also deeded to John Clarke and William Coddington in 1638 the island of Aquidneck. Miantonomo held his councils and had his fort on “Tonomy hill,” so called from an abbreviation of his name. This was the site of a small redoubt during the Revolution, and is more than a mile from Newport. In 1637 he aided in fighting the Pequots, but in 1638 he and Uncas, sachem of the Mohegans, entered into an agreement not to make war without first appealing to the English. Miantonomo was cited in 1642, upon mere rumor of intended hostilities, to appear at Boston before the governor and council. He promptly obeyed, declaring his innocence, and calling upon the English to produce his accusers. None appearing, he was dismissed with honor. “He was very deliberate in his answers,” says Hubbard, “showing a good understanding in the principles of justice and equity, as well as a seeming ingenuity withal. But though his words were smoother than oil, yet, as many conceived, in his heart were drawn swords. It was observed also that he would never speak but when some of his counsellors were present, that they might, as he said, bear witness of all his speeches at their return home.” Gov. John Winthrop, in his “Journal,” testifies to the respect in which the ability of this chief was held. The rivalry between the Mohegans and Narragansetts finally produced its natural result. Miantonomo marched against Uncas with 600 warriors, and was met by the latter with 400 men, at Great Plains, below Norwich. When Uncas saw Miantonomo's superior number, he sent a messenger to him, saying: “Let us two fight single-handed. If you kill me, my men shall be yours; if I kill you, your men shall be mine.” Miantonomo refused, and while the Narragansetts were awaiting the result of the conference Uncas fell on his face, as a signal for his warriors, who suddenly attacked the Narragansetts and put them to flight. Miantonomo, encumbered with a coat of mail that he had obtained from the English, was taken and conducted to Shantock, where he was treated with kindness, but, fearing that the Narragansetts would attempt a rescue, he was surrendered to the English at Hartford. The commissioners of the United colonies, at their meeting in Boston, referred his case to an ecclesiastical tribunal composed of five of the principal ministers of the colonies. Influenced by the representations of Uncas, they returned him to that chief for execution without torture. Uncas conducted him to the spot where he was captured, and, while he was unsuspicious of the impending danger, a brother of Uncas, at a sign from that chief, buried his hatchet in the head of their captive. Uncas cut a piece from the shoulder of the slain sachem and ate it, saying: “It is very sweet; it makes my heart strong.” Miantonomo was buried where he was slain, and the place has since been called “Sachem's plain.” In revenge the Narragansetts, led by his brother, Pessacus, invaded the Mohegan country in 1645 and drove Uncas into his fortress at Shantock. The latter was aided by the English, and the Narragansetts raised the siege and returned to their own country. It is said by some historians that Miantonomo, having called together a great number of sachems, gave them gifts and made the following speech: “We must be one as the English are, otherwise we shall all be gone shortly, for you know our fathers had plenty of deer-skins; our plains were full of deer, as also our woods, and of turkeys, and our lakes full of fish and fowl. But these English have gotten our land, they with scythes cut down the grass, and with axes fell the trees. Their cows and horses eat the grass, and

their hogs destroy our clam-banks, and we shall all be starved. Then it is best for you to do as we, for we are all the sachems from east to west,

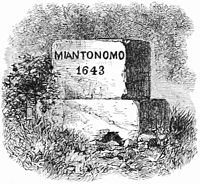

both Moquakoes and Mohawks joining with us, and we are resolved to fall upon them all at one appointed day.” The spot where Miantonomo was buried is near Greenville, on Shetucket river. A pile of stones was placed on his grave, and for many years members of his tribe came every spring to mourn there, each adding a stone to the mound. After their visits ceased, the proprietor of the land, ignorant of the sepulchre, used these stones for the foundation of a barn. In 1841 a monument was erected on the spot by the people of Greenville. It is a block of granite eight feet high and five feet square at the base, bearing an inscription, as seen in the accompanying illustration. — His son, Canonchet, was fearless, bloody, and cruel. The Narragansetts under him espoused the cause of King Philip. In 1676, having been surprised and captured, his life was offered him on condition of making peace with the English, but he spurned the proposition. When informed that he was to be put to death, he said: “I like it well. I shall die before my heart is soft, and before I have spoken a word unworthy of Canonchet.”

both Moquakoes and Mohawks joining with us, and we are resolved to fall upon them all at one appointed day.” The spot where Miantonomo was buried is near Greenville, on Shetucket river. A pile of stones was placed on his grave, and for many years members of his tribe came every spring to mourn there, each adding a stone to the mound. After their visits ceased, the proprietor of the land, ignorant of the sepulchre, used these stones for the foundation of a barn. In 1841 a monument was erected on the spot by the people of Greenville. It is a block of granite eight feet high and five feet square at the base, bearing an inscription, as seen in the accompanying illustration. — His son, Canonchet, was fearless, bloody, and cruel. The Narragansetts under him espoused the cause of King Philip. In 1676, having been surprised and captured, his life was offered him on condition of making peace with the English, but he spurned the proposition. When informed that he was to be put to death, he said: “I like it well. I shall die before my heart is soft, and before I have spoken a word unworthy of Canonchet.”

MICCONOPY, Indian chief, b. about 1786; d. in Fort Gibson, Ark., in January, 1849. He was head chief of the Seminole Indians, and commanded in person at Maj. Francis L. Dade's defeat on 28 Dec., 1835, and also with Osceola (q. v.) at the Ouithlacoochie in 1836, but was opposed to the war, and surrendered in December, 1837. His name signifies “pond king.”

MICHÆLIUS, Jonas, clergyman, b. in 1577; d. in Holland after 1638. He was educated at the University of Leyden, and was settled as a clergyman in Holland in 1612-'16, in San Salvador in 1624-'5, and in Guinea in 1626-'7. He came to New Amsterdam in 1628, and was thus the first minister of the Dutch Reformed church in this country. He organized a consistory, and administered the sacraments, but returned to Holland in a few years, probably before the arrival of his successor, Rev. Everardus Bogardus, in 1633. His wife died in New Amsterdam shortly after his arrival. The classis of Amsterdam wished to send Michælius back to this country in 1637, but he did not return. It was long supposed that Bogardus was the first Reformed church clergyman in this country, but the precedence of Michælius was established by a letter from him to Rev. Adrian Smoutius, dated New Amsterdam, 11 Aug., 1628, which was recently found in the Dutch archives at the Hague. In this letter he describes the degraded state of the natives, and proposes to educate their children without trying to redeem the parents. Michælius's letter is printed in an appendix to Mary L. Booth's “History of the City of New York” (New York, 1859).

MICHAUX, André (me-sho), French botanist, b. in Satory, near Versailles, France, 7 March,