Narrative Of The United States Expedition To The River Jordan And The Dead Sea/11

CHAPTER XI.

FROM FORD OF SCKÂ TO PILGRIM’S FORD.

SUNDAY, APRIL 16. A pleasant day-wind light from north-east. We were on the move early this morning. Sherîf was very uneasy about the boats; and yet thought it advisable for him to be with the caravan. He was urgent that the Emir should accompany us on the river. The latter excused himself on the plea of headache.

After a cup of coffee, taken standing, started off with the boats, leaving the caravan to cross over again, and proceed down the right bank.

I found that our Arabs were utterly ignorant of the course of the river, or the nature of its current and its shores. Heretofore, we had been enabled to see the caravan at least once in a day’s journey; but yesterday, from the impossibility of penetrating along the left bank and the high precipitous character of the hills on the right, we saw nothing of them, and our meeting even at night, was, for a long time, very doubtful. The country presented the same appearance as yesterday, except that conglomerate or any kind of rock was rarely seen; but in their stead, banks of semi-indurated clay. The lower plain was evidently narrower and the river often swept alternately against the hills, mostly conical in their shape, and with bold faces, which flank the lower and mark the elevation of the upper plain. These various ramifications of mountain ranges and intervening platforms and valleys afford, according to Humboldt, evidences of ancient volcanic eruptions undergone by the crust of the globe, these having been elevated by matter thrust up in the line of enormous cracks and fissures.

CHANGE IN THE VEGETATION

The vegetation was nearly the same in character, save that it was more luxuriant and of brighter tint on the borders of the stream; more parched and dull on either side beyond it. The oleander increased; there was less of the asphodel, and the acacia was rarely seen, as heretofore, a short distance inland. The tamarisk was more dense and lofty, and the canes were frequently thick and impenetrable. There were many drift-trees in the stream, and bushes and branches were lodged high up in the trees which lined the banks; and much above the latter, conclusive marks of a recent freshet. There were many trees on each side, charred and blackened by fire-caused, doubtless, by the Arabs having burned the dried-up grass to renew their pastures. The ghurrah was also becoming abundant; and we noticed that whenever the soil was dry, the leaves of this tree were most silvery.

SUSPICIOUS NEIGHBOURHOOD

About an hour after starting, we came to the place where Molyneux’s boat was attacked while he was journeying down by land. Stopped to examine. It is just above a very rapid part of the river, where the boat could not have been stopped if the crew had kept her in the stream, unless most of them had been killed by gunshots from the shore. As they all escaped, I concluded that they were surprised when asleep, or loitering on their way. We here saw tracks of a tiger, and of other wild beasts which we could not identify. In many places the trees were drooping to the water’s edge, and the channel sometimes swept us under the branches, thereby preventing us from carrying our awnings; in consequence of which, we suffered more than heretofore from exposure to the sun. At 8:30, there were Arabs in sight on a high hill, and we heard others in the swamp; apprehending a stratagem, we laid on the oars and stood by our arms; but we were not molested.

At 9:30, saw again tracks of wild animals on shore. At 10:38, we struck upon a snag, the current very strong. At 11:20, saw some of our scouts on a hill. 11:40, stopped to take meridian observations. Temperature of the air, 92°; of the water, 72°. At 12:05, started again. At 12:28, Arabs hailed from a high hill on the right, asking whether the horsemen who had passed were friends or enemies. We supposed that they referred to our scouts. At 1 P.M., again saw tracks of wild animals upon the shore; also a great many wild pigeons, some of them very large. The banks, hereabouts, were of red clay, resting on white; the last, semi-indurated, and appearing like stone. There were many fissures in the hills and much debris fallen into the stream. At a sudden turn, started up a flock of partridges. At 1:54, we saw a castor-bean plant growing upon the shore; and, shortly after, passed under an overhanging tree, with a bush fifteen feet up in its branches, lodged there by a recent freshet; for it was deciduous, and the green leaves of the early season were upon it. The river must this year have overflowed to the foundations of the second terrace. We saw some drooping lily-plants, long past their flowering.

PREPARATIONS FOR AN ATTACK

At 2:04, the river running between high triangular hills, we struck in descending a rapid; clothes, notebook, and papers, thoroughly wet, but the boats uninjured.

At 2:27, came in sight of the encampment, the tents, as heretofore, already pitched; — the camping-place, Mukutta Damieh (Ford of Damieh), where the road from Nabulus to Salt crosses the river.

We made but a short day’s journey, in consequence of there not being another place where the boats and caravan could meet between this and the bathing-place of the Christian pilgrims.

Soon after our arrival, both Sherîf and Akil, calling me aside, expressed their belief that the Emir feigned a headache in the morning from fear of going in the boats. The same idea had occurred to me before, but was dismissed as an ungenerous one. They, however, cited circumstantial but conclusive proof that their suspicion was not unfounded.

In the early part oftheir march to-day, the caravan anticipated a skirmish. A strange Arab, supposed to belong to a marauding party, was seen in the distance. The line was closed and the scouts came in, all but a few that were sent to reconnoitre a deep ravine in front. Although but one man was seen, it was suspected that many were concealed in the ravine; for directly opposite was a large encampment of black tents.

Our Bedouin felt or feigned a conviction that an engagement would take place, and all due preparations were immediately made. The camels were halted, and the horsemen, collecting in front, waited for the reconnoitering scouts to return. In the mean time, our Arabs went through their feats of horsemanship, singing their war song, and seemed to be endeavouring to work themselves into a state of phrensy. At their solicitation, Lieut. Dale laid aside his hat and put on a tarbouch and koofeeyeh. Guns were unslung and freshly capped, and swords were loosened in their scabbards.

At a signal from one of the returning scouts, the word was given to advance. With the rest, Mr. Bedlow spurred his horse to urge him forward; but, less valorous or more discreet than his rider, the more he was spurred the farther he backed from the scene of anticipated conflict.

The other party kept aloof, proving neither hostile nor friendly, and ’Akil, as he passed, contemptuously blew his nose at them. They were believed to belong to the tribe El Bely or El Mikhhil Meshakah, whose territories were hereabouts. Doubtless, they were the same who hailed us, to know whether the horsemen who had passed were friends or enemies.

AN OLD ROMAN BRIDGE

After dinner, some of the party crossed the river to examine the ruins of a bridge, seen by the land party from the upper terrace, just before descending to the river. They had to force their way through a tangled thicket, and found a Roman bridge spanning a dry bed, once, perhaps, the main channel of the Jordan, now diverted in its course.

The bridge was of Roman construction, with one arch entire, except a longitudinal fissure on the top, and the ruins of two others, one of them at right angles with the main arch, probably for a mill-sluice. The span of the main arch was fifteen feet; the height, from the bed of the stream to the keystone, twenty feet. From an elevation, the party could see, towards the east, three or four miles distant from them, a line of verdure indicating a water-course. The Arabs say that it is the Zerka (Jabok), which, on the maps, flows into the Jordan very near this place. It approaches quite close, and then pursues a parallel course with the Jordan. To-morrow, we shall probably determine the exact point of junction. To the best of our knowledge, this bridge has never before been described by travelers.

AN ARAB BAKE-OVEN

We were amused this evening at witnessing an Arab kitchen in full operation. The burning embers of a watch-fire were scraped aside, and the heated ground scooped in a hollow to the depth of six or eight inches, and about two feet in diameter. Within this hole was laid, with scrupulous exactness of fit and accommodation to its concave surface, a mass of half-kneaded dough, made of flour and water. The coals were again raked over it, and the fire replenished. A huge pot of rice was then placed upon the fire, into which, from time to time, a quantity of liquid butter was poured, and the compound stirred with a stout branch of a tree, not entirely denuded of its leaves. When the mess was sufficiently cooked, the pot was removed from the fire, the coals again withdrawn, and the bread taken from its primitive oven. Besmeared with dirt and ashes, and dotted with cinders, it bore few evidences of being an article of food. In consistency, as well as in outward appearance, it resembled a long-used blacksmith’s apron, rounded off at the corners.

The whole party gathered round the pot in the open air, and each one tearing off a portion of the leather-bread, worked it into a scoop or spoon, and, dipping pell-mell into the pilau, made a voracious meal, treating the spoons as the Argonauts served their tables, eating them for dessert. With a wash in the Jordan, they were immediately after ready for sleep, and in half an hour were as motionless as the heaps of baggage around them.

MORE BARRENNESS

MONDAY, APRIL 17. At an early hour, Mustafa, shivering and yawning, was moving about in preparation of the morning meal. Long before the sun had risen over the mountains of Gilead, the whole encampment was astir, and all was haste, for there was a long day’s work before us. Although the air was damp and chilly, we knew, from past experience, that before noon the sun would blaze upon us with a power sufficient to carbonize those who should be unprotected from its fierceness. Moreover, from the plateau behind our camp, we could see nothing towards the south but rough and barren cliffs, sweeping into the purple haze of the lower Ghor. And the rolling sand-hills, which form the surface of the upper plain, stretched far along the bases of the mountains without a mark of cultivation, or the shelter of a tree. Heretofore, we had seen patches of grain, but there were none now visible, and all before us was the bleakness of desolation.

The banks of the river, too, were less verdant, except immediately upon the margin, and the vegetation was mostly confined to the ghurrah, the tamarisk, and the cane; the oleander and the asphodel no longer fringed the margin, and the acacia was nowhere seen upon the bordering fields.

As soon as we were up, I sent for the Emir, the Sherîf, and ’Akil, and, in presence of the two last, told the first that, as we were not now in his territory, we no longer required his presence. I then paid him for the services of the guides he had furnished, and for the extra assistance they had rendered in getting the boats down the rapids. As he had declined going in the boats yesterday, when his presence might have been important, I refused to give him anything more than the aba and koofeeyeh he had before received. ’Akil accompanied him to the top of the hill, where they both alighted, and, in the sight of the camp, embraced each other.

With a bite and a sop from Mustafa’s frying pan, we were off at 6:25 A.M. The river, forty yards wide and seven feet deep, was flowing at the rate of six knots down a rapid descent, with much drift-wood in the stream.

We soon passed two large islands, and at 6:57, saw tracks of wild beasts on the shore.

FLOATING TREES

Many large trees were floating down, and a number were lodged against the banks, some of them recently uprooted, for they had their green leaves upon them, and, as on yesterday, there were some small ones lodged high up in the branches of the overhanging trees. The banks were all alluvion, and we began to see the cane in blossom. Altogether, the vegetation was more tropical than heretofore. At 9 A.M., quite warm. Many birds were singing about the banks and under cover of the foliage, but we saw few of them; now and then some pigeons, doves, and cranes, and occasionally a bulbul.

At 10:04, stopped to examine a hill, and collected specimens of semi-indurated clay, coated with efflorescence of lime. The bases of the ridges on each side presented little evidences of vegetation or fertility of soil, notwithstanding their proximity to the river. A few scrubby bushes were scattered here and there, exhibiting the utter sterility of the country through which we were journeying. Fields of thistles and briars occasionally varied the scene; and their sharp projecting thorns bore the motto of the Gael, “Nemo me impune lacessit"

The hills which bounded the valley were immense masses of silicious conglomerate, which, with occasional limestone, extended as far as the eye could reach, showing the geological formation of the Ghor from Lake Tiberias to the Dead Sea, where the limestone is said to preponderate.

SALINE INCRUSTATION

High up in the faces of these hills were immense caverns and excavations, whether natural or artificial we could not tell. The mouths of these caves were blackened, as if by smoke. They may be the haunts of predatory robbers. At 11:40, stopped for meridian observation, near a huge conglomerate rock.

At 1:20, came to the River Jabok (Zerka), flowing in from E.N.E., a small stream trickling down a deep and wide torrent bed. Stopped to examine it. The water was sweet, but the stones upon the bare exposed bank were coated with salt. There was another bed, then dry, showing that in times of freshet there were two outlets to this tributary, which is incorrectly placed upon the maps. There was much of the ghurrah, which seems to delight in a dry soil and a saline atmosphere. The efflorescence on the stones, and on the leaves of the ghurrah, must be a deposition of the atmosphere, when the wind blows from the Dead Sea, about twenty miles distant, in a direct line.

It was here that Jacob wrestled with the angel, at whose touch the sinew of his thigh shrunk up. In commemoration of that event, the Jews, to this day, carefully exclude that sinew from animals they kill for food. This river, too, marks the northern boundary of the land of the Ammonites.

At 1:30, started again, and soon after saw a wild boar swimming across the river. Gave chase, but he escaped us. At 4:32, passed a dry torrent-bed on the right, probably the Wady el Hammam, which separated the lands of the tribe of Manasses from those of the tribe of Ephraim. Still opposite to us was the land of the tribe of Gad. On that side, about twenty miles distant, was Amman, Rabbath Ammon, the capital of the Ammonites. The country of Amnion derived its name from Ben-ammi, the son of Lot.

AN ARAB PRESENT

At 4:52, we passed down wild and dangerous rapids, sweeping along the base of a lofty, perpendicular hill. At 5:14, a small stream on the left: stopped to examine it; found the water clear and sweet; temperature, 76°.

At 5:40, heard and soon after caught glimpses of an Arab in the bushes on the left; at the same time a number of Arabs were calling loudly to us from a hill on the right. Stopped for the other boat to close in, and prepared for a skirmish; at this moment there was a shot from above, and concluding that the other boat had been fired upon, I directed the men to shoot the first objects they saw in the bushes. Fortunately the man we had first seen had now become alarmed and concealed himself; and immediately after, the Fanny Skinner hove in sight, having stopped a moment to fire at a bird. The man in the bushes proved to be a messenger sent by the Arabs on the hill to show us the place of rendezvous for the night. They had been spoken by the caravan as it passed; and their messenger, instead of selecting a conspicuous place on the right bank, had crossed over, and was floundering through the thicket when we came upon him.

This Arab was sent by the sheikh of Huteim, a tribe near Jericho, and brought from him a present of oranges, and a thin, paste-like cake made in Damascus, of debs (a syrup from grapes), starch, and an aromatic seed, I think the sesame. The oranges were peculiarly grateful after the heat and fatigue of the day. The cake was very good if you were very hungry, and, like the trainioness’s lemonade, excellent, if you made-believe very hard.

A NIGHT VOYAGE

The sun went down and night gradually closed in upon us, and the rush of the river seemed more impetuous as the light decreased. We twice passed down rapids, taking care each time to hug the boldest shore. Besides the transition from light to darkness, we had exchanged a heated and stifling for a chilly atmosphere; and while the men, more fortunate, kept their blood in circulation by pulling gently with the oars, the sitters in the stern-sheets fairly shivered with the cold.

There had been such a break-down in the bed of the stream since we passed the Jabok, and such evident indications of volcanic formation, that we became exceedingly anxious. In the obscure gloom we seemed to be stationary and the shores to be flitting by us. With its tumultuous rush the river hurried us onward, and we knew not what the next moment would bring forth-whether it would dash us upon a rock or plunge us down a cataract. The friendly Arab, although he knew the fords and best camping-places on the river, in his own district, was, like all the rest we had met, wholly unacquainted with the stream at all other points.

Under other circumstances it doubtless would have been prudent to lie by until morning; but we were all wet, had neither food nor change of clothing, and apart from danger of attack in a neighbourhood represented as peculiarly bad, sickness would have been the inevitable consequence of a night spent in hunger, cold and watchfulness.

At 9:30 P.M. we arrived at El Meshra, the bathing place of the Christian pilgrims, after having been fifteen hours in the boats. This ford is consecrated by tradition as the place where the Israelites passed over with the ark of the covenant; and where our blessed Saviour was baptized by John. Feeling that it would be desecration to moor the boats at a place so sacred, we passed it, and with some difficulty found a landing below.

A SACRED SPOT

My first act was to bathe in the consecrated stream, thanking God, first, for the precious favour of being permitted to visit such a spot; and secondly for his protecting care throughout our perilous passage. For a long time after, I sat upon the bank, my mind oppressed with awe, as I mused upon the great and wondrous events which had here occurred. Perhaps directly before me, for this is near Jericho, “the waters stood and rose up upon an heap,” and the multitudinous host of the Israelites passed over, — and in the bed of the stream, a few yards distant, may be the twelve stones, marking “the place where the feet of the priests which bare the ark of the covenant stood.”

Tradition, sustained by the geographical features of the country, makes this also the scene of the baptism of the Redeemer. The mind of man, trammelled by sin, cannot soar in contemplation of so sublime an event. On that wondrous day, when the Deity veiled in flesh descended the bank, all nature, hushed in awe, looked on, — and the impetuous river, in grateful homage, must have stayed its course, and gently laved the body of its Lord.

In such a place, it seemed almost desecration to permit the mind to be diverted by the cares which pressed upon it — but it was wrong — for next to faith, surely the highest Christian obligation is the performance of duty.

Over against this was no doubt the Bethabara of the New Testament, whither the Saviour retired when the Jews sought to take him at the feast of the dedication. The interpretation of Bethabara, is “a place of passage over.” Our Lord repaired to Bethabara, where John was baptizing; and as the ford probably derived its name from the passage of the Israelites with the ark of the covenant, the inference is not unreasonable that this spot has been doubly hallowed.

CAPTURE OF A CAMEL

In ten minutes after leaving the camping-ground this morning, the caravan struck upon the plain and crossed the wady Faria, pursuing a S. by W. course. Across the ravine, they saw a young camel browsing among the brown fringe and stunted bushes, which, in these plains, serve to protect the scanty vegetation from the intense heat of the sun. This creature had evidently strayed from some fellahin encampment, or had been abandoned by its owners when pursued by the Bedouin, many of whom they had seen the day previous on the eastern side of the Jordan. The camel being quite wild, racked off at full speed on their approach, and the scouts immediately started in pursuit. Its motion in running, although awkward, was exceedingly rapid; dashing ahead at a long and stretching pace, and outstripping most of the horses in pursuit. Its whole body swayed regularly with its peculiar racking motion, as before remarked, exactly like the yawing of a ship before the wind. Whether it walks or runs, the camel ever throws forward its hind and fore leg on the same side and at the same time, as a horse does in pacing. The fugitive was soon caught, and, true to its early teaching, knelt down the moment a hand was placed upon its neck. ’Akil, abandoning his mare, mounted the prize, and, without bridle or halter, dashed off at full speed over the plain to increase the number of our beasts of burden. The high peak of “Kurn Surtabeh,” “horn of the rhinoceros,” bore W. ¼ N. from this point of their progress.

Thence, keeping along the chalky plain at the base of the western hills, they crossed a low ridge of sand, running E. by S., upon which they discovered two upright stones, marking a burial-place, called by the Arabs “Gubboor.”

At 9:30, they crossed Wady el Aujeh, and pursued a southerly course; the faces of the mountains broken here and there with dark precipices, which gradually assumed a dark brown and reddish hue, with occasional strata resembling red sandstone.

GAZELLES

Beyond Wady el Aujeh, the soil bore a scanty crop of grass, now much parched; and to the right, where the mountains receded from the plain, there were extensive fields of low, scrubby bushes, powdered with the clay-dust of the soil; on the left, was a blank desert, with one or two oases, and a waving line of green, where the Jordan betrayed itself, at times, by a glitter like the sheen from bright metal.

It was now mid-day, and the heat and blinding light of the sun were almost insupportable: they were obliged to stop to rest the wearied caravan, the Arabs making a tent of their abas, supported on spears.

At 1 P.M., they were again in motion, and, passing through a field of wild mustard, came to an open space, nothing but sand and rocks — a perfect desert — where were traces of a broad-paved road, which they believed to be Roman.

At 3 P.M., for the first time, they saw some gazelles, and gave chase to them. At a low, whistling noise made by one of the Arabs, the affrighted creatures stopped, and looked earnestly towards them; but, owing to an incautious movement, they took to flight, and went bounding over the hills beyond the possibility of pursuit.

Crossing Wady el Abyad, they passed through a grove of nubk and wild olive, and came upon a ruined village. Shortly after, they stopped to water in the Wady Na-wa-’imeh, with a shallow stream of clear, sweet water. Thence leaving the Quarantania (reported to be the mountain of our Saviour’s fasting and temptation) on the right, and passing east of the fountain healed by Elisha, and of Jericho, they came to Ain el Hadj (Pilgrim’s fountain), in the plain of Gilgal. Here they were joined by a few Riha (Jericho) Arabs, all having long-barrelled guns, with extraordinary crooked ram’s-horn powder-flasks, perhaps modelled after the horns employed by the Israelites in toppling down the walls of Jericho. Of this city, the first conquest of the Israelites west of the Jordan, and where Herod the Great died, but a solitary tower remains (if, indeed, it be the true site). How truly has the curse of Joshua respecting it been fulfilled!

A GLIMPSE OF THE DEAD SEA

Here the wilderness blossomed as the rose. A broad tract was covered with the olive, the nubk, and many shrubs and flowers. From it they had the first view of the Dead Sea, and the grim mountains of Moab to the south-east. There were few evidences of volcanic agency visible, but the calcined and desolate aspect indicated the theatre of a fierce conflagration; — the cliffs, of the hue of ashes, looking as if they had been riven by thunderbolts, and scathed by lightning.

Pursuing a. south-easterly course, they passed a broad tract of argillaceous soil, rising in fantastic hills, among which they started a coney from its form.

At 5 P.M., they came upon the banks of the river, excessively wearied, having been eleven hours in the saddle.

The tents had been pitched by the land-party before we arrived, directly on the bank down which the pilgrims would, early in the morning, descend to the river. Lieut. Dale had objected to pitching them on this spot, but our Arabs assured him that the pilgrims would not arrive until late to-morrow. The night was already far advanced, and the men were so weary, that I thought it best to postpone moving the tents until the morning.

After a slight and hurried supper, we stationed sentries, and threw ourselves, exhausted, upon the lap of mother earth, with the tent as our covering, and whatever we could find for pillows.

During the night there was an alarm. We sprang from the tents at the report of a gun, and found our Arab scouts on the right hailing someone on the opposite bank; upon whom, contrary to all military usage, they had previously fired. It proved to be a fellah, attempting to cross the ford, which was too deep.

The alarm, although a false one, had the good effect of showing that all were upon the alert. At this time, it is said, there are always a great many Arabs prowling about, to cut off pilgrims straying from the strong military escort which accompanies them from Jerusalem, under the command of the Pasha, or an officer of high rank.

We have, to-day, according to ’Akil, passed through the territory of the Beni Adwans and Beni Sukr’s, and into those of the wandering tribes of the lower Ghor. On the opposite side is “the valley over against Beth-peor,” where the Israelites dwelt before they crossed the Jordan.

In the descent of the Jordan, we have, at every encampment, determined its astronomical position, and its relative level with the Mediterranean; and have, throughout, sketched the topography of the river and the valley. The many windings of the river, and its numerous rapids, will account for the difference of level between lake Tiberias and the Dead Sea.

AN ARMY OF PILGRIMS

TUESDAY, APRIL 18. At 3 A.M., we were aroused by the intelligence that the pilgrims were coming. Rising in haste, we beheld thousands of torchlights, with a dark mass beneath, moving rapidly over the hills.

Striking our tents with precipitation, we hurriedly removed them and all our effects a short distance to the left. We had scarce finished, when they were upon us: — men, women, and children, mounted on camels, horses, mules; and donkeys, rushed impetuously by toward the bank. They presented the appearance of fugitives from a routed army. Our Bedouin friends here stood us in good stead, sticking their tufted spears before our tents, they mounted their steeds and formed a military cordon round us. But for them we should have been run down, and most of our effects trampled upon, scattered and lost.

A HETEROGENEOUS MULTITUDE

Strange that we should have been shielded from a Christian throng by wild children of the desert — Muslims in name, but pagans in reality. Nothing but the spears and swarthy faces of the Arabs saved us.

I had, in the meantime, sent the boats to the opposite shore, a little below the bathing-place, as well to be out of the way as to be in readiness to render assistance, should any of the crowd be swept down by the current, and in danger of drowning.

While the boats were taking their position, one of the earlier bathers cried out that it was a sacred place; but when the purpose was explained to him, he warmly thanked us. Moored to the opposite shore, with their crews in them, they presented an unusual spectacle. The party which had disturbed us was the advanced guard of the great body of the pilgrims. At 5, just at the dawn of day, the last made its appearance, coming over the crest of a high ridge, in one tumultuous and eager throng.

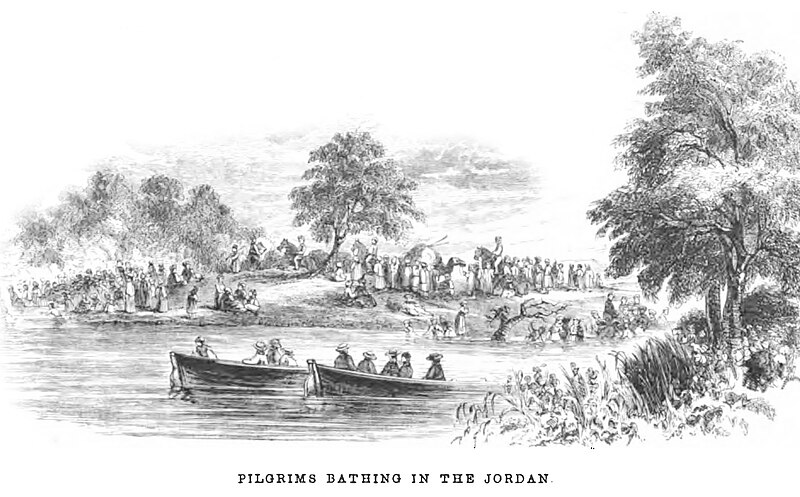

In all the wild haste of a disorderly rout, Copts and Russians, Poles, Armenians, Greeks and Syrians, from all parts of Asia, from Europe, from Africa and from far distant America, on they came; men, women and children, of every age and hue, and in every variety of costume; talking, screaming, shouting, in almost every known language under the sun.

Mounted as variously as those who had preceded them, many of the women and children were suspended in baskets or confined in cages; and, with their eyes scaravan ed towards the river, heedless of all intervening obstacles, they hurried eagerly forward, and dismounting in haste, and disrobing with precipitation, rushed down the bank and threw themselves into the stream.

BATHING IN JORDAN

They seemed to be absorbed by one impulsive feeling, and perfectly regardless of the observations of others. Each one plunged himself, or was dipped by another, three times, below the surface, in honour of the Trinity; and then filled a bottle, or some other utensil, from the river.

The bathing-dress of many of the pilgrims was a white gown with a black cross upon it. Most of them, as soon as they dressed, cut branches either of the agnus castus, or willow; and, dipping them in the consecrated stream, bore them away as memorials of their visit.

In an hour, they began to disappear; and in less than three hours the trodden surface of the lately crowded bank reflected no human shadow. The pageant disappeared as rapidly as it had approached, and left to us once more the silence and the solitude of the wilderness. It was like a dream. An immense crowd of human beings, said to be 8000, but I thought not so many, had passed and repassed before our tents and left not a vestige behind them.

Everyone bathed, a few Franks excepted; the greater number, in a quiet and reverential manner; but some, I am sorry to say, displayed an ill-timed levity.

Besides a party of English, a lady among them, and three French naval officers, we were gladdened by meeting two of our countrymen, who were gratified in their turn at seeing the stars and stripes floating above the consecrated river, and the boats which bore them ready to rescue, if necessary, a drowning pilgrim.

We were in the land of Benjamin; opposite was that of Reuben, which was in the country of the Ammonites, and on the plain of Moab.

A short distance from us was Jericho, the walls of which fell at the sound of trumpets; and fourteen miles on the other side was Heshbon, where Sihon the king of the Amorites dwelt.

Upon this bank are a few plane trees and many willow and tamarisk, with some of the agnus castus. Within the bank and about the plain are scattered the acacia, the nubk (spina Christi), and the mala insana, or mad apple. On the opposite side are acacia, tamarisk, willow, and a thicket of canes lower down. The pilgrims descended to the river where the bank gradually slopes. Above and below it is precipitous. The banks must have been always high in places, and the water deep; or the axe-head would not have fallen into the water, and Elisha’s miracle been unnecessary to recover it.

Shortly after the departure of the pilgrims, a heavy cloud settled above the western hills, and we had sharp lightning and loud thunder, followed by a refreshing shower of rain.

FRESH PROVISIONS NEEDED

We were all much wearied, and in consequence of living upon salt food since we left Tiberias, were much in need of refreshment. Disappointed in procuring fresh provisions from Jericho, we determined to proceed at once to the Dead Sea, only a few hours distant.

Dr. Anderson volunteered to go to Jerusalem to superintend the transportation of the bread I had sent there; and I gladly accepted his services, instructing him to make a geological reconnoissance of his route.

REPORT TO THE DEPARTMENT

Before starting, I made the following report to the Secretary of the Navy.

“Meshra’a, on the Jordan, near Jericho,

APRIL 18, 1848:

“SIR: — I have the honour to report our safe arrival at this place, within a few miles of the Dead Sea. While at Tiberias, I purchased for 500 piastres ($21.25), a frame boat to assist in conveying our things and save expense of transportation. With a large and beautiful lake before them, filled with fish and abounding with wild fowl, the misgoverned and listless inhabitants had but the solitary boat I purchased, used only to bring wood across from the opposite side. On the 10th, at 2 P.M., we started, and, proceeding to the foot of the lake, commenced our descent of the Jordan. Notwithstanding the most diligent inquiry, I could procure no information to be relied on, respecting the river, in Tiberias.

“To my consternation, I soon found that the Jordan was interrupted in its course by frequent and most fearful rapids. Determined, however, to persevere, I was cordially supported by every one under my command. We had to clear out old channels, to make new ones, and sometimes, placing our sole trust in Providence, plunged with headlong velocity down appalling descents. So great were the difficulties, that on the second evening we were in a direct line but twelve miles distant from Tiberias. On the third morning I was obliged to abandon the frame boat from her shattered condition. No other kind of boats in the world than such as we have, combining great strength with buoyancy, could have sustained the shocks they encountered. As the passage by the river was considered the most perilous, alike from the dangers of its channel and the liability to an attack, I felt it my duty, as I have before advised you, to undertake it in person. With the Fanny Mason I took the lead, and Passed Midshipman Aulick followed in the Fanny Skinner. This young officer has throughout evinced so much coolness and discretion, in the most trying situations, as to win my warmest approbation, and I soon felt sure that I had one behind me who would follow whithersoever I might lead. I am happy to say that the boats, although. severely bruised, are not materially injured, and in a few hours hope to repair all damages.

“We reached here last night after dark, having made about fifty miles since sunrise; and I have stopped here, in part, for the purpose mentioned above, and partly to rescue any of the pilgrims who might be in danger of drowning accidents, it is said, occurring every year. This morning, before daylight, they began to arrive, and by five o’clock, there were several thousands on the bank. The boats were moored on the opposite side, where they were out of the way, and yet convenient to render assistance, should it unfortunately be required. I am happy to say that nothing occurred, and the pilgrims have all departed.

“The great secret of the depression between Lake Tiberias and the Dead Sea, is solved by the tortuous course of the Jordan. In a space of sixty miles of latitude and four or five miles of longitude, the Jordan traverses at least 200 miles. The river is in the latter stage of a freshet-a few weeks earlier or later, and passage would have been impracticable. As it is, we have plunged down twenty-seven threatening rapids, besides a great many of lesser magnitude.

“As soon as leisure permits, I will send you a topographical sketch of the river, when you will perceive that its course is more sinuous even than that of the Mississippi.

Although the party has been very much exposed, those in the boats especially, from being constantly wet, we are perfectly well. Until I hear from you on the subject, however, I deem it my duty to retain Dr. Anderson, whose medical or surgical assistance may at any moment be required.

“We have met with no interruption from the Arabs, although we were twice called upon to stand to our arms. Our Bedouin allies have proved efficient and faithful.

“I am, very respectfully, &c.,

“W. F. LYNCH, LT. U. S. N.

“HON. J. Y. MASON,

“Secretary of the Navy.

ENTER THE DEAD SEA

At 3:25, passed by the extreme western point, where the river is 180 yards wide and three feet deep, and entered upon the Dead Sea; the water, a nauseous compound of bitters and salts.

The river, where it enters the sea, is inclined towards the eastern shore, very much as is represented on the map of Messrs. Robinson and Smith, which is the most exact of any we have seen. There is a considerable bay between the river and the mountains of Belka, in Ammon, on the eastern shore of the sea.

A fresh north-west wind was blowing as we rounded the point. We endeavoured to steer a little to the north of west, to make a true west course, and threw the patent log overboard to measure the distance; but the wind rose so rapidly that the boats could not keep head to wind, and we were obliged to haul the log in. The sea continued to rise with the increasing wind, which gradually freshened to a gale, and presented an agitated surface of foaming brine; the spray, evaporating as it fell, left incrustations of salt upon our clothes, our hands and faces; and while it conveyed a prickly sensation wherever it touched the skin, was, above all, exceedingly painful to the eyes. The boats, heavily, laden, struggled sluggishly at first; but when the wind freshened in its fierceness, from the density of the water, it seemed as if their bows were encountering the sledge-hammers of the Titans, instead of the opposing waves of an angry sea. At 3:50, passed apiece of drift-wood, and soon after saw three swallows and a gull.

At 4:55, the wind blew so fiercely that the boats could make no headway; not even the Fanny Skinner, which was nearer to the weather shore, and we drifted rapidly to leeward: threw over some of the fresh water, to lighten the Fanny Mason, which laboured very much, and I began to fear that both boats would founder.