Women worth Emulating.

CHAPTER I.

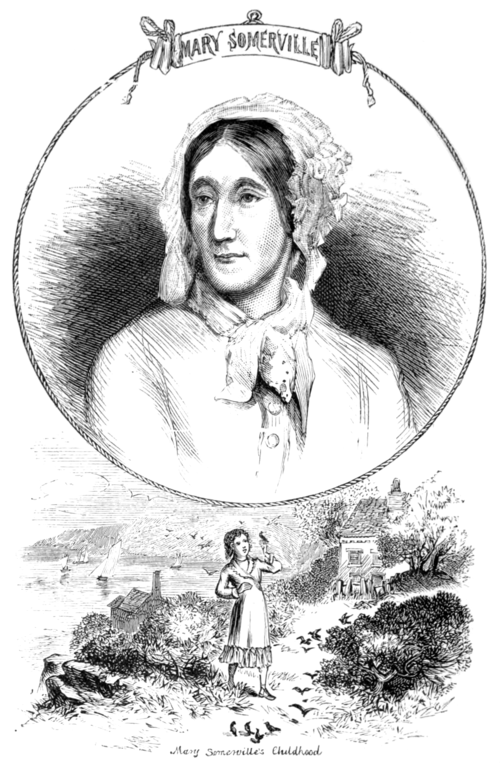

Mrs. Mary Somerville.

he records of biography are not always encouraging to all minds. The talents seem so great, the education and opportunities so advantageous that ordinary readers are apt to say, "Of what use is it that I study such a life? It is quite beyond my range, both in gifts and graces. Coming from the contemplation of anch excellence, or such training, I am not roused but depressed."

he records of biography are not always encouraging to all minds. The talents seem so great, the education and opportunities so advantageous that ordinary readers are apt to say, "Of what use is it that I study such a life? It is quite beyond my range, both in gifts and graces. Coming from the contemplation of anch excellence, or such training, I am not roused but depressed."

This is not by any means a feeling that should be encouraged. There are mental heights we may not ever scale, yet it is well to know of those who have, and in struggling upward we are strengthened even by the effort. As the feeblest climber on a mountainside gets wider views at every step and breathes a more exhilarating air, winning some increase of vigour by the effort, so we dwellers on the more level plain of humanity gain in mental perception and moral force, when we contemplate the recorded progress of those who have gained the lofty heights of scientific investigation, benefited the age, and done honour to womanhood.

One reflection may well reconcile us to the surpassing triumphs of some of whom we read with a humbling sense of our own deficiencies, it is, that however literary and scientific triumphs may—as a general thing, must—be beyond our range and removed from our imitation, there is a path which we all can strive to tread, and where, when we are yet "a great way off," one All-seeing Eye beholds us, one Almighty Hand is stretched out to guide us. Only let us ask from the depths of our heart for help in treading the narrow path that leads to life eternal, and it will surely be given; for "He hath promised who is faithful."

This consolatory, this ennobling thought enables us to delight in all the varied manifestations of excellence with which the Almighty has benefited the world. We praise Him for the beauty He has spread around in the natural world, to lead our thoughts to Him; and still more should we praise Him for the endowments He has given in the human world, to men and women who have lived and laboured and taught among us.

To see God in all things, and to praise Him for all His gifts to mankind, is the hallowed duty and privilege of the young Christian. It is in this grateful frame of mind that we should read of the wise and good; and if, amid much that is beyond our imitation, either in the possession or application of special faculties, yet there should be some sweet lessons of love and duty that come home to the ordinary pursuits and business of life, the interest will be increased, and the teaching of the life more valuable.

In the year 1783 there was a healthy, merry, beautiful little girl of three years old (the daughter of an ancient family) running about on the links at Burntisland, on the coast of Fife, opposite Edinburgh. Though well born, it was necessary that Mrs. Fairfax should live with great economy during the absence of her husband, an officer in the navy, who had nothing but his pay to depend on. In their retirement, therefore, her little daughter had no companions in her own rank of life but an elder brother, who went early to the Edinburgh High School; no luxurious indulgences, and certainly very little attention from servants. She ran about at her own will, and made her own amusements. The child was not fond of dolls or toys, she found her childish pleasures in gathering wild-flowers, wandering on the sea-shore watching the birds, and the sea, and the clouds; she was truly nature's play-fellow, yet always active and willing to be useful. Perhaps the first feeling roused in her infant mind was love for the feathered race, and tenderness to all dumb creatures, of whom she made companions. Some banks of thistles and groundsel that intersected the more cultivated ground at Mrs. Fairfax's abode attracted multitudes of goldfinches and other birds, and a deep love for them sprang up in the child's heart, which remained with her to the end of her long life. Happy the child who early learns to love and protect the animal creation. It is the beginning of good feelings, which soften the heart and elevate the mind.

But little Mary Fairfax, while leading a seemingly very careless childhood, soon began to be useful in household matters. At seven or eight, she pulled fruit for preserving, shelled peas, fed the poultry, and made experiments in bottling gooseberries. She was also taught by her good mother to read the Bible, and to say her simple prayers, morning and evening. Up to ten years of age there could not have been any child among the ranks of the gentry less instructed in all book knowledge. But her physical education was excellent. Plenty of exercise and plain food confirmed her health; and for moral culture, strict veracity and great kindness were the wholesome foundations on which her character was built.

Mrs. Somerville says in her own beautiful and simple biographic sketch,[1] "My father came home from sea and was shocked to find me such a savage. I had not yet been taught to write; and although I amused myself by reading 'The Arabian Nights,' 'Robinson Crusoe,' and 'The Pilgrim's Progress,' I read very badly." Being compelled to read aloud to her father was, she says, "a real penance" to her; but when she was allowed ta help him in his favourite recreation of gardening, she found a pleasure that compensated for her bookish toils. At length Captain Fairfax said to his wife, "This kind of life will never do; Mary must at least know how to write and keep accounts;" and so she was sent off to a boarding-school at Musselburgh. As boarding-schools were then, this was a dreadful change to the poor child. Her lithe little form, straight as an arrow, which had been used to roaming the mountain-side, was soon cased in stiff stays, with steel busk and collar to form her shape (deform it, more likely); a dreary page of Johnson's Dictionary was given her to learn, and dull lessons followed on first principles of writing, and rudiments of grammar. She adds, "The teaching was extremely tedious and inefficient."

You young people of the present day, with your capital books and excellent teachers, need to be reminded of what education was, even for the upper classes, in the days of your immediate ancestors. For this reason I have given you this brief sketch of the early childhood of one who attained the very first ranks among the scientific investigators and benefactors of her age,—an age, be it remembered, eminent beyond all that have preceded it in scientific discoveries and advancement. There have been times when some were mental giants, simply because their compeers were pigmies. That was not the case in the times that produced the Herschels, James Watt, George Stephenson, Davy, Faraday, and a host of others.

The Musselburgh schooldays lasted, fortunately, only a year. At the age of eleven, the illness of Mrs. Fairfax called her young daughter home; and it pained the child's grateful heart that her progress at school was so slight, that when a letter came from a relative she could "neither compose an answer nor spell the words;" and she was reproached for having cost so much—the school terms had been high—and learned so little.

Naturally shy and retiring, no one knew what was passing in the poor little girl's mind; but she well remembered in after-life how she mourned over her ignorance, and how intently she desired to attain knowledge. This was a salutary state of feeling, especially when, as in her case, there was a strong spirit of perseverance; with her, indeed, it was so strong that, in her own very humble estimate of her powers, she always placed perseverance as her greatest characteristic. And, my dear young readers, it is a great truth that what we call "Genius," and talk about vaguely as if it was a something that exonerated its possessor from the need of patient, careful plodding, is in reality the power to take great pains; to go over and over again in some hard study, some toilsome work until it ceases to be hard or toilsome. In mental as in spiritual things, the Scripture maxim applies—

"Patient continuance in well-doing;" that which the word perseverance comprehends, and which is, indeed, the true element of success in all things.

A child who felt her ignorance a sorrow, and whose spirit was of the kind indicated, would soon overcome her difficulties. She did not allow her likes or dislikes to influence her; but with great docility resolved to learn all she could. From her active habits, needlework was not pleasant to her; and an aunt, in Scottish phrase, once said, "Mary does not shew (sew) any more than if she were a man." Nevertheless, she set herself to overcome her repugnance, and became skilful with her needle, both in plain and fancy work.

A piano came to her home, and she began to learn music, which was then very imperfectly taught; but she rose in the morning and practised so sedulously that she speedily gained a facility which her family rejoiced in, for no accomplishment in a country house is more likely to delight a home circle. But, unhappily, the shyness of the young pianist always prevented her in early days doing justice to herself. Meanwhile, she learned to write a good hand, and made some, not great, progress in arithmetic. The little French she had been taught at school she added to by puzzling out and translating from French books, by herself, and so almost insensibly acquired a reading knowledge of the language.

One day, at the house of a friend, as she was looking in a magazine of a fashionable kind for a pattern of ladies' work, she came upon some letters oddly arranged—an algebraic problem. Asking the meaning, she heard the word Algebra for the first time. She thought about the word and took every opportunity that her great diffidence permitted to get further explanation. She was told of the need of arithmetic in the higher branches and mathematics. She thought that some books in the home library might help her, and so she pored over some books of navigation; and though she made very little progress in what she wanted to know, she learned enough to open her mind to the value of solid studies and to interest her in them. Meanwhile, from some elementary books, probably her brother's, she began to teach herself Latin, and with no help of regular instruction learned enough to enable her to read Caesar's Commentaries, and to feel an interest in her reading.

Her habit of early rising was her great help, and enabled her to pursue her studies unmolested. She was very diligent in performing all that she was required to do in her daily domestic avocations, so that no fault could be found with her for neglecting anything required of her in the ordinary pursuits of life. Thus the lonely little student went on with her studies, until her progress was so considerable that when on a visit to her uncle, the Rev. Dr. Somerville, he found she had grounded herself both in Latin and Greek. He gave her books, and what was better, a word of encouragement, and she at length possessed a Euclid, and advanced into mathematics.

The word of encouragement must have been indeed precious from its rarity. She was not only laughed at but censured for the studies she applied herself to; "going out of the female province" was then the common phrase of disapproval. Poor girl! it was to her, as it has been to multitudes in the old times of darkness and prejudice, a strange thing to find that the world recognised ignorance as the female province.

However, she persevered in all gentleness, yet with ceaseless energy. No one could say that she neglected any ladylike acquirements. Her skill with the pencil was so marked that she was permitted to have some good instruction, and she studied under an eminent master in Scotland, attaining such proficiency that her paintings and drawings during her whole life were much admired, and she never, even in extreme old age, entirely laid aside that delightful art. Once in her youth, on her skill being spoken of in the presence of a rather harsh old lady, the latter remarked, with more frankness than politeness, "I am glad that Miss Fairfax has any kind of talent that may enable her to win her bread, for every one knows she will not have a sixpence."

When she grew up and was introduced more frequently into society,—her father having greatly distinguished himself in a naval victory, and gained promotion,—she was much admired, not only for her personal attractions, which were a natural gift, but for the charm of her manners, her sweet voice, and many graceful accomplishments. Of slight figure, small stature, and delicately fair complexion, she looked the embodiment of youth and feminine refinement.

She was naturally much sought after, even though her severe studies and varied attainments were so little understood as to be regarded rather as an eccentricity, merely to be treated with indulgence, as the strange caprice of a lovely girl left much to herself, and allowed to employ her leisure in her own peculiar way.

Mr. Samuel Greig, a connection of her mother's family, and Commissioner of the Russian Navy and Russian Consul for Britain, paid a visit to Admiral and Mrs. Fairfax, which ended in his proposing for the hand of their daughter, and being accepted. Miss Fairfax was then in her twenty-fourth year, and the preparations for her marriage were made on a scale of economy very unusual in her rank in these extravagant days. She says, "Fortune I had none, and my mother could only afford to give me a very moderate trousseau, consisting chiefly of fine personal and household linen. When I was going away, she gave me twenty pounds to buy a shawl or something warm for the winter. I knew that Sir Arthur Shee, of the Academy of Paintings, had painted a portrait of my father immediately after the battle of Camperdown, and I went to see it. The likeness pleased me; the price was twenty pounds; so, instead of a warm shawl, I bought my father's picture."

It is pleasant to read that soon after she had warmed her heart by possessing this treasure, she had a gift of furs presented to her by her husband's brother.

In many sketches of this lady's life it was said that her first husband directed her studies, and aided her in what became her favourite pursuits. This was very generally received and repeated as a truth; but in the work on her mother's life, by Miss Martha Somerville, this is positively contradicted. Mr. Greig is said not to have admired learning in women, and that he loved his charming wife in spite of, and not for, her intellectual attainments. The entire absence of all assumption, her manners and conversation, disarmed the prejudice which then was felt at any unusual mental gifts.

It is noticeable that in every period of her life this lady was a learner. I think that is why she kept her faculties so bright through the long life that was granted her. When a young bride in London, she took the opportunity of obtaining lessons from a French lady, and perfected herself in that language. Afterwards she studied German and Italian, and all this with the motive of reading the works of scientific men in those languages.

Her married life lasted only three years, and she was left a widow, with two little sons, at the age of twenty-seven. Shattered in health by her trials, she returned to Scotland to her parents' house, and found consolation in the care of her children, and after a time, in pursuing her studies. As she was now independent, no one could prevent her so employing herself in her retirement, and for five years she continued her scientific researches. There were none to praise—that she did not require, knowledge being to her its own reward; but there seem to have been many to wonder and to blame. However, her kind uncle, the Rev. Dr. Somerville, who had first shown his sympathy with her tastes and pursuits, always stood her friend; and his son, a medical man, became her second husband in 1812, to the great joy of most of the family.

The following, showing the rudeness that prejudice sometimes engenders, is recorded in Mrs. Somerville's biography: "I received a most impertinent letter from one of his (Dr. Somerville's) sisters, who was unmarried, and younger than I, saying she hoped I 'would give up my foolish manner of life and studies, and make a respectable and useful wife to her brother'" This strange presumption, though it was freely forgiven, yet created a coldness and reserve ever after.

It was a singular fact in the history of Mary Fairfax that she was born at her Uncle Somerville^s house, and Mrs. Fairfax being extremely ill, she was taken by her aunt, who had an infant at the time, and nursed by her, and was ever regarded as a daughter of the house before she formed the marriage which made her so.

The Rev. Dr. Somerville, speaking of his son's marriage, says, "Miss Fairfax had been born and nursed at my house, her father being abroad at the time on public service. She afterwards often resided in my family, was occasionally my scholar, and was looked upon by me and my wife as if she had been one of our own children. I can truly say, that next to them she was the object of our most tender regard. Her ardent thirst for knowledge, her assiduous application to study, and her eminent proficiency in science and the fine arts, have procured her a celebrity rarely obtained by any of her sex. But she never displays any pretensions to superiority, while the affability of her temper and the gentleness of her manner afford constant sources of gratification to her friends."

The marriage proved in all respects happy. Dr. Somerville entered with zeal into all his wife's studies; indeed, he was himself devoted to scientific pursuits, both in his profession as a physician and in his leisure hours. He was a tender and generous step-father to the one surviving son of his wife's first marriage. There were three daughters of the second marriage—Margaret, Martha, and Mary. The first, to her parents' great grief, died in early life; the two latter survived to be the tender ministers to their mother's declining years, her literary helpers, and biographers.

The life of Mrs. Somerville, from the time of her second marriage, is but a happy record of her scientific achievements; and the publication of her valuable books. One trouble came—a loss of fortune, which compelled them to remove from their house in Hanover Square, and made Dr. Somerville accept the post of physician to Chelsea Hospital, in 1827, and take up his abode there. The residence never suited Mrs. Somerville's health, but she employed herself with characteristic perseverance and cheerfulness.

In 1831, she brought out her "Mechanism of the Heavens." This was followed by her chief work, "The Connection of the Physical Sciences," which ran through several editions, and became a class book at our universities.

I cannot refrain from mentioning that I met with that book in a very remote region. At the little town of St. Just, at the extreme west point of England, near Cape Cornwall, a Literary and Mechanics' Institution was built, which I visited in 1850. Being shown into the library, I took up a book that was lying on the table, and found it was "The Connection of the Physical Sciences," and its worn binding and well-thumbed pages bore evidence of its having been largely circulated amongst working-class readers. I thought it a great tribute to the value of the book, and equally an evidence of the intelligence of Cornish working-men.

After some years, these first works were followed by her "Physical Geography;" and when old age had settled down upon her, she wrote "Molecular and Microscopic Science." Honours came from foreign lands, as well as from learned Societies at home. She was elected Honorary Member of the Royal Geographical Society, the same year that a similar honour was conferred on Miss Caroline Herschel, the sister and aunt of the two eminent astronomers Sir William and Sir John Herschel—herself no less eminent. The Royal Theresa Academy of Science elected Mrs. Somerville a member; and Geographical Societies, both in Britain and on the Continent, enrolled her honoured name in their lists.

Her correspondence was very large with all the eminent literati of her time, and she enjoyed the friendship of the distinguished men and women who made the intellectual society of the age.

A pension of two hundred pounds a year for her life was well bestowed during Sir Robert Peel's time of office; and, her health requiring change, she went to the Continent with Dr. Somerville and their daughters. After making many excursions to different cities and kingdoms, the family finally settled down in Italy. At Rome, Florence, Naples, and Geneva, Mrs. Somerville in turn resided, always actively employed in every good work—the anti-slavery question, the freedom and unification of Italy, the abolition of the horrors of vivisection, as practised by foreign surgeons under the specious name of scientific investigation, and, alas! coming into our own Schools of Anatomy. Ever this detestable cruelty found in her a stern opponent. Education for the poor, and especially a more liberal education for women, called all her energies into exercise long after she had reached her eightieth year.

Her beloved husband, full of years and honours, passed away some time before her own death; but though bereaved and stricken, she was patient and resigned. Her daughters were not only her children, but her companions and friends—one in heart and mind. So years passed on, not withering, but ripening all the hallowed graces of the mind and soul in Mary Somerville. Though she lived to be ninety-two, it can scarcely be said that she ever lost her youth, her intelligence remaining so clear, her spirits so fresh, her sympathies so active. Able to read without spectacles, to write to and converse with her friends; a slight deafness and a little tremor of the hands alone told that the vital energy was flagging, while her soul was light in the Lord. On principle, she said but little on her religious opinions, and never entered into controversy; but she was deeply and truly devout. One of her last written testimonies was: "Deeply sensible of my own unworthiness, and profoundly grateful for the inumerable blessings I have received, I trust in the infinite mercy of my Almighty Creator. I have every reason to be thankful that my intellect is still unimpaired; and although my strength is weakness, my daughters support my tottering steps, and by incessant care and help make the infirmities of age so light to me that I am perfectly happy."

Surely Goldsmith's beautiful simile may be applied to this venerable lady,—

"As some tall cliff that lifts its awful form,

Swells from the vale, and midway leaves the storm;

Though round its breast the rolling clouds are spread,

Eternal sunshine settles on its head."

Without pain or illness, she placidly sank and died in her sleep, on the morning of November 29th, 1872. She was buried in the English Campo Santo at Naples. The full history of a life so long and so active would be the history of an age. She had known all the troubles, wars, and political contests of the latter part of the reign of George III.; the Regency; the corrupt reign of George IV.; the better times of King William IV. and his amiable Queen Adelaide, who honoured Mrs. Somerville with kindly appreciation; the accession of Queen Victoria, our beloved sovereign, whose studious youth had been familiarised with Mrs. Somerville's writings, and whose mental attainments, we know, make her interested in promoting the knowledge of science and literature among all her subjects. Such an indefatigable life, such a genial old age, and such a peaceful death, are the lot of few; but we who can but look with admiration on such talents may emulate and imitate her virtues.

- ↑ * See introduction to the life of Mrs. Somerville, by her daughter, p. 20.