CHAPTER II.

ADDLER'S HALL.

The whole court

Went boiling, bubbling up from all the doors

And windows, with a hideous wail of laughs

And roar of oaths, and blows, perhaps .... I passed

Too quickly for distinguishing, .... and pushed

A little side door hanging on a hinge,

And plunged into the dark.—Elizabeth Barrett Browning.

n the western side of Scotland Road—that is to say, between it and the Docks—there is a regular network of streets, inhabited mostly by the lowest class of the Liverpool poor. And those who have occasion to penetrate their dark and filthy recesses are generally thankful when they find themselves safe out again. In the winter those streets and courts are kept comparatively clean by the heavy rains; but in the summer the air fairly reeks with the stench of decayed fish, rotting vegetables, and every other

conceivable kind of filth.

n the western side of Scotland Road—that is to say, between it and the Docks—there is a regular network of streets, inhabited mostly by the lowest class of the Liverpool poor. And those who have occasion to penetrate their dark and filthy recesses are generally thankful when they find themselves safe out again. In the winter those streets and courts are kept comparatively clean by the heavy rains; but in the summer the air fairly reeks with the stench of decayed fish, rotting vegetables, and every other

conceivable kind of filth.

The children, that seem literally to swarm in this neighbourhood, are nearly all of a pale, sallow complexion, and of stunted growth. Shoes and stockings and underclothing are luxuries they never know, and one good meal a day is almost more than they dare hope for. Cuffs and kicks they reckon upon every day of their lives; and in this they are rarely disappointed, and a lad who by dodging or cunning can escape this daily discipline is looked upon by the others as "'mazin' cute."

To occupy two rooms is a luxury that only comparatively few families indulge in. Why should they pay rent for two rooms when one will answer the purpose? "We know a trick worth two o' that," is their boast. And so year by year they bid defiance to all law and authority.

The police rarely, if ever, venture into this neighbourhood alone, or if one should be foolish enough to do so, he has generally to pay dearly for his indiscretion. House agents and policemen are objects of special aversion.

A friend of ours, some years ago, came into considerable property in the neighbourhood, and employed a young man who was new to the work to collect the rents for him. On entering the first house the agent was confronted by a big, villanous-looking man, who demanded in a surly tone what he wanted.

"I am come for the rent," said the agent.

"Oh, you have, have you?" was the reply.

"Yes."

"Ah! Did anybody see you come in?"

"No."

And instantly seizing a huge poker and waving it in the air, he shouted to the affrighted agent, with a terrible oath, "Then I'll take care nobody ever sees you go out."

This had the desired effect, and the terrified agent escaped for his life. At the next house at which he called he was received very blandly.

"So you have come for the rint, have you?"

"Yes, that is my business."

"Ah, yes, indeed, very proper. Could you change a five pun' note, now?"

"Oh, yes."

"That will do." Then raising his voice to a loud pitch, he shouted, "Mike, come down here ; there's a chap that 'as five pun' in his pocket; let's collar him—quick!"

And a second time the affrighted agent fled, and gave up the situation at once, vowing he would never enter any of those streets again while he lived.

It was to this neighbourhood that Benny Bates and his sister wended their way, after leaving old Joe and his warm fire. Whether the lamplighter had neglected his duty, or whether some of the inhabitants, "loving darkness rather than light," had shut off the gas, is not certain; but anyhow Bowker's Row and several of the adjacent courts were in total darkness.

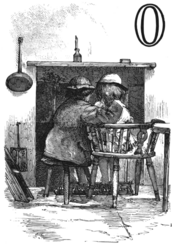

This, however, seemed no matter of surprise to Benny and little Nell, who wended their way without difficulty along the rough, ill-paved street. At length they turned up a narrow court, darker and dirtier even than Bowker's Row, which went by the name of "Addler's Hall." About half-way up this court they paused for a moment and listened; then, cautiously pushing open a door, they entered the only home they had ever known.

They paused for a moment and listened.

Much to their relief, they found the house empty. A lump of coal was smouldering in the grate, which Benny at once broke up, and soon a ruddy glare from the fire lighted up the dismal room.

The furniture consisted of a three-legged round table, a chair minus a leg, and a three-legged stool. On the window-sill there was a glass bottle with a candle stuck in the neck, and under the stairs there was a heap of rags and shavings, on which Benny and his sister slept. A frying-pan was suspended against the wall near the fireplace, and several cracked cups and saucers, together with a quart mug, stood on the table. The only other article of furniture was a small cupboard in a corner of the room close up to the ceiling, placed there, no doubt, to be out of the way of the children.

Drawing the chair and the stool close up to the fire, Benny and his sister waited the return of their parents.

Outside, the wind moaned and wailed, and whistled through the keyhole and the chinks in the door, and rattled the paper and rags with which the holes in the window were stopped. And as the children listened they shivered, and drew closer together, and nearer the fire.

"By golly!" said Benny, "this house is like a hair-balloon. I wish as how we could keep the wind out.

"You can't do that, Benny; it creeps in everywheres,"

"Are 'e cold, Nell?"

"No, not very; but I's very hungry."

Just then an uncertain step was heard in the court outside, and the next moment their stepmother staggered into the room.

"Now, out of the way, you brats," was her greeting, "while I cooks your father's supper."

And without a word they got out of her way as quickly as possible, for they saw at a glance she was not in the best of humours. They were pleased to see, However, that she had brought with her a loaf of bread, some butter, and several herrings, and so they were hopeful that for once they would get a good supper.

"Now, out of the way, you brats," was her greeting.

The supper was not quite ready when their father came in, flushed and excited.

"Where's the brats?" was his first angry exclamation, glancing round the room.

"There," said his wife, pointing under the stairs, where the children were crouched.

"Come out here, you young vermin; quick! do you hear?"

And the frightened children came out and stood before him.

The frightened children came out and stood before him.

"Have you brought me that sixpence that I told yer? For, if you ain't," said he, scowling at Benny, "I'll loosen yer hide for yer in double-quick time."

"Ay," said the little fellow, producing the sixpence, "'ere it are."

"Is that all you've got?"

Benny shot a quick glance at his sister before replying, which, however, did not escape his father's eye.

"Ay" he said, stoutly; "I ain't got no more."

"You lie, you villain!" roared the father; "fork it out this moment."

"I tell yer I ain't got none," said Benny. Nelly was about to speak here, but a glance from her brother silenced her.

"Will you fork it out?" said the father again.

"No," was the reply.

In a moment Dick Bates had taken the leather strap from his waist, and without mercy rained blow after blow upon the head and shoulders of his child.

At first Benny bore the blows without shrinking and without uttering a cry; but this only the more aggravated the inhuman father, and faster and more furious fell the blows, till the little fellow shrieked with pain and begged for mercy. But there was no mercy in the father's heart, and still the blows fell, till little Nelly, unable longer to bear it, rushed in between her father and brother, saying, "You shall not beat Benny so."

"Oh, you want it too, do you?" roared he. "Then take that, and that, and that."

"Father," said Benny, "will you strike Nell?"

The question for a moment seemed to stagger him, and he looked down upon the pleading face of his suffering child, and into those great round eyes that were full of pain and tears, and the hand that was raised to strike fell powerless to his side, and with a groan he turned away.

What was there in the face of his little daughter that touched this cruel, besotted man? We cannot tell. Perhaps he caught a glimpse in that sweet face of his early love.

It is said that he loved his first wife dearly, and that while she lived he was tolerably steady, and was never unkind to her. He even went with her to the house of prayer, and listened to her while she read the Bible aloud during winter evenings. These were happy days, but when she died all this was changed; he tried to forget his trouble in drink, and in the companionship of the lowest and most degraded men and women.

Then he married again, a coarse drunken woman, who had ever since led him a wretched life; and every year he had become more drunken and vicious.

If he yet loved anything in the world, it was his "little Nell," as he always called her. She was wonderfully like her mother, the neighbours said, and that was doubtless the reason why Dick Bates continued to love her when all love for everything else had died out of his heart.

He had never treated her before as he had treated her to-night; it was a new experience to the child, and for long after she lay on her heap of shavings with dry eyes and hot cheeks, staring into vacancy.

But when the last spark of fire had died out, and her father and stepmother were asleep in the room above, turning to her brother, who was still awake, she said, "Put your arm about me, Benny, will yer?"

And Benny put his arm around his little sister, and pressed her face to his bosom. And then the fountain of the child's tears was broken up, and she wept as though her heart would break. Great sobs shook her little frame, and broke the silence of the dreary night.

Benny silently kissed away the tears, and tried to comfort the little breaking heart. After awhile she grew calm, and Benny grew resolute.

Benny put his arm around his little sister.

"I's not going to stand this no longer," he said.

"What will you do, Benny?" she asked.

"Do? Well, I dunno, yet; "but I's bound to do some'at, an' I will too."

After awhile he spoke again. "I say, Nell, ain't yer hungry? for I is. I believe I could eat a gravestun."

"I was hungry afore faather beat me, but I doesna feel it now," was the reply.

"Well, I seen where mother put the bread an' butter, and if I dunna fork the lot, I's not Ben Bates."

"Bat how will yer get to it, Benny?"

"Aisy 'nough, on'y you most 'elp me."

Benny was able to reach the cupboard without difficulty.

So without much noise they moved the table into the corner of the room underneath the cupboard, and placing the chair on the top of the table, Benny mounted the top, and was able to reach the cupboard without difficulty.

A fair share of the loaf remained, and "heaps of butter," Benny said.

"Now, Nell," said he, "we'll 'ave a feast."

And a feast they did have, according to Benny's thinking, for very little of either loaf or butter remained when they had finished their repast.

"What will mother say when she finds out?" said Nelly, when they had again lain down.

"We must be off afore she wakes, Nell, and never come back no more."

"Dost 'a mean it, Benny?"

"Ay do I. We mun take all our traps wi' us i' t' morning."

"Where shall us go?"

"Never fear, we'll find a shop somewheres, an' anywheres is beter nor this."

"Ay, that's so."

"Now, Nell, we mun sleep a bit, 'cause as how we'll 'ave to be stirring airly."

And soon the brother and sister were fast asleep, locked in each other's arms.