, which was of course immediately looked upon as nothing less than the expected treasure. According to the account of the finder, it was a work of great labour to remove the stones, and while doing so his foot penetrated through the lid of the chest; when finding that it was full of water he dug a trench from it to allow the water to run off.

His next endeavour was to open the chest, and this he accomplished in a very awkward manner, by thrusting a hand-spike into the hole which his foot had made, and so turning over the lid and breaking it off. By this means a quantity of earth fell into the coffin, but not until it had been seen that it contained various objects laid in some degree of order. Unfortunately no one accustomed to such researches was present, for it was not till some little time afterwards that the news of the discovery reached the Rev. Mr. Prehn, a clergyman in the neighbourhood, to whose care is owing the preservation of the following particulars and the several objects described.

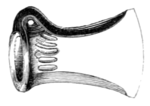

The cist or coffin consisted of a massive oak stem, which had only been roughly hewn and not fashioned into any shape. It exhibited no marks of a saw; and it was obvious that the lid had been formed from the same trunk or stem, in the same way and by the same means. Its extreme length was rather more than ten feet, and the cavity about seven feet long and two broad. At the western part of it there lay in the water (A) a cloak, which took up about half the length, formed of a very peculiar material, being made of several layers of coarse woollen stuff which were sewn together. On the outer edge was sewn a sort of fringe, which consisted of a number of short, fine, black threads, each with a knot at the end. This is altogether very peculiar, and the cloak must have been very thick. Some fragments of it have been preserved in the Museum at Copenhagen. By this cloak there lay (B) some long locks of brown human hair, and by the side of these (C) a bronze sword with a tongue-handle of the same metal; the handle had seemingly been of oak, but it had perished. The sword was of the usual form and size; and the handle had been fastened to it by rivets in a half circle. (D) a dagger also of bronze, the handle which had been fastened to it by rivets was lost. (E) a paalstab of bronze in most excellent preservation, and ornamented on its sides with lines and zigzags. Of the wooden handle which is known to belong to this kind of tool or instrument, there was nothing to be seen. (F) a bronze fibula of the kind commonly found in old grave-hills, the plate being formed of a circular piece of twisted metal, and the pin straight. It is not known in what part of the coffin it lay originally, as it was not seen at first. It is asserted that there was also found at the western end of the coffin, by the side of the locks of hair already mentioned, a comb, resembling in its general appearance those usually found in the northern grave-hills, but what is extremely unusual, it is of horn. It is ornamented with perforations and flame-like incisions. At the eastern end of the coffin a vessel of wood was discovered, which fell to pieces as it was being lifted out of the water with a spade, but in which nothing was found upon a subsequent examination except that there appeared something which looked like ashes on the bottom of it. This vessel was round, about a foot in diameter, and had two ears on the sides. It is somewhat remarkable that this oak trunk, which had been so hollowed out that it would readily have held the body of a full-grown man, should not, apparently, have contained any traces of a human skeleton. But looking to the parties by whom it was discovered, and the peculiar notions they have upon such matters, it is suspected the remains had been removed and secretly interred again, probably in some churchyard[4].

Nor is this Danish account of the discovery of an interment in a tree coffin, the only one which exists to illustrate the Gristhorpe find. For it appears by two passages in the recently published Geschichte der Deutschen Sprache, by Jacob Grimm, that there has lately been a remarkable find at Lupfen near Oberflacht in Suabia, of the so-called Todtenbäume, that is to say, of stems of oaks which have been hollowed out for the purpose of being used as coffins, and which he says not improbably belonged to the times of Alamannic heathendom, possibly to as early a period as the fourth century. The particulars of this discovery have been made known by the Wurtemburg Antiquarian Society, but unfortunately I have not succeeded in obtaining a sight of the book in which they are recorded. This I the more regret, as it is obvious from the mention which Grimm makes of the various articles of wood found at the same time, such as the death-shoes, (the German Todten Schuh, the Helskô of the old Norsemen,) the symbolical wooden hands, and a musical instrument somewhat resembling a violin, that this discovery is calculated to throw great light upon ancient funereal rites[5], and upon the mythology on which those rites were founded.

The reader need scarcely be reminded that these death-shoes were laid by the side of the corpse on account of a popular superstition formerly very prevalent, of one form of which Aubrey has left us a curious record in the remarkable Yorkshire dirge so frequently printed[6]. He tells us that this superstition had its origin in the belief which obtained of the souls of the dead "having to pass through a great lande full of thornes and furzen;" and also that the custom of burying the dead in coffins, formed from the hollowed trunks of trees, and shaped like the boats or canoes they had been wont to use, sprung from a belief that in their passage to the realms of immortality the souls of the departed had to cross the waters which divided the world of the living from that of the dead[7].

In the belief that the one instance I have given will serve as well as twenty to prove the position I have advanced, namely, that great results may be looked for from our English archæologists consulting the writings of their fellow labourers on the continent, I will content myself with pointing out some few works which have come under my own observation, and seem to me deserving the attention of those who take an interest in the study of primeval antiquities.

Klemm's Handbuch der Germanischen Altherthumskunde[8] is a small octavo volume, rendered both useful and interesting from its numerous illustrations, and the abundant references in the foot notes to the writings of German antiquaries on every branch of the early antiquities of their country.

More peculiarly local in its specific object, but very useful and valuable from the minuteness of its details, and its faithful illustrations of objects, is the Heidnische Altherthumer der Gegend von Uelzen im chemaligen Bardengaue (Konigreich Hanover) von G. O. Carl von Estorff[9].

Our Celtic antiquaries too would do well to consult the Taschenbuch fur Geschichte und Altherthum in Süddeutschland, edited by Dr. Heinrich Schreiber, of which five volumes have appeared, the first being published at Freiburg in 1839. Dr. Schreiber's learned Essay on the Torc of the Celts, one of many equally valuable papers, would alone satisfy the reader of the great value of this antiquary's labours.

But far more important than any of the works I have mentioned are Mr. Worsaae's own later contributions to archæological science, of which a list wall be found in the subjoined note[10], inasmuch as they contain a fuller development of this accomplished scholar's views than is to be found in the present elementary book.

Nor need the English antiquary confine himself in his search for illustrations of English primeval antiquities to continental authorities alone. For much that is highly curious and valuable will be found in a handsome quarto volume, published last year by the Smithsonian Institution of Washington, under the title Ancient Monuments of the Missisippi Valley, by E. G. Squire, M.A. and E. H. Davis, M.B., a volume strikingly illustrative of the uniformity which exists between the primitive implements of all the varieties of the human race.

Before concluding this Preface, the Editor cannot refuse himself the pleasure of alluding to two valuable contributions towards a more correct knowledge of our early antiquities, which have appeared since he undertook the task of giving an English version of Mr. Worsaae's work. The first of them is Mr. Akerman's very useful Archæological Index to Remains of Antiquity of the Celtic, Romano-British, and Anglo-Saxon Periods, with its numerous and characteristic illustrations; and the second, the Guide to Northern Archæology, by the Royal Society of Northern Antiquaries of Copenhagen, edited for the use of English Readers by the Right Honourable the Earl of Ellesmere, a volume which may to a certain extent be regarded as a companion to the present hand-book. Both works are eminently calculated to establish those more precise and accurate views respecting Primeval Antiquities, which it has been Mr. Worsaae's especial object to promote in the little work which I now submit to the candid consideration of the reader.

25, Holy-Well Street, Millbank, Westminster,

August 11th, 1849.

- ↑ The Danish title is: "Danmarks Oldtid oplyst ved Oldsager og Gravhöie. Udgivet af Selskabet for Trjkkefrihedens rette Brug. Kjöbenhavn. 1843. 8vo. It has also been published in a German translation. "Dänemarks Vorzeit, durch Alterthümer beleuchtet." Kopenhagen, 1844. 8vo.

- ↑ Blekingske Mindesmærker fra Hedenold. Kjöbenham, 1846. 4to. It has lately appeared in a German translation in "Zur Alterthumskunde des Nordens von J. J. A. Worsaae. Leipzig 1847." 4to.

- ↑ This remarkable circumstance was thus satisfactorily accounted for by the Dean of Westminster (Dr. Buckland) in a communication addressed by him to the editor of the Literary Gazette. "The extraordinary, and as far as I know, unique condition of the bones, preserved by tannin, and converted to the colour of ink, had resulted from the tannin and gallic acid which was in the green oak trunk that forms the coffin, and in its very thick bark. The conversion of the flesh into adipocire must have been occasioned by the ready admission of water through the line of junction of the lid with the body of the coffin, or through the hole cut in the bottom. The clay contained in contact with the body probably contained sufficient iron pyrites to afford the sulphate of iron, which uniting with the tannin and gallic acid, have formed, together with the water within the coffin, an ink of precisely the same materials as that in common use."

- ↑ Nordisk Tidskrift for Oldkyndighed udgivet af det Kongelike Nordiske Oldskrift-Selskab. Bd. III. o. 279.

- ↑ The following extract from the article 'Madagascar' in the Encyclopædia Metropolitana, is so curiously illustrative of the present subject, that I cannot refrain from adding it in the shape of a note. "Their funeral rites have a considerable resemblance to those of the Bechwána tribes on the opposite coast of Africa. The nearest relations assemble at the house of the deceased, the men with their heads and beards shorn, the women wearing a cap as a sign of mourning. The corpse is richly ornamented with rings, chains, coral, &c., and wrapped up in its finest clothes. The women dance and bewail alternately, the men perform feats of arms. Others, in an adjoining room, extol the deceased, ask why he died? Whether he had not gold, cattle, slaves enough? And in this wild alternation of lamentation and feasting, the first day of mourning is past. A tree is then cut down for the coffin, hollowed out, sprinkled with the blood of a slaughtered ox or cow, consecrated by prayer, and finally carried, the corpse having been enclosed in it, by six relations of the deceased, to the family burial-place, (amunukŏ,) and deposited outside of the enclosure surrounding it. A fire is made at each corner of the burying-ground, frankincense is sprinkled upon the embers, the head of the family, standing at the gate calls aloud upon each of his ancestors by name, and entreats them to entertain the new comer well; after which the grave is dug, and the corpse interred without further ceremony. In fifteen days' time more sacrifices are made, provisions are placed near the grave, and the heads of the victims are stuck on poles round the tomb."

- ↑ Scott's Minstrelsy; Ellis's edition of Brand's Antiquities; and in my "Anecdotes and Traditions."

- ↑ For much illustration of those curious points in popular mythology, see Grimm's Deutsche Mythologie, (ed. 1844,) p. 190 et seq.

- ↑ Dresden, 1836.

- ↑ Hanover, 1846.

- ↑ 1. Runamo og Braavalleslaget. Et Bidrag sil archæologisk Kritik ap J. J. A. Worsaae. Kjöbenhavn (Copenhagen), 1844. 4to. Med et Tillæg. Kjöbenhavn 1845. og 5 Tavler.

2. Blekingske Mindesmærker fra Hedenold betragtede i deres Forhold til de örrige skandinaviske og europæiske Oldtidsminder af J. J. A. Worsaae. Med 15 lith. Tavler. Kjöbenhavn 1846. 4to.

No. 1 and 2 also translated into German in:

Zur Alterthumskunde des Nordens von J. J. A. W. Leipzig 1847. 4to. mih 20 Tafeln.

3. Die nationale Alterthumskunde in Deutschland. Reisebemerkungen von J. J. A. W. Aus dem Dänischen. Kopenhagen 1846. 8vo. Leipzig bei Rudolph Hartmann.

4. Danevirke, Danskhedens aldgamle Grœndsevold mod Syden ap J. J. A. W. Kjöbenhavn 1848. 8vo.

Translated into German:

Danevirke, der alte Gränzwall Dänemarks gegen Süden, ein geschichtlicher Beitrag zur wahren Auffassung der Schleswigschen Frage, von J. J. A. W. Kopenhagen 1848. 8vo. Verlag von C. A. Reitzel.

![]()

![]() This work is a translation and has a separate copyright status to the applicable copyright protections of the original content.

This work is a translation and has a separate copyright status to the applicable copyright protections of the original content.

| Original: |

This work was published before January 1, 1929, and is in the public domain worldwide because the author died at least 100 years ago.

Public domainPublic domainfalsefalse |

|---|---|

| Translation: |

This work was published before January 1, 1929, and is in the public domain worldwide because the author died at least 100 years ago.

Public domainPublic domainfalsefalse |