Character of Renaissance Architecture/Chapter 5

CHAPTER V

CHURCH ARCHITECTURE OF THE ROMAN RENAISSANCE

As for the rest of the church of St. Peter, we need give attention to that part only which was designed by Michael Angelo on the basis of the original scheme of Bramante, namely, all to the eastward of,[1] and including, the first bay west of the crossing. The western bays of the nave as it now stands were, as is well known, added at a later time by the architect Maderna. The plan (Fig. 31) of the earlier part is thoroughly fine, and if the elevation had been made consistent with this plan, St. Peter's might have been one of the noblest monuments in Christendom. But the architects of the Renaissance rarely sought consistency in design; they were prone, from first to last, to mix incongruous elements. The essentially Byzantine plan here adopted could not be carried out in elevation with classic Roman details with a noble result; and the attempt which Michael Angelo made to produce an architectural effect foreign to the real structural system led of necessity, not only to such inconsistencies as are common in Renaissance motives, but to some awkward makeshifts which have not, I believe, been hitherto noticed by writers on this edifice.

Following what appears to have been Bramante's intention, Michael Angelo constructed barrel vaults over the arms of the cross,[2] supporting them on piers and arches which had been begun by Bramante. To this simple and reasonable scheme he applied a colossal order of Corinthian pilasters, a pair against each pier, as Alberti had done on a smaller scale at Mantua, and as Bramante appears to have intended in the great piers of the crossing, if not in all of the others. Apart from the superficial and purely ornamental character of the order, and its inappropriateness as ornament in such a system, its exaggerated scale dwarfs the effect of magnitude in the whole interior. The eye naturally estimates this magnitude by the customary proportions of a large classic order, and while these are by no means fixed, there is an approximate mean scale upon which we base our judgment. No beholder on entering St. Peter's can, indeed, fail to be impressed with the unusual size of the order; but he

Fig. 31.—Plan of St. Peter's, from Fontana.

is not apt to realize how far it exceeds the largest orders of antiquity. The order of the Parthenon is about forty-five feet high, and that of the portico of the Pantheon is about sixty feet. These are exceptionally large among the orders of Greek and Roman antiquity,[3] but the order of St. Peter's is one hundred feet high. The lack of due effect of scale in this interior has been often remarked, and it is generally attributed to the great magnitude of the structural parts. The size of these parts could not, however, well be different from what they are. Their magnitude is determined by the scale of the great dome and the width and altitude of the arms of the cross. The piers of the crossing are masses of masonry measuring on their longer sides more than fifty feet on the pavement, while the pendentive arches are one hundred and fifty feet high, and those of the arms of the cross are seventy-five feet high. But with appropriate treatment their scale might have been made more apparent. To adorn such piers and frame such arches with a classic order is to destroy the proper effect of scale, as well as to violate the true principles of architectural design by using structural members without any structural meaning.

Apart from the barbarism already remarked (p. 29) of springing a vault from a classic entablature, the effect of the gigantic order is unhappy in other respects; the great salience of its cornice cuts off from view the lower part of the vaulting, and this pronounced overhanging ledge, extending around the whole interior, breaks the continuity of the upright lines into the vaulting, and diminishes the effect of altitude.

But not only did Michael Angelo employ this incongruous and ineffective ornamental scheme for the interior of St. Peter's, he also adopted a corresponding design for the exterior which wholly contradicts the real character of the structure and led the architect into some curious makeshifts. For this exterior he used another gigantic order surmounted with an attic story. This obliged him to carry up the enclosing walls of the aisles to a height equal to that of the nave, and led to difficulties within. For the aisle vaulting was now far down below the top of these walls, and it therefore became necessary, unless the space above this vaulting was to be left open to the sky, with the enclosing wall standing as a mere screen answering to nothing behind it,[4] to construct a flat roof at the level of the attic cornice. Figure 32, a section through this part of the structure, will explain this and some other awkward expedients to which the architect was driven by the use of this colossal external order. Of the two compartments through which the line

Fig. 32. — Section of aisle of St. Peter's.

Such is St. Peter's church, which, though it has been much criticised, has been more generally lauded as a model of architectural greatness. Its real character has rarely been analyzed or rationally considered. That it has qualities of majesty and grandeur need not be denied; but these qualities are mainly due to its vast magnitude, and to what it retains of the design of its first, and greatest, architect. The manner in which the scheme of Bramante was modified and distorted by his successors, and chiefly by Michael Angelo, notwithstanding his professions of admiration for Bramante's intentions, is far from admirable, as I think the foregoing account of its structural and artistic aberrations must show. The building as a whole is characterized by incongruity and extravagance, and when we consider further that the ornamentation of the interior is for the most part a cheap deception, the rich coffering of the vaulting and the pilasters of the great order being wrought in stucco on a foundation of brickwork, we get the measure of the ideals and architectural standards of men who, like Vasari, could write of it that, "not in Christendom, nor in all the world, can a building of greater magnificence and grandeur be seen."[5] And this short-sighted admiration did not abate as time went on, as we learn from the estimates quoted by Fontana in his well-known book,[6] among which are the following: "Temple more famous than that of Solomon," "Unique miracle of the world," "Chief among the most celebrated of Christendom," "Compendium of the arts," "Basis of the Catholic faith," "Unique edifice of the orb of earth," etc., etc.

Before leaving St. Peter's a word may be said of a project for the building which was prepared by Antonio San Gallo the younger, Michael Angelo's immediate predecessor as architect for the fabric. This design, no part of which was ever carried out, is embodied in a wooden model preserved with that of Michael Angelo in the existing edifice. The most meritorious feature of this model is the dome which, from a structural point of view, is better than the one that was built, since it is well abutted both at the springing and at the haunch. This important condition is secured, however, by an architectural treatment that cannot be commended, and consists of two superimposed concentric arcades, the lower one surrounding the drum and abutting the vault at the springing, while the upper one is set in retreat and fortifies the haunch. The architectural effect of these arcades, which are of course adorned with classic orders, is not happy because an arcade with a classic order is not an appropriate form of abutment, though it may be made mechanically effective, and also because the upper circle, rising from within the circumference of the lower one, gives the composition an unpleasantly telescopic effect.

Our consideration of St. Peter's has led us to an advanced phase of the church architecture of the Roman Renaissance, and we must now go back and examine a few of the earlier structures in Rome and elsewhere that were produced under the distinctly Roman influence.

The church of Sant' Agostino is spoken of as a building of the early Roman Renaissance, and is said to have been built by the architect Giacomo da Pietra Santa between 1471 and 1484. But it is incredible that such a church could have been designed by any architect of the Renaissance, or by an Italian architect of any time. Letarouilly says of it that from the thirteenth century the Augustinians had a convent and small church in Rome, and that two centuries later they resolved to enlarge the church, and employed as architects Giacomo da Pietra Santa and a Florentine named Sebastiano.[7] The character of the building is such, however, as to warrant the belief that it is a mediæval structure with slight interior ornamental additions of the Renaissance, which may be by Pietra Santa, and a façade, dating from before the close of the fifteenth century, by Baccio Pintelli. In general character the church is in the style of the Rhenish Romanesque architecture of the twelfth century. It has a nave with groined vaulting in square compartments, each embracing two vault compartments of the aisles. It has also the Rhenish alternate system with plain square piers, and archivolts of square section, originally without mouldings, and the main piers have each a broad pilaster-strip carried up to the springing of the vaults. The triforium space has no openings, and the clerestory has plain round-arched windows. It is thus a thoroughly northern Romanesque scheme, entirely logical in its simple construction and fine in its proportions. The Renaissance interpolations consist of a few ornamental details only. A stilted composite column is set against the pilaster-strip of each main pier (Fig. 33), this column is crowned with an entablature-block reaching to the level of the triforium, and upon it is set a short pilaster surmounted with a smaller entablature-block at the vaulting impost. This superfluous and irrational compound, breaking the reasonable and effective continuity of the mediæval pilaster-strip, greatly disfigures the originally noble design. The only other neo-classic details of the interior are mouldings at the arch imposts and on the archivolts, and coffering on the soffits of the arches. These are quiet and less injurious in effect, though equally superfluous and inappropriate. Thus did the

Fig. 34.—Façade of Sant' Agostino.

sophistication of the Renaissance designers often blind them to real architectural excellence, and lead them to fancy that they could improve such an admirable and consistent interior by incongruous and meaningless features.

The façade (Fig. 34) is wholly of the Renaissance, and has no mediæval character except in its general outline, which conforms with that of the building itself. It is a simple design, and foreshadows those of Vignola and Della Porta for the church of the Gesù, to which it is superior in merit, being more reasonable and quiet. Shallow pilasters of considerable elegance mark the divisions of the interior, the portals are framed with simple classic mouldings without orders, and the aisle compartments are surmounted with reversed consoles after the manner of those introduced by Alberti in the façade of Santa Maria Novella in Florence. These consoles are, however, so different in character from the rest of the façade, having their details in higher relief and being set a little in retreat, that they would appear to be later interpolations. Answering to nothing in the building, they are superfluous ornaments, and do not improve the composition, which without them is as reasonable as a composition made up of superficial classic details can well be, A peculiar feature of this front is the truncated pediment that crowns the lower division, and forms the basis of the clerestory compartment. The small rectangular tablets that break the wall surfaces are also noticeable as foreshadowing a treatment that was subsequently much affected by Vignola. Contemporaneously with the façade, and by the same architect, a dome on a drum resting on pendentives was built over the crossing. The present dome rising directly from the pendentives is an alteration of a later time.

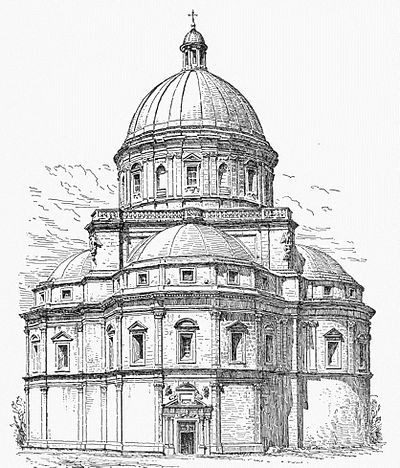

In the earlier churches that were wholly built under the Roman Renaissance influence, the Byzantine scheme largely prevails in the plan and structural forms, probably because it lent itself to the most effective display of a high central dome. Among the first of these buildings is the church of Santa Maria della Consolazione outside the wall at Todi. The design is attributed to Bramante,[8] and it seems to bear enough resemblance to what we know of his work to justify the attribution. The arms of the cross here take the form of apses, the eastern one being semicircular on plan, and the others polygonal. The dome (Fig. 35) is raised on a high drum, and is almost an exact reproduction of that of San Pietro in Montorio. Its thrusts are thus entirely unbuttressed, but it is probably bound with chains, as was the custom at this time in domes constructed in this manner.[9] The half-domes of the apses are better adjusted. They spring from within the supporting walls, which are carried up high enough to give effective abutment, and are loaded at the haunch by stepped rings of masonry, as in the Pantheon. The details of the interior (Fig. 36) consist of two superimposed orders of small pilasters, with great pilasters on the angles of

Fig. 35.—Exterior of Santa Maria della Consolazione, Todi.

the crossing reaching from the pavement to the springing of the pendentive arches, and from ressauts of the upper entablature converging ribs rise against the surfaces of the vaults. Several further awkward results are here noticeable as a consequence of this application of the inappropriate classic details to the Byzantine structural scheme. The entablature which is carried around the whole interior at the springing of the vaults, has to do duty at once for the small order of the upper stage

Fig. 36.—Interior of Todi.

and for the great angle pilasters, and thus in so far as it is in good proportion for the one it cannot be so for the other. Then the true magnitudes of the piers and the pendentive arches are falsified by the pilasters and simulated archivolts which spring from them. These piers and arches really embrace in width both the pilasters and archivolts and the spaces of wall and vaulting between them and the pilasters of the smaller orders and ribs which spring from them. The proper and impressive massiveness of the essentially Byzantine system employed is thus contradicted by an apparent skeleton of classic orders simulating an organic structural scheme which has no real existence.

Fig. 37. — Plan of San Biagio.

The exterior of this monument (Fig. 35) has much merit in its general form and proportions. The great central square mass, visible from the ground upward, gives the sense of support for the dome which the eye demands, and the apses with their half-domes are effectively grouped in subordination to the crowning feature. But this merit, which Todi shares with many other buildings of the Renaissance, is primarily due to the Byzantine scheme adopted, and cannot, therefore, be wholly credited to the Renaissance architect.

A variation of this scheme occurs in the church of San Biagio at Montepulciano by Antonio San Gallo the elder, and begun in the year 1518. Here the arms of the cross (Fig. 37) are square, with an apse added to the eastern arm. The interior is ornamented with a single, and very heavy, Doric order (Fig. 38), framing arched recesses in the imperial Roman manner.

Fig. 38.—Interior of San Biagio.

Fig. 40.—San Biagio, Montepulciano.

in order that the corner may be brought into line with the column, which gives more solidity to the angle. If the said angle were withdrawn into line with the middle pilasters, the façade, when viewed obliquely, with the round column on the angle, would appear imperfect, and for this … I strongly commend this form of angle because it may be fully seen from all sides."

Externally the composition is remarkably good in its larger features (Fig. 40). The dome, of slightly pointed outline, on a high drum, rises grandly from the substructure, and is well proportioned in relation to it. The wall surfaces are treated broadly, with no orders carried across them. They are divided into two stages, with a pediment over each façade. Superimposed pilasters are set on the angles, and a Doric entablature, carried across the whole front, with ressauts over the lower pilasters, divides the two stages. The wall of the lower stage is entirely plain, with a severely simple rectangular portal surmounted by a pediment. The wall of the upper stage is divided into rectangular panels, as in the attic of the Pazzi chapel in Florence, the central panel being pierced with a square-headed window and framed with an order of which the capitals are Ionic and the entablature Doric. The cornice of the top story and the raking cornice of the pediment of each façade are broken into ressauts over the pilasters, and an order of Ionic pilasters, with a very high entablature broken into ressauts, surrounds the drum which supports the dome. Square detached towers are set in the reentrant angles of the west side, only one of which was carried to completion. The completed one is in three stages, each adorned with a heavy order, Doric, Ionic, and Corinthian respectively. In these orders half-columns are coupled with angle pilasters, as in the interior, and the entablatures have ressauts on the angles over these members. An octagonal spire-like lantern, with a tall drum adorned with an order of Corinthian pilasters and surmounted by an attic, crowns the tower. Small obelisks set on the tower angles and reversed consoles against the angles of the attic give a simulation of Gothic form to the neo-classic scheme, and show the strong hold that mediæval ideas still retained upon the minds of the designers. The first of these spire-like towers of the Renaissance appears to be that of the church of Santo Spirito in Florence, which is spoken of by Milizia as the most beautiful of Italian bell towers.[11] It was designed by Baccio d' Agnolo, who, beginning as a wood carver, imbibed the new enthusiasm for the antique, and after studying the ancient monuments of Rome[12] began the practice of architecture. This campanile is thus noteworthy as the first of a large class of modern towers with spires of which Wren's famous steeples were the ultimate outcome. The scheme is based on the mediæval campanile, the earliest form of which is the Lombard Romanesque tower. The Lombard tower is characterized by its simple rectangular outline, the walls rising sheer from the ground to the cornice, and strengthened and adorned with shallow pilaster-strips, corbelled string-courses marking the successive stories, and by small grouped openings. The tower of Santa Maria Novella in Florence is designed on this model, and the neighbouring tower of Prato and Giotto's famous campanile are later and richer modifications of the same type. In the tower of Santo Spirito (Fig. 41) Baccio d' Agnolo has taken the Lombard scheme and clothed it with a pseudo-classic dress. While his classic details have much of that elegance which belongs to the best Italian work, they are out of place in such a structure. The tall pilaster-strips of the mediæval tower gave an expression as of an organic skeleton running through the building. They had been developed out of the classic pilaster to meet the needs of the mediæval type of structure, and in substituting the superimposed classic orders for the appropriate continuous members, the artist did violence to the true principles of design. The lantern with which this tower is crowned is an adaptation of Brunelleschi's lantern on the dome of the cathedral, but made more aspiring in form, so that the general outline is like that of a Gothic spire. But the form of a Gothic spire is far removed from anything that is proper to classic composition.Returning to San Biagio, it may be said that the orders here have a closer conformity with those of classic antiquity than occurs in the earlier monuments already mentioned, except the Tempietto of San Pietro in Montorio by Bramante.

In the nave of the church of Santissima Annunziatta in Arezzo, the same architect produced a different design. The nave (Fig. 42), of only three bays, is covered with a barrel vault, and the aisles have small domes on pendentives. The supporting piers are square with a shallow Corinthian pilaster on the face of each and an entablature passing over the crowns of the arches. The archivolts are deep, and each one is moulded on the face and plain on the soffit. These are carried on plain pilasters with simple impost mouldings. The wall above the entablature is plain and unbroken, except by a round-arched window over each bay of the ground story, and is crowned with a heavy cornice from which the vaulting springs. We have here a structural system of imperial Roman massiveness, necessitated by the use of the great barrel vault.

After the early part of the sixteenth century Italy produced few architects of a high order of genius. Most of the more advanced neo-classic art is the work of mediocre men who, while professing to be ardent advocates of grammatical correctness according to the ancient rules, were hardly less capricious in their misuse of classic elements than their predecessors had been. To enter upon the examination of any large number of buildings in this later Renaissance style would be tedious and unnecessary; but in addition to what we have already seen of it in the work of Michael Angelo in St. Peter's, we may give some attention to a few characteristic works of the two leading architects of the later time: Vignola and Palladio.

Few men did more to make the neo-classic ideas authoritative than Giacomo Barrozzi, called Vignola. Beginning like so many others with painting, Vignola was led early to the study of architecture, in which he strove to gain an exact knowledge of classic Roman forms by drawing and measuring the remains of the ancient edifices. He thus became a devoted partisan of the antique, and he wrote a treatise on the Five Orders which has been widely accepted as an authoritative guide in modern architectural practice. To him, says Milizia, "Architecture is under lasting obligations because he established it upon system, and prescribed its rules."[13] And the same author tells us further that Vignola "purified architecture from some abuses which neither his contemporaries nor the ancients had perceived"; yet nevertheless, he adds, "his book has produced more harm than good, for to make the rules more general, and more easy of application, he has altered the finest proportions of the antique." No system of architecture, Milizia says further, "is more easy than that of Vignola, but the facility of it is obtained at the expense of architecture itself." In his book,[14] which is made up largely of drawings and diagrams, Vignola shows how the proportions of an order may be regulated by a module down to the smallest details. He explains how to construct Ionic volutes and other curves from centres, and how to describe the details of Corinthian and composite capitals by means of plan and elevation. He thus introduces a mechanical system modelled after the formulas of Vitruvius.

But notwithstanding his ardent advocacy of the principles of ancient Roman art, Vignola, in his own practice, not only altered the proportions of the orders as Milizia says, but made many fanciful changes in them. He introduced details which have no counterparts in correct Roman design, and freely mixed those of different orders. An instance of this occurs in an

Fig. 43.—Vignola's entablature.

entablature figured in his book,[15] which he calls his own invention. In this composition (Fig. 43) we have a pseudo-Doric frieze between an architrave with multiplied faciæ, and a cornice on modillions. In the place of triglyphs this frieze has consoles with two channels, like those of a triglyph, on the curved face of each. To such travesties of classic design did the striving after novelty, which was curiously mingled with their ardour for the antique, lead the men of the later Renaissance. For an advocate of classic correctness such aberrations are the more surprising as they are expressly condemned by Vitruvius, who warns his readers against them as follows: "If dentiled cornices are used in the Doric order, triglyphs applied above the voluted Ionic, thus transferring parts to one order which properly belong to another, the eye will be offended, because custom otherwise applies these peculiarities."[16] The Roman writer might, indeed, have given a better reason why the purity of the orders ought to be maintained, namely, because to each of them the fine artistic genius of the Greeks had given its appropriate details.

Fig. 44.—Half plan of Sant' Andrea.

In designing entire buildings Vignola shows no less freedom in unclassic and incongruous combinations. This is manifested in the earliest of his church edifices, that of Sant' Andrea di Ponte Molle outside of the Porta del Popolo at Rome (Figs. 44, 45, and 46). It is a small, oblong, rectangular enclosure covered with a dome of oval plan on pendentives. The structural scheme is thus primarily Byzantine, but the architectural treatment is Roman. The dome is built in a praiseworthy form, and follows the construction of the dome of the Pantheon. An enclosing drum is carried up from the pendentives to a considerable height, and the haunch of the vault is well fortified by stepped rings of masonry. These rings are criticised by Milizia[17] as awkward and unnecessary because, he affirms, the vault might have been made secure without them. He probably means that it might have been bound with chains in the usual manner of the Renaissance. As in the Pantheon, the drum rises so high above the springing that but little of the dome is visible externally. The character of the rectangular substructure is puzzling to the eye of a beholder who looks for meaning and congruity in architectural forms. Wrought in shallow relief upon its façade is an order of Corinthian pilasters surmounted by a classic pediment, and the entablature of the order is returned on the sides of the building. The effect of the whole may be compared to that of a Greek temple with an attic supporting a dome built upon it. So awkward is the combination that it might be supposed to be a piece of patchwork in which a building of Greek temple form had been altered to gain more height within, were it not that

Fig. 45.—Longitudinal section of Sant' Andrea, from Vignola's book.

we find in the architect's own book the plan and section reproduced in Figs. 44 and 45, which show that the building as it now exists was originally designed in its present form.[18]

On reflection we discover that the scheme suggests a derivation from the Pantheon. Not only is the dome shaped and adjusted as in that ancient monument, save for its oval plan, but the rest of the composition is pretty clearly from the same source. To realize this it is necessary only to eliminate, in idea, the portico of the Pantheon with the exception of its pediment, and to conceive this pediment as drawn back into the plane of the rectangular façade. The pediment would then surmount the order of Corinthian pilasters which adorn this façade, and the

Fig. 46.—Sant' Andrea di Ponte Molle.

resulting composition would be substantially identical with that of the façade of St. Andrea. The minor differences are unimportant, as where Vignola has placed a pair of pilasters, instead of only one, at each end of the façade, has given the whole order more shallow relief, and has omitted the fluting on the pilasters. Even the niches on either side of the portal are reproduced from the Pantheon, though Vignola has pierced them with windows.

The likeness extends farther. The return of the entablature along the side walls and the cornice of the attic are the same in both instances; but the second pediment in the Pantheon façade Vignola has not reproduced. St. Andrea is thus a close, though a modified, copy of the rectangular part of the Pantheon, with the rectangle elongated and surmounted by a dome designed on the Pantheon model. It was not known in the sixteenth century that the ancient monument is not a homogeneous structure, but an awkward patchwork, the result of successive alterations and additions.[19] Vignola took it entire as an example of that ancient style which he regarded as authoritative, and based his design for St. Andrea upon it, just as many modern architects have taken motives from Vignola himself. If it were proposed to erect a dome upon the Parthenon, few people would fail to see that the result would be an architectural monstrosity, yet this would not be very different from what was done in St. Andrea by an architect who has been looked upon as a champion of classic correctness in design.

M. Palustre has called attention to the fact that, in the interior of St. Andrea (Fig. 45), the two parts of the entablature which have no raison d'être under a vault have been omitted.[20] But the impropriety of a complete entablature in connection with vaulting is no greater than that of any part of a classic order, which has no justification in such connection, as we have already remarked.

The pilgrimage church of Santa Maria degli Angeli, built over the oratory of St. Francis at Assisi, is a more extensive monument which was begun by Vignola in the year 1569. Though completed by other architects, and extensively restored in 1832, the building as it now stands is uniform in style throughout, and bears the marks of Vignola's manner of design. It is cruciform in plan, with a long nave and aisles, and a square chapel opening out of each bay of each aisle. The nave and transept have barrel vaulting, a half-dome covers the apse, and a dome on a high drum resting on pendentives rises over the crossing. The aisles have domical groined vaulting with transverse ribs, and the side chapels have barrel vaults with their axes perpendicular to that of the nave. These chapels thus form abutments to the inner vaulting, so that no external buttresses are needed. The entire fabric is of brick, but the details, including the orders of the interior, of the west front, and of the drum, are wrought in stucco. For the interior the architect has employed a great order of Doric pilasters, a single pilaster on the face of each pier, and on the sides of the piers, under the aisle archivolts, he has placed pairs of smaller pilasters. The soffits of the archivolts are very wide, and have each a pair of salient sub-archivolts corresponding with the pilasters. It had been common for the architects of the Roman Renaissance to break the entablature into ressauts over the columns or pilasters of the orders when used in this way, as San Gallo had done in Montepulciano and Michael Angelo in St. Peter's. But the effect of thus breaking the continuity of the cornice line is unpleasing, and Vignola has avoided it here by confining the ressaut to the architrave, frieze, and bed-mouldings, leaving the corona of the cornice unbroken as in Figure 47. The great piers of the crossing show the influence of St. Peter's in being splayed, and the forms of the pendentives lose their spherical surfaces in being fitted to the straight line of the splay, as they do in St. Peter's. The design of the façade expresses with unusual truthfulness the divisions of the interior, which are marked by pilasters like those of the great order within, and by an arch coinciding with the curve of the vaulting.The Gesù in Rome, another large church by Vignola, and built at about the same time as Santa Maria degli Angeli, is a

Fig. 48.—Plan of the Gesù.

variation of the same scheme, and shows in a more marked degree the influence of St. Peter's. A plan of this building, the intended façade which Vignola did not live to construct, and the existing façade by Jacomo della Porta are given in the addendum to the edition of the architect's book on the Five Orders published in 1617 already referred to (p. 84), and are reproduced in Figures 48, 49, and 50. The aisles are omitted here so that the side chapels, which communicate with each other by narrow openings in the dividing walls, open directly out of the nave. The transept is short, and extends on either side beyond the nave only by the thickness of its walls. An elevated dome on pendentives, circular on plan within and octagonal on the outside, rises over the crossing, and barrel vaults cover the nave and transept arms. The side chapels are vaulted, with small domes on pendentives, except those in the angles of the crossing, which do not require pendentives because their supports are shaped to the circular form as shown in the plan. Figure 48. These supports are made heavier than the others in order to strengthen the crossing piers, which, in consequence of this reenforcement, do not need to advance so far into the space under the great dome as they otherwise would. In Santa Maria degli Angeli the aisles prevent this treatment, and the crossing piers extend far into the nave and narrow the spans of the crossing arches.

The scheme of the interior of the Gesù is a close reproduction of that of St. Peter's, though the great pilasters are of the composite, instead of the Corinthian, order, and other minor differences are noticeable. It is worthy of remark that the entablature has no ressauts except at the crossing, and the vaulting is raised upon an attic, so that no part of it is hidden from view by the cornice of the entablature, as it is in St. Peter's. It is also noticeable that, while capricious in the use of elements derived from the antique, Vignola in his church architecture eliminates mediæval forms more completely than most architects of his time. Where in St. Peter's, for instance, the apses have celled vaults on converging ribs, he employs the plain half-dome of Roman antiquity.

Vignola's design for the façade (Fig. 49) presents the familiar features of his style as already embodied in the earlier façade of St. Andrea, but with additional infractions of propriety, as well as of classic form in its more elaborate details. This façade corresponds in outline with the form of the building, except for the podium of the upper story (which contradicts the roof lines of the side chapels), and the abutting walls of curved outline over the side compartments. The chief aberrations of detail are the broken pediments of the doors and windows, and

Fig. 49.—Façade of the Gesù, Vignola.

the barbaric scrollwork and hermæ, the use of which this architect did much to establish. How far the barbarism of breaking the pediment was an independent freak of the Renaissance I do not know. Instances of somewhat similar treatment occur in the Roman architecture of Syria, as in Baalbek (Fig. 51),

Fig. 50.—Façade of the Gesù, Della Porta.

The actual façade by Della Porta (Fig. 50) follows the main lines of Vignola's design, but the details are much altered. The podium of the upper story is raised in height, reversed consoles are substituted for the plain curved abutments of Vignola, and the raking cornices of the small pediments are made whole. But other aberrations take the place of those which are eliminated, as that of placing one pediment within another over the central portal, and the ugly shapes and framings of the tablets and niches that break the wall surfaces. Della Porta had acquired these habits of design from his master, Vignola, and how far Vignola himself could go in such monstrosities is shown in some of the figures of his book already spoken of. Figure 52 from this book affords an instance.

If Vignola did much to make authoritative the later ideas of the sixteenth century as to the principles of ancient art and their application to modern uses, Palladio did even more. By the example of his numerous architectural works, as well as by his writings, the influence on modern art of this famous neo-classicist has been greater than that of any other architect of the Renaissance, so that we have, in the principal countries of Europe, a style of architecture which is known as Palladian. Palladio was the first architect of the Renaissance who was not at any time either a painter or a sculptor. He begins his well-known book[21] as follows: "Guided by natural inclination, I began in my earliest years to devote myself to the study of

Fig. 52.—Tablet from Vignola.

architecture, and having been always of the opinion that the ancient Romans were in building, as in many other things, far in advance of all those who came after them, I took for my master and guide Vitruvius, who is the only ancient writer on this art, and I set myself to the investigation of the remains of the ancient edifices which, injured by time and the violence of barbarians, are still extant. And finding them much more worthy of attention than I at first thought, I began with great diligence to measure most minutely every part of them. I became so ardent an investigator, not having known with what judgment and fine proportion they had been wrought, that not once only, but many times, I visited different parts of Italy and elsewhere, in order to understand and delineate them completely. And seeing how far the common manner of building differs from what I have observed in the ancient edifices, and read in Vitruvius, and in Leon Batista Alberti, and in other excellent writers since Vitruvius, and from that new manner which I have practised with much satisfaction, and which has been praised by those who profited by my work, it has seemed to me right, since man is not born for himself alone, but also to be useful to others, to publish the drawings of these edifices, which at the cost of much time and peril I have gathered; and to state briefly that which has seemed to me most worthy of consideration in them, together with those rules which I have observed, to the end that those who shall read my book may profit by such good as may be in it, and supply that which may be wanting (for much, perhaps, may be) so that, little by little, we may correct the strange abuses, the barbarous inventions, avoid the superfluous cost, and (what is more important) the various and continued deterioration which we see in so many buildings."

The implicit confidence of the neo-classicists in the art of Roman antiquity as the embodiment of all true principles of architectural design, and their unquestioning belief that mediæval art was wholly false in principle and barbaric in character, have seldom been more naïvely expressed.

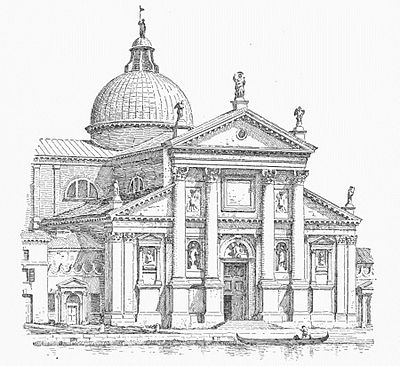

Of church architecture by Palladio we have two important buildings, San Giorgio Maggiore and the Redentore, both in Venice. The first of these stands on the island of San Giorgio, opposite the Piazzetta, and is a characteristic Palladian design, though some parts of the west front may have been added after the architect's death. This church is cruciform, and has barrel vaulting with interpenetrations for light, and a dome on pendentives over the crossing. The piers are heavy, with a single engaged column of the composite order, raised on a high pedestal, against each one, except at the crossing, where the columns are coupled with pilasters, while the wide archivolts rest on pairs of smaller pilasters of the Corinthian order, without pedestals (Fig. 53). Both columns and pilasters have strong entasis, and the frieze of the entablature is rounded in profile. In raising the great order on pedestals Palladio conformed more closely to ancient Roman practice than Michael Angelo and Vignola had done; but the pedestals have a clumsy effect thus ranged along the nave, and their sharp angles are in the way of moving crowds of people. It is noticeable, too, that Palladio has introduced complete orders under the archivolts, giving an entablature to each pair of small pilasters. The entablature had before been omitted in this situation. The whole scheme shows in a marked degree how inappropriate is the use of classic orders in a church interior. The application of such orders to a building with aisles and a high nave obliges the designer to make awkward combinations, and to violate true classic usage in manifold ways, as we have already abundantly seen. He must associate large and small orders, and give them relationships and adjustments that belong to mediæval, rather than to classic, composition. The façade of this building (Fig. 54) has the merit of conforming in outline to the shape of the nave and aisles. It is the outline of the primitive Christian Roman

Fig. 54.—Façade of San Giorgio.

basilica without any disguises in the way of reversed consoles over the aisle compartments, or divisions contradicting those of the interior. Instead of the superimposed orders of Vignola's west fronts, Palladio has here, in the nave compartment, one great order of engaged columns, on high pedestals, rising through the entablature of a small order of pilasters, which is carried across the whole front, reaching to the height of the aisles. The total scheme gives a suggestion of mediæval organic position, but has no real organic character pertaining to the building.

In the façade of San Francesco della Vigna, also in Venice, and by the same architect, the design of San Giorgio is repeated, with some notable changes in detail. In this case the small order, as well as the larger one, consists of columns, except that on each angle a pilaster takes the place of a column, and both orders rise from the same level, the smaller one resting on a continuous podium, and the larger one on pedestals which are ressauts of the podium. The entablature of the small order is

Fig. 55—The Redentore, Venice.

here not continuous, but is broken by the nave compartment, though a fragment of it is inserted in the central bay of this compartment over the small columns that flank the portal.

The scheme of the Redentore differs from that of San Giorgio. It has no transept and no aisles, but in the place of aisles a series of side chapels. A square area in front of the sanctuary is covered with a dome on pendentives, while the nave has a barrel vault, and the side chapels have barrel vaults with their axes perpendicular to the axis of the nave. From the dividing walls of these chapels solid abutments in pairs are carried up through the lean-to roofs over the chapels to meet the thrusts of the nave vaulting, as shown in the general view of the exterior (Fig. 55). The plan of the east end is peculiar. A round apse opens out of the north and south sides of the square covered by the dome, and a colonnade on a curved plan forming the sanctuary bounds this square area on the east side. Beyond this is an oblong enclosure the eastern wall of which is on a curved plan, and the sanctuary is flanked by small towers. The interior has a great order of Corinthian columns, one against each pier, resting directly on the pavement, and the small pilasters under the archivolts carry entablatures which extend to the outer wall and from them the barrel vaults of the chapels spring. The entablature of the great order is not set in the wall and broken by ressauts to cover the columns, as in San Giorgio; but is carried by the columns, and thus overhangs the wall with a supporting corbel in the middle of each intercolumniation which forms a keystone to the arch beneath. The façade of the Redentore is a variation of that of San Giorgio with the pedestals omitted from the great order, as in the interior, and it has an attic behind the pediment like that of Vignola's small church of St. Andrea at Rome. Such is the nature of Palladian church architecture. We shall see more of Palladio's art when we come to the consideration of the later civil and domestic architecture of the Renaissance.

It is unnecessary to multiply examples of the church architecture of the Roman Renaissance, i.e. that architecture which derived its character primarily from the influences that were active in Rome from the beginning of the sixteenth century. For while the churches of this style differ considerably one from another in details, they agree essentially in architectural treatment growing out of a closer contact with ancient monuments, though with no strict conformity to them. Descriptions of minor differences in the forms of such buildings, and in the composition of their ornamental details, are tedious, and enough of them have now been given. We may, therefore, in the next chapter, pass on to the consideration of the palace architecture of the Renaissance.

- ↑ I call the end of the sanctuary "the east end" according to the nomenclature of the usual orientation. St. Peter's, as is well known, does not conform to the general rule which has prevailed since the fifth century.

- ↑ These vaults may have been begun by some of his predecessors. It is impossible to make out how far the building had been actually advanced by them,

- ↑ The colossal order of the Temple of the Sun at Baalbek is so unique in scale, and so little known, that it does not influence our general notions of the size of a large classic order.

- ↑ As it actually does in the western part of the nave built by Maderna.

- ↑ Le Vite, etc., vol. 7, p. 249.

- ↑ Il Tempio Vaticano e sua Origine, etc. Discritto dal Cav. Carlo Fontana, Rome, 1694, vol, 2, p. 406.

- ↑ Letarouilly, Edifices de Rome Moderne, Paris, 1860, p. 350.

- ↑ Milizia, op. cit., vol. i, p. 144, affirms that it is by Bramante.

- ↑ Cf. Fontana, op. cit., vol. 2, p. 363.

- ↑ Bk. 3, p. 54.

- ↑ Op. cit., vol. 2, p. 240.

- ↑ Op. cit., vol. 2, p. 239.

- ↑ Memorie, etc., vol. 2, p. 36.

- ↑ I Cinque Ordine d’Architettura.

- ↑ Op. cit., plate 32.

- ↑ Bk. I, chap. I.

- ↑ Op. cit., vol. 2, p. 30.

- ↑ The drawings are found in the addendum to the edition of 1617, plates 7 and 8.

- ↑ Recent investigations, the results of which are set forth by Signor Beltrami (Il Pantheon, Luca Beltrami, Milan, 1898), have shown that the existing portico is of later date than either the rotunda or the rectangular front against which it is set.

- ↑ "A l'interieur, pourtourné de pilastres également Corinthiens, deux parties de l'entablement qui n'ont pas leur raison d'être sous une voute, c'est-a-dire la frise et la corniche, par un raffinement peu habituel aux Italiens, ont été supprimées." L'Architecture de la Renaissance, par Leon Palustre, Paris, Quantin, p. 72.

- ↑ Quatro libri dell’ Architectura di Andrea Palladio, Venice, 1581.