A Dictionary of Music and Musicians/Te Deum Laudamus

TE DEUM LAUDAMUS (Eng. We praise Thee, O God). A well-known Hymn, called the Ambrosian Hymn, from the fact that the poetry is ascribed by tradition to S. Ambrose and S. Augustine. The English[1] version, one of the most magnificent to be found even in the Book of Common Prayer, appears in the first of the English Prayer-books in the place which it now occupies. The custom of singing Te Deum on great Ecclesiastical Festivals, and occasions of special Thanksgiving, has for many centuries been universal in the Western Church; and still prevails, both in Catholic and Protestant countries. And this circumstance, even more than the sublimity of the Poetry, has led to the connection of the Hymn with music of almost every known School.

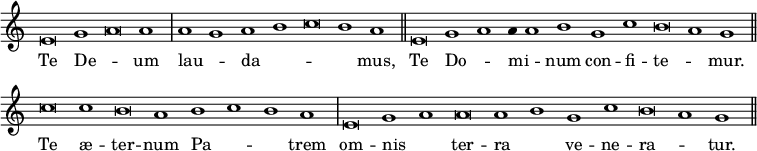

The antient Melody—popularly known as the 'Ambrosian Te Deum'—is a very beautiful one, and undoubtedly of great antiquity; though it cannot possibly be so old as the Hymn itself, nor can it lay any claim whatever to the title by which it is popularly designated, since it is written in the Mixed Phrygian Mode—i.e. in Modes III and IV combined; an extended Scale of very much later date than that used by S. Ambrose. Numerous versions of this venerable Melody are extant, all bearing more or less clear traces of derivation from a common original which appears to be hopelessly lost. Whether or not this original was in the pure Mode III it is impossible to say with certainty; but the older versions furnish internal evidence enough to lead to a strong conviction that this was the case, though we possess none that can be referred to the age of S. Ambrose, or within two centuries of it. This will be best explained by the subjoined comparative view of the opening phrases of some of the earliest known versions.

In all these cases, the music to the verse 'Te æternum Patrem' ('All the earth doth worship Thee') is adapted, with very little change, to the succeeding verses, as far as 'Te ergo quæsumus' ('We therefore pray Thee'), which verse, in Catholic countries, is sung kneeling. The only exception to this is the phrase adapted to the word 'Sanctus' ('Holy'), which, in every instance, differs from all the rest of the Melody.[2] As far, then, as the verse 'Te ergo quæsumus' inclusive, we find nothing to prevent us from believing that the Music is as old as the text; for it nowhere deviates from the pure Third Mode, as sung by S. Ambrose. But, at the next verse, 'Æterna fac' ('Make them to be numbered'), the Melody passes into the Fourth Mode, with a marked allusion to the Fourth Gregorian Tone, of which S. Ambrose knew nothing.

This phrase, therefore, conclusively proves, either that the latter portion of the Melody is a comparatively modern addition to the original form; or, that the whole is of much later date than has been generally supposed. We are strongly in favour of the first supposition; but the question is open to discussion on both sides.

The beauty of the old Melody has led to its frequent adoption as a Canto fermo for Polyphonic Masses; as in the case of the fifth and sixth Masses—'In Te, Domine, speravi,' for 5 voices, and 'Te Deum laudamus,' for 6—in Palestrina's Ninth Book. But the number of Polyphonic settings is less than that of many other Hymns of far inferior interest. The reason of this must be sought for in the immense popularity of the Plain Chaunt Melody in Italy, and especially in the Roman States. Every peasant knows it by heart; and, from time immemorial, it has been sung, in the crowded Roman Churches, at every solemn Thanksgiving Service, by the people of the city, and the wild inhabitants of the Campagna, with a fervour which would have set Polyphony at defiance.[3] There are, however, some very beautiful examples; especially, one by Felice Anerio, printed by Proske, in vol. iv. of 'Musica Divina,' from a MS. in the Codex Altaemps. Othobon., based on the antient Melody, and treating the alternate verses only of the text—an arrangement which would allow the people to take a fair share in the singing. The 'Tertius Tomus Musici operis' of Jakob Händl contains another very fine example, in which all the verses are set for two Choirs, which, however, only sing alternately, like the Decani and Cantoris sides in an English Cathedral.

Our own Polyphonic Composers have treated the English paraphrase, in many instances, very finely indeed: witness the settings in Tallis's and Byrd's Services in the Dorian Mode, in Farrant's in G minor, in Orlando Gibbons's in F (Ionian Mode transposed), and many others too well known to need specification. That these fine compositions should have given place to others, pertaining to a School worthily represented by 'Jackson in F,' is matter for very deep regret. We may hope that that School is at last extinct: but, even now, the 'Te Deum' of Tallis is far less frequently heard, in most Cathedrals, than the immeasurably inferior 'Boyce in A'—one of the most popular settings in existence. The number of settings, for Cathedral and Parochial use, by modern Composers, past and present, is so great that it is difficult even to count them.[4]

It remains to notice a third method of treatment by which the text of the 'Te Deum' has been illustrated, in modern times, with extra-ordinary success. The custom of singing the Hymn on occasions of national Thanksgiving naturally led to the composition of great works, with Orchestral Accompaniments, and extended movements, both for Solo Voices and Chorus. Some of these works are written on a scale sufficiently grand to place them on a level with the finest Oratorios; while others are remarkable for special effects connected with the particular occasion for which they were produced. Among these last must be classed the Compositions for many Choirs, with Organ and Orchestral Accompaniments, by Benevoli, and other Italian Masters of the 17th century, which were composed for special Festivals, and never afterwards permitted to see the light. Sarti wrote a 'Te Deum' to Russian text, by command of the Empress Catherine II, in celebration of Prince Potemkin's victory at Otchakous, in which he introduced fireworks and cannon. Notwithstanding this extreme measure, the work is a fine one; but far inferior to that composed by Graun, in 1756, by command of Frederick the Great, in commemoration of the Battle of Prague, and first performed at Charlottenburg, in 1762, at the close of the Seven Years' War. This is unquestionably the most celebrated 'Te Deum' ever composed on the Continent; and also one of the finest. Among modern Continental settings, the most remarkable is that by Berlioz, for two Choirs, with Orchestra and Organ obbligato, of which he says that the Finale, from 'Judex crederis,' is 'without doubt his grandest production.' Of this work (op. 22) nothing is yet known in England; but it was performed at Bordeaux, Dec. 14, 1883. [App. p.798 "add that Berlioz's work was performed at the Crystal Palace, April 18, 1885, and by the Bach Choir, May 17, 1887. The latter body sang the work again, with several anthems, etc., in Westminster Abbey June 28, 1888, the Jubilee of Her Majesty's coronation."] Cherubini, in early youth, wrote a Te Deum, the MS. of which is lost; but, strangely enough, his official duties at the French Court never led him to reset the Hymn.

But the grandest Festal settings of the 'Te Deum' have been composed in England. The earliest of these was that written by Purcell for S. Cecilia's Day, 1694; a work which must at least rank as one of the greatest triumphs of the School of the Restoration, if it be not, indeed, the very finest production of that brilliant period. As this work has already been described in our account of that School,[5] it is unnecessary again to analyse it here. It is, however, remarkable, not only as the first English 'Te Deum' with Orchestral Accompaniments; but also as having stimulated other English Composers to the production of similar works. In 1695, Dr. Blow wrote a 'Te Deum,' with Accompaniments for 2 Violins, 2 Trumpets, and Bass—the exact Orchestra employed by Purcell; and, not long afterwards, Dr. Croft produced another work of the same kind, and for the same Instruments.

The next advance was a very important one. The first Sacred Music which Handel composed to English words was the 'Utrecht Te Deum,' the MS. of which is dated Jan. 14, 1712.[6] Up to this time, Purcell's Te Deum had been annually performed, at S. Paul's, for the benefit of the 'Sons of the Clergy.' To assert that Handel's Te Deum in any way resembles it would be absurd: but both manifest too close an affinity with the English School to admit the possibility of their reference to any other; and, both naturally fall into the same general form, which form Handel must necessarily have learned in this country, and most probably really did learn from Purcell, whose English Te Deum was then the finest in existence. The points in which the two works show their kinship, are, the massive solidity of their construction; the grave devotional spirit which pervades them, from beginning to end; and the freedom of their Subjects, in which the sombre gravity of true Ecclesiastical Melody is treated with the artless simplicity of a Volkslied. The third—the truly national characteristic, and the common property of all our best English Composers—was, in Purcell's case, the inevitable result of an intimate acquaintance with the rich vein of National Melody of which we are all so justly proud; while, in Handel's, we can only explain it as the consequence of a power of assimilation which not only enabled him to make common cause with the School of his adoption, but to make himself one with it. The points in which the two compositions most prominently differ are, the more gigantic scale of the later work, and the fuller development of its Subjects. In contrapuntal resources, the Utrecht Te Deum is even richer than that with which Handel celebrated the Battle of Dettingen, fought June 27, 1743; though the magnificent Fanfare of Trumpets and Drums which introduces the opening Chorus of the latter, surpasses anything ever written to express the Thanksgiving of a whole Nation for a glorious victory.[7]

The Dettingen Te Deum represents the culminating point of the festal treatment to which the Ambrosian Hymn has hitherto been subjected. A fine modern English setting is Sullivan's, for Solos, Chorus, and Orchestra, composed to celebrate the recovery of the Prince of Wales, and performed at the Crystal Palace. A more recent one is Macfarren's (1884).

- ↑ In one verse only does this grand paraphrase omit a characteristic expression in the original—that which refers to the White Robes of the Martyrs:

'Te Martyrum candidatus laudat exercitus.'

'The noble army of Martyrs praise Thee.'The name of the translator is not known.

- ↑ Marbecke, however, makes another marked change at 'Thou arte the Kyng of Glorye.'

- ↑ An exceedingly corrupt excerpt from the Roman version—the verse 'Te æternum Patrem'—has long been popular here, as the 'Roman Chant.' In all probability it owes its introduction to this country to the zeal of some traveller, who 'picked it up by ear.'

- ↑ A second setting in the Dorian mode, and a third in F, by Tallis, both for 5 voices, are unfortunately incomplete. [See p. 54.]

- ↑ See vol. iii. pp. 284–285.

- ↑ Old Style; representing Jan. 14, 1713, according to our present mode of reckoning.

- ↑ For an account of the curious work which, of late years, has been so frequently quoted in connection with the Dettingen Te Deum, we must refer the reader to the article on Urio, Dom Francesco.