It is impossible to over-estimate the value of the information contained in this most instructive treatise. The first edition—of which a copy is happily preserved in the Library of the British Museum—is so excessively rare, that, until M. Fétis fortunately discovered an example in the Royal Library at Paris, a reprint, of 1519, was very commonly regarded as the editio princeps. The edition described by Burney, and Hawkins, is a much later one, printed, at Cologne, in 1535. In 1609, our own John Dowland printed a correct though deliciously quaint English translation, in London; and it is through the medium of this that the work is best known in this country. Hawkins, indeed, though he mentions the Latin original, gives all his quotations from Dowland's version.

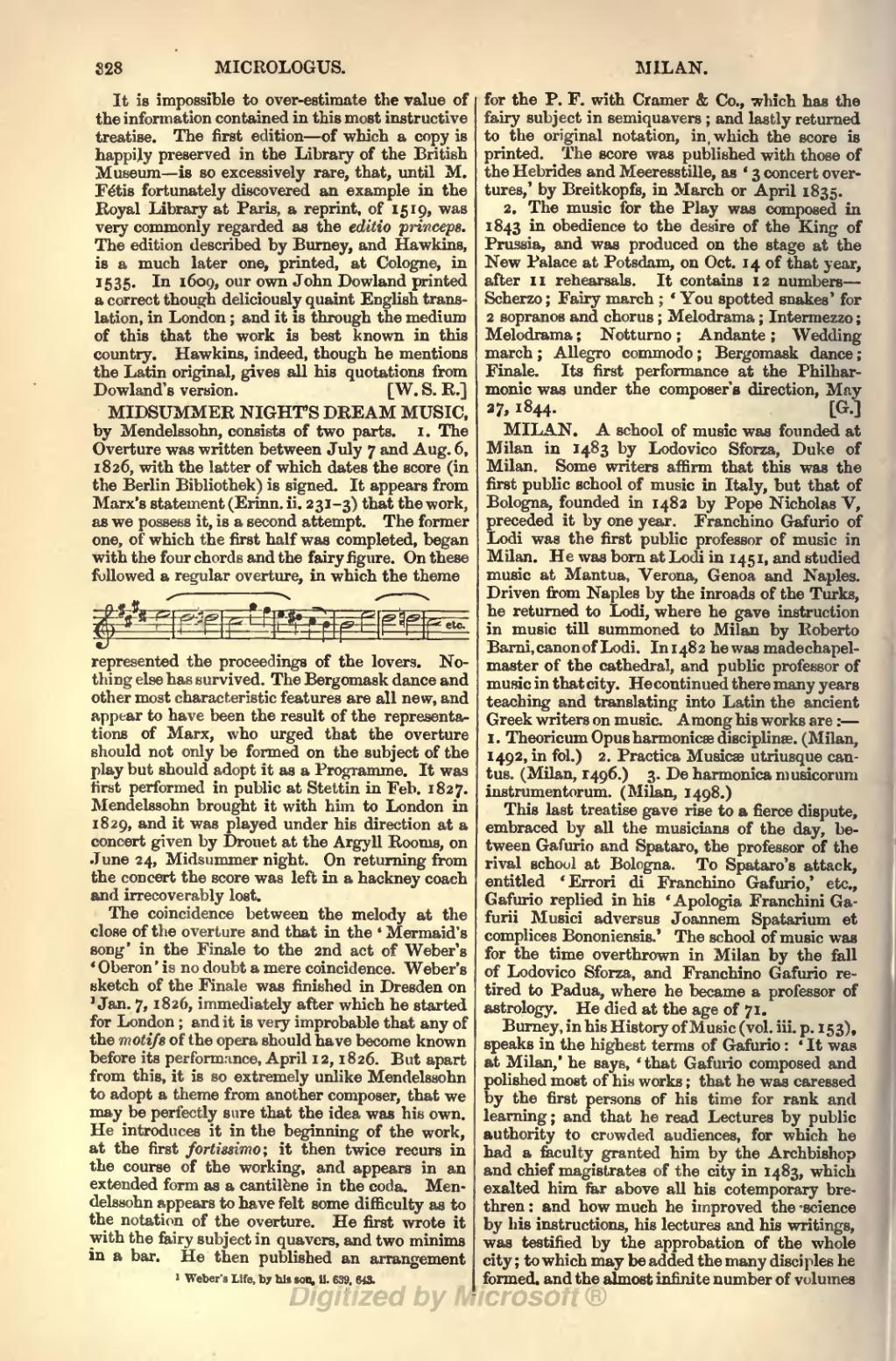

MIDSUMMER NIGHT'S DREAM MUSIC, by Mendelssohn, consists of two parts, 1. The Overture was written between July 7 and Aug. 6, 1826, with the latter of which dates the score (in the Berlin Bibliothek) is signed. It appears from Marx's statement (Erinn. ii. 231–3) that the work, as we possess it, is a second attempt. The former one, of which the first half was completed, began with the four chords and the fairy figure. On these followed a regular overture, in which the theme

etc.

represented the proceedings of the lovers. Nothing else has survived. The Bergomask dance and other most characteristic features are all new, and appear to have been the result of the representations of Marx, who urged that the overture should not only be formed on the subject of the play but should adopt it as a Programme. It was first performed in public at Stettin in Feb. 1827. Mendelssohn brought it with him to London in 1829, and it was played under his direction at a concert given by Drouet at the Argyll Rooms, on June 24, Midsummer night. On returning from the concert the score was left in a hackney coach and irrecoverably lost.

The coincidence between the melody at the close of the overture and that in the 'Mermaid's song' in the Finale to the 2nd act of Weber's 'Oberon' is no doubt a mere coincidence. Weber's sketch of the Finale was finished in Dresden on [1]Jan. 7, 1826, immediately after which he started for London; and it is very improbable that any of the motifs of the opera should have become known before its performance, April 12, 1826. But apart from this, it is so extremely unlike Mendelssohn to adopt a theme from another composer, that we may be perfectly sure that the idea was his own. He introduces it in the beginning of the work, at the first fortissimo; it then twice recurs in the course of the working, and appears in an extended form as a cantilène in the coda. Mendelssohn appears to have felt some difficulty as to the notation of the overture. He first wrote it with the fairy subject in quavers, and two minims in a bar. He then published an arrangement for the P.F. with Cramer & Co., which has the fairy subject in semiquavers; and lastly returned to the original notation, in, which the score is printed. The score was published with those of the Hebrides and Meeresstille, as '3 concert overtures,' by Breitkopfs, in March or April 1835.

2. The music for the Play was composed in 1843 in obedience to the desire of the King of Prussia, and was produced on the stage at the New Palace at Potsdam, on Oct. 14 of that year, after 11 rehearsals. It contains 12 numbers—Scherzo; Fairy march; 'You spotted snakes' for 2 sopranos and chorus; Melodrama; Intermezzo; Melodrama; Notturno; Andante; Wedding march; Allegro commodo; Bergomask dance; Finale. Its first performance at the Philharmonic was under the composer's direction, May 27, 1844.

MILAN. A school of music was founded at Milan in 1483 by Lodovico Sforza, Duke of Milan. Some writers affirm that this was the first public school of music in Italy, but that of Bologna, founded in 1482 by Pope Nicholas V, preceded it by one year. Franchino Gafurio of Lodi was the first public professor of music in Milan. He was born at Lodi in 1451, and studied music at Mantua, Verona, Genoa and Naples. Driven from Naples by the inroads of the Turks, he returned to Lodi, where he gave instruction in music till summoned to Milan by Roberto Barni, canon of Lodi. In 1482 he was made chapelmaster of the cathedral, and public professor of music in that city. He continued there many years teaching and translating into Latin the ancient Greek writers on music. Among his works are:—1. Theoricum Opus harmonicas disciplines. (Milan, 1492, in fol.) 2. Practica Musicæ utriusque cantus. (Milan, 1496.) 3. De harmonica musicorum instrumentorum. (Milan, 1498.)

This last treatise gave rise to a fierce dispute, embraced by all the musicians of the day, between Gafurio and Spataro, the professor of the rival school at Bologna. To Spataro's attack, entitled 'Errori di Franchino Gafurio,' etc., Gafurio replied in his 'Apologia Franchini Gafurii Musici ad versus Joannem Spatarium et complices Bononiensis.' The school of music was for the time overthrown in Milan by the fall of Lodovico Sforza, and Franchino Gafurio retired to Padua, where he became a professor of astrology. He died at the age of 71.

Burney, in his History of Music (vol. iii. p. 153), speaks in the highest terms of Gafurio: 'It was at Milan,' he says, 'that Gafurio composed and polished most of his works; that he was caressed by the first persons of his time for rank and learning; and that he read Lectures by public authority to crowded audiences, for which he had a faculty granted him by the Archbishop and chief magistrates of the city in 1483, which exalted him far above all his cotemporary brethren: and how much he improved the science by his instructions, his lectures and his writings, was testified by the approbation of the whole city; to which may be added the many disciples he formed, and the almost infinite number of volumes

- ↑ Weber's Life, by his son, ii. 639, 643.