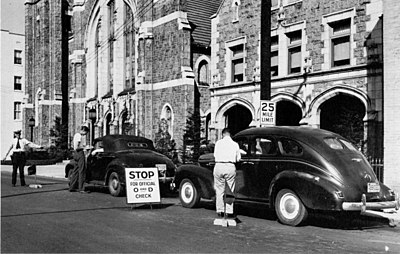

An “origin-and-destination” survey.

Before the war was over, many of the State highway departments became involved with the large cities and urban counties in the planning of costly schemes for expanding highway capacities. Most of the Federal aid provided by Congress for postwar planning went into urban highways.

Federal Aid for Urban Highways

In its early days, the Federal-aid program applied strictly to rural roads, “excluding every street and road in a place having a population, as shown by the latest available Federal census, of two thousand five hundred or more, . . .”[1] This exclusion was suspended in the Emergency Relief and Construction Act of 1932 and the National Industrial Recovery Act of 1933, and abolished altogether in the Hayden-Cartwright Act of 1934. Thereafter, the States enlarged their Federal-aid systems to include extensions of Federal-aid routes into and through municipalities and even new routes wholly within urban areas, but the main interest of the State highway departments was in the rural highway systems outside the cities.

Congress changed all this in 1944 by specifically earmarking $125 million annually for the first 3 post-war years for roads in urban areas. These funds were to be apportioned to the States in the ratio that their urban populations (cities of 5,000 or more inhabitants) bore to the national urban population. In the same Act, Congress established the National System of Interstate Highways and required that its routes should be selected by the States within the cities as well as between them. Thus, the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1944 brought the State highway departments, and also the Public Roads Administration (PRA), actively into the field of city and regional transportation planning beside the city and county officials.[N 1]

- ↑ The Bureau of Public Roads (BPR) had pioneered in urban traffic studies in the Cook County Transportation Survey of 1924, the first comprehensive study of traffic in an urban region including a large city[2] and in the Cleveland Regional Area Traffic Survey of 1927. The latter was the first concerted study by all levels of government of the traffic problems of a single metropolitan region.[3]

Urban Traffic Studies

Before they could designate the urban Interstate System arteries with confidence, the planners needed to know a great deal more than they already knew about the movements of traffic within cities and between cities and their suburbs:

Traffic within an urban area is more complex than on rural roads. Traffic volumes are larger, and arteries are much more numerous. Parallel streets offer many alternate routes of travel, and it is not possible to tell from observing traffic volumes alone where the drivers really want to go. Drivers often travel considerable distances out of their way to use exceptionally attractive routes, or to avoid congested or unattractive routes. Examples of this have been noted in numerous cities and origin-and-destination surveys have shown that the facts were sometimes quite different from assumptions made by engineers with long familiarity with the local situation.[4]

The old techniques that had been developed in previous years during the cooperative State-BPE traffic surveys and the statewide highway planning surveys, such as driver interviews and postcard questionnaires, were too costly, too cumbersome or not sufficiently accurate. The planners needed a better

156