Archaeological Journal/Volume 5/On the Norman Keep Towers of Coningsburgh and Richmond

ON THE NORMAN KEEP TOWERS OF CONINGSBURGH AND RICHMOND.

It may perhaps have an appearance of singularity to speak of the application of the principles of induction, first duly appreciated by Bacon, to a subject like that of antiquity, which is followed more as an amusement than a study. But if the prosecution of truth after some certain order, consonant with the nature of our understanding, be found advantageous in higher subjects, it is not methinks unreasonable to suppose that even lighter matters, if worth following at all, are worth following after some correct and definite plan, i. e. by means of a systematic generalization from particular examples. And that this remark is well founded, may perhaps be gathered from the consideration of the rapid progress which the study of antiquity has made within the last few years, particularly that branch of it connected with architecture. For now that antiquaries have ceased to wander through the regions of imagination, and search for arguments wherewith to support some baseless fabric of a vision raised on a groundless conjecture, much valuable information has been gathered on the history of by-gone days. Substantial and well-founded evidence is presented to us in the shape of drawings, plans and careful descriptions, from which we may safely draw inferences, and compensate by the sureness of our conclusions for the apparent slowness of our progress. In this point of view, every new example, every simple fact, however humbly presented to view, (provided it be correct,) has its value; and it is with this conviction that the writer of the present article ventures to offer some remarks upon the Norman keep towers of Coningsburgh and Richmond, in Yorkshire; accompanying them with plans drawn by the eye upon the spot, and checked by measures so as to insure a tolerable approximation to accuracy. The writer however does not pretend to offer finished surveys, or to claim minute accuracy for the details, such as the exact width of walls or doorways, the splays of windows, &c. Before proceeding to the description of particular examples, it may perhaps be allowable to offer a few remarks on the arrangement of Norman castles generally. These are collected from a comparison of English examples, with the accounts of those still existing in Normandy. The nature of Norman fortresses is perhaps more definite than that of later erections, by reason of its greater simplicity; for in after times, military architecture was accommodated more to the conveniences of life, and a compromise was thus made as to the form and arrangement of castles. In various strong positions throughout this country we find, as in Normandy, many deeply entrenched earth-works, which, though attributed to the Danes, may in many instances be more correctly ascribed to the ninth or tenth century, or even a much later period. Instances among others occur at Builth, South Wales, where the two moats and the motte or keep-mound are in their original state, but with no remains of masonry; also at Longtown, at the foot of the Black Mountains, Herefordshire, where the motte and circular keep remain, and again at Kilpeck, in the same county, are extensive earth-works with the masonry destroyed. The origin of this castle is historically recorded, and the account given at length in Lewis's Kilpeck Church. I may mention a fourth, perhaps earlier, at Laughton-en-le-Morthen, near Doncaster, East Yorkshire, consisting of an outer ballium, and a lofty motte, but without any traces of masonry. Close adjacent is the church, exhibiting manifest traces of Saxon architecture. My note-books, if I had time to search them, would I doubt not present several other examples; the fortifications of Old Sarum are also an example. The classification of the different descriptions of earth-works, which are found in almost countless numbers throughout the country, has not yet been properly undertaken, although I think offering an interesting field for investigation, particularly if regarded in connection with similar remains in other countries. As regards our present subject—Norman fortresses—some assistance may be derived from a comparison with those of Normandy.

The earliest military works seem to have been derived from the forts erected by the Romans in their distant provinces. In the time of Justinian we read of castles strongly posted on commanding heights defended by precipices and deep ditches; with battlements, machicolations, portcullisses, and galleries in the thickness of the walls. The keeps of our Norman castles seem to be the probable representatives of the Roman prætoria. And here I may mention the singular occurrence of one of the Welsh conical mounds, called 'Tomens,' in the midst of an undoubted Roman camp, at Castell-Tomen-y-mûr, near Festiniog, North Wales.But to proceed to the general character of the fortresses of Normandy, as common to those of England. Those of earliest date which were of small size, consisted of an enclosure of about half an acre, sometimes as much as an acre, which was surrounded by an exterior ditch and an agger within, sur- mounted by a vallum or palisade of stakes. Sometimes, where stone could be readily procured, a wall supplied the place of the palisade. At one end of the enclosure, sometimes in the centre, stood a high conical mound of earth, of from twenty to forty feet in elevation, called by the French antiquaries, la motte, and intended for the support of the donjon or keep. There is reason to suppose that this was originally of wood, as many of the mounds are not calculated to support a structure of stone, unless the foundations had been carried through to the natural level of the ground, which in later instances is, I understand, found to be the case. The donjon was sometimes square, sometimes round; when constructed of stone there is reason to think that the circular form was adopted chiefly at a later period. The castles of the twelfth century exhibited as their chief improvements, two ballia or courts instead of one; flanking towers along the exterior walls; a barbican or outwork in front of the main entrance, as at Old Sarum; and the revival of the portcullis. In other respects the plan remained the same, although the scale and execution was of a superior description[1].

I will now add a few observations from the examples of Norman architecture which I have examined in different parts of England.

Position of the motte and keep tower. There are two types of keep towers, of which Coningsburgh and Richmond may serve as specimens; the one round, the other square. Of these the circular keep often, perhaps generally, stands on a mound or motte, while the square form is, as far as I am aware, always without it. The keep is very frequently found in the side of the enclosure, or of the innermost court if there are two. The mottes of Longtown, Herefordshire, Laughton-en-le-Morthen, Yorkshire, and Carisbrook, Isle of Wight, (?) are in the circuit of the wall; that of Tutbury, Staffordshire, and Pevensey, Sussex, are close to the outer wall; the keeps of Porchester and Goodrich form a part of the enclosure, as do both the subjects of the present paper, and the circular keep of Barnard Castle, Durham. The keep of Rochester is very near the boundary wall, while the mottes of Builth and Cardiff are nearer to one side of the area than the other. Sometimes walls pass from the keep to the boundary wall, so as to cut off a separate area, as at Pickering, Yorkshire, and Tretwr, Breconshire. The ground-floor of keeps is, I believe, almost universally devoted to the purposes of a store room, perhaps of a dungeon, and the entrance is at the first floor either by a door in a projecting tower, with an inclined ascent and draw- bridge, as at Newcastle, Rochester, and Loches in France, (which from the drawings which I have seen, remarkably resembles Rochester,) or the door is in the body of the building, and approached by steps either permanent or moveable. There was sometimes an independent entrance to the ground-floor, as at Newcastle and Bamborough, Northumberland, and Richmond, where it is by far the grandest. At Barnard Castle and Pontefract, Yorkshire, (which must be, I think, a Norman keep,) are sally-ports descending through the thickness of the wall and the rocks on which those keeps stand. This is also the case at a Norman tower, Pevensey, Sussex. The mode of approaching the various rooms varies in different castles. In square keeps we find circular staircases at one or more of the angles, from which, on the level of each floor, galleries are carried through the thickness of the walls, as at Rochester. In small keeps these galleries are not required. At Goodrich the circular staircase is the means of approach. At Dover is a very large staircase of this kind beautifully constructed. Frequently the stairs are straight, and formed in the thickness of the wall, as at Richmond.

In circular keeps the staircase is sometimes in an attached and partially entering turret, as at Skenfrith; sometimes curving up the thickness of the wall, as at Launceston, Coningsburgh, Barnard Castle, Durham, and Brynllys, Breconshire. In the last example the doors open from the window sills. At Llanbadarn tower, at the entrance of the magnificent pass of Llanberris, North Wales, the staircase is peculiar; it is a circular stair in the thickness of the wall, commencing on the right of the entrance, and about half way up turning aside, and continuing nearly over the door. At Tretwr, there is a curious return in the staircase, so that it ascends over the entrance door[2].

Coningsburgh castle, one of the subjects of my communication, is situated on the summit of a considerable elevation, partly isolated by art, at a very short distance from the town, in the direction of the navigable river Dun. Its lofty keep (to which I confine my observations), rising picturesquely above the dense shade of surrounding trees, commands a beautiful view over the neighbouring country, and along the valley; and forms from far a conspicuous object. The base of the hill is surrounded by a deep ditch, the sides of which are steeply scarped, especially on the north-east. The summit, which is of some extent, is surrounded by a wall, enclosing an area of an irregular oblong form. At one extremity of this, built into the surrounding wall, is the massive and lofty keep tower of cylindrical form, flanked by semi-hexagonal turrets or buttresses of unusually massive character. The approaches to the castle appear to have been two; the main entrance towards the north-west, and a postern on the north-east, close adjacent to the keep which commands it. To the south-east, not very far below, runs the present turnpike road. In approaching by the principal entrance, the ditch, which is at a considerable distance from the walls, is crossed by a narrow raised causeway, whence a narrow passage between very high walls conducts directly up to the foot of one of the octangular towers, which flank the north-west extremity of the area. Here it turns to the right under the wall of the fortress, and separated from the ditch by another wall. Unfortunately the south-west side of the area is so far destroyed, that the foundations could not be made out without considerable difficulty. It will be seen that the entrance is remarkably strong, being completely commanded by the tower and wall.

The two flanking towers, one of which has just been mentioned, rise boldly on the edge of the abrupt slope; they batter considerably, and are very strong and massive, without windows, having no entrances as far as I could perceive from the ground level. These however might have been from the parapet of the boundary wall, and not observed by me in my hasty survey of this part.

The postern is very remarkable from its contrivance and strength. A narrow arch leads vaulted passage, the direction of which is away from the keep. Its communication with the interior is now blocked up, but I give a plan of it, from King's Munimenta Antiqua, and one of the castle from the Gentleman's Magazine for 1802, part I.There are no windows to be seen in these walls, save one, somewhere to the north, of the circular form. Here also there is a large breach in the wall, shewing the thickness to be about six feet. Along the steep slope of the north-west side, the wall batters slightly, and is flanked by straight square buttresses, slightly projecting and giving evidence of Norman construction.

The fine and lofty circular Norman keep is partly built into the north-east wall, towards the south-east extremity of the area. I estimated its height at sixty feet from the ground, exclusive of the turrets, which may be ten more, judging from the number of steps in the staircases. By some, the greatest height of the turrets is stated at ninety feet. The walls batter slightly, and are fifteen feet in thickness at the base, while at the summit, partly from the recession of the upper floors, and partly from the battering, their thickness is barely ten feet. Six semi-hexagonal buttresses strengthen these massive walls, and rise at the summit in the form of turrets. The base of the keep, as in many Norman buildings, slopes outwards so as to form a high plinth. The whole is faced with cut stone, and presents an admirable specimen of masonry. The space between the two north-east turrets forms a part of the boundary wall, and advantage is taken of this circumstance to place the two garderobes of the castle on this side, so that their discharges do not affect the interior of the area.

The entrance (A) is by a large door, twelve or more feet from the ground, according to the usual plan; its massive square lintel is surmounted by a semicircular strengthening arch. The door is on the south side, and is sheltered by the close proximity of the boundary wall; the steps leading up to it are of modern date, and the means of access were probably of wood, and capable of removal. It may be observed however, that at the foot of the present steps, and more towards the corner formed by the junction of the boundary wall, there are traces of circular foundations.The exterior of the castle is as plain as it can well be, for exclusive of loop-holes, and two small quatrefoils in the chapel, there are only two windows in the building; one of these (C) is over the door, and belongs to the chief room. It is divided into two lights by a large stone pillar, and has massive lintels surmounted by a semicircular arch for strength. In the floor above this is a similar but smaller window (K) between the first and second left turrets[3].

As a hint for those who may attempt to plan the floors of castles, it may be well to observe that the accompanying ground-plans could not have been rendered worthy of any reliance, had I not been careful to note down the positions of all the loop-holes from the exterior. As my note-book has here fulfilled its part on the plans, I pass on to a description of the interior of this strong fortress.

The interior is divided into three stories, exclusive of the store room or dungeon, which is above the level of the ground, although entered from above, according to the usual practice, and exclusive also of the little closets in the upper parts of the turrets.

The first floor is a plain circular room, twenty-three feet in diameter[4], not even lighted by a loop-hole, and is approached immediately from the entrance by a straight passage (A), five paces long, and four or five feet broad, but without any thing like a vestibule, as drawn and described by King. In the centre is a large circular aperture, seven or eight feet in diameter, communicating with the dungeon below, at the bottom of which is said to be a well, now filled up ; others affirm that there is a subterraneous passage or sally-port from thence, an assertion unworthy of notice. Twenty-five steps[5], (giving a height of about thirteen feet and a half for the first room,) winding up the thickness of the wall, and lighted by a loop-hole at about the middle, conduct from the entrance passage to

The second foor. This room, on account of the recession of the interior wall, is about twenty-six feet in diameter, and is lighted by a large double window over the entrance (C), which has been before described. It is furnished with window seats, and ascended by some steps. The lintel is a massive square block, which is cracked from the giving of the arch. The upright dividing post or mullion, likewise quite plain, is only nine inches thick; at the sides are traces of the existence of strong bolts. On the opposite side of the room is a fine large fire-place (D) of handsome late Norman character, the upper part sloping to the wall, and projecting into the room, where it is supported by three clustered columns on each side, with stiffly foliaged capitals; the straight portion supported by these columns is deserving of attention, from the rise of a kind of a flat arch, the stones of which lock into one another in a peculiar manner. I find from the Glossary of Architecture, (where a very good view of this chimney-piece is given, pl. 54,) that a fire-place at Edlingham castle, of later date, and also those of the bishop of Soissons' palace, Septmons, are furnished with flat arches of this kind. The great west door of Rochester cathedral, and several segmental arches in Normandy are so built.

The only other light which is of any service to this room is a narrow loop-hole opposite the entrance door (B), and this, by the bye, occupies a dainty place, for it is immediately between the discharges of the two garderobes. The little attention of our forefathers, however, to these matters of delicacy, forces itself upon our notice in almost every ruin of their strong but comfortless abodes. At Cricceath and Beaumaris castles, in Wales, the garderobes are close to the grand entrances, and are the first things to greet both the eyes and noses of their chieftain's visitors. Such things and worse, however, do I understand, still exist in the city of Caen, in Normandy, at the present day, and fifty years ago they were, I am told, matters of course. The entrance to the lowermost of these garderobes is from this floor by the doorway (F), and thence by a flight of six steps. The further end is lighted by a loop-hole, and occupies part of the second right turret. Between the fire-place and the door by which we ascend, is a stoup or holy water basin (E) projecting from the wall.

Connected with the large window in this room, King in his Munimenta Antiqua gives us several very learned and in teresting pages of discussion, concerning the αἰθούα or guest chambers over the porch, and confers great honour upon Coningsburgh castle, by connecting it with the names of Homer and Menelaus and Ulysses. Unfortunately however, there is nothing but a window at Coningsburgh castle. The height of this room is given approximately by the number of steps which lead to the next floor, (thirty-four,) equivalent to about eighteen feet. The door of ascent (G) is between the fireplace and the large window, the stair is lighted by a loop-hole half way (H), and by another opposite the door at the top (I). The roof is crossed at intervals by massive square projecting ribs, between which the plaster coating still remains.The third floor is entered by a door over the window of the state room. It is larger in diameter than the chief apartment by about two feet and a half. A smaller double window, with steps and seats similar to the last described (K), affords it but a scanty light, which is not much increased by the narrow loop of the entrance, and what little finds its way out of the chapel. The large window is not so well preserved as the other, and cannot now be approached. This floor having little to fear from hostile attacks, the strength of the walls has been less regarded, three chambers being here formed within their thickness. The nearest of these to the entrance is the beautiful little chapel (L), which is formed in the thickness of the wall, and one of the turrets. It is a very interesting specimen of rather late Norman work, and finished with much care. Its form is a lengthened hexagon, with slender columns (some of which have been destroyed) at the angles to support the vaulting ribs, the effect of which rising from their foliaged capitals is very pleasing. A transverse arch, answering perhaps to the division of nave and chancel, and ornamented with a double chevron moulding, separates the vaulting into two compartments, each of which is crossed by diagonal ribs. These are ornamented in the outer division with a cable moulding of bold character, but if I interpret my note-book rightly, those to the east are different. The diagonal vaulting ribs appear to be stilted, but in this matter the eye cannot always be trusted. The line of the chapel bears S. S. E. 12 E. (magnetic), or about S. E. by E. 12 E., by the meridian, and at that extremity is lighted by a loop-hole, which answers for a chancel window. It occupies the face of the turret, is deeply splayed and ornamented on the inside by a cable and chevron moulding, supported by slender shafts with sculptured capitals. The chapel is further lighted, (perhaps from a later addition,) by two small quatrefoil lights (MM) in the two sides of the turret, the foliation is thin and on the outside; the interior part, which by reason of the splay is much the largest, being circular. Below these, but not exactly under them, is a trefoil-headed piscina (NN), with a very small nail-headed bead moulding running round it. I own myself rather doubtful as to its date, for although the bead moulding is apparently like Norman work, the trefoil head must be of later date. This elegant little specimen of early architecture reminded me of a very beautiful Norman chapel in Conway castle, only visible from a distance to those who have not a tolerable share of antiquarian enthusiasm[6].

On the left side as you enter the chapel is a square-headed door, leading from it into a small closet (O), which must I suppose have served for the priest's bed-room, the possession of which must have been an important ecclesiastical honour, at a time when a private bed-room was a luxury almost altogether unknown. It is lighted by a loop-hole, and has at the further extremity a square recessed locker (P), close against the stairs which ascend to the summit of the castle.

On entering the doorway of these stairs, a very narrow door on the left is observed, leading by a crooked passage (Q) to the upper of the two garderobes (R), which is in much the same state as when the castle was occupied, save that the wall above is broken away. It projects over the wall of the castle upon a large arch, which is thrown across the angle, formed by the contiguous turret, for the purpose of carrying it beyond the lower garderobe. On the opposite side of the room is a handsome fire-place (T), smaller than the one below, but decorated in a similar manner with clustered columns and foliaged capitals. The one is immediately over the other, and their flues pass straight up the wall, but do not unite, as will be mentioned presently. Close to the door of ascent to the roof is another stoup or holy water basin (S). The height of the room may be concluded from the number of steps leading to the summit, (twenty-four,) which will give about thirteen feet. These stairs pass through the wall in a contrary direction, and at the top are the remains of a door, by which we arrive upon the walls of the castle. A plan of their present appearance is here given, but it is not very easy to ascertain the nature of the roof, or the manner in which it was arranged. Around the interior circuit of the wall are large corbels, intended for the support of timbers. The turret (V), near which the ascending staircase terminates in a door (U), contains in its inner face a large circular arch. It has a level floor, close to which, on each side of the turret, is a very small square hole sloping to the exterior. The next turret contains an oven (W) in perfect condition, thus occupying a similar position to that in Orford castle, Suffolk, a notice of which may be seen in Mr. Hartshorne's admirable account of that ancient fortress, Archæologia, vol. xxix. p. 60. That which we are at present describing is two yards or more in its interior diameter, very well built and paved; the mouth is a small segmental arch, one foot three quarters high, and about the same in breadth. The two next turrets (XX) appear to have been in great part solid, with steps curving up on the inside, so as to make them serviceable as watch-towers. Near the turret opposite the door of ascent, and close to the inner circumference of the wall, are the flue vents from the fire-places[7]; they are very small and narrow, and separated at the top by a thin stone. At present there is no projection above the wall, and no trace of a chimney, properly so called, ever having existed. The summit of one of the watch-turrets, rather a giddy elevation, commands a fine and extensive view over the town on one side, and the vale of the Dun on the other. The two next turrets (Y and Z) are remarkable for the form and character of the chambers which they contain, if chambers they can be called from their small size. They have a low semicircular arch towards the interior, and their floor sinks two feet below the level of the top of the wall. The dotted line in the plan marks the semicircular arch. The angles cut off by dotted lines in the plan (**) are covered by stones level with the wall, so as to leave hollows beneath. The last turret only (Z) has a projection from the top, which looks like the ruins of a window, and which is seen in the distant view of the castle.

As peculiarities deserving attention at Coningsburgh, we may mention the flat lintels of the door and windows, generally characteristic of an early period, when the arch was rather a suspected wonder, than a principle well understood. These lintels generally occur in Saxon work, but are found also (like flat roofs to passages[8]) at a later period. The chimney flues are interesting examples, rather later I should suppose than those at Rochester. The absence of any light to the first floor is also a peculiarity, since we thus have two store rooms, or store room and dungeon, instead of one which is the usual practice. The large turrets and the oven have been mentioned as deserving of notice, and as resembling in both cases the arrangements of Orford castle. Connected with the occurrence of an oven at the summit of the castle, King mentions the existence of a kitchen on the top of some Welsh tower.

In the Glossary of Architecture the date of the fire-place is set down as circa 1170. From the general style of the chapel and fire-places, I should be inclined to consider this date sufficiently early, and perhaps place the erection of the castle rather nearer to the year 1200. A castle appears to have existed on the spot from a very early period. Caer Conan is given as the British name, translated by the Saxons Cyning or Coning Byrgh[9]. A castle at this place having jurisdiction over twenty-eight townships, afterwards belonged to King Harold, and on the overthrow of that prince William the Conqueror bestowed it with all its privileges on William de Warren, in whose family it remained till the reign of Edward III.[10] Some suppose that the present keep was built by William de Warren, but that date would be too early for the style of architecture.

Richmond castle, Yorkshire, occupies a very prominent position, being defended on three sides by a natural slope of considerable height and abruptness, while the third is connected with the more level ground on which the town is built. On this side is the lofty keep, which from its commanding situation is a striking object from every point of view. Two sides of the rocky promontory are washed by the river Swale, along whose banks are shady walks following the line of its rapid stream. The fortress appears to have consisted of a large irregular inclosure surrounded by high walls, which on three sides follow the natural boundary of the hill. The principal buildings now traceable are over against the keep above the river, and also towards the angle formed by the turn in the course of the stream. The keep forms part of the wall towards the town, and the entrance to the castle appears to have been between it and the river to the left, so as to be completely commanded. Along the wall to the left, as you enter from the town above the Swale, are a few traces of turrets and other small buildings, now appropriated as pigeon and rabbit-houses; but in the angle over the river before mentioned, is a large room commanding a delightful view over both reaches of the stream, the weir below, and the opposite woods and hills; a window placed here indicates the good taste of the builders. Nearer the keep, the chapel is recognised by a trefoliated piscina, and between this and the last-mentioned window is a horribly dark and gloomy square cavity, intended I presume for a dungeon; its depth to my surprise is stated at only about thirteen or fourteen feet. Opposite the keep along the line of the river is a large building, entered by a semicircular Norman arch. The ground floor, which is lower than the present surface, appears from the corbels which remain to have been vaulted; it was lighted by square-headed loop-holes. In the room above are double Norman windows towards the river-wall, with little central pillars. This building appears to be of about the same date as the keep. At the further angle of this river-wall is a watch-tower. There do not appear to have been any buildings along the curve from hence to the keep.

The keep, the chief object of interest, is of oblong form, and of great height. Its dimensions are stated at fifty-four feet by forty-eight on the exterior, with an elevation of ninety- nine or a hundred feet. As however the walls are about eleven feet thick, and the interior dimensions of the ground- floor are thirty-four feet by nineteen, a length and breadth of about fifty-six and forty-one would probably be nearer the truth. The walls batter slightly, and are well built; from the style of execution of the doors and windows I should suppose the tower to be about thirty years earlier than that of Coningsburgh. The breadth on the side next the main entrance is less than that on the opposite side, by reason of a recession in the plan at the angle, as shewn in the view of the keep, given in Whittaker's Richmondshire, and in the annexed ground-plans, but this is not the case at the level of the ground. The walls are flanked by flat Norman buttresses, which disengage themselves from the wall only at the level of the second floor. The square turrets, which rise from the angles at the summit, project as in most cases after the manner of flat buttresses below. The whole of the upper part of the tower, including the turrets and battlements, is, of course, to be referred to a later period, and for this reason I have given no plan of that part. The original entrance to the chief room of the keep was as usual on the first floor, by a semicircular-headed doorway of moderate size, falling back from the inner face of the tower, as above described. But it is rather remarkable at this castle, that not only is there a separate entrance to the dark apartments on the ground-floor, but this is by far the largest and most imposing of the two. It is a large semicircular archway between ten and eleven feet in breadth, ornamented both within and without with two massive nook shafts, having ornamented capitals.

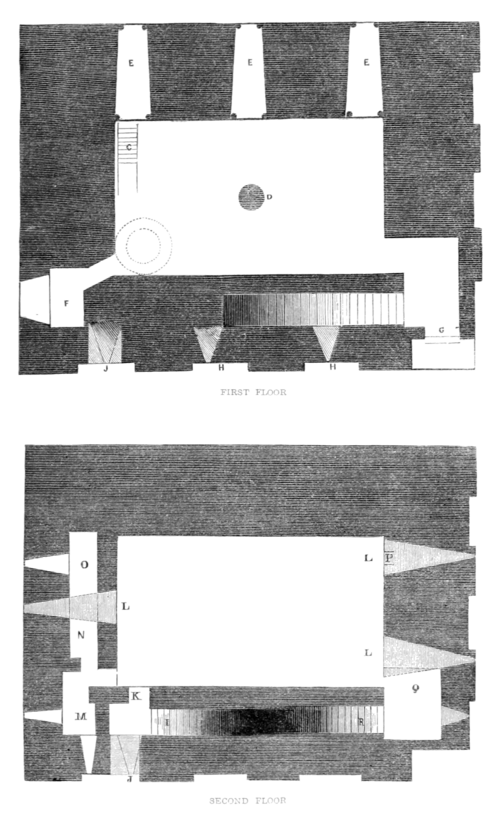

The ground-floor is without any light, except what now enters from the doorway lately opened, and from the destruction of a part of the vaulting adjacent. The interior measures thirty- four feet by nineteen, and the floor of the chamber above is supported by a very massive central pillar, square below, but passing into an octagon above. From this spring groining ribs, as indicated in the plan, the other extremities of which rest on octagonal shafts with square bases. The mouldings of these and the central pillar are remarkably analogous to those of the Perpendicular style. Hollowed out beneath the central pillar is a well (A), and in the face of the same towards the left side, is a hole near the top. At the entrance, the hole for the large wooden beam, or bolt, may be observed, as also traces of the iron hooks for the door-hinges. In the left hand corner, as we enter, is a projecting circular turret (B), entirely distinct from the main walls, and containing a winding staircase forming the present means of approach to the chief room on the first floor. The pavement of the room which we have just described is I understand the natural rock, it presents the appearance of large rough flags intersected by irregular cracks. Ascending the circular turret, which is lighted by a loop-hole looking towards the door, we arrive by the aid of a step ladder (C), (the turret being broken away at the top,) at The first floor. In the centre of this is a circular pillar (D) about three feet in diameter, broken away towards the top. The size of the apartment differs but little, if at all, from that which is below. Being the state room, it is lighted by three Norman windows (EEE) of moderate size, being four feet and a half in width on the inside. The splay is but slight, and at the sides, both on the interior and exterior, are shafts with fluted capitals. The inside arches are ornamented, and have a string-course embattled on the under side.In the thickness of the wall, at the same angle as the circular turret, is a small closet (F) with an unusually large window, seven feet broad; the width of the room is only four feet and a half.

At the other angle is a door four feet and a half wide, leading to the original entrance (G), which is broad, but not exhibiting any great precaution for strength. It is high above the ground, the accumulated rubbish in front having been lately cleared away, and with it the inclined plane, which, from traces then found, seems to have formed the means of approach by the intervention of a drawbridge, as at Rochester keep, and Pevensey castle. The view of the keep shews the former elevation of the ground previous to the late removal of the rubbish. The passage is nine feet wide, and at the door is a step to the platform in front, occasioned by the recession at this angle before mentioned. From the side of this entrance passage a straight flight of stairs (I), lighted by two loop-holes (HH), conducts to the second floor, which it enters by the door (K). Towards the top of the stair is a large doorway towards the exterior, at a great height from the ground (J); it has been blocked up in comparatively ancient times, and a perpendicular loop-hole inserted.

The second floor, entered by the door (K), passed along the top of the circular pillar, which aided in its support. This must have been rather a gloomy room, being lighted by only three loop-holes (LLL), which, though very wide on the inside, are but narrow slits on the exterior. Their height from the floor is very considerable. At P is a door leading to a closet, to which there is now no means of access; being in the thickness of the wall it is of course very small. A door near the entrance of the room, and to which you cross by means of a plank at rather a giddy elevation, leads to a small chamber (M) in the thickness of the wall, seven feet and a half long, and lighted by two loop-holes; adjoining it along the side wall of the castle is a long narrow passage (N); towards the further extremity is a loop-hole (O). The passage being low, passes beneath the loop-hole (L), which lights the central chamber in the same manner that the doorway (P) is beneath one of the opposite loop-holes. At (Q) is a lobby or vestibule conducting to the next staircase (R), and lighted by a loop-hole. The present means of approach to the foot of this stair is by a ladder from below. The staircase is lighted by four loop-holes, the uppermost of which slopes curiously through the wall; having reached the level of the third floor it turns the corner, and ascends by the side wall of the castle to the battlements and turrets. A very narrow door immediately round this corner, communicates with the

Third floor, which must have been remarkably gloomy, having only one (?) loop-hole at the further angle. In the ascent to the summit is another sloping loop-hole, and two others deeply splayed; there is also a loop from the interior, but whether to light the stair or the room is a matter of question. As there is nothing of any consequence to indicate in the plan of the third floor, I have not included it amongst the drawings which illustrate this description. The doorway leading from the staircase to the summit of the tower has a square lintel beneath a semicircular head[11]. As we now arrive at works of a much later era, exhibited in the battlements and turrets, we may conclude our antiquarian researches by a walk round the walls, whence the fine and extensive view of the town and scenery, which our lofty position commands, will amply repay the trouble of the ascent. A. MILWARD.

- ↑ For an interesting treatise on the Military Architecture of Normandy, see M. de Caumont's Histoire de l'Architecture au Moyen Age.

- ↑ See King's Munimenta Antiqua, vol. iii.

- ↑ In the following description, by first and second right or left turrets, I mean the turrets so situated to the right or left of the entrance.

- ↑ I did not measure it on account of the intervening mouth of the dungeon, others give 21 and 22 feet for the diameter.

- ↑ The width of the staircase I find stated at 5 feet.

- ↑ Its width is stated at 12 feet.

- ↑ In a short account of the castle published in the Gents. Mag. for 1802, part I., I find an allusion to the traces of some fixture under the lancet window of the chapel. I did not notice any thing of the kind, but presume there must have been a stone altar here originally. The quatrefoils are said to be 30 inches diameter on the interior, and 20 on the exterior. The chapel is stated also to be 10 feet by 12, and 15 or 16 feet high. Mention is made of an iron pipe to the piscina.

- ↑ See Edward the First's castles in Wales, Carnarvon, Conway, Beaumaris, and others.

- ↑ Coningsburgh is said to mean in Norwegian, "King's seat," Archæol. vi. 96.

- ↑ See Grose's Antiquities, Watson's History of the Warren family, vol. i. p. 30, and Camden's Britannia, by Gough, vol. iii. p. 268.

- ↑ I believe this to be the door to which my note alludes. I may here mention that I was not able to observe the arrangement of the buttresses on two sides of the keep, and have therefore omitted them.