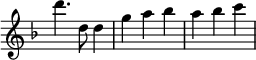

where one odd bar is thrust in to break the continuity, as thus in the Andante of Beethoven's C minor Symphony:

![\relative e' { \key aes \major \time 3/8 \override Score.BarNumber #'break-visibility = #'#(#f #f #f) \partial 8

ees16. g32 | \mark "•" <aes ees c>8 q <bes g ees> |

<c aes>4 <aes ees c>16. <bes g ees>32 | \mark "•"

<c aes>8 q <des bes> | <ees c>4 ees16. f32 | \mark "•"

<< { <ges ees c>4 ees16. f32 | \mark "•" <ges ees c>4 ees16. f32 } \\

{ r8 a,4 | r8 a4 } >>

<aes c ees fis>4.:64 | \mark "•"

<g c e g>16.[ ees32] c8[ <d b g>] | c4 }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/n/u/nup1jrfrsz03ujmaz2ogn85vodv9dqi/nup1jrfr.png)

this may also be effected by causing a fresh phrase to begin with a strong accent on the weak bar with which the previous subject ended, thus really eliding a bar, as for instance in the minuet in Haydn's 'Reine de France' Symphony:

Here the bar marked (a) is the overlapping of two rhythmic periods.

Combinations of two-bar rhythm are the rhythms of four and six bars. The first of these requires no comment, being the most common of existing forms. Beethoven has specially marked in two cases (Scherzo of 9th Symphony, and Scherzo of C♯ minor Quartet) 'Ritmo de 4 battute,' because, these compositions being in such short bars, the rhythm is not readily perceptible. The six-bar rhythm is a most useful combination, as it may consist of four bars followed by two, two by four, three and three, or two, two and two. The well-known minuet by Lulli (from 'Le Bourgeois Gentilhomme') is in the first of these combinations throughout.

And the opening of the Andante of Beethoven's 1st Symphony is another good example. Haydn is especially fond of this rhythm, especially in the two first-named forms. Of the rhythm of thrice two bars a good specimen is afforded by the Scherzo of Schubert's C major Symphony, where, after the two subjects (both in four-bar rhythm) have been announced, the strings in unison mount and descend the scale in accompaniment to a portion of the first theme, thus:

A still better example is the first section of 'God save the Queen.'

This brings us to triple rhythm, uncombined with double.

Three-bar rhythm, if in a slow time, conveys a very uncomfortable lop-sided sensation to the uncultivated ear. The writer remembers an instance when the band could hardly be brought to play a section of an Andante in 9–8 time and rhythm of three bars. The combination of 3 x 3 x 3 was one which their sense of accent refused to acknowledge. Beethoven has taken the trouble in the Scherzo of his 9th Symphony to mark 'Ritmo di tre battute,' although in such quick time it is hardly necessary; the passage,

being understood as though written—

Numerous instances of triple rhythm occur, which he has not troubled to mark; as in the Trio of the C minor Symphony Scherzo:—

Rhythm of five bars is not, as a rule, productive of good effect, and cannot be used—any more than the other unusual rhythms—for long together. It is best when consisting of four bars followed by one, and is most often found in compound form—that is, as eight bars followed by two.

Minuet, Mozart's Symphony in C (No. 6).

A very quaint effect is produced by the unusual rhythm of seven. An impression is conveyed that the eighth bar—a weak one—has got left out through inaccurate sense of rhythm, as so often happens with street-singers and the like. Wagner has taken advantage of this in his 'Tanz der Lehrbuben' ('Die Meistersinger'), thus:—

It is obvious that all larger symmetrical groups than the above need be taken no heed of, as they are reducible to the smaller periods. One more point remains to be noticed, which, a beauty in older and simpler music, is becoming a source of weakness in modern times. This is the disguising or concealing of the rhythm by strong accents or change of harmony in weak bars. The last move-