History of the 305th Field Artillery/Brest, Pontanezin, and the Chemin de Fer

VIII

BREST, PONTANEZIN, AND THE CHEMIN DE FER

Down in the throat of the harbor the houses of Brest detached themselves from the hillside. Small boats bore I'rench oficials and men in our own uniform to us.

The Von Steuben anchored in the inner harbor. The Northern Pacific was warped against a stone pier. A few soldiers waved their hands at us. Here and there a French civilian stared, saluted, and passed on. We had come when the world waited in suspense between two phases of the great German offensive. It did not seem odd that we were welcomed as we had greeted France, with sensations that unconsciously avoided expression.

Colonel Doyle had caused so much to be read to the regiment, under orders from G. H. Q., of precautions of one sort and another that many men expected to be invited ashore at once and introduced to all the gaieties of the city. Now it was announced that, except for the baggage details, no one would be allowed ashore. Glancing back, the prisoners seem to have had something the better of it.

The details, with packs, left the ship at dusk and marched through the railroad yards to an unpainted enclosure, crowded with long, low sheds. Our baggage would be brought from the ships in scows to the enclosure. We would sort it there and carry it to the sheds reserved for the 305th. We were told what to expect.

"No man will be permitted to leave the yard. There's nothing to do until the lighters begin dumping the baggage. Make yourselves comfortable."

A friendly fellow who had been through the mill gave us a word of advice.

"Sleep while you can.' But where? How? We set watches and stretched out on the ground. There was nothing else to do, and it seemed particularly unpleasant and soiled ground. But at midnight the lighters commenced to dump their freight, and we didn't have to worry about getting to sleep after that.

From then until the next night the details worked, sorting, checking, and wrangling with ambitious people from strange organizations. We got our barrack bags, trunks, bedding-rolls, and boxes of equipment piled in the sheds, Then the details were marched out of the dusty yard and back to the boats in time for supper and a bath.

The rest of the regiment, meantime, had stretched its legs for two hours, doing a sort of Cook's tour of the town and its neighborhood. They had come close to the French and had been able to judge how much of young France was at war. They had set eyes for the first time on Hun prisoners marching under guard through the streets.

We became aware at once of a distressing habit of French children. Three English words they all know: Cigarette, Penny, and—Good-by. We never could understand why, when they probably meant "hello" they always gave us a farewell. Or after so much war had even the children become fatalistic and a trifle cynical? It was not, we realized later, a local habit. Marching into some places it was a most depressing one.

Cigarettes and pennies we gave them until the demand threatened our own supplies. At the close of that second night in Brest we were convinced, in spite of its nearly voiceless welcome, that France was deeply grateful we had come. No one seemed to know exactly what the immediate future held for us. After our seven months' training at Upton we realized we were far from fit for the line. It seemed certain that we would go to some training camp for a few weeks' instruction in the real things. We under stood that men were needed and that we would be sent up, as soon as possible.

We were told that night that we would march the next morning to a camp four or five miles from Brest at a place called Pontanezin Barracks. It was, we were informed, known as a rest camp. That sounded enticing, and we were up early, and trooped off the boats, and marched up the long hill and into the open country.

According to the information gathered by the soldiers nearly everything in France was built either by Caesar or Napoleon. Pontanezin went on Napolcon's score card. From a distance it was entirely picturesquc. More intimately it developed white-washed buildings, like barns within, and arid, dusty courtyards. We congratulated ourselves when we learned the barracks were full, and that we would be quartered in tents in a pleasant grove to one side.

The grove had the appearance, in fact, of a rest camp. As it turned out, the name was as perverted as “shirt, under."

What with getting settled, posting guard, drawing rations, setting up kitchens, preparing to police on the morrow, accepting the omnipresent casual, and returning the same, it was dark before the regiment had time to breathe. Still the night loomed restfully. Then the night descended and brought new demands. Orders came. Battery A would break camp at 4:30 A. M., because it was to travel with the 304th Field Artillery, and the brigade was moving at once. The rest of us would march back to Prest at 10:30 in the morning. Then we did have a desti nation! Some located it on the Swiss border. Others in something they called the forward training area. A third group spoke of the vicinity of Bordeaux. It carried off the laurels. We were bound for the Champ de Tir de Souge.

Weary-eyed we turned our backs on our sylvan rest camp, and tramped to the Brest railroad station. It was here that most of the regiment saw for the first time the now familiar Hommes and Chevaux palace cars. The regiment that pulled out ahead of us had them. Our train was composed of third class carriages, and we laughed at the other fellows while we munched our luncheon of bread and corn willy in the railroad yards.

“Those bullies are traveling like a lot of cattle," one heard. “We can sit up and play cards and look out of the window—"

Perfectly true, but after one experience you should hear how eagerly we would ask on the eve of another journey if we weren't going to have Hommes and Chevaux.

“Sardine boxes are all right for sardines," was the verdict on third class carriages, loaded to capacity, after that first ride, "But they didn't give us any oil."

It was seldom necessary to fill goods vans uncomfortably, and you could stretch out and go to sleep. In the third class carriages there were nearly always broken windows. In the goods van, if it got cold, you simply shut the door. That first trip, however, we piled in thankfully, and had our first doubt when we realized how little room there was for stowing equipment.

A number of small boys from the summit of a neighboring wall watched us entrain. Proudly they chanted for us that hap-hazard Marseillaise of the American soldier.

"Hail! Hail! The gang's all here."

And when the train started a little after two they followed us with the inevitable "good-by" which rose to a supplicating shriek. The placid and picturesque landscape of Finisterre and Brittany was a little unreal. Many of the regiment were seeing it for the first time. After the cramped voyage and the thorough rest at Pontanezin such a journey seemed like a holiday. We had been afraid of starvation, and had bought here and there. We found, therefore, that we had more than we rcally needed to cat, and at every station there were carts and stands loaded with fruit and cakes. We always descended to exercise what French we had or to acquirc some. In return for cigarettes we get the beginnings of a vocabulary,

France, clearly, wasn't starving, nor was it going thirsty. Wine was forbidden on the train. A guard was set at each stop with instructions to see that no one carried bottles aboard. He couldn't have eyes in the back of his head, however, and the French thought it very funny to help fool him. There was plenty of opportunity, for water was allowed, and the faucets marked "Eau Potable” were often at some distance from the train. There were usually vendors of stronger stuff about these places. Coming back, men's coats bulged oddly. As the train rolled on the shattering of glass now and then on the right of way was at least suggestive.

If the stuff got aboard it didn't seem to do any damage. There was no disorder. The customary songs didn't increase in volume or expressiveness.

We enjoyed the scenery, commenting on the quaint and calm costume of the Breton peasant, forgetting almost that we were at war, until just at dark a peculiar and riotous alarm recalled us.

Confused cries ran along the train, indistinguishable at first, but carrying a note of excessive tragedy. They rose. A pistol shot rang out. Another. A salvo. A bugle blared.

We sprang to our feet and stared from the windows. The train bowled through a cutting. Heads leaned from every window. Nothing more unusual was visible. The racket continued, and out of it slipped words that could be grasped.

"Stop the train! Stop the train!"

The plausible explanation sprang at cveryone. Someone had fallen out. Back on the line must lie a still form. But a calmer mind reasoned. In time of war, its logic ran, troop trains, squeezed into schedules with difficulty, don't stop and block things for the carelessness of a single man. Such a catastrophe would be treated by sending back word from the next station. No, the calm reasoning went on, it must be something far more serious than that. We believed it when word came along that The Great wanted the train stopped. We could hit on only one explanation. The train must have broken in two. An express thundered behind us. We were, we learned later, to get out of its way at the next stop, a few miles ahead. The fate of that motionless string of cars, packed with, perhaps, half our companions, was terrible to contemplate. So an officer and several men, crawled forward over a string of goods vans to the locomotive. The execution to their clothing was appalling. But they persuaded the driver to stop the train, although he seemed in danger of a fit before he yielded, shouting things about the express that our amateur interpreters had difficulty with. They gestured rather more than he did and got their way. The train stopped. The engine driver animated himself volubly. He saw that the train had not broken in two. He sprang to the throttle, threw it open, dashed us into the station on a side track, and pointed to the express which roared in a little after his.

Colonel Doyle, Majors Johnson and Wanviy, and the train interpreter hurried to the engine, while we waited to learn the truth. But there came the answer himself across the tracks—a wobbly soldier just descended from the express and supported by a medical orderly.

There is, after all, a great deal of anti-climax about war. The present case failed to give us the thrill we had anticipated. It boiled down to indigestion, rather severe, still vulgarly gastric. It bad struck the wobbly soldier at the previous station. Captain Parramore had instructed one of the medical orderlies to take him from the train and care for him. The train had departed sooner than anyone had expected, leaving the sick man and his attendant. They hadn't worried because they were told they could catch us by the express. Captain Parramore had told the Colonel they had been left. After our premonitions we didn't miss a more dramatic dénouement.

Such incidents break the monotony of a journey. A different sort spelled variety the next morning. We rolled into Nantes about seven o'clock after a cramped night. We weren't surprised to learn we would be there until eight, for Nantes is a large city. A warm breakfast beckoned. Some of us snatched it in nearby cafés, and hurried back to the train which left without any particular warning at 7:50. Men scurried from every direction and scrambled through the open doors of the compartments. We made a hurried check. Everything was all right except that neither battalion bad a commander or an adjutant. Majors Johnson and Wanvig and Captains Reed and Delanoy had breakfasted not wisely but too well. What the colonel thought about it we never heard. There was, this time, no effort made to hold the train for the missing, although their misfortune, too was vulgarly gastric.

So we crossed the Loire and turned to the south through Les Roches Sur Yonne, La Rochelle, and Rochefort, where our missing officers rejoined us, grateful to the French for a travel order and convenient express trains. They looked so well shaved and comfortably fed that we gathered they wouldn't make any trouble for the railroad company about leaving them.

At Saintes on the Charente, where we stopped at dusk, the war seemed to come closer. We all piled from the train and had half an hour's brisk march through the picturesque little city. But it was the railroad station that impressed us most. Permissionaires swarmed there in faded blue uniforms and battered helmets. Some were smiling and happy, talking with vivacity and wide gestures to civilians. Evidently they had just arrived. The soil of the front line still stained their clothing. Others, far neater and encumbered with equipment, did not have much to say. Clearly enough their holiday was over. They were going back to the thing that waited for us.

We tried to visualize ourselves within a few weeks at one with these men whose faces were bronzed and sadly wise. We tried to approximate their emotions. Our next train journey, we remembered, would be in their direction. There was a fascination in standing close to them and wondering.

After another cramped night the spires of Bordeaux greeted us across the vineyards of the Gironde, and at seven o'clock the train halted with a definite jerk at the railhead of Bonneau.

Lt. Klots, who had come as our advance agent, met us and guided the tired column, bent beneath its packs, down a road that entered a pine wood.

"It looks like Upton," we said.

But these evergreens were larger, the sand was deeper, and at a crossroads was an estaminet with tables and chairs set on the edge of the road.

It was only two miles to an arched gateway, summounted by the republican cock and the legend: "Champ de Tir de Souge."

Within we found endless rows of French barracks, painted brown. As we marched along the main avenue we noticed inscribed panels above the doors, reciting the valorous death of some officer or non-commissioned officer who had trained there.

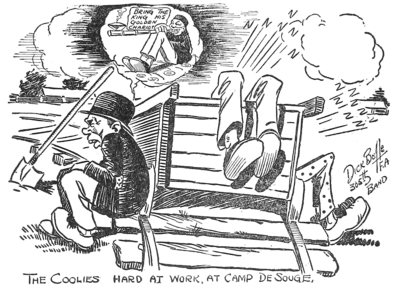

By noon assignments were made. Barrack bags and baggage had arrived. Except for the sand, we gathered, Souge would not be uncomfortable. We were vastly amused at hordes of French coolies, parading around beneath umbrellas against the sun, or languidly making a pretence at work.