Journal of the Straits Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society/Volume 1/Geography of the Malay Peninsula, Part I

GEOGRAPHY OF THE MALAY PENINSULA.

BY MR. A. M. SKINNER.

[1]PART I—CARTOGRAPHY.

Read at a Meeting of the Society held on the 8th July (see also p.5)

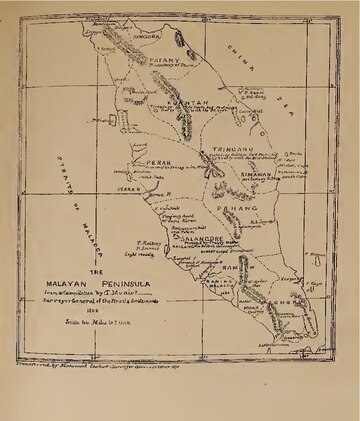

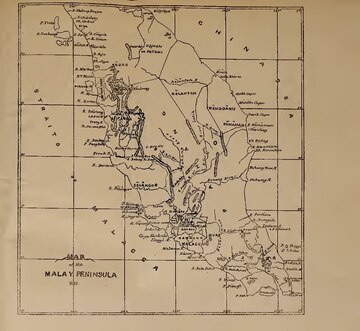

Some of the most interesting and valuable contributions to the Journal of the Indian Archipelago, more especially during the earlier numbers were upon the Geography of the Peninsula. Mr. Logan himself frequently returned to the subject during the years 1846-53. Those papers contain a fund of minute topographical details, the itineraries of at least six important journeys in the interior, and, in short, much of the rough material for a Map of the districts which lie nearest to our Settlements. To a fuller consideration of these records I will presently return; but first as to the Maps of the Peninsula. Unfortunately at that period of activity no such Map was compiled. Prior to Sir A. Clark's time, as far as I can discover, but one official map was produced—if a mere outline sketch can be so called. This was first published in 1862, apparently for the use of the Political Department of the Indian Government in connection with the publication of the "Treaties and Sunnuds (1863.)" It is now better known as the map bound up with our first Colonial Blue-Book (C.--465,1872) on the Selângor bombardment. Mr. Moniot, at that time Surveyor General of the Straits, prepared it; but he made little or no use of the information obtained ten years before. I was puzzled at first to discover what guide he had followed on the subject, much of the detail in his sketch being in express contradiction not only to that collected by Logan, but also to the notorious facts of the case. I think I have now discovered the original in an old Dutch Map of Sumatra, the Peninsula and the Straits of Rio, stowed away in the Survey Office, and bearing two dates, 1820 for the Straits of Rio, and 1885 for Sumatra. There is nothing to show to what date the "Peninsula" portion of it should be referred; but it may be gathered, from the boundaries assigned to Province Wellesley, that it was compiled by the Dutch authorities between 1800 and 1828-probably during their brief re-occupation of Malacca. This map is almost exactly reproduced, though on a smaller scale and with fewer particulars, by that to which Mr. Moniot's name is attached; a fact which will sufficiently indicate how inadequate such a sketch must be at the present time. But it was not till after the Perak War (June 1876) that any better, or indeed any other map of the whole Peninsula was to be obtained; and I have therefore had a copy made of it, as well as a copy reduced to the same scale from the large map now under preparation. I had intended to contrast them in one and the same sketch; but on second thoughts it will be simpler to keep them separate; and the later, and certainly more correct map, though too small to give many names, may perhaps be useful for reference. It marks roughly the outlines of the Malay States, the mountain-chains, and the river systems, as known up to the present time (1878); and also the routes of the principal journeys in the interior of which we have any record.Having described at some length the only official map published during the ninety years our Government had been paramount in the Straits, prior to Sir A Clarke's intervention in the Native States of the Peninsula, I may here refer more briefly to what has been done since that time. Immediately after the Pangkor Treaty (January 1874) a party explored the route from Larut to Kwala Kangsa, and thence down the R. Perak to the sea. This may be considered the key to the geography of Perak in the North, just as the common source of the R. Muar and the southern branch of the R. Pahang is the key to the geography of the South of the Peninsula, and the knowledge of the country between the Northern branch of the R. Pahang and the R. Kelantan, is the key to the geography of the Interior of the Peninsula. On both these latter districts much light was thrown in 1875 by the journeys of Messrs. O'Brien and Daly and M. de Mikluho-Maclay respectively. Thus within 18 months of the Pangkor Treaty, our Government had obtained more important information than had been collected during the ninety years prior to that event. I will refer to these journeys at greater length presently; I only mention them here in explanation of the two official maps published in 1876, which mark a great advance in our knowledge of the country. The first in point of date, and, strange to say, the most accurate in every respect, is one which apparently owed its existence to the Perak war. It was published by the Home Authorities in Blue-Book C. 1512 (June 1876) and was "compiled from sketch surveys made by Capt. Innes, R.E., Mr. J. W. Birch and Mr. Daly"—scale 15 miles to 1 inch; and it was "Lithd. at the Qr. Mr. Genl's Dept. under the direction of Lt. Col. R. Home C.B. R.E." It is much to be regretted that no separate copies of this excellent map were procured. The similar but less correct map published on the part of the local Government, and received out here towards the end of 1876, met with a rapid sale, the whole issue having long since been disposed of. Many applications have been made in vain for further copies, especially during the present year; and I feel little doubt that, apart from the crying want of a good map on a large scale for educational purposes, there will be numerous private purchasers to recoup any expenses of publication which may thus be incurred by Government, or by the Society if disposed to venture on such an undertaking. And even if copies could still be procured of either map of 1876 I should recommend a re-publication; so many of the inaccuracies having now been corrected, and no small portion of the blank spaces having been filled in with fresh particulars.

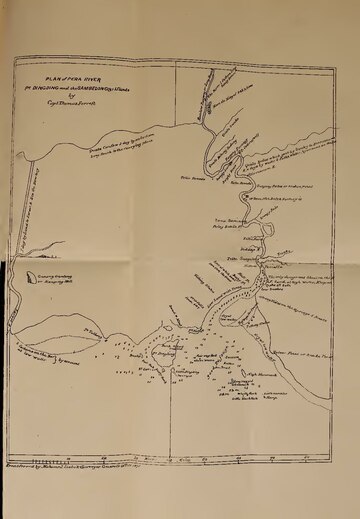

Before I turn to the explorations, extending over a period of half a century (1825-75), to which such knowledge of the Peninsula as we possess is mainly due, I will briefly refer to the charts of the old Navigators, so far as I know them. But I must here state that our Raffles Library is extremely deficient in old "Travels," and that I cannot hope to give anything like a complete view of the growth of our knowledge. The earliest accounts of the Peninsula, as a whole and accompanied with Maps, are those of the French traveller de la Loubère, and the English navigator Captain Dampier,[2] who appear to have been in these parts at the same time (1686), though without meeting or even hearing of each other. I have not succeeded in finding a copy of Loubère's Map, but Major McNair, who saw a copy in England, thus refers to it in his book "Sarong and Kris" (p.315):—"In De La Loubère's book is a quaint but very correct Map of the Malayan Peninsula, prepared by M. Cassini, the Director of the Observatory of Paris in 1688, from which is gathered the fact that Perak then continued to be looked upon as second only to Malacca on the Western coast. The River Perak is not very correct in its representation, being made more to resemble a tidal creek. This is doubtless due to the information received that the rivers to the north joined the Perak, which, in the case of the Juru Mas and the Bruas, is very nearly correct." In Dampier's Voyages (Ed. London, 1729) I find three sketches of the Peninsula. Two of these (vols. I and III) are introduced in general maps. But the sketch in vol. II is on a larger seale and is confined to the Straits. It is curions that while both the former represent the Peninsula as widening towards Malacca and Johor, the latter, though ten years earlier in date than the map in volume III, yet gives its true shape. But the names on this sketch are most perplexing, there being indeed but five that can be safely identified,—R. of Quedah, R. of Johore (the only Native States shewn) Malacca, R. Formosa and Straights of Singapore (round St. John's). The R. Perak is marked, without being named, as a great estuary some 5 or 6 miles wide, running for a distance of 30 miles N. E., with islands lying in it of a larger size than Penang and the Dindings. It may be conjectured that this is intended to represent the whole water-system, including R. Kiuta and Batang Padang. There is also the same confusion with regard to a supposed connection between the R. Perak and the rivers to the North, that Major MeNair noticed in Loubère's map; the river Songi-bacoas (Baroas?) is represented as joining the Perak about 30 miles from the sea. The later Dutch map, already referred to, makes the same mistake, probably through copying these older maps. It is at the same time possible that the Breas was once connected, artificially or naturally, with the R. Perak; and this supposition is to some extent supported by the unusual quantity of mud silted at the "Kwala" of that river, which is out of all proportion to the size of the present stream of the Bruas. It is more probable however that the supposed junction of the Perak and Bruas was intended to represent the old connection between Larut and Kwala Kangsa; as represented in the map I come to next, that of the R. Perak by Captain Forrest compiled from his own surveys 100 years later, in 1783, (voyage to the Mergui Archipelago, London 1792.) This tracing gives the lower part of the river very correctly. Col. Low who was sent to Perak on a political mission in 1826 acknowledges that it was by the help of this chart alone that H. M. S. "Antelope," 20 guns, got into the river (I. A. Journal vol. IV. p. 199). Above the Dutch Factory, which Capt. Forrest refers to as being "re-established" at Tanjong Putus, the plan of the river gets much confused. This portion of the journey was performed "in a country covered boat in which the writer went up "to pay his respects to the King of Perak;" and from this point Capt. Forrest evidently found it more difficult to take correct observations. He seems to have met the King at Sayong, unless he has mistaken the situation of K. Kangsa, which he writes "Qualo Consow," and marks as an extensive tributary having at two days' distance a "Carrying Place one day by land to Larut River." I am inclined to think there has in fact been some confusion between this supposed tributary, and the bend to the North which the main stream takes near this point. If this surmise is correct the residence of "the King" was probably at Alahan, where Col. Low found the Court 43 years later. The only name given in its vicinity is Rantau Panjang, probably Pasir Panjang. But this tracing of Perak, before the Siamese invasion, is so interesting that I have had it copied, and readers can form their own judgments on these points. It will be seen that the lower part of the river is given very correctly, and that most of the names can be identified. All reference to the Bruas, as connected with Ulu Perak, has now disappeared; and it is curious that the mistake, as it undoubtedly was then, should have reappeared many years later in the Dutch Maps already referred to. Mr. Moniot might have have been warned by this to distrust so unsafe a guide. Col. Low, it may be remarked, also overlooks the importance of this portion of Forrest's sketch. The only reference he makes to the route from Kwala Kangsa to the sea is in the following passage from his account of Ulu Perak as "described to me by Natives, and by the Chinese;"

"From Quallah Kangsan there is an elephant road to Trong. The first March is to Padang Assun. The second to Pondok, chiefly across rice grounds. Here the population may be rated at 1,000."

It is possible that Col. Low. here speaks of the Kwala Kangsa, which he has referred to just before as near Kendrong; and that there is some confusion between the Trong near Larut and the Trong to the north of Kedah.

Between the date of Capt. Forrest's engraving (published in 1792) and Mr. Moniot's (published in 1862), no map with which the Malay Geography is specially concerned was published. There are however two M. S. drawings to speak of, Low's and Burney's, which have also been preserved in the Survey Office, originally at Penang and of late years at Singapore. The former bears date 1821; the latter is undated, but was probably compiled at the time Captain Burney negotiated the Siamese Treaty of 1826. Col. (then Lt.) Low confined his sketch almost entirely to the northern provinces of Siam. Captain Burney's tracing includes Kedah, Singora, and Patani; and the care with which he compiled it may be gathered from the "memorandum" at the side, from which I quote the following passage:—

"The Coast and Islands between Pal Phra and Prince of Wales' Island are set down after comparing Horsburgh's, Forrest's, Blair's, Heather's, Iuverarity's, Martin Lindsay's and Dupres de Mennevillete's Charts with maps and descriptions obtained from several Malayan aud Siamese Pilots, as well as with what was observed by ourselves during our passage to and from Pungah. Of all the European Charts; the two oldest, Daprès de Mannevillite's and Martin Lindsay's, appear by far the most correct. Some information also respecting the towns on the Gulf of Siam and the country round Pungah, was received from Padre Juan, a Native Catholic Priest residing near that town; and it is but just to acknowledge that very great assistance was derived during the progress of the Mission, from the descriptive sketch of the Malayan Peninsula compiled by Mr. John Anderson, Malay translator to Government."What Capt. Burney says about the superior correctness of the older charts, now holds good about the older maps; for nothing has been produced since his date that can vie with his own sketch in practical usefulness or careful execution. Indeed the old Navigators, the Dampiers and Forrests of the 17th and 18th centuries, appear to have been succeeded of late years by the Indian Officers, until recently stationed or employed in these parts, Col. Low, Capts. Burney, Newbold, Begbie, &c., to whose eagerness for knowledge we owe so much of the little information we possess about the Malay Peninsula.

From the time when Logan's Journals ceased to appear a long night settled down upon the Straits, lasting some twenty years. It is difficult for those who were not here before 1874 to realise how little was then known of the Peninsula. Kwala Kangsa and Selâma were names unknown; S. Ujong and Sri Menanti were little better; Muar, Birnam, Perak, and Kurau could not then be named without an affectation of special, not to say pedantic knowledge. I do not believe that any person then knew of the true course of the R. Perak, or of the short route from Larut to Ulu Perak, which I have already called the key to the geography of that part; and as to which it has been seen that Captain Forrest ninety years before had possessed some information. But within two years of the Pangkor Treaty, thanks to Sir A. Clarke's initiative and the development of events, this state of things was entirely changed. Information had been collected in many districts. The journey from Larut to Perak, and down the latter river, which was performed in 1874 by Messrs. Dunlop, Swettenhamn and Pickering, effected for that part of the Peninsula, what the journey by Messrs. Daly and O'Brien, up the Muar and down the Pahang, effected for the true understanding of the relations, whether physical or political, which exist between the States of Johor, Pahang, and the Negri Sembilan, in the South of the Peninsula. The journey of M. de Maclay in 1875 must also he mentioned, as throwing light on the unknown Central regions. Of these three journeys, so important to our Cartography, some record should here be made; more especially as no account of them bas ever been published in a permanent or generally accessible form. I have therefore selected the most striking feature of each account to conclude this paper. But it would be invidious not to refer also to certain earlier journeys, viz: that of Mr. Charles Gray (via Malacca, Naning, Jumpol and Pahang in 1825, I. A. Journal vol. VI, p. 369); of Mr. Logan (via Singapore, Indau, Semrong, Blumut, and Johor in 1817, I. A. Journal II, p. 616); and of the Rev. Le Favre (via Johor, Benut, and Batu Pahat in 1846; and again via Malacca, Rambau, Sungei-Ujong and Jelebu in 1847, I. A. Journal vols. I & II). I hope to avail myself largely of these accounts in Part II of this paper, when I treat of the geography of each State; but it is the less necessary to quote from them here, as they are already preserved in an accessible form.

I will however take this opportunity of recommending their careful perusal to all those who are good enough to assist in rendering our new map more complete. I find that a good deal of the information furnished from time to time obviously lacks the advantage of having undergone comparison with the local details collected by earlier writers, and this is a grave loss when the writers are such as l'abbé Favre, and the late Mr. Logan.

I. (Extract from the Journal of Messrs. Dunlop, Swettenham and Pickering, during the crossing from Larut to K. Kangsa February 12, 1871.)

"We started at 1.30p.m.and within half an hour, got into the finest jungle we have yet seen, crossed incessantly by a beautiful clear stream. This jungle was filled with the brightest scarlet and yellow flowers; there were numbers of orchids. After continually ascending till we came to the source of the stream, we began to descend again, following the course of another stream running in the opposite direction. All this time we had been going through a narrow valley, Bukit Berapit forming one side of it, and as we came out into the open, we stood in front of one of the most extraordinary rocks I have ever seen, called Gunong Pondok.

"We had just come out of a narrow valley, filled with dense jungle and not very high bills on each side. Coming out of this, the valley now level and comparatively clear, widened out abruptly, so that it became an extensive plain. Close in front of us, rather on the left, rose as it were straight out of a plain as level as the sea, a large rock, some 800 feet high, partly covered with trees, partly bare rock in sheer precipices."

"The rock itself is formed of limestone, and it is that curious looking hill, commonly called Bukit Gantang which, when seen from the sea, forms the chief land mark for entering the Larut river. The only hill I have seen at all like it is "Elephant Mount" in Kedah, and we could see that Gunong Pondok resembles the mount, in the fact of its being full of caves. On our right was Bukit Berapit and this stretches away to the right, in a range of gradually lessening hills. Right in front of us, a beautiful valley, some twenty miles long, almost all cultivated or partly so, shut in the distance by the hills in the interior of Perak."

| * | * | * | * | * | * |

February 14th at 11.45 a.m. we arrived within 150 yards of our destination, only to find we were on the wrong side of a wide and deep river. It is no use attempting to argue a point like this, so we undressed and swam across. The others came up and had to go through the same performance. The river we came across was the Kangsa, which here runs into the Perak river, a stream about 200 yards broad; and we are looking forward with considerable pleasure to a three days' journey down it."

II. (Extract from Mr. Daly's Journal during the crossing from Ulu Muar and Jampol to Pahang, 1875.

"I cannot get even our man to accompany us, although we have offered very high wages,—so we are starting by ourselves. This is a drawback to me, as I always like to get some man who can give me the native names of rivers, hills, and kampongs, wherever I go."

"They say, as one of the objections to our going to Pahang, that we cannot find our way through the lake (Tassek Berâ) which we have to cross to strike again the stream that runs into the Pahang river. I apprehend more difficulty in getting the boat over the shoals and snags of the "Ilir Serêting."

"The Malays of this place won't go with us, as they say that they are sure to be killed by the "orang utan" (wild men) of the jungle of Pahang."

"Got the boat cleared out, freshly caulked, and got galas (poles), kajangs, and rudder, and floated her. She seems too large for the work, but "beggars etc."

"August, 16th.—Unable to persuade any one even to help us in getting the boat under way, we started on our journey to Pahang. The party consists of O'Brien, the three police and myself—and provisions for 10 days, viz: rice, tea, a few tins of sardines and powder and shot—relying upon shooting a few pigeons now and then for fresh meat."

"At starting from Kwala Jumpol had great difficulty in getting the prahu over the sandy bars, and, though the distance from the Kwala up the River Jumpol to the place where the boats are taken overland at Penarri is only about 1 mile, we took over three hours dragging the boat. It is a very narrow steam, choked with fallen timber and sand banks overhanging with the mach dreaded thorns, called "unas" by the Malays, that resemble tigers' claws and tear everything they lay hold of. Nearly all the time we were in the water dragging the boat along."

"On arriving at Penarri we took everything out of the boat and carried the things across to the River Ilir Serêting, and in the evening we managed to get fourteen men at ten cents a head to pull the boat across the dividing land from River Jumpol to River Ilir Serêting. I measured the distance from one river to the other,—it is 24 chains or a little more than a quarter of a mile; There is a rise of 25 feet from the river bed up the first bank, and we were a long time pulling the heavy boat up to the level land. Long bamboos were lashed to the fore thwart of the boat and all hands hauled at the bamboos—the knots on the bamboo giving good holding power. It was a fine moonlight night and the excitable Malays worked with a will, making a great noise.

"When we had got the boat across, after two hours' work, and safely deposited in the other river, I sent up a couple of rockets to their great delight and paid them. Gave quinine to a great many who had remittent fever and ague.

"It is a great relief to have got so far, and away from the Kwala Jumpol people who are foolish and suspicious from ignorance, and who were threatening mischief.

III. (From Ulu Pahang to Ulu Kelantan. A short Itinerary, compiled from the note book kept by M. de Maclay, 1875.)

I took about 69 to 70 hours to arrive at the river Tamileng up stream from Kwala Sungei Pahang. The journey was made in a tolerably large flat-bottomed boat, which four Malays pushed forward with long poles, two and two by turns. This kind of transport, which I have met with here, in Johor, Kelantan and almost all over the Malay Peninsula, is used partly on account of the slight depth, but chiefly because of the notable force of the current. In this respect it has a great advantage over the car, for each new push with the pole, holding as it does to the ground, hinders, or at least reduces to a minimum, the backward flow of the current. If, under these circumstances, one reckons the rate of advance at 1 to 1½ miles per hour (which reckoning in any case is not at all too high) then the distance of Kwala Sungei Tamileng from the estnary of the Sungei Pahang (all bendings of the stream included) is about 70 to 80 English miles. Not far from the Kwala Tamileng I found the river Pahang, though somewhat narrower than in its lower stream, was about 40 fathoms wide, or about as broad as in its middle course. At the mouth of the Tamileng on the right bank of that river, lies an important village called Kampong Roh. Here I found it necessary to transfer my rather large covered boat (in which all my baggage, two servants and five Malays had found room) into two small open canoes.

The bed of the river Tamileng is, it must be allowed, in many places rather narrow, and forms numerous rapids (Jeram); whilst in others, owing to the silting of the sand, the water is very shallow. Following the course of the river Tamileng, we passed the sixth rapid, and I reckoned that at this spot we were 250 feet above the level of the sea.

Near the sixth rapid, at the kampong of Pengulu Gendong, I noticed at some distance a remarkable mountain, which was pointed out to me as Gunong Tahan. I believe that from here the mountain could be reached in 2 or 3 days. The bank of the river Tamileng appeared to be tolerably well-peopled, mostly by Malays, but I also remarked several Chinamen among them.

| * | * | * | * | * |

The unexpected visit of an "orang puteh," never seen here before, filled the people with such misgivings that they stood quite dumb, and to all questions that were put only answered "tra tau" "baru datang" or "bulum tau." It was often difficult not to take people, who became thus suddenly dumb, for regular "mikro kephalen." After I had followed the Tamileng up its course for 22 hours, I came to the mouth of a still smaller stream, the River Saat or Sat. From here Kwala Sat there are two ways further up the river Tamileng; eastward, a way to Tringgano (arrived at after a journey of 3 or 4 days.) The stream Sat, flowing in a northerly direction, marks the way to Kelantan. From Ulu Sat it took me 6 hours more to reach the small Kampong Chiangut, consisting of two huts. Further, the water of the Sat proved too shallow even for the smallest canoe, such a one as is only fit to carry two men and some baggage. From Chiangut there is a footpath of only 8 or 9 hours walking to Kwala Limau, which belongs to the water-system of the river Kelantan. From Chiangut following the course of the streamlet Preten (a tributary of the Sat) and always keeping in a northerly direction, one reaches further up to Batu Atap.

This hill forms the political frontier of the territories Pahang and Kelantan, and at the same time the watershed of the two river systems (R. Pahang and R. Kelantan). A second hill must be crossed, of much the same height, about 100 feet above Chiangut. From here, still going northward, I reached the small river Limau at the point where it becomes navigable, and where the travelling further up the stream is usually done in a "raket" or "dug-out," made of bamboo. Kwala Sungei Limau lies about 400 feet lower than Batu-Atap. From Kwala Liman it takes 5 hours to follow down the small river Trepal, to its mouth in the river Badokau, which like the first two is still very narrow and full of rapids. After eight hours more in the rivers Badaku, Ko, Retou one reaches the embouchure of this latter into the Lebe, from which point a convenient water-way is again reached.

Not far from Kwala Retou the R. Areng also empties itself into R. Lebe, on the banks of which I met a considerabile number of Orang Sakai.

Upstream on the R. Lebe one comes to Kwala Siko. The Siko, which at its mouth is wider than the Lebe, comes from W. S. W. and forms the water-way to Selangor, and also to Ulu Pahang; but it takes a greater round than the way I followed (Ulu Tamileng to Ulu Lebe.)

The stream thus formed by the junction of the Lebe and Siko is called the Sungei Kelantan. In niue hours one comes to the considerable settlement of Kota Bharu, the residence of the Raja of Kelantan; and an hour and a half further down, to Kwala Sungei Kelantan.

- ↑ It was my intention to have dealt with the whole subject in a single paper, but so much fresh information is being collected in various quarters that I find it advisable to postpone dealing with the Geographical details till the next number.-A, M, S.

- ↑ Our English Cosmographer Hakluyt, who, like Barros, never travelled himself but devoted his life to promoting the discovery of unknown lands was probably the first Englishman to map out the Straits in his "very rare Map" of 1599, a copy of which is in the British Museum, In the second volume of "Navigations," published the same year, he refers to "the isles of Nienbar, Gomes Polo, and Pulo Pinnom" (Pinang ?) to the maine land of Malacca, and to the kingdom of Junsualaon." (Junk Ceylon?)