the roof; then a vehicle was tried in which two passengers could sit face to face, but sideways as regarded the horse, as people sit in omnibuses. The Hansom cab is the last expression of civilisation.

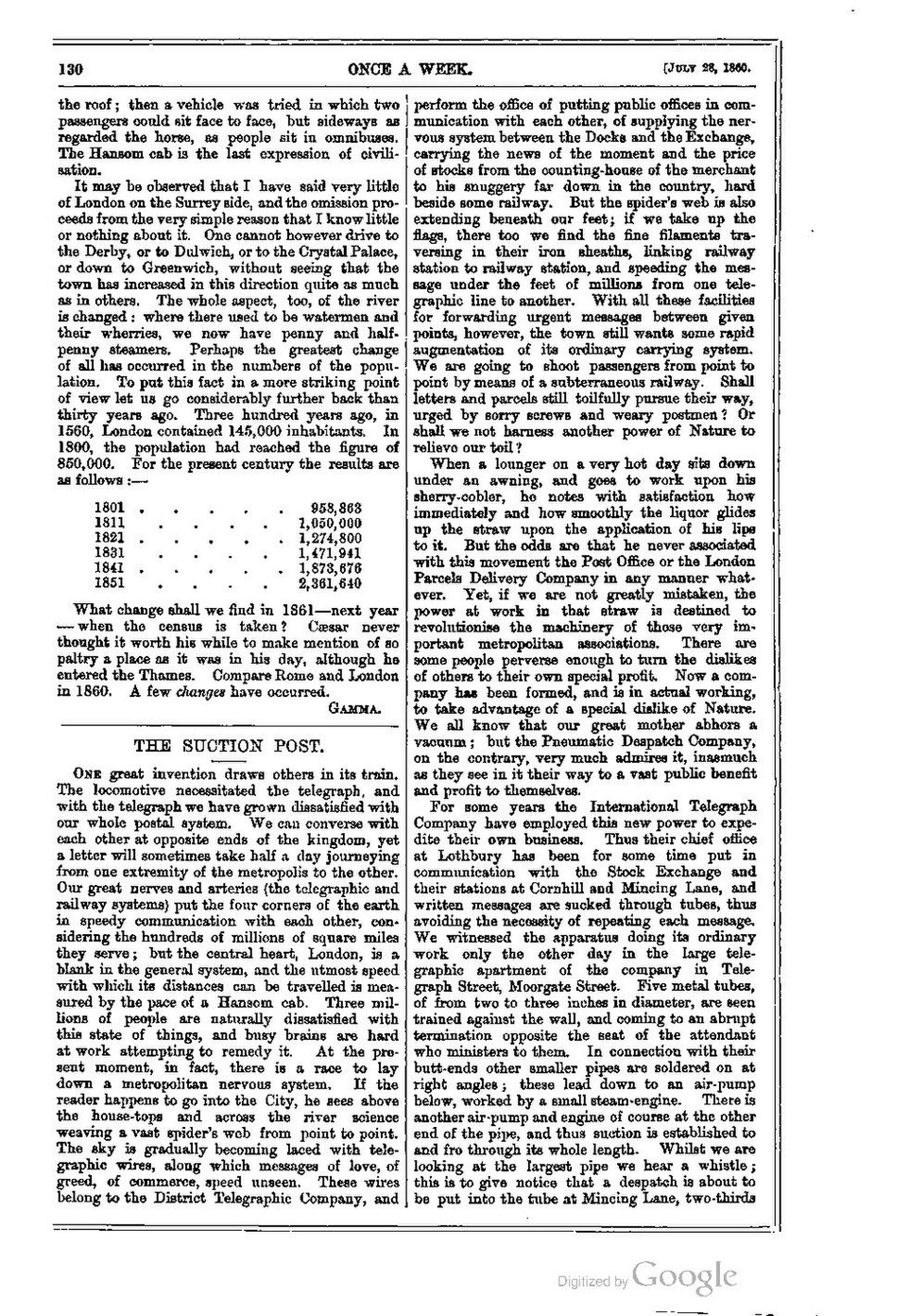

It may be observed that I have said very little of London on the Surrey side, and the omission proceeds from the very simple reason that I know little or nothing about it. One cannot however drive to the Derby, or to Dulwich, or to the Crystal Palace, or down to Greenwich, without seeing that the town has increased in this direction quite as much as in others. The whole aspect, too, of the river is changed: where there used to be watermen and their wherries, we now have penny and half-penny steamers. Perhaps the greatest change of all has occurred in the numbers of the population. To put this fact in a more striking point of view let us go considerably further back than thirty years ago. Three hundred years ago, in 1560, London contained 145,000 inhabitants. In 1800, the population had reached the figure of 850,000. For the present century the results are as follows:—

|

1801

....................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................

|

2,361,640958,863 |

|

1811

....................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................

|

1,050,000 |

|

1821

....................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................

|

1,274,800 |

|

1831

....................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................

|

1,471,941 |

|

1841

....................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................

|

1,873,676 |

|

1851

....................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................

|

2,361,640 |

What shall we find in 1861—next year—when the census is taken? Cæsar never thought it worth his while to make mention of so paltry a place as it was in his day, although he entered the Thames. Compare Rome and London in 1860. A few changes have occurred.

THE SUCTION POST.

One great invention draws others in its train. The locomotive necessitated the telegraph, and with the telegraph we have grown dissatisfied with our whole postal system. We can converse with each other at opposite ends of the kingdom, yet a letter will sometimes take half a day journeying from one extremity of the metropolis to the other. Our great nerves and arteries (the telegraphic and railway systems) put the four corners of the earth in speedy communication with each other, considering the hundreds of millions of square miles they serve; but the central heart, London, is a blank in the general system, and the utmost speed with which its distances can be travelled is measured by the pace of a Hansom cab. Three millions of people are naturally dissatisfied with this state of things, and busy brains are hard at work attempting to remedy it. At the present moment, in fact, there is a race to lay down a metropolitan nervous system. If the reader happens to go into the City, he sees above the house-tops and across the river science weaving a vast spider’s web from point to point. The sky is gradually becoming laced with telegraphic wires, along which messages of love, of greed, of commerce, speed unseen. These wires belong to the District Telegraphic Company, and perform the office of putting public offices in communication with each other, of supplying the nervous system between the Docks and the Exchange, carrying the news of the moment and the price of stocks from the counting-house of the merchant to his snuggery far down in the country, hard beside some railway. But the spider’s web is also extending beneath our feet; if we take up the flags, there too we find the fine filaments traversing in their iron sheaths, linking railway station to railway station, and speeding the message under the feet of millions from one telegraphic line to another. With all these facilities for forwarding urgent messages between given points, however, the town still wants some rapid augmentation of its ordinary carrying system. We are going to shoot passengers from point to point by means of a subterraneous railway. Shall letters and parcels still toilfully pursue their way, urged by sorry screws and weary postmen? Or shall we not harness another power of Nature to relieve our toil?

When a lounger on a very hot day sits down under an awning, and goes to work upon his sherry-cobler, he notes with satisfaction how immediately and how smoothly the liquor glides up the straw upon the application of his lips to it. But the odds are that he never associated with this movement the Post Office or the London Parcels Delivery Company in any manner whatever. Yet, if we are not greatly mistaken, the power at work in that straw is destined to revolutionise the machinery of those very important metropolitan associations. There are some people perverse enough to turn the dislikes of others to their own special profit. Now a company has been formed, and is in actual working, to take advantage of a special dislike of Nature. We all know that our great mother abhors a vacuum; but the Pneumatic Despatch Company, on the contrary, very much admires it, inasmuch as they see in it their way to a vast public benefit and profit to themselves.

For some years the International Telegraph Company have employed this new power to expedite their own business. Thus their chief office at Lothbury has been for some time put in communication with the Stock Exchange and their stations at Cornhill and Mincing Lane, and written messages are sucked through tubes, thus avoiding the necessity of repeating each message. We witnessed the apparatus doing its ordinary work only the other day in the large telegraphic apartment of the company in Telegraph Street, Moorgate Street. Five metal tubes, of from two to three inches in diameter, are seen trained against the wall, and coming to an abrupt termination opposite the seat of the attendant who ministers to them. In connection with their butt-ends other smaller pipes are soldered on at right angles; these lead down to an air-pump below, worked by a small steam-engine. There is another air-pump and engine of course at the other end of the pipe, and thus suction is established to and fro through its whole length. Whilst we are looking at the largest pipe we hear a whistle; this is to give notice that a despatch is about to be put into the tube at Mincing Lane, two-thirds