the melody remains intact. The following is a list of the most characteristic turns and 'grace-notes' used in Hungarian music, given by the writer above mentioned:

![{ \override Score.TimeSignature #'stencil = ##f \cadenzaOn \relative g'' {

s8^"(1)" \grace a16 g8-. fis16[ a] g8-. r8 \bar "||"

r^"(2)" d-.\prall\( cis-. d-.\) \bar "||"

d,[^"(3)"\( cis16 d] e[ d cis d]\) \bar "||"

s8^"(4)" \appoggiatura { c'16[ d e] } f8-. e-. d4 \bar "||"

d16[(^"(5)" c]) b[( d)] c8-. r \bar "||"

g8[^"(6)" \times 2/3 { g16 a g] } fis8-.[ g-.] \bar "||"

s8^"(7)" \appoggiatura { b16[ c d] } c8-. \bar "||"

s8^"(8)" a32[( g]) r16 g4-> r8 \bar "||"

c4^"(9)" \times 4/5 { d16[ e d c d] } \bar "|" e4 \bar "||"

s8^"(10)" d8 r c\prall r \bar "|" b\prall r a\prall r \bar "||" } }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/6/q/6qud0q4iejvqn2d213ubiavp766kbvn/6qud0q4i.png)

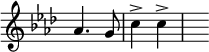

and the double cadence

to which may be added

![{ \override Score.TimeSignature #'stencil = ##f \cadenzaOn \relative c'' {

s8^"(13)" \acciaccatura d8 c8-.[ c16( d)] c8-. \bar "||"

s8^"(14)" \times 4/5 { b16[ a gis a b] } a4 \bar "||" } }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/k/3/k39iqib8eqgwi500nq65f957dn4wx8h/k39iqib8.png)

The charm which these 'agrémens' give is well illustrated by the first two bars of Schubert's 'Moment musical,' in F minor, where the phrase

![{ \override Score.TimeSignature #'stencil = ##f \time 2/4 \key f \minor \relative a' { \acciaccatura bes16 aes8-. aes16( bes) aes8-. g | \appoggiatura { aes16[ bes] } <aes c>4-> \appoggiatura { aes16[ bes] } <aes c>4-> | s } }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/g/4/g4xujdebbb6i0qol4zq85i6o6y0d6fy/g4xujdeb.png)

is seen to be compounded of the comparatively uninteresting phrase

together with No. 13 and part of No. 4 of the above embellishments.

But the importance of Hungarian music lies not so much in its intrinsic beauty or interest, as in the use made of it by the great classical masters, and the influence which it exercises on their works. The first composer of note who embodies the Hungarian peculiarities is Haydn. The most obvious instance of course is the well-known 'Rondo all' Ongarese,' or 'Gipsy Rondo,' in the Trio No. 1 in G major; but besides this avowedly Hungarian composition there are many passages in his works which show that the years during which he held the post of conductor of Prince Esterhazy's private (and almost entirely Hungarian) band, were not without their effect. Instances of this may be found in many of the 'Salomon symphonies' (the Symphony in B♭, No. 9), etc. We next come to Beethoven, in whom the Hungarian element appears but rarely. In the music to 'King Stephen,' however, it is prominent, as we might expect, in many parts, and the chorus 'Wo die Unschuld Blumen streute' is marked 'Andante con moto all' Ongarese.' The composer however who has made the greatest use of Hungarian characteristics is Schubert. Constantly throughout his works we come upon a peculiarity which at once tells us of its nationality. The C major Symphony (No. 9) for instance, or the Fantasia in C major, op. 15, are full of Hungarian feeling and character, while almost all the peculiarities of the Hungarian style are present in the little 'Moment musical' before alluded to, and still more in the splendid Divertissement à la hongroise (op. 54).

Never, probably, has Hungarian music had such an influence over compositions as at the present time, and among living composers. It is enough to cite such names as Liszt, Brahms, and Joachim, to bring to the mind of every reader the use made by each of them of Hungarian forms and themes. We may think it only natural that the first and the last of these should, being natives of Hungary, have a natural love for their national music, as we see in the 'Legend of St. Elizabeth,' the symphonic poem 'Hungaria,' the fourteen 'Rhapsodies Hongroises,' by Liszt, and the noble Hungarian violin concerto of Joachim, which is a splendid instance of the combination of national characteristics with the classical forms. In the case of Brahms, however, there is no national prejudice to which the partiality for the Hungarian element might be ascribed, and yet here we meet with many Magyar characteristics, not only in the Ungarische Tänze, which are nothing more than transcriptions for the piano of the wild performance of the Hungarian bands (according to the best authorities on this subject), but also in the Sextets for strings, the pianoforte variations, etc.

The following are some of the most important Magyar compositions.

Dances.—The Csárdás, derived from Csárdá, an inn on the Puszta (plain), where this dance was first performed. Every Csárdás consists of two movements,—a 'Lassu,' or slow movement, andante maestoso, and a 'Friss,' or 'quickstep,' allegro vivace. These two alternate at the will of the dancers, a sign being given to the musicians when a change is wished. [See Csárdás.]

The 'Kör-táncz,' or Society-Dance, of which a part consists of a Toborzó, or Recruiting dance.

The 'Kanász-táncz,' or Swineherd's Dance, is danced by the lower classes only.

Operas.—Among national Magyar operas—i.e. operas of which the libretti are founded on national historic events, and the music is characterised by Magyar rhythms, etc.—may be mentioned 'Hunyadi László' 'Báthory Maria,' 'Bánk Ban,' and 'Bránkovics,' by Francis Erkel, and the comic opera 'Ilka,' by Doppler. Besides these two composers, the names of Mocsonyi, Császár, Fáy, and Bartha, may be given as examples of operatic writers.

Songs.—Many collections of Nepdal, or popular songs, have been published. One of these, 'Repüli Fecske,' has been made widely known by M. Remenyi's adaptation of it for the violin.

The great National March—The 'Rákocsy Indulo,' made famous by Hector Berlioz, who introduced it in Paris with an immense orchestra.

The National Hymn of Hungary is called 'Százat,' or 'Appeal.'