Life with the Esquimaux/Volume 2/Chapter 5

CHAPTER V.

Chewing old Boots—Formation of Icebergs—Innuits good Anatomists—Koojesse draughting the Coast—Sarah G.'s Cape—Iron Island—Arrive at Jones's Cape—A Settlement of Innuits—Native Monuments—Dental Mill for trying out Oil—Arrive at Ming-u-toon—Great Rise and Fall of Tides—Bones of the Whale and other Animals—A Grave—Laborious and difficult Work—Arrive at Waddel Bay—Meeting with old Artarkparu—A persevering and industrious Cripple—Proceed toward his Village—Annawa and other Natives there—Women busily engaged in sewing Skins—A Good Feast—More information about Frobisher's Expedition—Ascend a Mountain—Remarkable Features about it—Large Caverns—The Aurora—Curious Phenomena.

The following day, Monday, August 12th, 1861, Suzhi and myself remaining at Oopungnewing, the rest of my company set out in the boat for the main land on a tuktoo hunt. My time was occupied in taking observations, writing, and examining the island, while Suzhi was busily engaged in dressing sealskins for jackets, and "milling" old native boots—that is, making the soles soft and pliant by chewing them.

During the day I heard some extraordinary noises, like the rumblings of an earthquake. I had noticed the same on our way from Cape Cracroft, but now the sound was so loud that I could not help asking Suzhi if she knew what it was. She replied that it came from the Kingaite side of the waters; and, from what I afterward learned, it must have been caused by large masses of ice—icebergs—from Grinnell Glacier falling into the sea. The distance traversed by the thundering sound thus occasioned was about forty miles. At other times, while in this bay, I have felt the earth tremble from the same cause.

In the evening Suzhi and I took a walk round to the north side of the island. We had not gone far when she asked me, in her native tongue, "Do you see walrus?" pointing to a long white line running up the mountain's side. I looked, and at first supposed it to be a vein of quartz running up among the dark, moss-covered rocks; but, on closer inspection, I found it to consist of over a hundred walrus jawbones, placed in line about two feet apart. Some parts of each were white as the

SUZHI'S BOOT "MILLING."

snows of Kingaite, but a considerable portion was covered with thick black moss. What this singular arrangement meant I had yet to learn.

We next came to a spot situated by the margin of a grass-plot, completely covered with bleached bones of seals, walrus, whales, and tuktoo. Ask an Innuit to what animal this and that bone belonged, as you pick them up, and he or she will tell you at once, the people being in reality good natural anatomists. We passed on half a mile, and reached a point of high land, which looked out toward Niountelik, but could see none of our party returning. It was then ten o'clock; the night was fine, and a few stars were visible, but it was not yet late enough in the season to bring out the host there is above. Koojesse and his party returned about midnight, but wholly unsuccessful, though they had seen eight tuktoo. This, however, was not of serious importance, as we then had an abundance of provision.

We resumed our voyage on the morning of the 13th. Twice before leaving the island I again heard the loud thunderings already alluded to, and felt the vibrations of the very earth itself. What could this be? Was there a volcano on the Kingaite side, or were its mountains of ice falling from their precipitous heights?

It took a long time to strike tupics, and get everything into the boat and in order. Last of all Suzhi brought aboard the Ninoo's bladder and the charms, and placed them at the bow of the boat, mounted on a stick. Without them I strongly doubt whether the Innuits would have considered it safe to go on. Our course at first led toward Sarah G.'s Cape[1] (Twer-puk-ju-a), the way by which I went when making a hurried visit four months previous. Strangely enough, as it now seems to me, and no doubt to my readers also, I felt as safe and contented as though I were with civilized men instead of being alone among the wild, independent natives of that frozen land. I even did not hesitate to depend upon them occasionally for some of the work I wanted done in the way of delineating the coasts as we passed along. Koojesse—the really gifted Esquimaux—now and then acted as my assistant draughtsman, his sketches, however, being afterwards carefully examined by me. While I sat in the boat's stern steering—a position which allowed me to have good views of the land—he sat before me actually laying down most correctly upon paper the coast-line along which we sailed, and with which he, as well as Sushi and Tunukderlien, was perfectly familiar. There was not a channel, cape, island, or bay, which he did not know perfectly, having visited them again and again.

One unacquainted with a new country would often make great mistakes by charting nearly everything as main land, where portions of it might be islands, failing also to give proper depths of inlet coast, unless he had time to visit every locality. On my present trip up the bay I had not that time, and therefore I reserved—to be made, if possible, on my return—a closer examination of places now draughted down under my eyes. During all this voyage, however, I kept up a constant record of distances run and courses steered, and made as frequent landings for taking observations for latitude, longitude, variation of the compass, &c. as the circumstances would admit.

Between Oo-mer-nung Island and Iron Island—the former in Wiswell Inlet[2] and the latter near Peter Force Sound[3]—a heavy sea prevailed, rolling in from the northwest, and it was astonishing to see my heavily-laden boat ride so well over the dashing, heaving, irregular waters that came upon us.

Iron Island is an interesting place, and I gave it the name because of the resemblance of its rocks to oxydized iron. Innuit monumental marks, made of the huge bones of the whale, were upon the island. Here also, on our landing, was found an excellent piece of timber—live oak—which probably belonged to the wrecked Traveller, already alluded to. It was dry, and so large and heavy that one of the Innuits could only just carry it. We took it away in the boat to use for fuel; and on sawing off a portion, I found it as sound as it had ever been.

The place where we determined to make our next or fourth encampment was called by the natives Toong-wine; this I named Jones's Cape,[4] and here we expected to find a settlement of Innuits. Before we reached it a breeze sprung up and helped us on. A snug little harbour appeared ahead, and an Esquimaux was observed on an eminence near the shore, eagerly watching us. As we drew near, all the inhabitants appeared to be out on the rocks to await our arrival; and when we landed, such as were able cheerfully assisted in getting up our tents and in other work. Most of those I now saw were familiar faces. They belonged to the party which I had visited the previous April farther up the bay. But Sampson was now away on a tuktoo hunt. He had recovered from his illness already mentioned; the report of it brought us was doubtless exaggerated, being founded on an incorrect idea of the disease. The old ladies whom I then met—Shelluarping, mother of Kookin, and two of her friends—who were so pleased at my eating with them in the genuine Innuit style, were here, and gave me a hearty welcome. Ookgooalloo was sick, and I therefore visited him as soon as I could. I was guided to his tupic by his groans; but when I entered and asked the name of the sufferer before me, I was surprised to learn that it was my old friend, so sadly changed. Sickness seemed unusually prevalent; indeed, the only three men of the place were so feeble that not one of them could go out hunting or sealing.

At this spot were some remarkable monuments of stone, one being in the form of a cross, and about six feet high.

In the evening, being in want of oil for my lamp, I went to Koojesse's tupic to obtain some. There I beheld a scene for a picture:

Koodloo and Charley made search, found seal-blubber, brought it in, and passed it to Suzhi, who was in tuktoo, as I may say—that is, a-bed. Of course, like all Innuits when in bed, she was entirely nude; but she immediately rose on her elbows, and proceeded to bite off pieces of blubber, chewing them, sucking the oil out, then spirting it into a little cone-like dish, made by inverting the bottom of my broken tin lamp

INNUIT MONUMENT AT TOONG-WINE—JONES'S CAPE.

In this way she obtained with her dental "mill," in less than two minutes, oil enough to fill two large-sized lamps. Koodloo and Kooperneung were standing up in the tupic at the time, I was seated with Akchukerzhun at my right, on tuktoo, by Suzhi's head, waiting for my lamp, while Koojesse and his partner, Tunukderlien, were at my left, wrapped in Innuit slumbers. It was a novel scene, that of Koo-ou-le-arng's operations in grinding blubber for oil; in particular, the incidental exhibition of what Burns describes as

"Twa drifted heaps, sae fair to see,"

exaggerated in size, as is the case with most Innuit women, struck me forcibly. The whole scene, though so strange to me, was taken by the Innuits as an every-day affair, and quite a matter of course.

The Innuits certainly show peculiar skill in thus expressing oil without allowing a particle of moisture to come in contact with it. It may be doubted that such a thing is possible, but so it is. My replenished lamp burned brightly, allowing me to write up my diary with great facility.

Jones's Cape was really one of the finest places I had seen in the North, not excepting even Greenland. Force's Sound is nearly surrounded by magnificent mountains, and is sheltered from winds and heavy seas by a number of islands. There is an excellent entrance for ships, and the harbours, I thought, might rival any in the civilized world. If a colony should ever be planted in those regions for the purpose of Christianizing the people, Jones's Cape presents many of the advantages desired.

On the following morning, August 14th, I took Koojesse and ascended a mountain in the rear of our encampment. The view was very extensive, and I could plainly see more than fifty miles of Kingaite coast, the nearest point being distant some thirty miles. On my way I observed a considerable quantity of the stone I had noticed upon Iron Island, and I also saw many small pieces of limestone on the very summit, about a thousand feet above the level of the sea.

I remained at Cape Jones until noon for the purpose of obtaining a meridian observation. While making this I was amused to see the astonishment depicted in the countenances of the Innuits of the settlement around me—as far, at least, as they ever do exhibit unusual interest in any subject.

At 12.30 p.m. we again set out on our expedition, directing our course westerly across the east arm of the bay. The natives assembled in large numbers to bid us ter-bou-e-tie, which may be rendered thus: "Good-bye, our friends. May you fare well." We rowed for about half an hour, when, finding the sea too heavy for our frail boat, we hoisted sail and steered direct to the middle of the island—Nou-yarn. At about 2.30 p.m. we stopped at a point of the island, and Koodloo went ashore, shortly returning with a shoulder-load of live oak for fuel, which was clearly part of the Traveller wreck.

From Jones's Cape we had a hard and tedious passage across the mouth of the sound, consuming two and a half hours in making good three miles. The wind freshened to a strong breeze, and for an hour we were in the "suds." Every few minutes a "white-cap" was sent with all force into our boat, thoroughly wetting us and everything. Tunukderlien was kept constantly baling, and Kooperneung tucked his nuliana under the folds of his oil jacket to keep her from the overleaping waves. The sheet was not made fast, but was kept in the hands of some of the lady crew, ready at any moment for the word—Let go!

The passage was by no means free from danger; but God rules the waves, and He brought us safely over. A light shower of rain soon came, accompanied by the glorious bow of good promise, which presented a vivid contrast with the dark moss covering of the rocky mountains forming the background of the picture. At about 3 p.m. we reached Brewster's Point,[5] the southeastern extreme of Barrow's Peninsula,[6] where we made our fifth encampment.

That night, looking with my spyglass over the snow mountains of Kingaite, I saw what I at first thought to be the fires of a volcano. After consultation with Koojesse and Kooperneung, I concluded it to be the light of the declining moon reflected from the snow. The effect was strikingly peculiar, the light being red, but in form like a comet's tail.

The next day, August 15th, a head wind condemned the boat's crew to a hard pull; and, as they made slow progess, I took my compass and tripod, and walked along the southern coast of Barrow's Peninsula, directing Koojesse to come for me when I should signal him. Charley likewise had gone ahead with his gun to hunt tuktoo. The boat kept close in shore until we came to Hamlen's Bay,[7] which had to be crossed. Here I embarked with Charley, and with a fair breeze we sped across at the rate of about five miles an hour. On the west side of the entrance to this bay were some islands, between which and the main land was a channel; and, in order to get to the northward and westward (which, being the general trend of the coast thus far, I had reason to suppose to be probably its direction to the head of the bay), we must pass through this channel. We should have done so without delay but that the ebb of the tide had left it dry. Not being aware of this, I told Koojesse to go on. With a twinkle in his eye, he said, "Well, you tell 'em so—we try." Accordingly we went on until, rounding an island that was at the mouth of the channel which is called by the Innuits Tin-ne-took-ke-yarn (Low-tide Land), I saw we were on the verge of dry land. A rise and fall of twenty-five feet in the tide made that impassable at low water which six hours before was a deep channel.

Koojesse, on seeing my surprise, looked at me with such a merry laugh that I could not rebuke him had I been so inclined. We turned the boat round, and formed our sixth encampment upon Blanchard's Island.[8]

In the early part of this day, while yet close to Brewster's Point, and while walking on the beach, I met with remains of many Innuit habitations of former days, when they used to build them of earth and stone. Bones of the whale, and of all other animals that principally serve the Innuits for subsistence, lay there in abundance, many of them very old, their age probably numbering hundreds of years. One shoulder-blade of a whale measured five feet along its arc, and four feet radius. Whale-ribs, also, were scattered here and there, one of them being eight feet in length. I also noticed there several graves, but nothing, not even a bone, within them. An old drift oil-cask was also there, sawn in two; one half was standing full of water, the other half was lying down. I gathered up the oak staves and heads for fuel.

Next morning, Friday, August 16th, when I awoke, I found the tide ebbing fast, and it was therefore necessary to get under way at once. In a quarter of an hour we had everything on board, and set out for the desperate work of running the "mill-race" of waters pouring over the rocks, whose tops were then near the surface. If we could not succeed in the attempt, we must either wait until next tide, or make a long detour outward around several islands.

It was an exciting operation. Koojesse stood on the bread-cask that was at the bow of the boat, so that he might indicate the right passage among the rocks. Occasionally we touched some of them, but a motion of the boat-hook in his hand generally led us right. There was a fine breeze helping us, and we also kept our oars at work. Indeed, it required all the power we could muster to carry us along against so fierce a tide. At one time, thump, thump, we came upon the rocks at full speed, fairly arrested in our progress, and experiencing much difficulty in moving forward again. But, favoured by the breeze, we at last got through this channel, and soon stopped at an island to take our much-needed breakfast: That despatched, we again pushed on, keeping along the coast. The land was low, with iron-looking mountains in the background. But some spots showed signs of verdure, and altogether, the day being fine, the scene was charming.

By evening we had arrived at Tongue Cape, on the east side of the entrance to Waddell Bay,[9] and there made our seventh encampment. The whole of the next day was spent by the male Innuits in hunting tuktoo, and by the women in sewing skins and attending to other domestic matters. As usual, I was occupied with my observations.

On Sunday, August 18th, we left our seventh encampment and proceeded along the coast. As we neared Opera-Glass Cape, a point of land on the west side of Waddell Bay, round which we had to pass, a kia was observed approaching; and in a short time, to my great surprise, the old Innuit Artarkparu was alongside of us.

This man was the father of Koojesse's wife, and therefore the meeting was additionally pleasant. He was, as may be recollected, an invalid, having lost the free use of his lower limbs by a disease in his thighs; yet he was rarely idle, every day going out sealing, ducking, or hunting for walrus and

INNUIT SUMMER VILLAGE.

tuktoo. In the winter he moved about by means of sledge and dogs, and no Innuit was ever more patient or more successful than he. Artarkparu had come out from a village not far off, and to that place we directed the boat. We found four tupics erected there, and many familiar faces soon greeted me. Annawa was among them, and also Shevikoo and Esheeloo. The females were busily occupied in sewing skins—some of which were in an offensive condition—for making a kia. A small space was allotted to them for this purpose, and it was particularly interesting to watch their proceedings. The kia covering was hung over a pole resting on the rocks, every thing being kept in a wet state while the women worked, using large braided thread of white-whale sinews. As I stood gazing upon the scene before me, Annawa's big boy was actually standing by his mother and nursing at the breast, she all the time continuing her work, while old Artarkparu hobbled about in the foreground by the aid of a staff in each hand.

Venison and seal-meat were hung to dry on strings stretched along the ridge of each tupic, as shown in the opposite engraving, and provisions were clearly abundant. In the tupic of Artarkparu, Koojesse and Tunukderlien were at home feasting on raw venison, and with them I was invited to partake of the old man's hospitality. Before returning to the boat I also received, as a present, a pocketful of dried tuktoo meat, given me by Annawa.

After a short stay and friendly adieu, we again departed on our way; but just then I thought it possible that old Artarkparu might be able to give me some information. Accordingly I turned back, and, through the aid of Koojesse as interpreter, entered into a conversation with him. We seated ourselves by his side, and the first question I put to him was, Had he ever seen coal, brick, or iron on any of the land near Oopungnewing? He immediately answered in the affirmative. He had seen coal and brick a great many times on an island which he called Niountelik.

He first saw them when he was a boy.

He had also seen heavy pieces of iron on the point of Oopungnewing, next to Niountelik.

"No iron there now, somebody having carried it off."

"Bricks and coals were at Niountelik."

I then asked him, "How many years ago was it when the Innuits first saw these things?"

His reply was, "Am-a-su-ad-lo" (a great, great many). His father, when a boy, had seen them there all the same. Had heard his father often talk about them.

"Some of the pieces of iron were very heavy, so that it was as much as the strongest Innuit could do to lift them."

"Had often made trials of strength, in competition with other Innuits, in lifting. It was quite a practice with the young men to see who was the strongest in lifting the 'heavy stone'" (Innuits so call the iron).

"On the point of another island near by, an oo-mi-ark-chu-a (ship) was once built by kodlunas (white men) a great many, many years ago—so the Innuits of a great many years ago had said."

I took from the boat a little bag which contained some of the coal that I had gathered up with my own hands at Niountelik, and asked him if it was like that he had seen.

He said, "All the same."

I then asked him "where it came from."

His reply was, "He supposed from England, for he had seen the same kind on English whaling vessels in Northumberland Inlet."

This information I obtained from the old man; and I could not help noticing how closely it corresponded with that given to me by Ookijoxy Ninoo some months before.

The whole interview was particularly interesting. I felt as if suddenly taken back into ages that were past; and my heart truly rejoiced as I sat upon the rock and listened to what the old man said of these undoubted Frobisher relics.

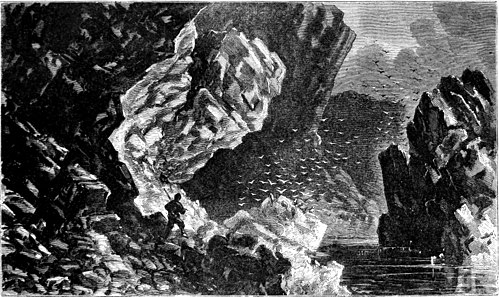

After this interview with Artarkparu, we started at 2.45 p.m. along the coast, closely examining its features, and noting down everything of importance which we saw. The land was bold and high, with much of the iron-rust look about it. Scarcely any vegetation was perceptible. Numerous islands bordered the coast; and, as I looked across the outer waters,

VIEW AT CAPE STEVENS AND WARD'S INLET

it seemed as if a complete chain stretched across the bay to Kingaite.

On reaching the spot which we selected for our eighth encampment—Cape Stevens[10]—I left my crew to unload the boat and erect tupics, while I ascended a mountain that flanked us. On the top I found numerous shells and fossils, some of which I brought away. On descending I took the opposite or north-east side, next a bight that made up into the land. This side of the mountain was almost perpendicular. The winter forces of the North had thrown down to the base a mass of stone, which enabled me to pass upon a kind of causeway to the foot of another mount toward the tupics. There I could not help pausing and glancing around in wondering awe. I cannot put on paper the feelings which struggled within me as I made my way over that debris, and looked above and around me. God built the mountains, and He tumbleth them down again at His will! Overhead was hanging the whole side of a mountain, ready, as it seemed, at any moment, and by the snap of one's finger, to fall! I felt as if obliged to take light and gentle steps. I breathed softly; and, as I looked and looked again, I praised God for all His mighty works.

I ought to say that, on a better view of this mountain, I perceived on its perpendicular side large caverns, with huge projecting rocks hanging directly over them.

I returned to the tupics; and that night, as I lay on my back by our camp-fire, viewing the glorious heavens, I beheld the aurora in all its wondrous beauty. In the vicinity of the moon, where the aurora was dancing and racing to and fro, it was strangely grand. But the most remarkable phenomenon of the kind I ever witnessed was the peculiar movement of the clouds overhead. For some length of time they moved by "hitches," passing with the wind slowly, and then stopping for a few seconds. I called the attention of the Innuits to it, and they noticed this as something they had never seen before. It seemed as if the clouds were battling with an unseen enemy, but that the former had the greater power, and forced their way by steps along the vault above. These clouds were white, and of the kind classified as cumulus. I thought it a very strange matter, and, according to my idea, the aurora had something to do with it.

TUNUKDERLIEN (wife of Koojesse).

- ↑ This cape, at the west entrance to the Countess of Warwick's Sound (of Frobisher), I have named after Mrs. Henry Grinnell. Sarah G.'s Cape is two miles northwest of Oopungnewing, and is in lat. 62° 74′ 30″ N. long. 65° 20′ W.

- ↑ This inlet I name after William Wiswell, of Cincinnati, Ohio. It is on the north side of Frobisher Bay, extending north twelve miles from Oomernung, a small high island on the east side of the entrance of the inlet, in lat. 62° 50½′ N. long. 65° 26′ W.

- ↑ A beautiful sheet of water, mostly surrounded by rugged mountains, and thus named by me after Peter Force, of Washington, D.C. The entrance to his sound is in lat. 62° 55½′ N. long. 65° 48′ W.

- ↑ So named after John D. Jones, of Cincinnati, Ohio. Jones's Cape is in lat. 62° 55′ 30″ N. long. 65° 45′ W.

- ↑ I named this point after A. Brewster, of Norwich, Connecticut. It is on the west side at the entrance to Peter Force Sound, nearly on a parallel with the place of fourth encampment, and is in lat. 62° 55′ N. long. 65° 51′ W.

- ↑ Named by me after John Barrow, of London, England. It is bounded by Newton's Fiord, Peter Force Sound, Frobisher Bay, and Hamlen's Bay. (Vide Chart.)

- ↑ Named after S. L. Hamlen, of Cincinnati, Ohio. This bay runs up almost due north, and is five miles across at its mouth. The centre of its entrance is in lat. 62° 58′ N. long. 66° 10′ W.

- ↑ So named after George S. Blanchard, of Cincinnati, Ohio. Our sixth encampment was in lat. 62° 58′ N and long. 66° 17′ W.

- ↑ Named after William Coventry H. Waddell, of New York City. Its east side (Tongue Cape) is in lat. 63° 11′ 30″, and long. 66° 48′ W.

- ↑ Named by me after John A. Stevens, Jun., of New York City. Cape Stevens is in lat. 63° 21′ N. and long. 67° 10′ W.